McFaddin Beach: This Site Is All Washed Up!

Photograph courtesy of Matthew White. |

|

|

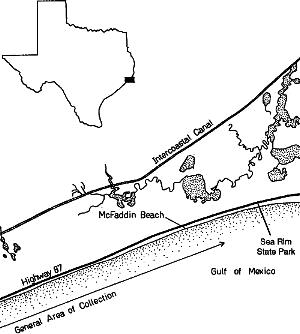

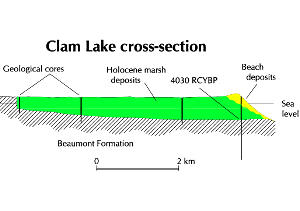

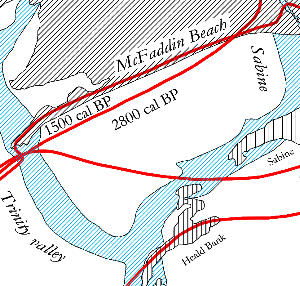

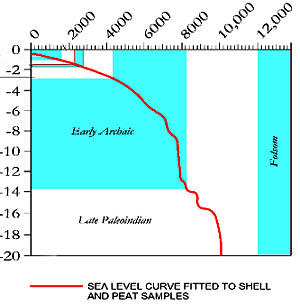

It seems clear that artifacts and fossils are arriving on the beach from a submerged, offshore source area, perhaps at no great distance or depth in the Gulf. It is also clear that both the present beach area and the offshore source were actually high and dry parts of the inland coastal zone until relatively recently in geologic history. This was an interfluvial area between the Trinity River valley to the southwest and the Sabine River valley to the northeast. During the Pleistocene, or last ice age, so much water was sequestered in major continental ice sheets (like the Laurentide ice sheet in North America) and in alpine ice sheets rimming the earth’s mountain ranges, that global sea level was drastically lowered. Some of the latest and most interesting research on sea level history comes from Barbados, on the western edge of the North Atlantic, and it is based on isotopically dated samples of four species of drowned corals, one of which is known to grow at a restricted depth range. Uranium-thorium dating is used to fix the ages of coral reefs that were killed by postglacial sea level rise. These new studies suggest that maximum glaciation (and consequently, minimum sea levels) occurred about 26,000 calendar years ago, with sea level about 125 meters lower than at present. This is about 5000 years earlier and five meters deeper than the consensus values that most geologists have customarily used (21,000 calendar years, or 18,000 radiocarbon years for the Last Glacial Maximum, and a 120 m lowering). At 26,000 B.P., the Gulf shoreline in the upper Texas coast region would have been perhaps 200 km to the southeast of its present position. It should also be noted that this is just the latest lowering of Gulf sea level during the Pleistocene — there were earlier highstands and lowstands. By 14,000 years ago, sea level was rising rapidly because of ice sheet melting. Assessing the rate of rise in the Gulf is complicated by the fact that eustatic sea level indicators in the Gulf of Mexico tend to plot higher than contemporaneous indicators elsewhere in the world (for discussion, see the reference by Simms and others in “Sources”). The oldest radiocarbon dated shell or peat samples cored from the northern Gulf are about 19,700 calendar years old. If we rely on the Barbados coral data, by about 13,300-13,500 calendar years B.P. (when the archeological record at McFaddin Beach begins with the deposition of Clovis points at the source area) sea level still stood about 65-68 m below the present level, the shoreline was still 175 km away, and the site area still well inland. At about 10,000 calendar years B.P., when various types of Late Paleoindian projectile points were being deposited at the site, sea level had risen to 20 meters below the present level. At about 7700 cal B.P., a barrier shoreline developed about 55 km southeast of the McFaddin area. The rate of sea level rise (and flooding of the continental shelf) was especially rapid in the early Holocene from about 9000 to 7000 cal B.P. Without knowing where the actual source area for the McFaddin artifacts is located, it is impossible to say exactly when the area was flooded and rendered inaccessible for habitation, but there are some artifacts from the beach that Stright classifies as “transitional Archaic” (about 2350-1250 cal B.P.) and Late Prehistoric (about 1250-400 cal B.P.). By the time these were discarded, the source area may well have been flooded, which raises the possibility that these most recent artifacts might have been discarded on the beach, rather than washing ashore like the earlier material. During the period of lowered sea level, the combined channels of the Sabine River and Calcasieu River incised the exposed continental shelf, running southwestward roughly parallel to the present coast and about 30 km out from it, joining the Trinity River channel, then turning southward. The Deweyville terrace system that flanks these rivers continues onto the continental shelf, running under the waters of the Gulf. As sea level rose, the river valley was flooded, with the contact between fresh and sea water turned into an estuary. Marine coring in the 1980s by archeologists penetrated a Rangia shell deposit and a bone concentration with burned and unburned bone (water snake, amphibian, fish), fish scales, seeds, and nutshell. These may be bayside archeological sites occupied as the Gulf waters flooded what had been an estuary. A radiocarbon assay of 8055 ± 90 radiocarbon years B.P. on some of the shell equates to about 8500 cal B.P. (marine database, using standard marine reservoir age). Estuarine deposits dating from 7400 to 7400 cal B.P. (buried under Sabine Bank) and 8400 to 7700 cal B.P. (buried under Heald Bank) have been cored offshore. At 7700 cal B.P., the shoreline was still some 50 km away; by 5300 B.P., it had approached to about 40 km away; and by 2800 cal B.P., was about 5 km away from McFaddin Beach. By 1500 cal B.P. (or about 450 A.D.), the shoreline was approximately in its present position. Two lines of vibracores punched across the valley axis contain pine, oak, juniper, cypress, grass, sedge, and other pollen types suggesting vegetation similar to that found on the coastal plain today. What happened after the middle Holocene, or about 6000 cal B.P., is in dispute. One group of geologists insists there has been a fluctuating series of late Holocene highstands — periods during which sea level actually stood higher than today and covered part of what is now dry (well, dry to marshy, perhaps) land, evidenced by a series of inland beach ridges radiocarbon dated to that period. Another group of geologists insists that the beach ridges are really storm surge deposits, and document Late Holocene climatic intervals with increased storminess. They maintain that sea level has risen more or less smoothly to its present level and has never onlapped the land during the Holocene.

Vertebrate FossilsThe vertebrate fauna found on the beach is similar to other poorly-dated Rancholabrean faunas of southeast Texas and adjacent Louisiana (the Rancholabrean is the most recent of the Pleistocene land mammal ages, beginning at least 300,000 years ago), such as the Damon Mound, Texas City Dike, Avery Island, and Sims Bayou faunas. A fragment of proboscidean tusk from McFaddin Beach was assayed at 11,100±750 radiocarbon years before present (the 13C value is -24.3 ‰) by the Gulf Oil Corporation, but the assay was done over 30 years ago, and it is not clear if the material dated was the collagen fraction, or the collagen plus apatite. This assay equates to about 12,000-13,850 calendar years ago. Many of the fossils are mineralized or stained by organic or mineral deposits.

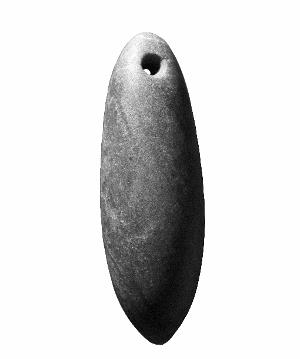

The McFaddin Beach fauna is clearly not an unbiased vertebrate sample, because the only small mammals present are a cotton rat and a prairie dog. Fossil bones from small animals like rodents have probably been overlooked by beachcombers. But it is interesting to note that aquatic animals make up a significant part of the list: gar, catfish, sunfish, various turtles, alligator, otter, beaver, raccoon, capybara, and tapir all live in or near freshwater habitats. According to Paul Tanner, fossil turtle shell, horse bones, and deer antler are most common. Man of the terrestrial species (prairie dog, cotton rat, cottontail, bison, horse, peccary, pampathere) were either grazers or rooters, living in open grassy or brushy habitats rather than woodland. A few others come from wooded (mastodon, ground sloth) or woodland gap (tapir) habitats, and these may be from gallery woodlands that lined streams crossing the exposed continental shelf. There are perhaps two different models to explain the origin of the beach fauna. Damon Mound, a Brazoria County salt dome, furnishes an example. At Damon Mound the sediments overlying the salt diapir are thought to be point bar and levee deposits of Beaumont age. The fauna is very similar to the McFaddin fauna, and the bones probably belong to animals that lived and died in the ancestral Brazos or San Bernard River valleys, either in the immediate vicinity or having been redeposited downstream by flooding. Upward diapir growth during the Pleistocene and Holocene has pushed the overlying alluvial sediments upward into a prominent mound, exposing them to erosion and quarrying activities. If this model applies also to the McFaddin dome (which is buried under the seafloor, unlike Damon Mound), it could indicate that most of the McFaddin bones predate and are unrelated to human occupation. The second model is more speculative because so little is known about the McFaddin dome. If joints or faults allowed saline springs to develop some 400 meters above the McFaddin dome while the continental shelf was exposed, they might have been attractive to a variety of herbivores. Many herbivores resort to salt licks (both wet and dry) and resort to geophagy (earth eating) to obtain supplemental elements (such as sodium, magnesium, iodine, and carbonates) during some seasons. This often happens during the transition from low-quality winter forage to rapidly greening spring vegetation, and it is especially important to females who have to meet the demands of lactation, growth, and weight regain during the spring season. Forage, especially early spring forage, may contain toxins (these are plant defense strategies to ward off grazers) or high levels of acidity. Clay consumption may help to buffer rumen acidity and neutralize secondary plant compounds such as tannins and alkaloids. In Kenya, licks frequented by African elephants contain measurably higher levels of sodium and iodine in the clay that is eaten. Some researchers have also suggested that licks serve a social function, as a “meetup place” for gregarious herbivores. In British Columbia, as Ayotte and others have noted, “wet licks are associated with groundwater springs, often becoming treeless areas of deep mud after years of use by moose and elk.” The resemblance to some of the mammoth kill sites at cienegas in the western US or the Quaternary bone deposits at Saltville, Virginia, is striking, and it could well be that salt licks on the coastal plain attracted not only mammoths, bison, and horses, but also Paleoindian hunters, who probably would have been thoroughly familiar with the congregation times and gender composition of herds. A Master’s thesis study by Laura Abraczinskas of the spatial association between salines and proboscidean finds in Michigan was inconclusive, in part because of incomplete documentation of some of the sites. All of this is simply speculative, however, until we know more about the geology of McFaddin Dome. Artifacts from the Beach |

