Mass Kills

With skillful planning, organization, and luck, prehistoric hunters could occasionally succeed in killing dozens or even hundreds of animals at a time, using little or no weaponry. Archeologists call sites where some of these kills occurred, "jump sites." To the animals, however, it was a "plunge of death."

The "jump" kill involved what seems like a simple plan. Hunters would frighten or spook a herd of buffalo off of a cliff or high bluff. But to make the plan work required strategy. The right site had to be located, the animals had to be directed to the spot, and they had to be stampeded over the edge.

At the Bonfire jump-site in southwest Texas, archeologists found the bones of hundreds of buffalo that plunged over a cliff to their death on a massive pile of rocks. Native American hunters in the area had used the kill site as early as 12,000 years ago! It is clear, however, that prehistoric hunters did not stage mass kills frequently. They were once-in-a-lifetime events for the hunters. There was evidence of perhaps only four successful jump-kills at the Bonfire site over its long history. Many other times hunters must have tried and failed to trick the buffalo into "falling for" their plan.

There were other methods for mass kills. Prehistoric hunters also herded buffalo into enclosed areas, such as box canyons, or into corrals made of poles where they would kill the trapped animals.

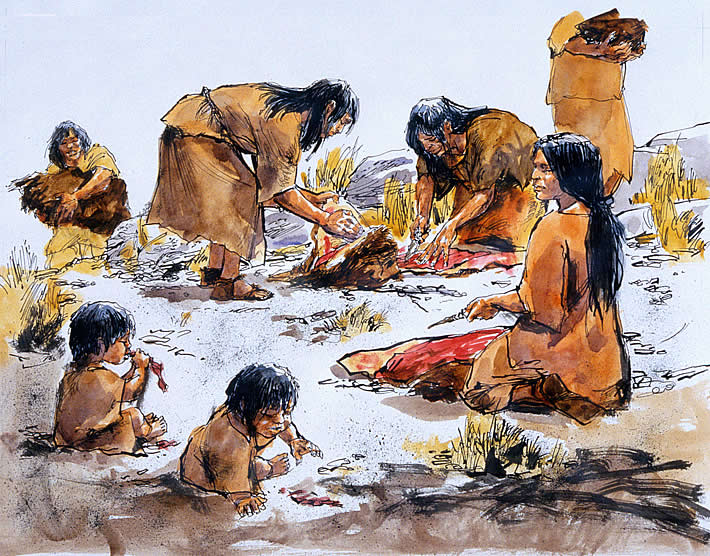

Butchering the Kill

After the jump, hunters and women from the prehistoric group would begin the massive task of skinning and butchering the animals. They dragged the animals' enormous hides away from the butchering area to later be tanned, or softened, by smearing them with fresh buffalo brains. Hunters ate the best meats, including the tongues, on the spot, and often drank the animals' warm blood.

Hundreds of pounds of meat would be sliced into thin strips that were spread out on wooden racks to be smoked or dried by the sun. The dry strips (jerky) could then be stored for later use, often as an ingredient in pemmican (an early trail mix). Enormous leg bones were crushed to get at the rich marrow inside, and bone bits were boiled to capture the fat in a greasy broth. The butchering, smoking, and skin curing process lasted weeks, but the payoff was huge. Hundreds of pounds of meat, bone for tools, hide for cover and clothing, hair for ropes, sinews for cording—the list of useful items from a buffalo seems endless!