Chaparrosa Ranch

The first archeological field school by the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) was held in June and July 1974 at the Chaparrosa Ranch in Zavalla County. The field school director was an assistant professor who was younger than all but one of the students enrolled in the course, among whom were four retired Air Force colonels. Headquarters were established at a hunter’s cabin, watered by a well and with an air-conditioned dining area. One of the colonels plugged in his spacious travel home, while other students put up tents under mesquite trees that provided some shade for at least a portion of the day. Carefully-crafted, handmade, fortress-level latrines stood in the middle of a clearing downwind. The climate was typically hot and humid, and as also predictable in June, broken by a ferocious seven-inch rainstorm.

The camp had a number of characters, visitors, and memorable moments. T. C. Hill, Jr. of Crystal City brought his guitar and thick compilation of Mexican canciones and sang well into the morning hours. A very aggressive bull “penned up” several latrine occupants for quite a while, and on another visit, ran one of the colonels up a nearby windmill. One night, two unexpected visitors arrived late, on foot and very drunk. After drinking from one of the camp’s water faucets for a good while, they collapsed on the ground near the cabin, sound asleep. These lost and exhausted wanderers had no idea that their presence in the camp that night had been monitored in the shadows by Col. Tom Kelly, holding a loaded pistol. The next morning, when our visitors came to, the students fed them and sent them on their way, with enhanced provisions and better funding, courtesy of that same colonel who had followed their every move the night before.

All field schools have their stories and a mythology that grows over the years that follow. And even though the field school members and their guests celebrated the 4th of July with one too many vodka-filled watermelons, some memories will always be clear. What is lost in many field school stories is just how hard the students worked, sweated, and endured--whether or not the field school taught them much “archaeology,”--or if the six-week exercise led to new data relating to defined research problems. The students of the 1974 UTSA field school succeeded admirably in their tasks, and their work certainly added to the director’s research goals formulated four years earlier.

The Chaparrosa Archaeological Project

Chaparrosa Ranch covers 70,000 acres of Zavala County, in the southwestern part of the South Texas Plains. Drained by two major, parallel tributaries of the Nueces River – Turkey Creek and Chaparrosa Creek-- a broad valley has been created along a north-south axis. The two creeks have cut many channels across the valley, creating a braided pattern of drainages and isolating several landforms. The valley walls on the west and east are well defined and capped by outcrops of Uvalde gravels, a source of cherts used in ancient stone-tool making in the region. The streams are lined with heavily vegetated riparian zones and the floodplains support a variety of plants that were exploited as food resources. The combination of vegetation zones, scattered specialized ecological niches, and the presence of sustained water sources have also created conditions for abundant wildlife. The natural resources, enhanced by documents on the area, its resources, and its native peoples ranging from the 18th century through the early 20th century, have provided an excellent “laboratory” for examining the Native American settlement of a contiguous environment encompassing more than 40 square miles.

In August, 1969, Wayne T. Hamilton, then the business manager for the Ranch (now Professor of Range Science at Texas A&M University) made arrangements for an initial visit to the ranch, owned at that time by the late Belton Kleberg Johnson. Accompanied by T. C. Hill, Jr., and with the encouragement of the late Jack Youngblood (foreman), we drove to several parts of the ranch, looking at and recording several sites. It was soon clear that there were some buried sites on the ranch, and that the Chaparrosa and Turkey Creeks had formed a distinctive valley, and that numerous resources had existed – from chert outcrops on the edges of the valley to the water and vegetation of the stream courses—that would have favored repeated prehistoric occupations.

Recognizing these opportunities, the Chaparrosa Archaeological Project was initiated by a survey and testing program in 1970, supported by a grant from the University of California, Berkeley, and equipment and a vehicle from Texas State Archeologist Curtis Tunnell and TARL Director, Dee Ann Story. This work was followed by UTSA field schools in 1974 and 1975, and intermittent survey activities through the early 1980s. The archeological investigations resulted in major excavations at two sites, testing and controlled collecting at many others, and the use of systematic survey techniques to document more than 250 other sites on all landforms. The data from Chaparrosa Ranch were used for initial studies of settlement systems and in the development of research plans for fieldwork in the region.

