Cayo del Oso

Around 2,800 years ago the people of Cayo del Oso dug a grave into a clay dune facing False Oso Bay where they laid a 40-year-old woman to rest. Over the ensuing millennia they dug hundreds more graves into the dune, creating one of the largest prehistoric cemeteries in Texas. Although some of the prehistoric visitors camped nearby, leaving a succession of trash deposits, the locale apparently was used primarily as a burial ground.

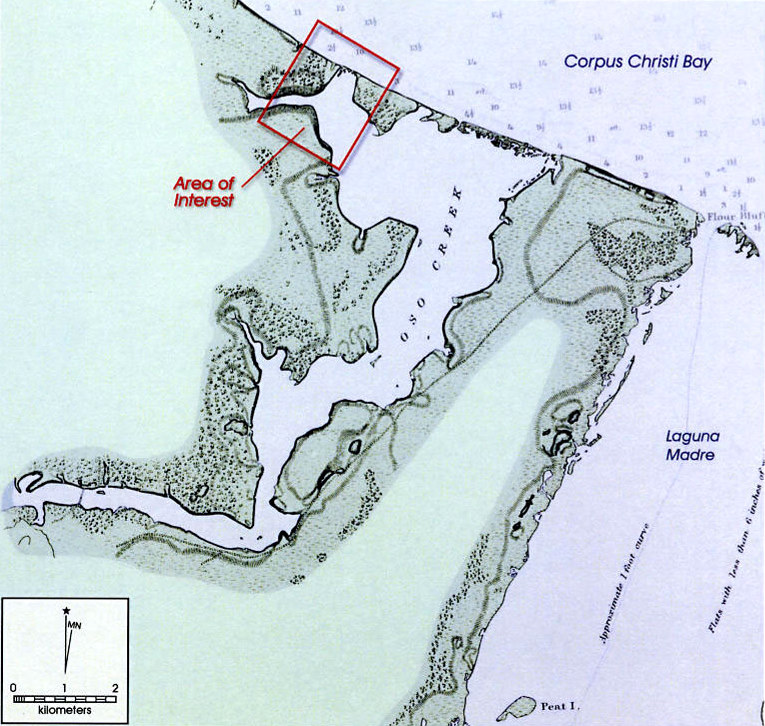

Known by a variety of names—Calle del Oso, Callo del Oso, Oso Bone Pit, False Oso, and Oso Creek—the site (41NU2) is located within the city limits of Corpus Christi where Corpus Christi Bay meets False Oso Bay—a mudflat that is alternately flooded and exposed. The site sits within a 15-foot-high clay dune, formed as the wind blew across the exposed mudflat and deposited fine particles of clay along the shore. Early investigations of the site involved some of the legendary “pioneers” in Texas archeology. More recent analysis of the skeletal remains has provided important insights into what life was like for the hunters and gatherers of the Texas coast, including dietary patterns and evidence of disease.

Cayo del Oso was first discovered by artifact collectors in the late 1800s, making it one of the earliest known prehistoric cemetery sites in Texas. After the hurricane of 1900, Martin Pearse, owner of the land on which the site was located, claimed to have observed the bones of 5,000 human skeletons exposed by erosion. Though this number is certainly an exaggeration, it is clear that the hurricane disturbed many of the site’s burials, likely exposing them for the first time. The cemetery’s sudden visibility attracted numerous local collectors who searched for artifacts and skeletal materials at the site over the next 30 years.

