Attempts at Native Conversions along the Rio Grande |

Buzzards swirl above the ruins of the San

Bernardo Mission church, the only structure remaining of the "Gateway" mission and presidio complex in Guerrero, Mexico.

Begun in 1760 using local travertine stone, the church —in its second location at the Rio Grande site—was never completed. Photo by

Bobby Inman. |

|

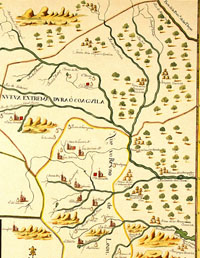

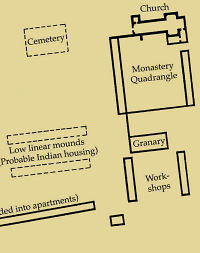

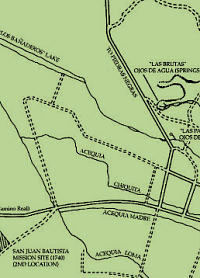

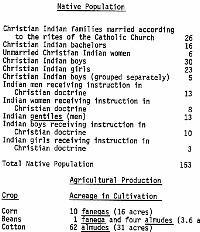

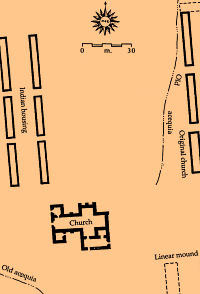

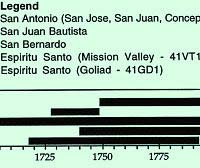

The year was 1699 and a Spanish force, including Franciscan monks from Queretero in central Mexico, moved north to Monclova, Coahuila intent on settling land claimed by Spain and bringing the Christian religion to the native peoples they encountered. Precious metals were also part of the Spanish quest, as was finding a labor force to work the mines and mission fields. The mission the Franciscans founded at Monclova (about 120 miles southwest of Laredo) was not successful and was closed. The 1699 move would push the frontier northward to the Rio Grande and beyond. They established the new northern gateway at a well-watered locality where today lies the small village of Guerrero, Coahuila, about 30 miles south of Eagle Pass, Texas. The surrounding area on both sides of the Rio Grande had been occupied by small, mobile groups of hunters and gatherers for a least 13,000 years. This part of northeastern Mexico has a very dry climate, lying in the rain shadow (rain-poor, leeward side) of the rugged Sierra Madre Oriental mountains. In the past, freshwater springs, termed ojos de agua, emanated near present day Guerrero, creating an oasis in the desert-like lands of northern Coahuila. The springs carried a high charge of travertine in solution and these deposits formed a natural dam sometime in the ancient past, creating a large lake (laguna) and a smaller lake behind it. Several fords (pasos) across the nearby Rio Grande made this locality particularly attractive to the Spanish. These fords undoubtedly had been used as traditional river crossing points throughout prehistoric times. They were to become critical to Spanish efforts in settling and supplying the frontier. By 1700, construction of buildings was underway. Soon, three missions and a presidio had been established: San Juan Bautista (January, 1700), San Francisco Solano (March, 1700), and San Bernardo (1702). The missions were situated in a triangular pattern around the important springs and lakes. Initially, a mobile cavalry unit was assigned to protect the missions, later a permanent garrison, Presidio San Juan Bautista, was erected. This complex, symbolizing military and religious might, was a key installation for the Spanish as they settled the northern frontier of New Spain. The town of Guerrero, its missions, and fortress, were to become the "Gateway to Spanish Texas." Investigations at the MissionsThe Gateway missions were the focus of a two-year study undertaken in the 1970s by the Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). Led by project director R. E. W. Adams and archeologists Jack Eaton, and Thomas R. Hester, the Gateway Project conducted excavations, historical research, and ethnohistoric studies of Indian groups concentrated in the missions of San Bernardo and San Juan Bautista. Work at San Bernardo uncovered the original surface of the mission quadrangle, workshops and living quarters of the priests, and foundations of six long structures built to house native peoples and arranged in rows along a street, termed “calle de los indios.” According to records, the buildings were made of adobe