Caplen Mound

The cemetery of Caplen Mound (41GV1) is located on the Bolivar Peninsula about 25 miles northeast of the present-day city of Galveston. The peninsula is a narrow, 39-mile strip of sand that separates Galveston Bay from the Gulf of Mexico. In modern times it has been a place for swimming, sunbathing, and vacationers—until Hurricane Ike swept over it in 2008, destroying the homes and beaches. But for centuries before, it was home to the Akokisa and earlier peoples who hunted, gathered, and fished around the bays and inlets of the upper Texas coast. The higher elevations of the peninsula were dominated by tall grasses and the occasional clump of coastal live oaks and other woody plants. The area was rich in food resources, and the native peoples could choose to exploit the bounty of the land or sea, depending on their need.

The Caplen Mound cemetery is located inland from the beach, with the Gulf shore 1.5 miles to the south and the Galveston Bay shore 2 miles to the north. The site lies on a low, brush-covered knoll about one meter (3 feet) above sea level. Although it is referred to as “Caplen Mound,” the circular knoll is not the result of intentional human construction. Rather, it is a small natural hill roughly 50 feet (15 m) in diameter, made larger by a shell midden that built up over decades of periodic habitation. Over the years, native peoples buried their dead within the heaps of shell refuse. That this tradition continued into Historic times is indicated by the presence of two European glass trade beads placed within one of the burials.

Investigations

For years, collectors had visited the mound known locally as the “Indian Cemetery,” and dug into the burials in search of grave objects. By the time it was brought to the attention of the University of Texas by noted Texas author J. Frank Dobie, a large part of the site had been damaged. In 1932, a team of UT archeologists led by A. M. Woolsey, under the direction of J. E. Pearce, chairman of the Department of Anthropology, conducted excavations at the site. Over the course of their work, which sampled the “heart,” or roughly a third of the mound, 66 burials (23 of which were fragmentary as a result of disturbance) were removed. It was estimated that, overall, as many as 80 individuals might have been interred in the small cemetery, at depths ranging from about 8 to 30 inches (20 to 79 cm) below the surface. As U.T. Anthropology professor T. N. Campbell noted in his synopsis, “So many burials were placed in this small area that later burials must have disturbed earlier ones.”

As is the case with many excavations of the time, records of the work are scant, and there is no profile map showing vertical placement of burials. Woolsey noted, however, some degree of layering in the mound—an upper layer of dark soil underlain with a lower layer of mixed sand and shell—as well as differential preservation of the human remains. The best preserved remains were found in the lower sand layer; those closer to the surface—having been exposed to more moisture—were in a more deteriorated, often rotted, condition. Few artifacts apparently were recovered from the area surrounding the burials, suggesting that the campsites of the various peoples using the cemetery were located elsewhere.

Although neither Woolsey nor Pearce published a report or performed an analysis of the recovered objects, an unpublished manuscript on file at TARL provides a rough description of the fieldwork. Campbell published findings from the site in the Texas Journal of Science in 1957. Osteological examinations of the human remains were conducted by George Woodbury in 1937, Joseph Powell in the 1990s, and Matthew Taylor in 2005. Powell submitted two samples of human bone for radiocarbon assays. These dates, as well as several diagnostic artifacts, indicate use of the cemetery over a period of some five to six centuries, beginning at least by A.D. 900 and continuing into the time of contact with Europeans.