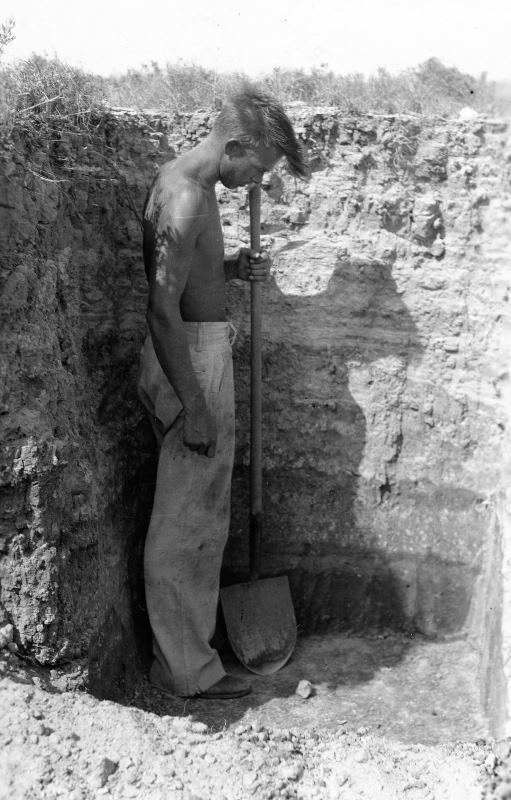

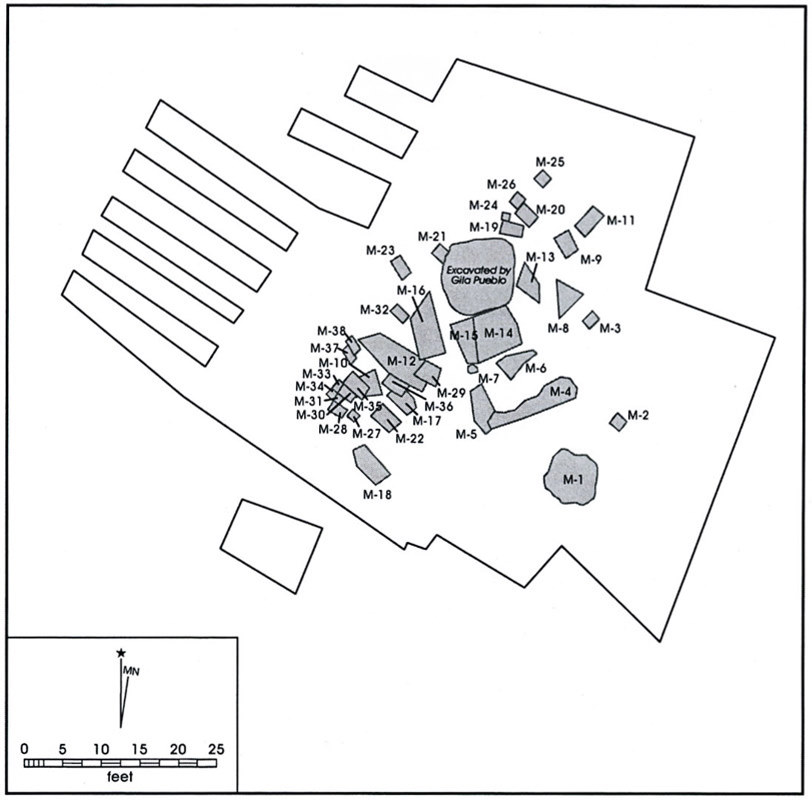

In the fall of 1929, amateur archeologist George C. Martin conducted the first excavation at Cayo del Oso. He unearthed at least 52 burials that contained only sparse accompanying artifacts: a mano, two arrow points, a shell tool and shell pendant. Martin observed, however, that the cemetery was surrounded by campsite debris that extended for more than a mile in each direction along the coasts of Corpus Christi Bay and False Oso Bay, and more than 100 meters (.62 miles) inland from the shore. It was not continuous, but consisted of dense concentrations of oyster, clam, and whelk shell ranging from 3-10 feet in diameter. Two years later, E. B. Sayles recorded Cayo del Oso during his archeological survey of Texas for the Gila Pueblo research center in Arizona. He excavated a test pit that uncovered 9 burials accompanied by several shell pendants.

