|

It is not probable that white settlements will be

made here for a century to come, if ever.

-West Texas "beyond the treeline," U. S. Brig.

Gen. William G. Belknap, 1851.

|

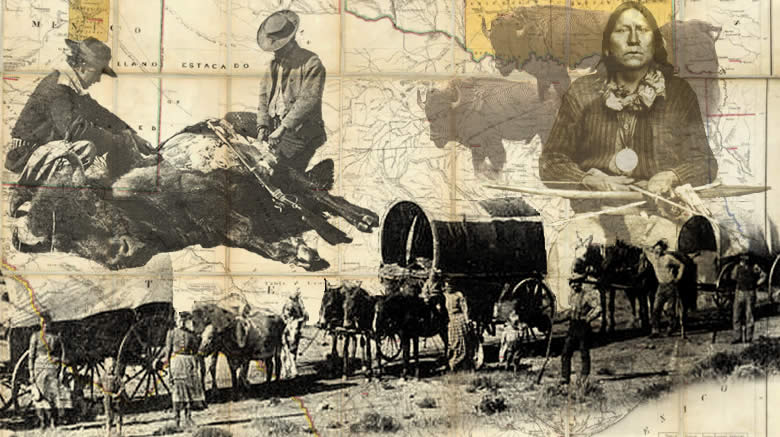

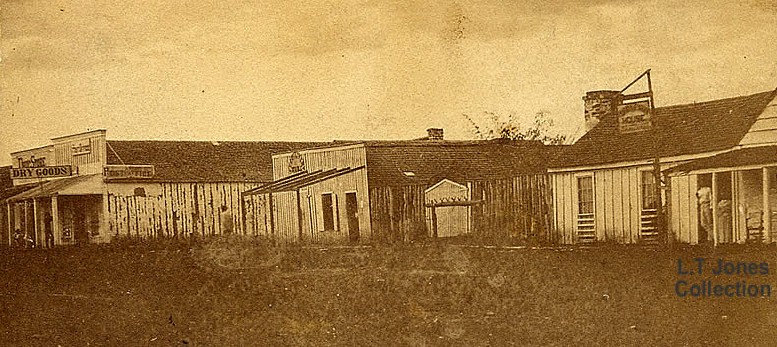

Area of settlements at the edge of

the western frontier circa 1849 to 1852 and the U.S.

forts constructed to protected them. Within a short

time, settlers moved beyond the lines of defense and

into unprotected lands. Click to enlarge.

|

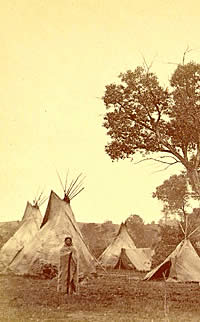

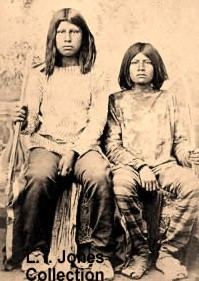

Comanche camp. Photo by William S. Soule, courtesy Wichita State University Library, A. A. Hyde Collection.

|

Bison, traditional sustenance for

the Plains tribes and later a rich commodity for Anglo

hide traders, were to come perilously close to extinction

by the end of the nineteenth century. Photo courtesy

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

The fertile terraces of the Brazos River attracted settlers

who began small farms in the Peters Colony of northwest

Texas. |

Western settlers being attacked by Indians. Small communities

on the edge of the frontier suffered the brunt of Indian

attacks in early years and served as a buffer for the

larger towns. Detail from Harpers Weekly, ca. 1870, click

to enlarge. |

Schedule of stops along the Butterfield Line from Saint

Louis to San Francisoco. Note the stations at army forts

across Texas. Click to enlarge. |

Diseases took as great a toll on settlers as they did

on Indians in some years, particularly young children

and the elderly. Gravestones, such as this one marking

the death of a child in the 1850s central Texas community

of Hoover Valley, are a poignant reminder of the harsh

frontier conditions. |

|

Anglo Texans greeted the end of the U.S-Mexican

War in 1848 with the hope that federal troops would at last

put an end to violent encounters with Indians and Mexicans

along the state's western and southern borders and open the

vast frontier to settlement. All too quickly the lure of nearly

free and unbroken land attracted a multitude of pioneers.

So rapidly, in fact, that it thrust some white settlers far

beyond the protection of the eight new military installations

established at war's end, running from Fort Worth in North

Texas to Fort Duncan on the Rio Grande.

In response, the U.S. Army in 1851 began establishing

a new line of forts a hundred miles beyond the original vanguard.

Others were located in the Big Bend country along the Rio

Grande and in extreme South Texas.

For Hispanics and Indians, who also claimed

much of this wild land as their home, the years of early statehood

left them struggling merely to survive. The Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo that ended the late war cast many Tejanos into a perilous

future, with their new citizenship shadowed by an alien legal

system and powerful economic forces. Some would fight to hold

what they had, and find their recourse outside the law.

The situation for the Comanches was even more

ominous. The effects of contact had visited the Penateka (southern)

bands with lethal consequences. Dependence on the material

goods of Anglos and a taste for alcohol broke both tradition

and will. Epidemics of smallpox and other diseases passed

along by California-bound Argonauts and other trespassers

onto Comanchería left these once-fearsome Penatekas

staring hard at the prospect of extinction. Ecological changes,

moreover, upset the annual migration of the great bison herds,

a condition that would persist into the years of the Civil

War.

If that were not enough to spell the Penatekas'

doom, traditional Indian enemies—Lipan Apaches, Tonkawas,

and others—took advantage of this turn of fortune to

settle old scores. Still others—recent arrivals such

as Kickapoos, Delawares, and Shawnees—were swept onto

the West Texas frontier by the advance of Americans far beyond

the new state's borders. Armed with superior weaponry and

well tutored in double-dealing, they further contracted the

kingdom of these one-time Lords of the Plains.

To Anglos, so many unrestrained Indian tribes

and disgruntled Tejanos posed a psychological threat illuminated

by the very real prospect of actual raids. Northern Comanches,

joined by Kiowas and individuals from other tribes, splashed

across the Red River from the Indian Territory and often probed

the length of the frontier line, keeping settlers on constant

alert. Additionally, the usual run of rootless and lawless

whites took advantage of frontier conditions to prey upon

the livestock of isolated settlers.

On balance, the Texas frontier, like so much

of America's westward expansion, held promise in one hand

and peril in the other. Settlers bet their lives and property

on the wager that chaos would quickly give way to order. In

the estimation of these plucky newcomers, the prospective

rewards were certainly worth the risks. Like their predecessors,

the Spanish colonists who in the 1700s had settled the borderlands

along the Rio Grande, they learned that all manner of hardships

might be survived with a bit of luck and the support of neighbors,

though often far afield.

As the 1850s unfolded, signs of progress offered

encouragement. However meager, any number of villages sprang

up between the first and second line of U.S. posts from Gainesville

near the Red River, to Uvalde and Brackett above the Rio Grande.

The Peters Colony, established by the Republic-era legislature

in part to attract Ohio Valley families as a buffer against

the Penatekas, beckoned farmers who, on the grant's western

edges, tilled virgin soil along the fertile creek banks and

bottomlands of the Brazos and Trinity rivers. This expansive

watershed came to be known as Northwest Texas.

In the Hill Country area, German and Alsatian

emigrants continued to adapt their small-farming techniques

to Texas' expansive spaces. Settlements such as Fredericksburg,

New Braunfels and Castroville provided a bit of European culture

on the frontier in spite of continued threats of Indian attacks.

In 1858 the Southern Overland Mail, better known

as the Butterfield stage, began cutting a path across the

plains and prairies between its terminals at Saint Louis and

San Francisco. From Sherman to El Paso a series of stations

presented anchors around which communities seemed surely to

emerge.

Other newcomers to northern Texas learned that

the Western Cross Timbers, a veritable "cast iron forest,"

provided natural fencing. Indeed, many names later associated

with the great post-Civil War cattle empire—Hittson,

Goodnight, Slaughter, and others—seeded their first herds

on the tall grass of these rocky, but fertile prairies closed

in by the dense forests.