The terrain has the typical vegetation of the South Texas Plains, with mesquite and all of its thorn-bearing associates, prickly pear cactus and tasajillo, cenizo, guajillo, and blackbrush, granjeno, and whitebrush, and a myriad of other plants that contribute to the special smells of the area. Two major streams run through the ranch, from north to south. The deeper, more densely vegetated is the Chaparrosa Creek, with deep pools in some areas and dry channels in others. Flowing springs once issued forth from a major sandstone outcrop on the north part of the ranch. Paralleling the Chaparossa Creek, in its own valley and separated by the “divide” between the two streams, is Turkey Creek. It is a less impressive waterway, muddy, with the riparian forest being more brush than anything else. In aerial photos, its braided channels are clear, indicating the shifts of the primary channel over the millennia. Below the confluence of the two creeks, Turkey Creek drains south toward Crystal City, ending in a vast swampland often called “Comanche Lake,” a Anglicized rendition of what the 18th century Spanish (who were sometimes lost in the thick brush there) called “the Caramanchel” (the name probably derived from a village near Madrid). Spanish expeditions that crossed Chaparrosa and Turkey Creeks in the late 17th and into the 18th centuries gave various names to Chaparrosa Creek, including “Rio de San Isidro Labrador,” “Arroyo San Luca.,” According to Father Massanet in 1691, the creek was called “Guanapacti” by local Indian groups. It is not known whether this was the landscape name used by the Pacuache Indians, likely the resident historic group in the Chaparrosa area, or that of another group.

Research Goals and Attempts to Implement Them

Beginning with the 1970 survey and testing program, the Chaparrosa Archeological Project had two stated goals:

- 1. to record and sample sites in varied topographical and ecological locales – to help reconstruct, on a preliminary basis, the prehistoric settlement-subsistence systems;

- 2. to locate and test sites with buried deposits, hoping to find those with sufficient depth to warrant larger excavations, and which would hopefully help toward establishing a sound cultural sequence.

I (Tom Hester) felt that chronology (Goal 2) was especially important, if the settlement- subsistence system study (Goal 1) was to be meaningful in studying regional prehistory.

These objectives, and the techniques used to implement them, reflected the archaeology of the early 1970s, at least in the mind of a Berkeley graduate student! Loosely derived from “systems theory,” the research sought to link settlement patterns (distribution of sites during known periods of time) with evidence of subsistence strategies (what people ate and how they exploited food resources). Very generally put, the goal was to conjoin data on the distribution and types of sites with data that would inform us on subsistence, seasonality, and paleoenvironment. Having been trained initially as a Texas archeologist, I felt that such patterns and interpretations needed to be grounded with a solid cultural chronology, else such patterns would be a mish-mash of archaeological evidence from various time periods.

The techniques or strategies used to pursue these concerns in the Chaparrosa Ranch region included:

Site recording, some based on surveys of “high probability” areas, and to areas known to ranch personnel -- but with the use of east-west transects across the stream valley so that temporary, task-specific, or other types of habitation sites might be discovered. Because Chaparrosa Ranch was an efficiently organized place, there were ranch roads and transmission lines nicely spaced, east-west, to facilitate these transects.

Site sampling involved surface collection and, at select sites, test excavations. The Mariposa site, 41ZV83 (below, the “41” prefix will be dropped for all site numbers), had been tested in 1970, and so in the 1974, it became the first site to be excavated using an “open-area” or block approach. Surface collecting approaches were varied: some were “grab” or opportunistic sampling of diagnostics and other materials judged to be interpretative value; controlled collecting using grid systems, and even a site or two with the then-famous Binfordian “dog leash technique” (in reference to archeologist Lewis Binford).

Site excavation was carried out in hopes of chronological data, subsistence data (faunal remains, for example), paleoenvironmental samples (pollen columns), and hoped-for intrasite patterning of hearths and other features that might provide insights as to how site space was used. Open-area, or blocks of adjacent units, excavations were used, standardized ¼” screening, and selected 1/8” and water screening.

Unfortunately, faunal remains were very poorly preserved and pollen samples yielded no environmental data. Efforts to carefully collect charcoal for radiocarbon dating was very difficult: very little survived and often in associations not worth dating.

Some of the Results

A brief summary of the data from Chaparrosa Ranch gives a good idea of what the research accomplished. A number of publications exist that document much of the work, especially the excavations at the Mariposa site (ZV83). Texas Tech graduate student John Montgomery reported that site for his Master’s thesis, which was subsequently published by UTSA. The archives and collections of the Chaparrosa Archaeological Project are housed at the Center for Archaeological Research at UTSA. These include numerous, unpublished graduate student papers, a draft of part of an unfinished dissertation, field notes, photographs, and other records. While much analysis has been accomplished, an overall presentation and synthesis of the Chaparrosa Archaeological Project remains to be done.