Major Excavations

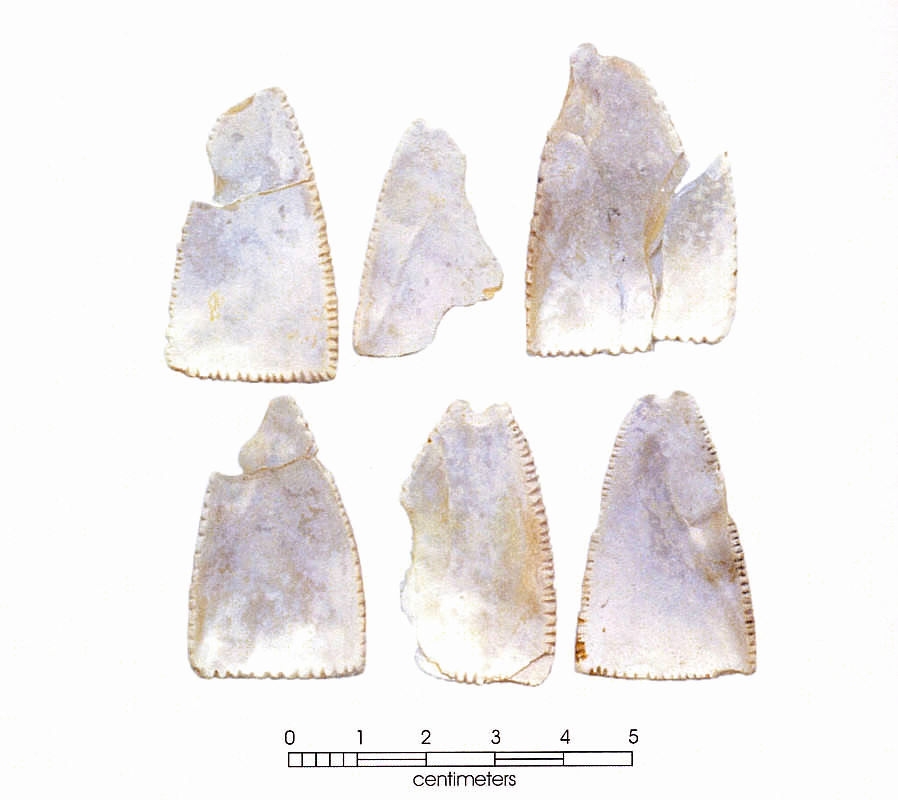

The site’s largest excavation by far was a University of Texas field school led by A. T. Jackson in the summer of 1933. The field school recorded 93 skeletons buried with 8 shell pendants, 16 beads, 2 scrapers, a deer antler tool, bone awl, shell awl, flint knife, hammerstone, dart point, and a bead made from human bone. Jackson also excavated several of the shell concentrations identified by Martin. He discovered that they were shell middens—or trash heaps—that, in addition to shell, contained animal bones, burned clay, charcoal, ash, stone tools, and waste flakes. T. N. Campbell, W. Sam Fitzpatrick, W. Armstrong Price, R. L. Stevenson, and Alex D. Krieger visited the site twice in early 1947 and removed the skeletal remains of an additional 5 individuals.

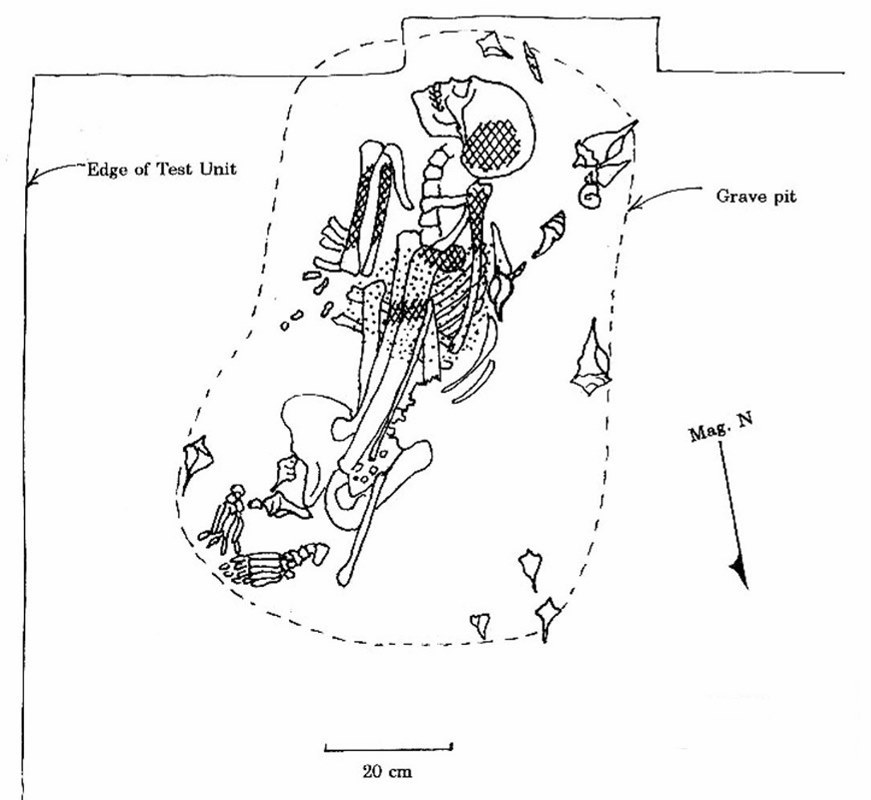

Cayo del Oso was not visited again until 1996, when the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) began a project to rebuild and widen a section of a major road that crossed the site. They performed archeological testing along the right-of-way to be impacted by the project, in order to determine the nature and extent of any remaining archeological deposits. After excavating 20 test units and 30 sediment cores, TxDOT archeologists recovered evidence of extensive deposits, including a human burial.

