The Rio Grande Delta has many wide, shallow waterways

ringed by extensive tidal zones. Most of the archeological sites are

found on stabilized dunes and levees overlooking the marshes, bays,

and river channels. |

||

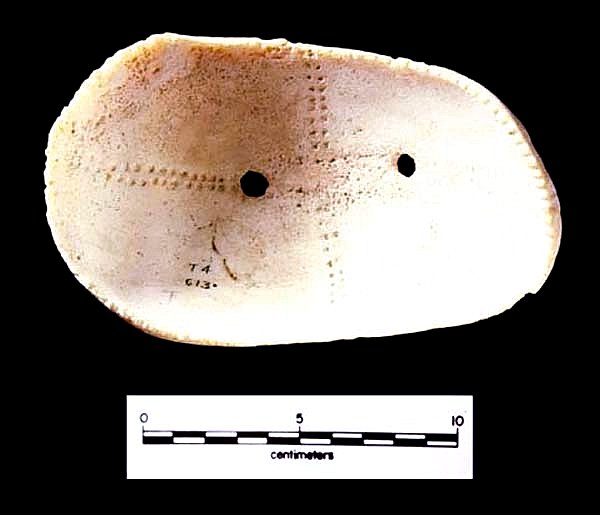

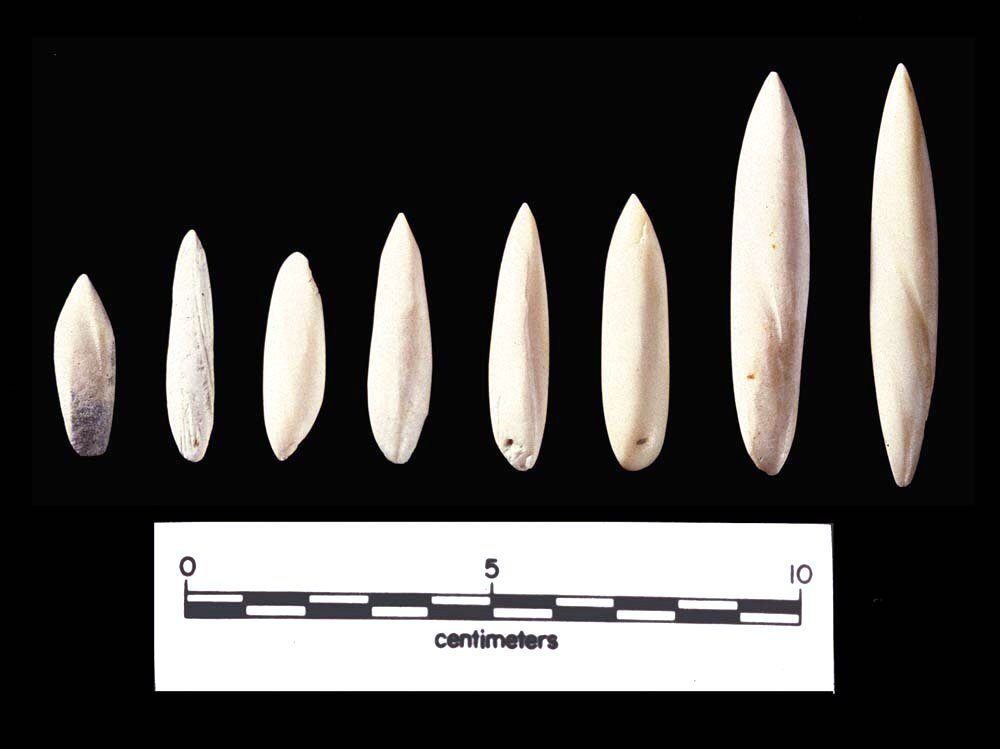

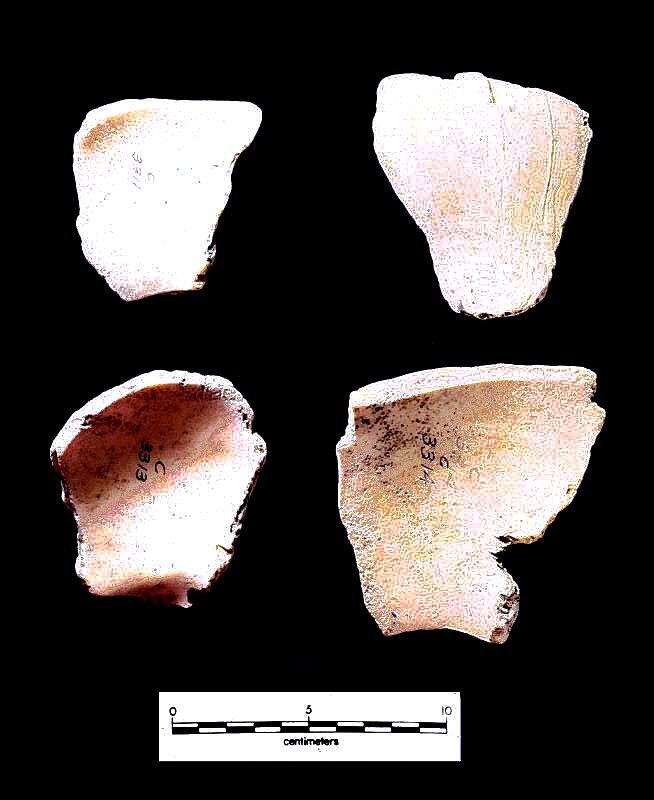

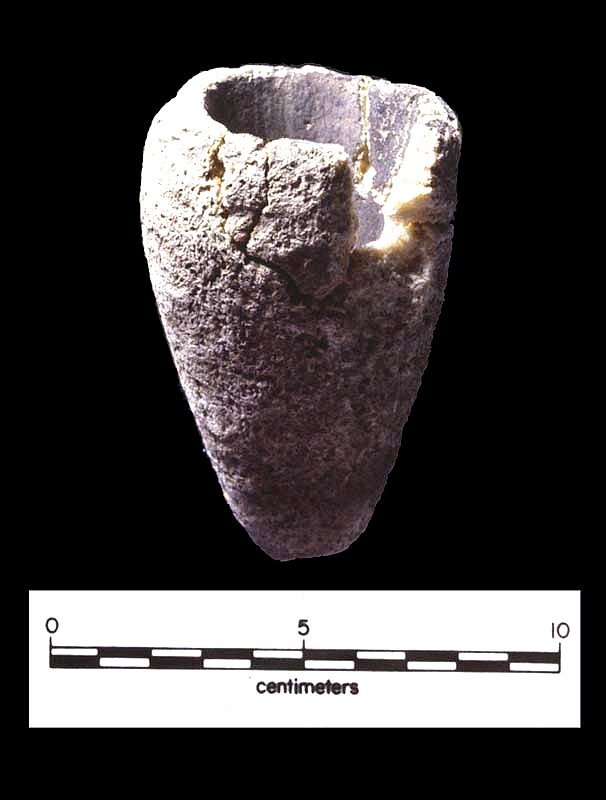

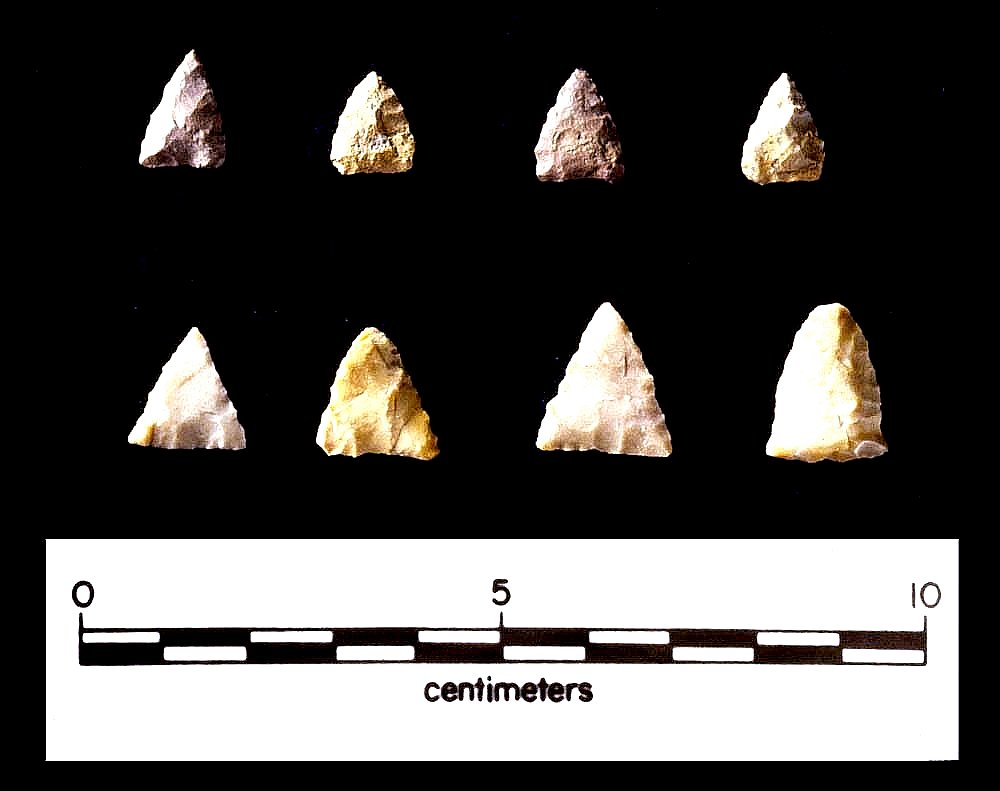

| The Brownsville-Barril complex or culture is the name that archeologists have given to the remains left by the little-known Indian groups who occupied the Rio Grande Delta at the extreme southern tip of Texas during the time period of A.D. 1100-1700. The low-lying tropical delta area was one of the last parts of northeastern Mexico to be explored and settled by the Spanish. They did not turn their attention to the Rio Grande Delta until 1747, about 150 years after they first established towns in Nuevo Leon and Coahuila. The mid-eighteenth century accounts suggest that as many as 50 named Indian groups lived in the Rio Grande Delta. Based on the archeological record of the preceding centuries, the basic lifeway seen by the Spanish when they entered the region was little different from that of the later prehistoric peoples. There is little evidence of Archaic and earlier occupations in the Rio Grande Delta probably because earlier evidence has been buried by flood deposits or destroyed by hurricanes. The peoples of the Rio Grande Delta were hunters, fishers, shellfish collectors, and plant gatherers who moved frequently as the seasons, tides, and food supplies dictated. They lived in a semi-arid, semi-tropical environment and camped on small rises along the many bays, lagoons, oxbow lakes, and estuaries. From these waterways they harvested shellfish and fish for food and seashells as raw material. The Rio Grande Delta is almost devoid of natural stone—instead it is built of mud carried down the river by floods and sand pushed up from the Gulf of Mexico by hurricanes and strong currents. Having