with travertine footings. At the San Juan Bautista site, the church, priest’s quarters, workshops, and Indian housing were excavated. At both sites, chipped stone tools, ceramic sherds, and animal bone were recovered. Historians, including Felix Almaraz of UTSA and T. N. Campbell of the University of Texas at Austin, culled Spanish records for insights into the mission population and how the traditional hunter-gatherers adapted to a sedentary, agrarian way of life. The names of nearly 90 Native American groups from northeastern Mexico and southern Texas were identified in mission census lists and other accounts. Campbell’s data, compiled from ecclesiastical, military, and personal accounts, enabled him to link the Pacuache, one of the native groups living at San Bernardo in 1775, to their former homeland range in Dimmit and Zavala counties and possibly to the Tortuga Flat (learn more) archeological site, radiocarbon dated to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The following sections provide a brief overview of the Indians connected to the missions along with examples of the items they left behind, many indicating their reluctance to abandon traditional lifeways. Mission Indians in their New LifeDuring the early 1700s, the native hunter-gatherers from northern Mexico and southern Texas were brought into the missions along with other Indian groups who were recent immigrants into the area. To the northwest, upon and beyond the Edwards Plateau, many small groups already had been displaced by aggressive mounted raiders, the Comanche and Apache peoples. The stone walls of the missions, guarded by Spanish soldiers from the presidio, appeared to offer refuge. Many of the native groups of the region were described by the Spanish as aggressive, belligerent, nomadic, and in need of indoctrination. The native groups of northeastern Mexico (and adjacent Southern Texas) are often labeled as "Coahuiltecans," a term that can be applied properly only as a geographical term, rather than as an ethnic classification. It was once believed that most of the small native groups of the region all spoke dialects of the same language-Coahuilteco. Later work revealed the extent of the native people's linguistic and ethnic diversity. Among the aboriginal languages spoken in the region were: Coahuilteco, Comecrudo, Cotoname, Solano, Karankawa, Aranama and Sanan. At least six different languages were found among the groups who came to the Rio Grande missions. Spanish mission documents record what at first glance appears to be a success story. According to the historian Espinosa, a typical day was framed morning and evening with prayers which the natives learned to recite in Castillian. In addition to instruction in religion, the Indians were taught to plow fields, grow crops and fruit trees, maintain herds of domestic animals, and weave cotton and wool into cloth. Several boys were organized into an a capella choir. Baptisms of native children were special events following long periods of instruction by the friars. Carefully groomed and dressed, the young Indians lined up to be assigned godparents, couples from the presido, as well as given Christian names. Census records from the late 1700s ennumerate the Spanish Christian names of members of native familes along with names of their tribal groups—Mescal, Pacoa, Pampopa, Pacuache, Canoa, Payaya, Aguayan, among others —in a curious blending of western and indigenous traditions. At times, there were as many as 300 Indians counted in the mission census with baptisms taking place periodically. Such good reports were important to the friars and other interested Spanish officials as they insured more funding of the missions on the northern frontier. |

