A total of 219 engagements between

the army and the Indians in Texas can be documented;

of these, 158 can be classified into the categories

shown. Click for detail.

|

Composition of U.S. Army. Over time,

a chronic shortage of mounted troops heightened the

army's difficulties in meeting an increasing variety

of assignments. Click to enlarge.

|

Total strength of the U.S. army from

1848 to 1874. Texans never felt they had their fair

share of troop resources, although in 1856, fully 25%

of the entire army was based in Texas.

|

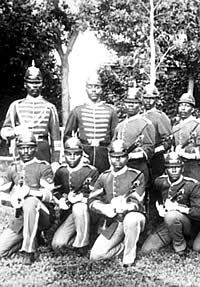

School class at Fort McKavett, Texas,

1894. (Click to see full image.) Schools, roads, churches

and jobs were among the many benefits brought by the

U.S. army to Texas. Photo courtesy Fort McKavett SHS,

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

|

Frontier forts served as bases from which scouts,

pursuits, large-scale offensives, and escorts or guards were

launched. Before the Civil War, most common was combat resulting

from a successful pursuit, triggered by information gleaned

by post or detachment commanders that Indians had been discovered.

Following the war, however, most engagements stemmed from

routine scouts, sent to interdict likely avenues of approach

or widely used trails or waterholes.

Most of the successful large-scale expeditions,

involving several companies engaged in campaigns that were

projected to take longer and involve greater distances, also

came after 1865. Combat involving mail parties, stagecoaches,

and construction teams accounted for less than 10 percent

of all engagements. The overwhelming majority of the fights

were short and badly fragmented skirmishes involving about

three dozen combatants per side. Sixty-four soldiers were

killed and 116 wounded during these clashes; the army reported

424 Indians killed, 112 wounded, and 267 taken prisoner.

Assessing the true military effectiveness of

the frontier forts in Texas is difficult. As historian Robert

Utley has noted, many officers saw the wars against the Indians

as a "fleeting bother," not worthy of the time or

energy it would take to develop tactics or strategy suitable

to such conflicts. Successful officers developed methods through

personal observation, by trial and error, by word of mouth,

or by individual ingenuity rather than through recognized

army doctrine.

The vast majority of scouts, pursuits, and large-scale

campaigns found no Indians. Pointing to the futility of such

efforts, Texans often charged that the federal government

never devoted sufficient resources to their state. Although

such claims often made for good politics with the folks back

home, in reality Texas probably exceeded its fair share of

War Department resources; in 1856, for example, fully twenty-five

percent of the entire army was based in Texas. More telling,

if less politically popular, was the argument that the army

was simply too small to carry out all the responsibilities

expected of it. In addition to fighting Indians, regulars

garrisoned coastal defensive fortifications, provided assistance

to civilians in times of crisis, helped to maintain domestic

order, patrolled national parks, conducted scientific research,

and engaged in civil engineering jobs. The chronic shortage

of mounted troops exacerbated the army's difficulties.

Despite these shortfalls, the frontier forts

had an enormous impact on Texas history. As one observer exclaimed,

army forts served "as the oasis in the desert" for

many a weary traveler. The forts also provided a tremendous

economic stimulus. From 1849 to 1900, the army disbursed some

$70 million in Texas, an amount equivalent to more than twice

the valuation of all the assessed property in the state at

the time of its annexation. And with the army often came schools,

churches, roads, and surveys.

Offering jobs, profits, a modicum of American

culture, the army's forts often served as the genesis for

permanent civilian settlement, resulting in new towns like

San Angelo, Gatesville, Fort Davis, Fort Stockton, and Fort

Worth. Their presence also boosted the chances of existing

sites like San Antonio (usually the site of department headquarters),

Eagle Pass, Brownsville, and El Paso. As a legendary Texas

historian once put it, "No story of the Texas heritage

can be complete without telling the role its forts played

in making that heritage possible."

|

Cavalry Charge on the Plains. In

Texas, most of the successful large-scale expeditions

came after 1865. Painting by Frederick Remington, courtesy

Amon Carter Museum. Click to enlarge.

|

A stagecoach mired in the mud, on

mail route east of Fort Stockton, March 12, 1885. Escort

duty was a critical assignment for frontier troops.

Photo courtesy Fort Concho NHL. Click to enlarge.

|

An army encampment near Santa Rosa

Springs, circa 1884. Courtesy Fort Concho NHL. Click

to see full image.

|

|

No story of the Texas heritage can be complete without

telling the role its forts played in making that heritage

possible.

|

Families disembark their wagons for

a welcome rest at Fort Concho. As one observer has noted,

army forts served "as the oasis in the desert"

for many a weary traveler. Courtesy Fort Concho NHL.

|

|