A total of 167 sites were formally recorded on Chaparrosa Ranch, ranging in age from Late Paleoindian to Late Prehistoric. Based on the nature of the archaeological materials at these various sites and a study of their topographic and environmental contexts, a series of site definitions were set forth. Major site categories include:

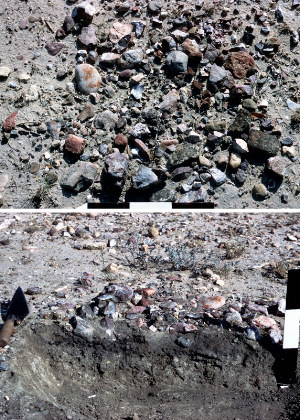

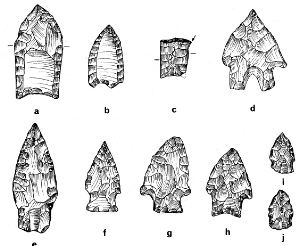

Streamside Villages: These are common along Chaparrosa and Turkey Creeks, often atop (and buried in) long, low natural levees paralleling the stream channels. Gullies cutting through them, draining into the creeks, expose burned rock (sandstone, chert), flakes, mussel shell fragments, and large numbers of Rabdotus land snails. At such sites where there is less vegetation, sheet erosion also exposes cultural remains. Two such sites have been excavated at Chaparrosa Ranch: Mariposa and ZV10. Both were deposits about 1.40 meters deep, with dark gray-brown midden-stained alluvium, overlying tan clays. At site Mariposa, small hearths and scattered hearth stones were in the upper 45 cm (midden soils), along with Perdiz, Scallorn, and Zavala points; all excavated materials were plotted in place as detailed in John Montgomery’s 1975 monograph. Radiocarbon dates range from 1400 to 400 years ago.

At ZV10, on Turkey Creek downstream from the Mariposa site, the upper alluvial clay-loam is midden-stained, with pale brown clays below. After the site was probed with four test pits in 1974, it was excavated in 1975 with a block of nine 2-meter squares. Most of the cultural material was concentrated from 14-45 cm, including a dozen concentrations of fire-cracked sandstone (hearths), a charcoal-baked clay concentration, and two other baked clay clusters.

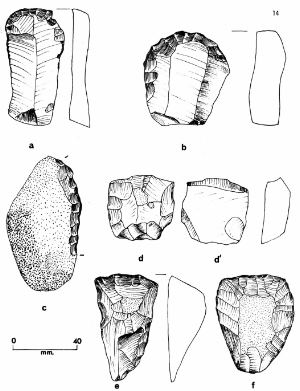

In a closer look at vertical distribution of artifacts, the Late Prehistoric (Perdiz, Scallorn, Zavala) occurs from surface to 30 cm. Just below, where the hearths were concentrated, were Ensor, Zavala, and Montell points. And toward the bottom of the excavations. between 45-75 cm, fire cracked rock was less frequent, and diagnostics included a Marcos point and two examples of the heat-treated “Shumla” form found widely in this section of the South Texas Plains. There were also cores, biface fragments, a large bifacial perforator, and a section of large antler tine. Faunal remains were recovered, although in small numbers and mostly from the Late Prehistoric; much of the recovery was through water-screening. All of the identified fauna is likely not all archaeological. The site had rodent burrowing and vertisol cracks which could have introduced some species. Briefly, the fauna included frogs, turtle, snakes (7 species), lizard, alligator gar, raccoon, ringtail, skunk, rats, mice, rabbits, whitetail deer and pronghorn antelope.

Lithic Procurement Sites: The edges of the valley are topped with outcrops of "Uvalde" Gravels, as are some upland remnants isolated by erosion near the floodplain. (See "Uvalde" Gravels West.) At the lithic procurement sites, the ancient gravel deposits are heavily concentrated, with abundant flake debris, occasional cores, “tested” cobbles (one or two flakes removed), brown-purple quartzite hammerstones, and, rarely, lithic diagnostics. The exposed occupation sites on the edge and top of the valley walls often have Paleoindian and Early Archaic artifacts, including Angostura, Golondrina, and bifacial Clear Fork tools.

Upland Sites: The uplands east and west of the creek valley are marked by red sand and broad stands of grass (much of this due to thorn-brush removal programs in the 1960s). There are no water sources, and the sites are small, with meager cultural remains. At ZV90, there was a hearth with several flakes and a core-chopper around it; site ZV89 was very similar. These are thought to be temporary, function-specific sites, such as hunting and/or gathering camps used briefly by a small group. Because of the sand and grass in much of the uplands, sites have to be located via transects, usually along east-west ranch roads that are somewhat eroded.

In addition to these kinds of sites, survey crews recorded a variety of features partially exposed on eroded surfaces or in gullies. These included a cache of manos (41ZV66), a pit filled with ashes, charcoal and baked clay lumps (41ZV82), and a number of sites with distinct chipping areas.

Roadrunner “snail kill” localities are found on Chaparrosa Ranch and across the South Texas Plains. The roadrunner uses an appropriate exposed stone cobble and brings Rabdotus snails and smashes them on the “anvil.” A litter of broken Rabdotus shell will be found over an area 1-2 meters in diameter. Such concentrations may be mistaken for archeological sites, but the latter always contain many whole shells.

Chronological Indicators

Excavated sites yielded artifacts from the Late Prehistoric into the Late Archaic. These and other artifacts were recovered during surveys and controlled collecting at many Chaparrosa sites. And some artifacts were shown us by Hamilton and Soil Conservation Service personnel, collected in the years prior to the survey. Clovis and Folsom points have been found on the ranch, or on property immediately adjacent. More common are Angostura, Golondrina, and St. Mary’s Hall, and at two sites near the valley wall east of Turkey Creek, Golondrina points and a Clear Fork biface (ZV433 and ZV436). Archaic point types are common, with considerable numbers of stemmed points typical of the northern part of the South Texas Plains, including Andice, Martindale, Langtry, Pedernales, Frio and Ensor. Still, unstemmed triangular points dominated: Abasolo, Catan, Tortugas, Matamoras, Kinney, Desmuke, and the basal-notched Carrizo. Late Prehistoric types include Perdiz, Scallorn, and Zavala. Interestingly, few indicators of the Toyah Horizon are present at Chaparrosa Ranch, and no bone-tempered pottery has yet been found. In this regard, the Late Prehistoric assemblage is very similar to the “Mission Indian” tool kit of the Gateway missions to the west.

Conclusions

The archeological research at Chaparrosa Ranch in 1974 and 1975 provided data on settlement types and distributions that was based on a systematically-designed survey, which included transects across the valley, rather than “big” site recording that has been standard practice in the region up to that time. Our excavations demonstrated that Late Prehistoric and Late Archaic sites are to be found on the natural levees paralleling the creeks – at least in those areas that we dug. At both ZV83 and ZV10, deep gully erosions in other parts of the site revealed Middle Archaic points. Test pits indicated little promise for excavation, and it may be that the Middle Archaic materials are eroded and redeposited from early floods in this drainage system. Whatever the reason, we were unable to locate any sites that looked promising for deeper excavations. There was a hint of “horizontal stratigraphy,” with Golondrina, Clear Fork bifaces, as well as Early Archaic dart points found eroded on the east edge of the Turkey Creek drainage, quite distinct from the streamside villages to the west.

We met some of our goals and others proved unachievable. The faunal record at

ZV10 is a lengthy list, but the collection is small and much of it potentially introduced by natural processes. Charcoal from the hearths at ZV10 and ZV83 provided some

assays that seem to fit the archaeology of the site, but we had too few samples. Palynological research of the 1970s did not yield pollen data; soil samples are still curated at CAR-UTSA that might be processed by more recent techniques.

Regional surveys on the South Texas Plains, on the scale of the Chaparrosa project,

have been done only occasionally during the past 30 years. Unfortunately, none have been properly finished and reported, including Chaparrosa. Such undertaking are difficult to accomplish without major funding. Fully completed, systematic regional surveys, are very worthy research projects that we badly need to improve our understandings of the prehistory of the South Texas Plains.

Contributed by Dr. Thomas R. Hester, professor emeritus, University of Texas at Austin, and former director of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at UT Austin and of the Center for Archaeological Research at UTSA, where he was a professor for 15 years and taught many field schools including those at Chaparrosa Ranch. Today Hester is “retired” and lives on the upper Seco Creek, from whence he regularly ventures forth southward into the South Texas Plains, his archeological and familial home. Hester grew up in Carrizo Springs, not far south of the Chaparrosa Ranch.

Sources

Hester, Thomas R.

1975 Late Prehistoric Cultural Patterns Along the Lower Rio Grande of Texas. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 46:107-126.

1978 Background to the Archaeology of Chaparrosa Ranch, Southern Texas.Special Report 6, Vol. 1. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

1977 Late Pleistocene Aboriginal Adaptations in Texas. Papers on Paleo-Indian Archaeology in Texas: 1, pp. 1-14. Special Report 3, Center for Archaeological Research, University of the University of Texas at San Antonio.

1984 Paleo-Indian Artifacts from Chaparrosa Ranch, Southern Texas. La Tierra 14(3):2-4.

2005 An Overview of the Late Archaic in South Texas. In: The Late Archaic Across the Borderlands: From Foraging to Farming, edited by Bradley J. Vierra, pp. 259-278. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Lovett, Bobbie

2002 Sections of manuscript draft written as part of a potential dissertation. On file, Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

Montgomery, John L.

1978 The Mariposa Site: A Late Prehistoric Site on the Rio Grande Plain of Texas. Special Report 6, Vol. 2. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio