Leanne's Burial

Some 11,000 years ago, near the present town of Leander, Texas, the body of a young woman was gently laid in a shallow grave near a small stream. Whoever buried her had first carefully prepared the spot by digging out an oval depression in the hard, compacted soil, perhaps using a sharpened wooden stick. They placed her body on its side in a flexed position, with knees drawn up, arms crossed, and right hand resting beneath her head. