Back

Upper Dry Frio Through Time

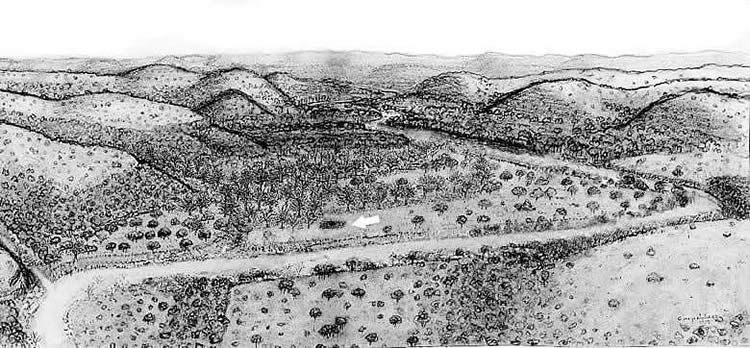

This series of drawings (below) by artist George S. Nelson shows how a small section of the upper valley of the Dry Frio River changed through time. Although these drawings are speculative reconstructions, artist’s impressions, they are informed by Gustavson’s geoarcheological study and the artist’s intimate familiarity with the area. George Nelson grew up on the banks of the Dry Frio not far downstream from these scenes near the small community of Regan Wells. Use the arrow keys to follow the landscape through time. The view remains more or less constant – you are looking upstream within the upper part of the narrow Dry Frio valley within the Western Balcones Canyonlands that flank the southern Edwards Plateau between San Antonio and Bracketville.

[Unfortunately, these drawings were inadvertently mixed up during the printing process and did not appear in correct order in the site report. Download PDF file with corrected figures LINK: Corrected Drawings, Woodrow Heard Report. PDF ]

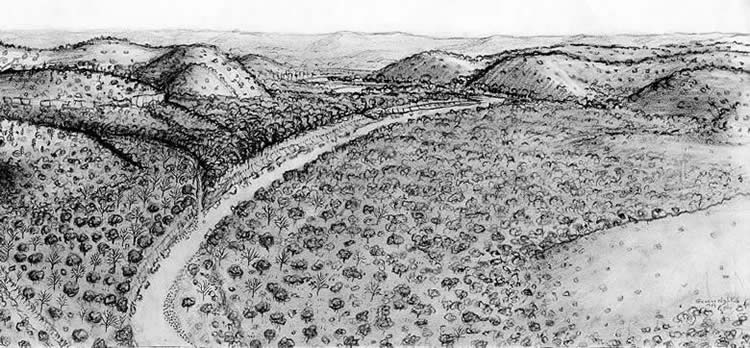

During the Late Pleistocene (end of the last Ice Age), perhaps 15,000 years ago, the Dry Frio flowed vigorously and the valley was heavily wooded. The climate was noticeably cooler and wetter than it is today. On the hills were stands of pinon pines, remnant stands of trees adapted to cooler climates. Roaming the area were remnant populations of various “megafauna” (big animals) such as wooly mammoths, camels, and a big bison species. These animals were becoming less and less common, the victims of long-term climatic changes toward drier and warmer conditions.

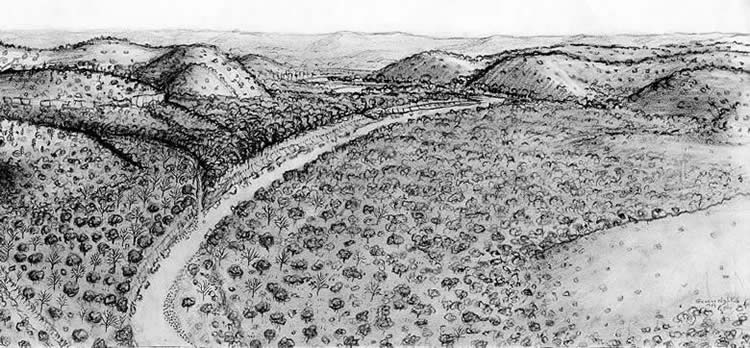

At the very end of the Late Pleistocene, about 13,200 years ago, the region experienced several centuries of drier conditions sometimes called the “Clovis Drought.” The drier and hotter conditions led to more plants and animals that tolerated drier conditions and fewer than preferred a cooler and wetter climate. The Ice Age megafauna became extinct, victims mainly of climatic change, but some were killed by Clovis peoples. The remnant stands of pinions shrank. The valley was still wooded, but not as thickly. Near the upper center of the scene a landscape scar is visible parallel and to the left of the river. This marks an older, abandoned channel – the river has swung to the right. Notice the large gravel bars – these were deposited during major flood events. Ironically, floods are often more damaging during droughts because there is less vegetation to prevent erosion.

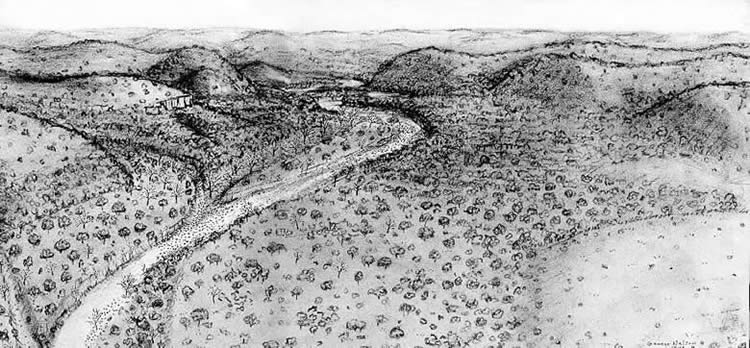

About 7500 B.C. (9,500 years ago) prehistoric groups began spending more time in this stretch of the Dry Frio. They camped at the place we know today as the Woodrow Heard site and left behind traces of daily life including Angostura dart points. In this scene, the area they camped is along the far side of the river near the center of the picture. Notice that there are now two parallel scars marking abandoned river channels. The river has continued to swing to the right.

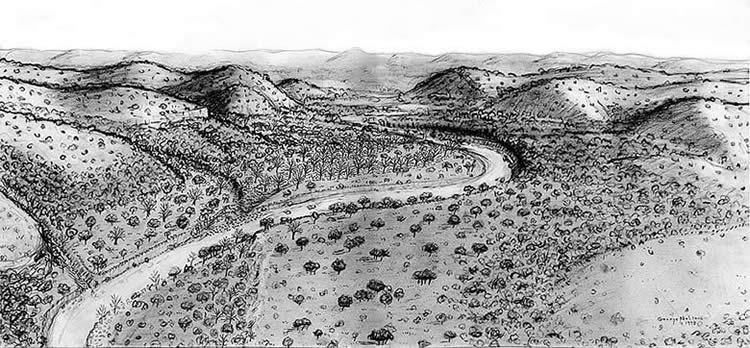

About 600 B.C. (2600 years ago) the Woodrow Heard site was a frequent stopping place for hunting and gathering groups frequenting the upper valley of the Dry Frio. The white arrow points to a spot that prehistoric cooks often used for baking plants, leaving behind a mound of discarded cooking stones (burned rocks), ashes, and organic waste. Today archeologists call these distinctive mounds “burned rock middens.” Notice that the river has continued to migrate and that the old abandoned channels stretching across the floodplain are lined with large trees – elms, pecans, and oaks. The old channels still hold water during floods and they are filled in with deep sediments, supporting the root systems of large trees. Indians camped under the trees and took advantage of the different kinds of resources present in the area.

Back