no flint or other stone, the Brownsville-Barril people used seashells to fashion an amazing variety of shell tools and ornaments including projectile points shaped from conch shell, carved conch shell pendants, olive shell tinklers/bells, freshwater and marine shell beads, and many other tool forms. These shell artifacts were traded to more settled peoples further to the south in northeastern Mexico along the periphery of Mesoamerica, the great heartland of civilization that stretched from northern Mexico to Costa Rica. In exchange, the Brownsville-Barril peoples received exotic items including pottery, jade, and obsidian that are rarely found in Texas beyond the Rio Grand Delta. In fact this is one of the most interesting archeological questions about the area: What was the nature of trade and contact between these nomadic delta peoples and the much more sophisticated cultures to the south? The people of the Rio Grande Delta were also distinctive in the manner in which they buried their dead. Individuals were buried in tightly flexed positions, and graves were located away from living areas. The deceased was accompanied by offerings such as shell beads and pendants, animal and human bone awls, and bone beads or tubes used as jewelry. With some burials, red pigment powder was strewn over the burial. Others included Mesoamerican goods such as prehistoric pottery vessels from the Tampico, Mexico region, obsidian (volcanic glass) arrow points from sources in central Mexico, and greenstone (jadeite) jewelry, also from Mexico. Much of what is known about the Brownsville-Barril complex is due to the efforts of a civil engineer and draftsman from Brownsville, Texas. From 1917 to 1941, Andrew Eliot Anderson, took extensive notes, drafted maps, and collected distinctive artifacts from archeological sites of the Rio Grande Delta and Laguna Madre of coastal south Texas and northeastern Mexico. After World War II, the area was drastically transformed by land clearing, agricultural modification, and urban development. Today most of the sites that Anderson visited have been destroyed. The A. E. Anderson collection, now housed at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, is a crucial research resource. The Rio Grande Delta of today bears scarce resemblance to its appearance prior to the twentieth century. The great river has been reduced to a trickle by upstream dams and heavy agricultural demand. The fertile soils and mix of marsh, waterways, and raised areas have been homogenized—the smaller waterways filled in, the clay dunes flattened, and the area covered by expanses of agricultural fields, orchards, and urban areas. The majority of the archeological record has been destroyed, particularly the most fragile and most visible materials that were once common on and near the surface. The best potential for learning more about the Brownsville-Barril complex is a combination of renewed ethnohistoric research—combing the Spanish archives for eyewitness accounts of the native peoples of the Rio Grande delta—and analyses of the existing collections and notes. CreditsWilliam J. Wagner, III, prepared this exhibit as part of his thesis research at UT Austin. More recently the A. E. Anderson collection has seen new research as discussed in the TARL Blog piece linked below. Many researchers continue to be fascinated by the tool and ornament-making industry that once connected the lives of those who lived in the Rio Grande Delta to the Huastec. LinksThe A.E. Anderson Collection https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/bba11 https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Laguna_Atascosa/ Print SourcesAnderson, Andrew E. Hester, Thomas R. Hester, Thomas R., and F. J. Rueckling MacNeish, Richard S. 1958 Preliminary Archeological Investigations in the Sierra de Tamaulipas, Mexico. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 48(6). Prewitt, Elton R. Salinas, Martin Terneny, Tiffany Tanya Wagner, William J., III |

||

Texas Beyond History

Texas Beyond History

Site Map

TBH WebTeam

1 October 2001