Just when it seemed as if the frontier was beginning

to join the mainstream of Texan society, Anglo-Indian conflicts

and the Civil War reversed most of this material progress.

Warrior bands—mostly from the Indian Territory—had

never ceased to probe the defensive gaps along the line of

the settlers' advance. For their part, the state and federal

governments were often at odds, flip-flopping between policies

of peace and war.

Adding to the sense of anxiety, the federal

government in 1854 leased four leagues of land for an Indian

reservation along the Brazos River below Fort Belknap. A second

reservation upstream was added for the Penatekas near Camp

Cooper, on the Clear Fork of the Brazos.

Many settlers expressed their admiration for

the Indians' efforts to take up farming and stock raising,

but others—more outspoken in their criticism—would

not be satisfied until the native peoples were either exterminated

or run out of Texas for good. While the rest of the state

was preoccupied with rumors of slave insurrections, frontierspeople

were stirred into the same kind of frenzy when a Jacksboro

weekly, The White Man, embarked on a sensational campaign

that preyed on settlers' fears and turned every rumor to fact.

The pioneers' sense of dread was somewhat allayed

in 1858 by news of two signal victories over their Plains

adversaries. That spring, Texans led by ranger captain Rip

Ford reported the defeat of over 300 determined warriors at

the Battle of the Washita, in Indian Territory. Not far from

there, near Wichita Village, U.S. Captain Earl Van Dorn routed

about 500 Comanches and Kiowas that fall.

Meanwhile, The White Man grew ever more

vocal. Words grew into deeds, climaxing in the Reservation

War of 1859 that pitted militiamen of Northwest Texas against

the Indians on both reservations. While no pitched battles

ensued, the affair resulted in the expulsion of the native

peoples.

At last it seemed as if Anglo Texans had gained

control of the frontier. The Civil War intervened, however,

proving that the worst of the settlers' troubles was only

beginning.

The Civil War cost pioneer folk both the protection of the

federal troops and much of its home guard, as many militiamen

took up arms and marched east to defend the South. Indians,

revitalized by feelings of revenge, took advantage of the

situation and attempted to reclaim their former homeland and

hunting grounds.

|

Rio Grande City, circa 1853. This

peaceful scene belies the violence that frequently erupted

in this and other early Texas border towns. As the artist-soldier

Capt. Arthur T. Lee wrote, Rio Grande City "could

boast more crimes of murder, robbery, assassination,

and outlawry generally, than all the rest of the Texas

cities… ." Detail of painting, courtesy of

the Rochester Historical Society. Click for full image.

|

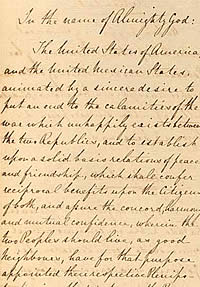

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in

1848 brought the promise of peace between the United

States and Mexico. For many Tejanos, however, the treaty

brought an alien legal system along with a change in

citizenship. Some victims of the new economic and political

order fought back outside the law. Treaty (page 1),

courtesy the Library of Congress. Click to enlarge.

|

|

On balance, the Texas frontier, like so much of

America's westward expansion, held promise in one hand

and peril in the other. Settlers bet their lives and

property on the wager that chaos would quickly give

way to order.

|

Hovering goddess-like above the

westward moving pioneers, this allegorical female came

to symbolize the virtue of taming the western frontier,

what some considered America's "manifest destiny."

Painting entitled, "American Progress," by

George Crogutt, 1873. Image courtesy of the Library

of Congress.

|

As settlers pushed farther west on the Texas frontier

in the 1850s, new army posts were constructed to provide

a measure of protection. Click to enlarge. |

"The Old Stagecoach of the Plains."

The coming of the Butterfield stage line to Texas, with

its series of passenger stops, provided further anchors

for settlement along the frontier. Painting by Frederick

Remington, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth.

|

Substantial houses of stone and plaster

with a European flair were built in early settlements

such as Castroville. The house shown is that of Henri

Castro, founder of the 1840s colony west of San Antonio.

Click to see full image.

|

|