Burial Patterns and Grave Objects

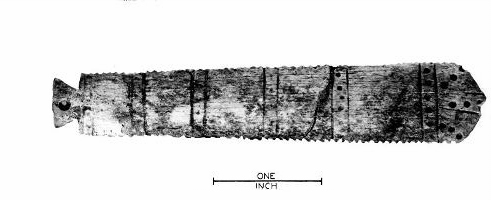

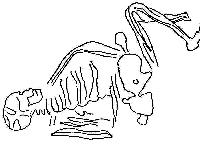

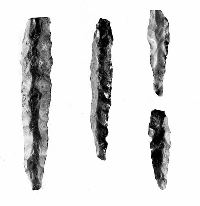

The burials at Caplen Mound were primarily adults, but also included two infants, three juveniles, and three adolescents. Most appeared to have been placed on an east-west axis in small pits, in flexed or semi-flexed position. Only a few could be identified as male burials and of the three in which orientation could be determined, all were toward the north. A small number of the burials—primarily female, and all of the infants and juveniles—were adorned with ornaments or accompanied by objects. These included marine shell gorgets and beads, a carved bone pendant, a tortoise shell rattle, stone tools and weapons (dart points; drills), ocher, and more than 100 pottery fragments. Beads were primarily of the cylindrical variety, made of conch columella, and in many cases may have been strung on cords or attached to leather clothing as ornaments. A smaller number were disc beads and perforated Oliva shell. One burial, that of a 4- to 5-year-old child, was found with 30 shell beads of four different types in the neck area.

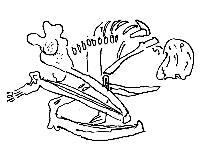

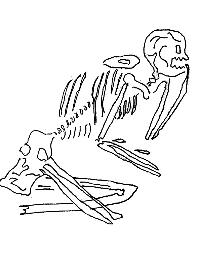

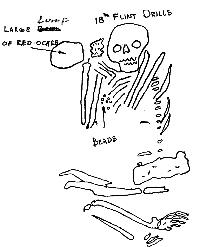

One of the more intriguing graves, and perhaps one of the earliest, was that of a female adult who had been covered with red ocher and buried with what appeared to be a shell-working toolkit (see drawing at lower right, Burial 2). A cache of 14 chipped-stone drills—possibly shell-working tools—was found on a flat rock near her head, along with two prismatic chert flakes. Two dart points (types Gary and Kent) also were found in the burial along with several red ocher lumps and nine conch columella beads, three of which were unfinished. At 24 inches below the surface, the burial apparently was one of the deepest at the site. Based on radiocarbon assay (corrected for fractionation), it is dated to A.D. 931 +/- 145.

The remains of a late fetus or very young infant was found in a grave with an adult skeleton. Eight conch shell beads lying near the skull of the adult may have been part of an ornament placed in the hair. Based on radiocarbon assay of the bone (corrected for fractionation), the burial is dated to A.D. 1307 +/-107. Although the burial was one of the closest to the surface, at a depth of only 12 inches, it was not the most recent burial at the site.

A child was buried at the site sometime after European entry into the area in the late 16th century, based on the presence of several blue and white glass trade beads placed in the grave. The burial also contained a large quantity of native-made beads of bone and shell, a large worked section of conch columella, and a tortoise shell rattle, placed near the chest of the child. According to Woolsey's report, two small black rocks had been placed inside the hollowed out turtle shell, and the plastron flaps had been sealed. The burial was discovered roughly 18 inches below the surface, and was in poor condition.

Of the excavated burials, a number were found without skulls. In other cases, skulls were found without bodies. The mandibles (lower jawbones) were missing from some of the skulls. In one area, six incomplete skulls were found within a radius of 14 inches (35.5 cm). No body parts were found nearby, although there were several beads found in the area. This skull feature may represent burials that were disturbed and reburied, or the arrangement may have had some ritual significance.

Other signs of ritual were noted. Five of the bodies had been covered with red ocher pigment. As Woolsey described one burial: “This [the ocher] was all around, over, on and under the bones. At the right of the head…was a large lump of very clean, pure red ocher.” A Pecten shell bearing a concentration of red pigment also had been placed with this individual. In another unusual burial the archeologists found a skeleton missing its skull, toes, and fingers. The body had been placed “with legs flexed to the south with feet under the buttocks.” Woolsey's report continues: “An unusual feature of the burial was the round or rounded stones found on either side of the vertebrae just about where the kidneys would be.” Campbell described these stones, totaling 13, as pigment stones.

Most of the pottery found at the site represented the local Goose Creek ware, but some were intrusive Rockport wares originating from Karankawan peoples who lived further south along the coast. There were also a few sherds of the much older Holly Fine Engraved type attributed to cultures further to the southeast, as well as one fragment Campbell identified as being of European manufacture.

What the Bones Tell Us

Analyses of the human skeletal remains (see sidebar at left: Bioarcheology of Caplen Mound) provides a complex picture of health and disease among the population buried at Caplen Mound. The people were well-fed, robust, tall, and show little evidence of chronic childhood stress. All of these factors indicate that their subsistence strategies were very successful and chronic hunger and malnutrition rare. Most individuals were able to grow to or near their genetic potential for stature; in fact, they were almost as tall as the average height of modern Americans. However, they did suffer from chronic bouts of infectious disease. An individual may have lived with these infections for months, if not years. Some individuals recovered and their lesions healed. Others may have succumbed, or died from another unknown cause while the disease was still active.

Overall, the people of Caplen Mound were well-nourished and adapted to their environment. Serious challenges to their health were present, but these were not enough to disrupt normal growth and development. Most of the individuals at Caplen Mound lived relatively long lives and were able to thrive in a dynamic, but always challenging ecosystem. The real story told by the bones of Caplen Mound is not one of how they died, but of how they lived.

Contributed by Matthew S. Taylor and TBH editor Susan Dial. A bioarcheologist, Taylor has analyzed many of the skeletal remains from Texas coastal sites including Caplen Mound.

Sources

Campbell, Thomas N.

1957 Archeological Investigations at the Caplen Site, Galveston County, Texas. Texas Journal of Science 9:448-471. Download article![]() courtesy of Texas Journal of Science.

courtesy of Texas Journal of Science.

Powell, Joseph

1994 Bioarchaeological Analysis of Human Skeletal Remains from the Mitchell Ridge

Site. In Aboriginal Life and Culture on the Upper Texas Coast: Archaeology of the

Mitchell Ridge Site, 41GV66, Galveston Island, by Robert A Ricklis, pp. 287-405.

Coastal Archaeological Research, Inc., Corpus Christi.

Rice, Jennifer L. Z.

2003 Paleopathology at Jamaica Beach (41GV5), in Galveston, Texas. Bulletin of the

Texas Archeological Society 74:141-148.

Taylor, Matthew S.

2008 Cabeza de Vaca and the Introduction of Disease to Texas. Southwestern

Historical Quarterly Vol. CXI (4): 419-427.

2006 Diachronic Changes in Hunter-Gatherer Dental Health and Disease on the Texas Central Gulf Coastal Plain. Doctoral dissertation, the University at Albany, State University of New York.

2005 Late Prehistoric Infectious Disease on the Upper Texas Coast: Caplen Mound (41GV1). American Journal of Physical Anthropology Supplement 40:204.

Wilson, Diane E.

2005 Treponematosis in the East Texas Gulf Coastal Plain. In The Myth of Syphilis:

The Natural History of Treponematosis in North America, edited by Mary Lucas

Powell and Della Collins Cook. pp. 162-176. University Press of Florida,

Gainesville.

Woodbury, G

1937 Notes on some Skeletal Remains of Texas. University of Texas Anthropological

Papers 1(5):5-16.

Woolsey, A. M. and Crew

1932 Excavation of a Burial Site, Caplen Mound, 1 ½ miles N.E. of Caplen, Galveston, County, Texas. The University of Texas Anthropology Department. Unpublished ms. On file, TARL.

|

The Bioarcheology of Caplen MoundWhen human remains are found at an archeological site, many people will ask “how did they die?” While this can be an important question, the bones of past people can tell us so much more. Each individual has a story to tell, and Caplen Mound is one place where those stories can be heard. Caplen Mound is one of several cemetery sites on the upper Texas coast that date to the Late Prehistoric and early Historic periods. Human burials have also been found at two other sites on Galveston Island: Jamaica Beach and Mitchell Ridge. The remains recovered from these sites provide a unique glimpse into the health status of the native inhabitants of the upper Texas coast. Recent analysis of the Caplen Mound skeletal sample reveal a mixed record of health. Caplen Mound individuals are relatively tall (averaging about 5’8” for men and about 5’4” for women), which indicates that their subsistence strategies were very successful. In fact, the average statures from Caplen Mound indicate that they were only an inch or less shorter than average modern Americans. Evidence that the Caplen Mound people were well-fed can also be found by examining certain features of the bones. During early childhood, the permanent teeth grow inside the bone of the upper and lower jaw. As they grow, they push out the deciduous, or baby, teeth. If an individual suffers from nutritional stress (which may take the form of illness or malnutrition) the growth of the permanent teeth will stop. Read more |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|