|

|

|

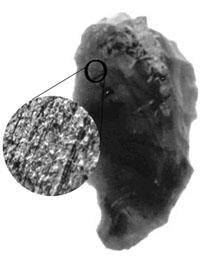

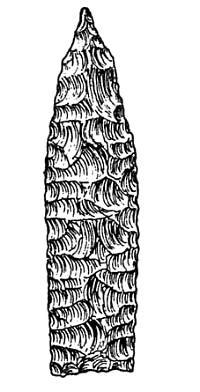

The stone tool assemblages from the Gateway missions are marked by the appearance of a new style of arrow point - the Guerrero point. This distinctive, stemless, triangular arrow point has been found in most mission settings across Texas. Although this is the earliest known occurrence of this new arrow point style, it is unclear whether it originated at the Gateway missions. The contexts in which it was found-in and around the mission compound (the Indian housing area and middens) and the extended occupation periods (San Bernardo and San Juan Bautista were not secularized until 1794)-make it difficult to precisely date the introduction of the new point style. Some archeologists see the Guerrero style arrow point as a continuation of the long prehistoric tradition of making unstemmed projectile points in south Texas and northeastern Mexico. The persistence of this tradition for over 5,000 years has been attributed to the region's lithic resources, which were of a generally uneven quality and could be found only in some areas (Learn More). Sources such as the Rio Grande gravels typically yield small chert cobbles from which it was easier to fashion unstemmed dart points than notched and elaborately shaped styles, although versions of the latter clearly were made and used in the region. The native peoples living in the missions may have continued the long tradition of making unstemmed points and created their own version suitable for bow and arrow weaponry. The extensive trade network among the native groups in the Spanish missions suggests that Guerrero points may have been traded along with other goods. Early records show decorated bison and cow hides were being traded among the Gateway missions and other missions in Texas. Perhaps this new point type resulted from a changed subsistence which now included domesticated animals brought by the Spanish or perhaps it was a means to show solidarity of the diverse cultural groups whose land had been invaded by the foreigners. Curtis Tunnell, in his study of Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz on the Edwards Plateau, suggests that the Guerrero point may have been introduced by the Lipan Apache as they spread southward. Very late sites on the Plains bear examples of similar triangular arrow point styles. On the other hand, as Hester pointed out in his preliminary analysis of the Gateway lithic artifacts, the Apache in south Texas were frequently hostile to the mission enclaves, not part of it. Regardless of the mechanism behind it, the spread of the Guerrero point type among such disparate groups over such a short period of time is remarkable. Decline of the Gateway MissionsMissions San Bernardo and San Juan Bautista continued in operation for more than 120 years, making them two of the oldest and most successful missions. The third Gateway mission, San Solana, was short-lived at the site; it's staff was relocated two decades after its establishment, moving on to a much more heralded future. In April, 1718, Don Martin de Alarcon and Padre Fray Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares traveled northward to establish another mission settlement which would grow into the city of San Antonio. Thus San Solana became Mission Valero (the Alamo), the first of the chain of five missions that would ultimately be founded along the San Antonio River. The two remaining Gateway missions played a significant role in sustaining the new San Antonio missions, enabling the flow of supplies to them and advancing settlement of the northern frontier. Over the decades, however, as new missions were instituted in other areas, there were calls to secularize the Rio Grande complex. The old missions hung on, however, as others failed. Finally it was determined that progress in converting the Indians to Christianity was "imperceptible." In 1781 Missions San Bernardo and San Juan Bautista were transferred to the missionary college of Pachuca. San Bernardo's Indian population had declined to 103, San Juan Bautista's to 169. Official orders of secularization were issued in 1794, although both missions continued to work with the Indians. By 1829, mission lands had been divided and alloted to settlers. A visit to the area today, near the small village of Guerrero (approximately 30 miles southeast of Eagle Pass, Texas), finds the standing remains of the Church at San Bernardo. The structure was partially restored by the Mexican government in the 1970's. While the springs are still present, the large lake so vital to the mission complex no longer exists, due to the dynamiting of the dam in the early 20th century. Credits and SourcesThe Gateway Missions exhibit was contributed by Betty Inman, with additional writing by TBH editor Susan Dial. Inman holds a Masters in Anthropology degree from the University of Texas at Austin. She has worked on a variety of early historic and mission sites in south Texas including Mission Espiritu Santo at Victoria (41VT11) and Fort St. Louis and as a staff member for the LCRA's Nightengale Archeological Center in Kingsland. Her current interests include reconstruction of Caddo ceramics for Archeological and Environmental Consultants. UT-Austin Professor Emeritus Thomas R. Hester, who worked on the Gateway project, consulted in the creation of this exhibit. |

|

Print SourcesAdams, R. E. W. Almaraz, Felix D., Jr. 1979 Crossroads of Empire: The Church and State on the Rio Grande Frontier of Coahuila and Texas, 1700-1821. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio. Campbell, T. N. 1979 Ethnohistoric Notes on Indian Groups Associated with Three Spanish Missions at Guerrero, Coahuila. Special Report No. 3. Center for Archaeological Research, the University of Texas at San Antonio. Eaton, Jack Hester, Thomas R. 1977 The Lithic Technology of Mission Indians in Texas and Northeastern Mexico. Lithic Technology 6(1-2):9-13. Inman, Betty Ricklis, Robert A. Turner, Ellen Sue and Thomas R. Hester Weddle, Robert S. |