Carvajal Crossing and El Fuerte del Cibolo

Through time, travelers sought the safest and simplest ways to cross rivers and streams. Trails leading over some of the more heavily used crossings eventually became roads and were described in journals and denoted on maps. Some crossings took on particular strategic importance.

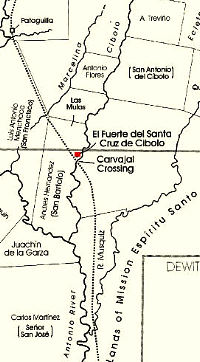

One such site, Carvajal Crossing, was located at a natural rock-lined ford of Cibolo Creek. Likely a crossing for native peoples—its use perhaps extending into the prehistoric past—it gained prominence with the coming of Spanish missionaries, soldiers, and government officials. Situated midway on the road between the villa of San Antonio de Bexar and the presidio of La Bahia in present Goliad, the crossing was a critical waypoint for travelers during the 18th century. The area, rich in rolling grasslands, was home to several Spanish ranchos—arguably, it was here that ranching in America got its start. Many of the ranchos supported large herds of cattle for the missions. But raids on herds and homes by Apaches were a constant threat for these early settlers.

To strengthen defenses and provide more security for these vital enterprises, Governor Manuel de Sandoval ordered more soldiers to the presidio in San Antonio. And to protect their horses from the Indian raiders, he positioned the herds at the remote site on the Cibolo. A small outpost, or fort, was erected at the site in 1734 and a small garrison of soldiers posted there. Called El Fuerte de Santa Cruz del Cibolo , or El Fuerte del Cibolo, the small fort likely consisted of nothing more substantial than jacales, structures made of mud and sticks, and a few dugouts. It existed only three years, however, before it had to be abandoned, following two raids in which more than 400 horses were stolen. The remaining herds and soldiers were moved back to San Antonio.

In spite of the Indian threat, travel increased on the mission road, and more ranches were established, including the first privately owned ranch in Texas, that of Andres Hernandez, in the vicinity of the outpost. In 1771, following a series of readjustments in Spanish Colonial policy to increase frontier protection, the fort was re-established on the Cibolo. This time, the fort was built with a wooden stockade in which ranchers could seek shelter. For roughly 10 years, the soldiers helped protect area ranches as well as the mail route between Presidio la Bahia and San Antonio de Bexar. By 1782, however, hostilities with the Comanche increased to the point that the fort was once again closed; this time the buildings were burned to prevent their use by Indians. Some ranches also were abandoned, leaving only 6 or 7 still operating and less than 100 Spanish settlers in the area.

In 1838, the land encompassing the crossing and fort site was given to Jose Luis de Carvajal by his aunt, Barbara Sanchez, who had inherited the tract in the Hernandez grant. Caraval, a descendant of a Canary Islander family, reportedly built a dugout structure, covered with green saplings, near the crossing. He and his wife, Maria de Jesus Flores, raised nine children on the ranch. During that time, they maintained a peaceful co-existance with a group of Lipan Apache reportedly living in a village across the river. Ultimately, the Carvajals and Lipans were both driven away by the Comanche.

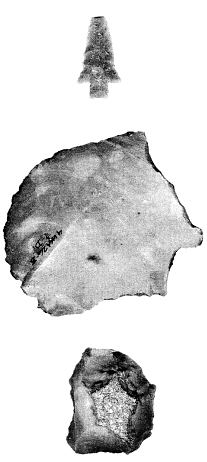

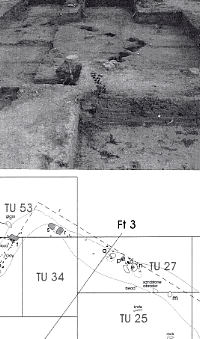

In 1985, in advance of a bridge-widening project on FM887 near the crossing, archeologists from the Texas Department of Transportation conducted test excavations at the site thought to encompass the location of the Spanish Colonial fort. They uncovered more than 4000 artifacts, including sherds of Spanish Colonial ceramics (tin- and lead-glazed wares including Red-brown and Galera Ware and Majolicas), later European ceramics, bone- and sand-tempered Indian ceramics and chipped stone tools, as well as quantities of animal bone. Investigators also identified several features (distributional patterns and other traces) as a faunal refuse dump with bison and cattle remains, an Indian ceramics dump, and the remnants of an early 19th-century jacal structure, perhaps related to one of the early ranching operations.

Sources

Two publications consulted for this short section provide a wealth of fascinating detail on the area’s rich history and the evidence uncovered at the site, including many additional photos. Archeologist Cynthia Tennis of the Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Texas and other researchers surveyed the regional ethnohistory and analyzed the site evidence for a report of findings with the Texas Department of Transportation. Historian Robert H. Thonhoff consulted with area landowners and visited several other intriguing related sites for his award-winning book, El Fuerte del Cibolo, Sentinel of the Bexar-La Bahia Ranches, documenting the fort and its history, with illustrations by Jack Jackson.

Tennis, Cynthia L.

2001 Archaeological Investigations at a Spanish Colonial Site (41KA26-B),

Karnes County, Texas. Texas Department of Transportation Environmental Affairs

Division, Archeological Studies Program, Report No. 26, and Center for

Archaeological Research, the University of Texas at San Antonio, Archaeological

Survey Report, No. 302.

Thonhoff, Robert H.

1992 Fuerte del Cibolo; Sentinel of the Bexar-La Bahia Ranches. Eakin

Press. Austin.

Links

Fuerte de Santa Cruz del Cibolo in Handbook of Texas Online