|

|

|

|

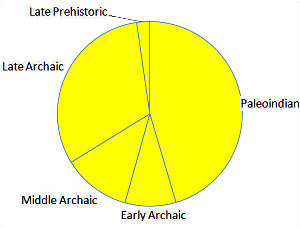

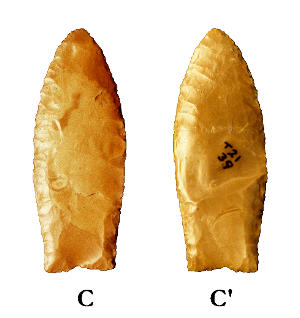

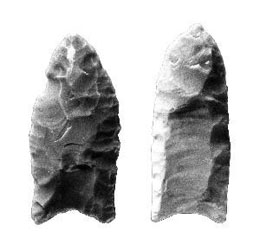

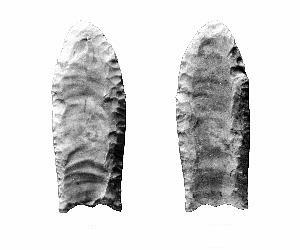

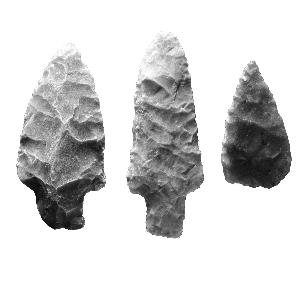

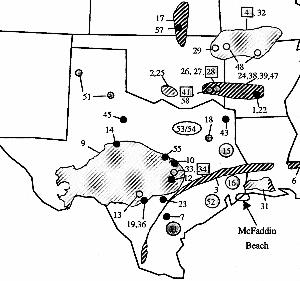

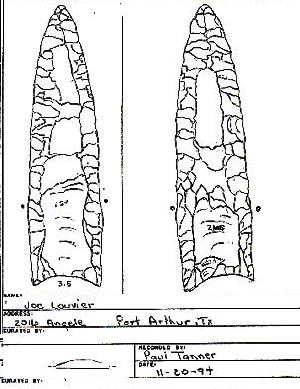

Although Melanie Stright studied only the five best-documented collections, compared to the 27 that were examined at the 1991 conference, her research remains the chief source of information on the artifact assemblage. When looking at time-diagnostic artifacts (mostly projectile points, but also including such things as Clovis blades and beveled knives), the most striking aspect of the assemblage is the large proportion of Paleoindian artifacts — probably about 45% of the time-diagnostic items. Late Archaic artifacts (defined here as after about 2800 cal B.P. and before the Late Prehistoric) probably account for almost 32%. Early and Middle Archaic artifacts are much less well represented, although it must be admitted that very little is known about this span of time in East and Southeast Texas. Stright’s study sample included 53 San Patrice, 36 Scottsbluff, 27 Dalton, 21 Clovis, 13 Plainview, 13, Pelican, 3 Hell Gap, 2 Folsom, 2 Angostura, and several other Paleoindian types. Are Stright’s five collections representative of the entire beach assemblage? We can probably assume they are, although we should remember that there are now five times as many Clovis points documented as in her study sample. Presumably the proportional representation of different time periods would remain about the same if we could inventory every artifact found at the beach. For most sites in Texas with long occupational histories, it is usually the case that post-Paleoindian material vastly outnumbers the Paleoindian collections. The usual explanations are that early populations were highly mobile and thinly scattered, not burdened with much material culture, and that early components have had a much longer time to suffer the vicissitudes of site destruction. A collection where Paleoindian material dominates is highly unusual. It is also clear that in Stright’s study sample, the earliest Paleoindian types (Clovis, Folsom, Midland) are less numerous than somewhat later Paleoindian types like Scottsbluff, Angostura, and Early Side-Notched, and much of the Paleoindian material consists of eastern woodland artifact types such as Dalton, San Patrice, and Pelican. According to archeologist Dennis Stanford, many of the Clovis points resemble eastern rather than western manufacturing styles.

Also unexpected is the fact that many of the projectile point types with eastern affiliations are made of Edwards chert, either from far-distant outcrops or from moderately distant gravel sources (terrace gravels of the Guadalupe, Colorado, or even Colorado and Brazos rivers, perhaps). Many, perhaps most, of the San Patrice and Pelican points, and other types such as Big Sandy, Dalton, Motley, Epps, Gary, and Delhi-like are made of Edwards chert. It is clear that much of the lithic industry, not only in Paleoindian but also in later times, was supported by raw materials drawn from far away and from a diverse geographic supply area. Is this typical of sites in the region, or is it unique to McFaddin Beach? We should remember that comprehensive sourcing studies like this one by Larry Banks are quite rare. In most cases where lithic sources are pursued, studies focus on a single exotic artifact, or at least a small sample. Studies of very large samples like the five McFaddin Beach collections are rare, especially in stone-poor regions of east Texas and the eastern US. If we had more such studies, we might find that toolstone movement across the landscape was much more extensive than expected in post-Paleoindian times. Spatial Analysis of Artifacts |

|

|

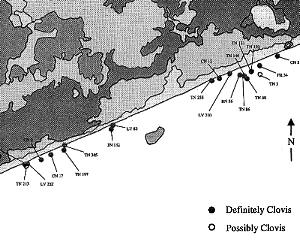

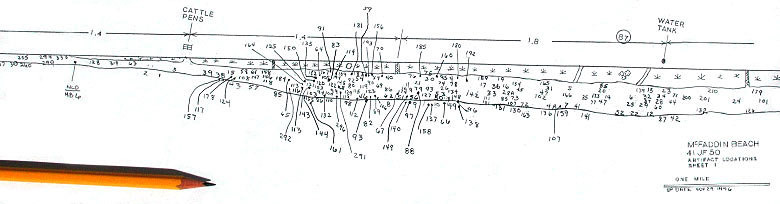

As a major focus of her dissertation, Melanie Stright studied the spatial distribution of artifacts on the beach to look for clues to the possible location and nature of sites offshore. Using plottings supplied by the five collectors who contributed data, she compiled a composite map of artifact locations. By measuring GPS coordinates on landmarks used by the collectors, she was able to compute UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator) coordinates for each artifact. Importing the data into a GIS (Geographic Information Systems) program allowed her to look for clustering of artifacts by age, date of collection, artifact weight, and other variables. Clustering of artifacts could indicate 1) environmental processes that redistribute artifacts systematically, 2) remnant patterning that hints at locations of sites offshore, or 3) systematic collector bias. When all the artifacts in the beach were plotted together, a major cluster of artifacts along the eastern half of the beach and a less prominent cluster along the western half appeared, with an area (“the gap” at the center where only seven artifacts were found. Is this area less productive because the beach is a bit steeper here, or because this area is less accessible to collectors? Artifacts are believed to come ashore as a result of seafloor erosion associated with major storm surges. Stright found that 11 major tropical storms occurred between 1970 and 1989, plus another in 1995, the years that her study collections had been acquired. During the spring and summer months, from April to September, a strong longshore current sweeps southwestward along the coast, a current that would tend to pick up any artifacts brought into shallow water by storm surges, and redistribute them toward the Bolivar Peninsula. During the winter months, from October to March, a weaker current sweeps in the opposite direction and would probably have much less effect. In support of this pattern, Stright noted that artifacts from the western cluster tended to be more heavily worn. Anyone who has been swimming or surfcasting at places like Galveston or Padre Island along the Texas coast knows how strong this longshore current can be. Swimmers and fishing weights usually come ashore some distance from where they started out. Human disturbance might be another possible source of artifact movement. Paul Tanner noted an unusually large number of artifacts along the western portion of the beach after the winter of 1983, after construction of the Big Hill brine disposal pipeline. While examining artifacts at the 1991 conference, archeologist Mike Collins noted that most of the older artifacts (particularly Clovis points) showed little evidence of wear, while many of the younger, Archaic artifacts showed abrasion from rolling in the surf and chemical pitting from exposure to seawater. He suspected that this might be evidence of scouring of stratified sites, with the younger artifacts having been exhumed several years ago, and with and older and more deeply buried Paleoindian artifacts just now beginning to be exposed by scouring. Paul Tanner has also made the same observation. In addition to studying visual plots of artifacts on maps of the beach, Stright also did a nearest-neighbor analysis of artifact locations. Nearest neighbor is a statistical test used in geography, wildlife biology, and botany to look for clustering of discrete objects. The distance between each pair of objects is computed and compared to a sample consisting of the same number of randomly located objects. The distribution can be clustered, random, or regular. Stright found that the data set as a whole was clustered, and likewise the Paleoindian artifacts were clustered — perhaps just representing the two major clusters at each end of the beach — but all other subgroups (such as Late Archaic or Early Archaic) had “regular” distributions. These results are perhaps more a result of the nearly one-dimensional sampling area and the smaller numbers of the post-Paleoindian artifacts than anything else. The beach is, after all, 32 kilometers long but only 25 meters wide. Lessons LearnedMcFaddin Beach is a textbook case for the importance of provenience and context in archeology. If we could actually see the areas of seafloor where the artifacts and fossils are coming from, we would know if any of the vertebrate fossils are associated with Clovis