The

Archeology - Bone Bed 2

The

Archeology - Bone Bed 2

| Bone Bed 2 is the complex deposit of bison bones dating to at least 11,300 years ago (9300 B.C.), during Paleoindian times. This deposit covers most of the southern half of Bonfire Shelter and continues downslope outside the shelter's mouth. The finding of 10 Paleoindian dart points and fragments, as well as other chipped-stone tools, and one small hearth amid the bones leaves no doubt that humans were responsible for creating Bone Bed 2. The upper surface of Bone Bed 2 parallels the modern surface of the shelter and is covered by 4-8 ft (1.2-2.4 m) of cave sediments and cultural layers including Bone Bed 3 and the Fiber Layer. Bone Bed 2 is thickest (about 1.5 ft or 46 cm) at the foot of the steep slope of the talus cone (directly beneath the cleft in the cliff above) and gradually thins to the north and toward the rear of the shelter. It covers an area measuring at least 50-x-140 ft (15-x-43 m). Through excavations and analyses of the findings, a number of interesting insights have emerged.

Many of the buffalo that were driven off the cliff must have fallen on the outer slopes of the talus cone and came to rest outside the protective overhanging roof of the shelter. In other words, the preserved portion of Bone Bed 2 probably represents only half or less of the extent of the original layers of bones as they existed at the time they were formed. Although bone fragments can still be seen eroding from the talus slope below Bonfire Shelter, most of the bones and debris that covered the area have been destroyed by natural erosion and weathering. Nonetheless, what was left in the shelter is a most impressive and informative deposit.

Excavators have been able to distinguish three separate, overlapping layers of bone in Bone Bed 2 that formed as the result of at least three separate bison jump events. This phenomenon is particularly evident in deposits at the south end of the shelter, on and near the talus cone. The 1963-1964 excavators were not able to consistently separate the three layers in toward the rear of the shelter and northward from the talus cone area. With better lighting, the 1983-1984 excavators were able to distinguish all three layers in the central area of the shelter. During the 1963-1964 work, the middle layer in the vicinity of the talus cone was observed to consist of heavily burned and fire-fractured bone, similar to that in Bone Bed 3, whereas the upper and lower layers of Bone Bed 2 were unburned. Lacking any evidence of intentional burning, archeologist Dave Dibble reasoned that the Bone Bed 2 burn event was also the result of spontaneous combustion like that of Bone Bed 3.

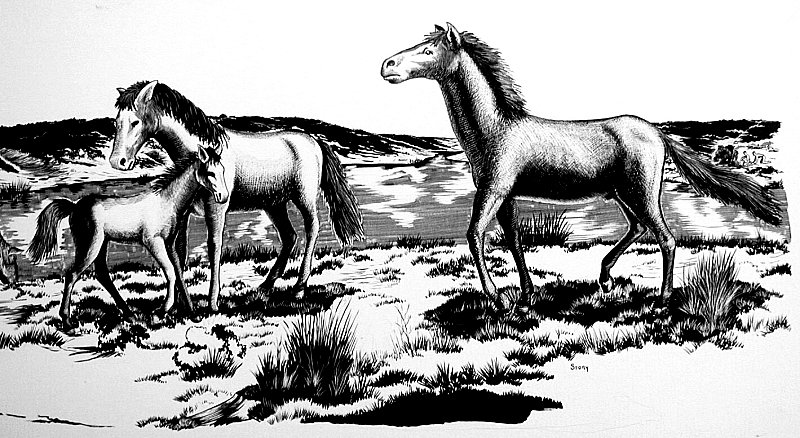

The lowest portion of Bone Bed 2 also contained the bones of at least one horse. The single horse bone found in the 1963-1964 work was interpreted as probably being an intrusive bone from Bone Bed 1. But the later excavators found a series of horse bones including teeth, long bones, and skull fragments clustered together at the contact between the lowest two layers of Bone Bed 2. Its age at death was determined to be between one- and one-and one-half-years old. Whether this animal was swept up in one of the buffalo stampedes or introduced into the site is unknown.

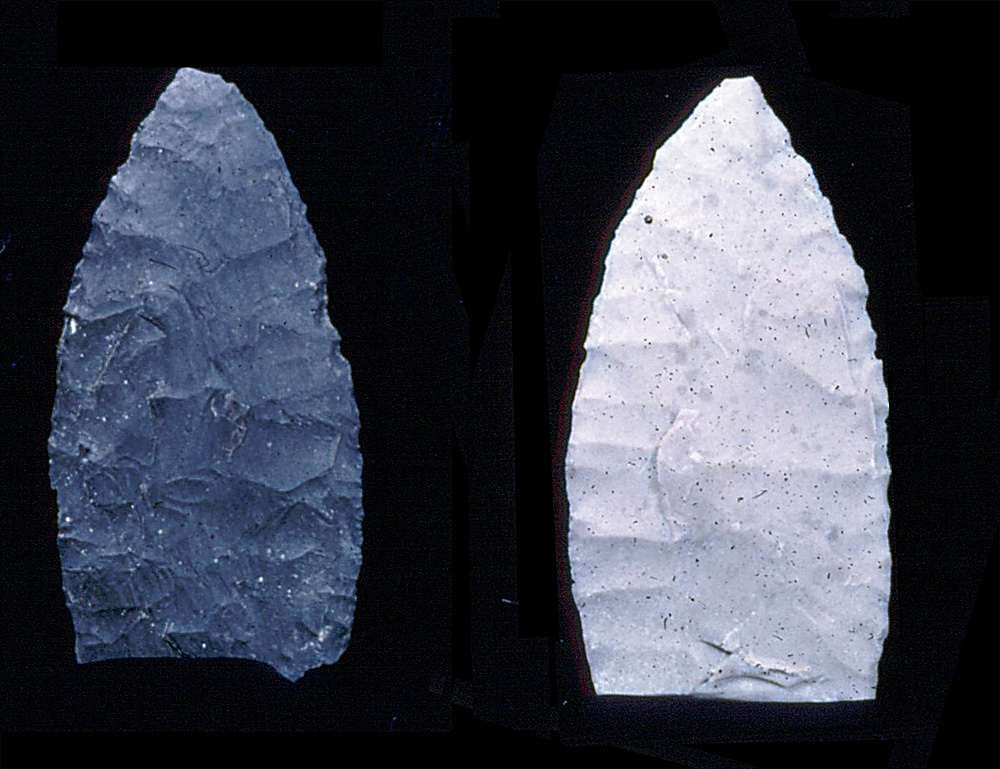

Three radiocarbon assays on charcoal from a small hearth in the uppermost layer of Bone Bed 2 and a fourth assay also on scattered charcoal from the same layer indicate that the last jump event occurred sometime between about 9300 to10,150 B.C. or about 11,300-12,150 years ago. These overlapping assays provide end dates; the lower two layers were deposited earlier, but how much so is unknown. Some evidence comes from the artifacts. Five essentially complete and five fragmentary Paleoindian dart points were found in Bone Bed 2, including one Folsom point from the lowest layer and four points classified as Plainview points, one of which (second from right) came from the uppermost layer. Noted Paleoindian lithic expert, Mike Collins, believes that two of the fragmentary specimens may be Clovis points, including one that was found in the lowest layer (white specimen on right). He also identifies one of the so-called Plainview points as a Midland point, a type thought to occur at the same time as Folsom (ca.10,000 -11,000 years ago or 8,000 - 9,000 B.C.). Taken together, the radiocarbon assays, the diverse set of Paleoindian points, and the presence of three distinct layers with different matrices, suggest that Bone Bed 2 may have formed as the result of at least three jump episodes that may span as much as 2,000 years. As Dave Dibble emphasized, several jumps closely spaced in time may have contributed to the formation of any one layer without leaving any surviving evidence; thus more than three jump episodes may have taken place.

Today, over 30 years after the first report on Bonfire Shelter was published, Bone Bed 2 remains the earliest and southernmost example of a definitive buffalo jump. At the time the site was first published, archeologists familiar with the Northern Plains dismissed the evidence from Bonfire and argued that the technique of organized bison drives was not used until the first millennium B.C. Even today a website developed by the Canada national park system shows the purported distribution of bison jump sites as strictly a phenomenon of the Northern Plains. The idea that Paleoindians were not capable of orchestrating jumps and other highly organized mass kills has been shredded by the discovery and documentation of numerous locales in the southern Plains including the Olsen-Chubbock site in eastern Colorado and the Cooper site in Northwest Oklahoma. In a 1970 article in Plains Anthropologist, Dibble reported new information on Bonfire, including two additional radiocarbon assays (only one was available when the original report was issued) which confirmed the Paleoindian age of Bone Bed 2. He also reviewed his argument that Bone Bed 2 was indeed the result of at least three carefully orchestrated drives as opposed to random events. At the time, the prevailing notion was that small groups of highly nomadic hunters roamed vast distances searching for big game and sometimes got lucky. Dibble felt that the evidence at Bonfire was of "an effective exploitive technique" which would have required the cooperation of a relatively large number of people acting in concert and having, as he put it, "extra-familial authority structure." In other words, this was not the work of a few unsophisticated family bands who got lucky, but that of a larger social group who carefully selected the place, targeted a particular herd, stampeded and directed the animals in some ingenious fashion, and who efficiently processed the meat, hides, and bones of their kill. Today few would argue with this interpretation, but at the time Dibble was pushing the interpretive window; most archeologists of the day were much more concerned with artifact typology than social organization.

In addition to the 10 whole and fragmentary projectile points mentioned above, there were 11 other stone tools and 17 unworked flakes, for a total of only 38 chipped stone artifacts. The other 11 stone tools included two small bifaces of uncertain use (they seem too small to have been useful as knives), five simple flake scrapers, and three small flake tools. It is likely that some or most of the 17 unworked flakes were also used as expedient (informal, or disposable) tools. Taken together, this is not an impressive artifact assemblage. A much larger number of chipped stone tools must have been used during the butchering of the estimated 120 animals represented by Bone Bed 2. Where are these missing tools? Since less than 50% of the deposit was excavated, we can speculate that some artifacts are still present in the unexcavated portions of Bone Bed 2. However, unless the stone tool distribution was quite uneven, with most concentrated in the unexcavated area, it would seem that more tools should have been found, especially relatively large knives and/or heavy butchering tools. The most likely explanation is that the better tools were taken out of the shelter when the butchers left. |