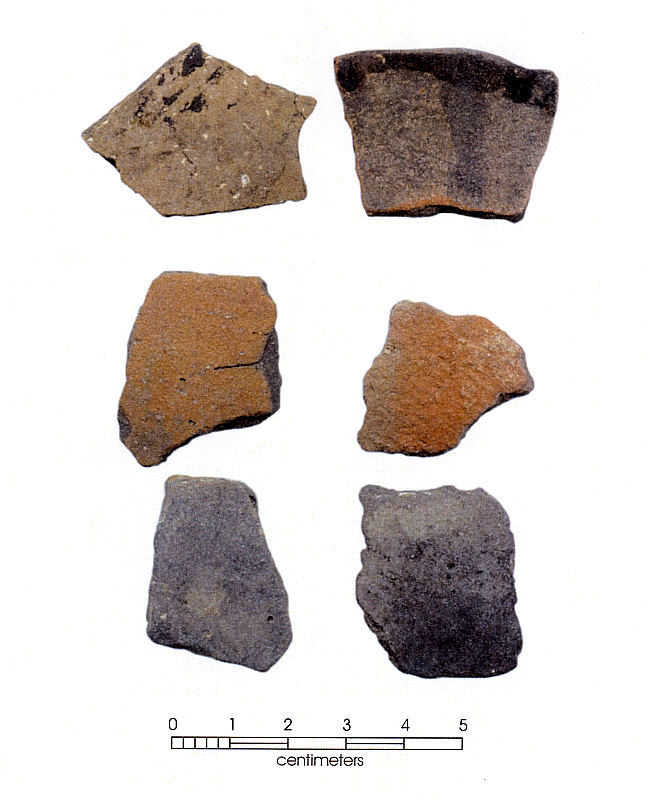

The deposits contained evidence of repeated occupations of the site from about 3,000 B.C. until A.D. 700. The occupations appear to have been relatively infrequent and of short duration, and likely focused on the procurement of black drum fish during the winter or early spring. In addition to fish, the people who visited the site ate shellfish and terrestrial mammals, mainly deer. Artifacts uncovered during the excavation include flakes, a single dart point fragment, several modified shells, and a bone pin with a simple geometric design.

The human remains uncovered by TxDOT were that of a 40-year-old female. Radiocarbon assays taken on charcoal from a fire burned within the grave pit revealed that she had been buried around 800 B.C., immediately after the clay dune she was buried in had begun to form. This makes her one of the first people to have been buried in the cemetery. It is significant that the beginning of this major cemetery appears to coincide with establishment of modern sea level as well as the related starting time of the huge, Late Archaic shell midden deposits such as Kent-Crane and Mustang Lake. Also, it is probably not coincidental that a burial excavated by Herman Smith at 41NU37, the other very large cemetery in the Oso drainage, yielded an almost identical age.

Two skeletons recovered from near the top of the dune during the A. T. Jackson excavation were radiocarbon dated to about A.D. 800. There were later graves as well, dating to the time of Europan contact. Several burials at the site contained Historic Period artifacts, including an 18th-century sword hilt.

In 2002 TxDOT contracted with the Center for Archaeological Research (CAR) of the University of Texas at San Antonio to provide further testing and monitoring of the road construction work through Cayo del Oso. In 2003 CAR archeologists uncovered the grave of a male buried in a tightly flexed (bent knees and arms) position. The burial and the excavation have yet to be analyzed and reported.

Burial Patterns

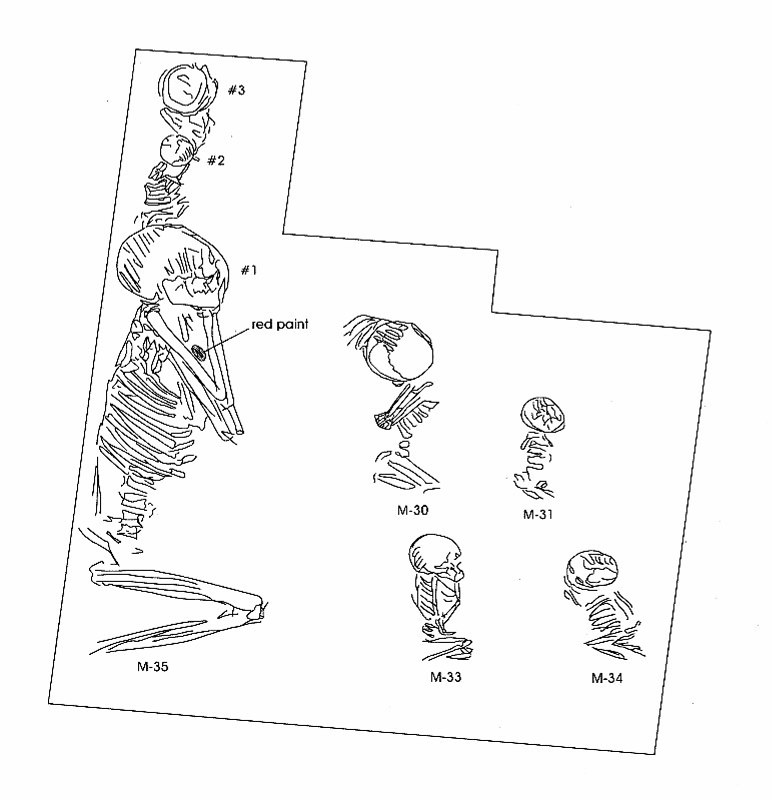

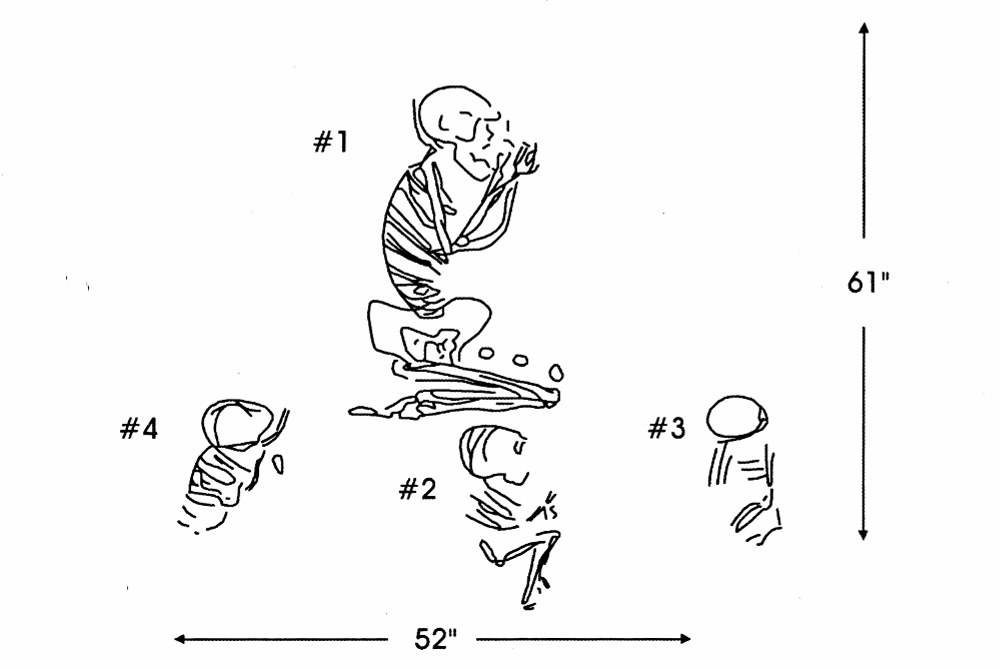

All of the individuals recorded in the cemetery were buried in a flexed position, and most were placed on their left sides with their heads facing False Oso Bay to the southeast. Nearly 40% had their hands placed over or near their faces. They all appear to have been primary inhumations, meaning that the deceased were carried to the cemetery soon after they died and their bodies were still intact. Burial offerings were few and do not appear to have been distributed in any particular pattern.

Most burials were single interments, but there were several notable multiple interments. One consisted of a 35-55 year old female buried with three infants evenly spaced at her feet. Three other burials had a similar configuration. Another multiple interment consisted of a 25-45 year old male buried with two infants and a child arrayed above his head, and three infants and an adolescent placed nearby. The spatial arrangements of these graves hints at family relationships among the people interred within them. They also indicate that, contrary to ethnographic reports from the Texas coast, interment of infants and children was part of the mortuary tradition at Cayo del Oso.

Of the 88 individuals whose approximate ages could be determined, 17 are infants (0-2 years old), 6 are young children (3-5 years old), 10 are older children (6-12 years old), 9 are juveniles (13-19 years old), 41 are young adults (20-49 years old), and 5 are old adults (over 50 years old). Overall, 54% of the burials that could be identified by sex are male and 46% are female.

What the Bones Tell Us

Recently, several different researchers have analyzed the skeletal remains from Cayo del Oso in hope of learning more about the lives of the hunters and gatherers of the Texas coast. By analyzing the teeth of the people buried at Cayo del Oso, Cynthia M. Munoz determined that their diet was based largely on marine resources supplemented with carbohydrate-rich foods, such as prickly pear, acorns, pecans, and tubers. Munoz observed that their teeth had high degrees of wear and periodontal disease—a condition that leads to tooth loss, making it difficult to chew many kinds of food.

Based on their bones, Joan E. Baker determined that the people buried at Cayo del Oso led generally healthy lives. They showed little signs of having suffered nutritional stress as children or of chronic anemia later in life. Most of the broken bones she observed among the skeletal population represented old injuries that had healed. Rather than the results of accidents, most of the broken bones appear to have been caused by fist fights or hand-to-hand combat with blunt weapons. Baker suggests that these methods may have been used by the people of Cayo del Oso to settle disputes. During his 16th-century visit to the Texas Coast, Cabeza de Vaca observed this practice among several coastal groups he encountered.

Barbara E. Jackson, James L. Boone, and Maciej Henneberg discovered that some of the people buried at Cayo del Oso suffered from bejel (endemic treponematosis). Bejel is a bacterial infection of the bones, skin, and joints. Though rarely fatal, it is a chronic, progressive disease that causes sores in the mouth and throat and leaves lesions on the bones, eventually causing disfigurement. The afflicted individuals appear to have contracted bejel in childhood and carried it with them through the rest of their lives. Very few of them had reached the disease’s final stage by the time of their death, however, suggesting that they had died from other causes.

Bejel is spread by skin contact or by shared use of eating or drinking vessels and is generally associated with small populations living in primitive, unhygienic conditions. It usually affects primitive farming communities and pastoral nomads, but can affect small bands of hunter-gatherers who seasonally aggregate into larger groups. The incidence of the disease among the people buried in the Cayo del Oso cemetery suggests that the people who used the cemetery practiced a similar mobility pattern.

The relatively sparse occupation of the Cayo del Oso site over time contrasts markedly with its use as a major cemetery. As archeologist Robert Ricklis has noted, this suggests that the importance of a given locale as a residential campsite was not necessarily congruent with its significance as a place for burial and mortuary ritual. This pattern holds for several other, larger prehistoric cemetery locales on the coast. No major cemeteries have been reported in direct association with large, intensively occupied shoreline sites. To Ricklis, this suggests that prehistoric peoples in the area maintained a fairly clear distinction between locations used frequently as domestic camps and those reserved for burial of the dead.

Contributed by TBH Assistant Editor Carly Whelan based on the sources listed below.

Sources

Baker, Joan E.

2001 No Golden Age of Peace: A Bioarchaeological Investigation of Interpersonal Violence on the West Gulf Coastal Plain. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station.

Jackson, A. T., Steve A. Tomka, Richard B. Mahoney, and Barbara A. Meissner

2004 The Cayo del Oso Site (41NU2): Volume 1, A Historical Summary of Explorations of a Prehistoric Cemetery on the Coast of False Oso Bay, Nueces County, Texas. Texas Department of Transportation and Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas, San Antonio.

Jackson, Barbara E., James L. Boone, and Maciej Henneberg

1986 Possible Cases of Endemic Treponematosis in a Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherer Population on the Texas Coast. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 57:183-193.

Mahoney, Richard B. and Harry J. Shafer

2003 Bioarcheological Analysis of a Prehistoric Burial From Callo del Oso (41NU2), Nueces County Texas. Texas Department of Transportation and Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas, San Antonio.

Munoz, Cynthia M.

2004 Native American Adaptation on the Texas Coastal Plain: A Study of the Dentition from Thirteen Prehistoric and Historic Cemetery Sites. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, The University of Texas, San Antonio.

Ricklis, Robert A.

1997 Archaeological Testing at the Callo del Oso Site, 41NU2, Nueces County, Texas. Coastal Archaeological Research, Inc., Corpus Christi.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|