artifacts. Are any of these the remains of Clovis-aged megafaunal kills, or are they much older fossils scoured from some other location and brought by chance to the same stretch of beachfront? Are the Paleoindian artifacts coming from one or a few large campsites with prolonged occupations (something like the Gault site in central Texas) or from a much larger number of smaller, more widely scattered sites? Are the sites stratified, or are the Paleoindian and Archaic artifacts arriving from entirely different places on the submerged landscape? Why is there so little chipping debris in the collections? Is it because flakes, blades and flake fragments are too hard to see on the beach, or less interesting to collectors, or is it simply because toolstone was scarce and most reduction was done closer to the rock source? Why is there so little evidence of Clovis blades? Is the McFaddin Beach salt dome in any way relevant to the archeology or the artifact distribution? We would probably have answers to all these questions and more if we could actually see the submerged sites themselves, but that will have to wait for better underwater exploration technology. For now, all the really important questions remain unanswered because of the lack of provenience and context. We should also point out that because many of the beach collectors allowed their collections to be studied by archeologists, and some of them even kept map records of their finds, we nevertheless know a lot more than we would otherwise. Credits and SourcesThe McFaddin Beach exhibit was written by archeologist Kenneth (Ken) M. Brown. Susan Dial and Heather Smith developed the exhibit. Brown’s interest in archeology can be traced back to his teen years participating in Texas Archeological Society field schools, and he has been at it ever since. Awarded a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin, he has worked in the field for nearly 40 years. Ken's dissertation on the Berger Bluff site provides unique insight into the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene climatic history of the coastal plains of Texas. A Research Fellow at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, Brown has pursued interests in paleoenvironmental analysis and the study of wooden artifacts. For this exhibit, he drew on the sources listed below as well as information gathered during visits to the McFaddin Beach site and examination of various artifact collections. Print SourcesGulf Coast Geology Faure, Hugues, Robert C. Walter and Douglas R. Grant Simms, Alexander R., Niranjan Aryal, Yusuke Yokoyama, Hiroyuki Matsuzaki, and Regina Dewitt Salt Licks, Salt Domes, and Megafauna Autin, Whitney J., Richard P. McCulloh and A. Todd Davison Ayotte, Jeremy B., Katherine L. Parker, and Michael P. Gillingham Flores, Mary D. Gagliano, Sherwood M. Hamlin, H. Scott Jenkins, John T. Jr. Jones, Robert L. and Harold C. Hanson Njiiri Mwangi, Peter, Antoni Milewski and Geoffrey M. Wahungu Saunders, Jeffrey J. Geologic and Sea Level History Cohen, Denis, Mark Person, Peng Wang, Carl W. Gable, Deborah Hutchinson, Andee Marksamer, Brandon Dugan, Henk Kooi, Koos Groen, Daniel Lizarralde, Robert L. Evans, Frederick D. Day-Lewis, and John W. Lane, Jr. Gagliano, Sherwood M., Charles E. Pearson, Richard A. Weinstein, Diane E. Wiseman, and Christopher M. McClendon Milliken, K. T., John B. Anderson, and Antonio B. Rodriguez Morton, Robert A., Jack L. Kindinger, James G. Flocks, and Laura B. Stewart Peltier, W. R. and R. G. Fairbanks Simms, Alexander, Kurt Lambeck, Anthony Purcell, John B. Anderson and Antonio B. Rodriguez Warny, Sophie, David M. Jarzen, Amanda Evans, Patrick Hesp and Philip Bart

McFaddin Beach Bever, Michael R. and David J. Meltzer Driver, David Hester, T. R., F. Asaro, F. Stross and B. Giauque Hester, Thomas R., Michael B. Collins, Dee Ann Story, Ellen S. Turner, Paul Tanner, Kenneth M. Brown, Larry D. Banks, Dennis Stanford, and Russell J. Long Long, Russell J. 1986 Two Clovis Points From McFaddin Beach, Texas. Ohio Archaeologist 26(1):9. Patterson, Leland W. Pearson, Charles E., David B. Kelley, Richard A. Weinstein, and Sherwood M. Gagliano Pearson, Charles E., George J. Castille and Richard A. Weinstein Pearson, Charles E., and Richard A. Weinstein Russell, Jeffrey D. Shelley, Steven D. Stright, Melanie J., Eileen M. Lear, and James F. Bennett Tanner, Paul and Ellen S. Turner Turner, Ellen S. and Paul Tanner LinksMatthew White Photography http://www.matthewwhitestudio.com/ |

|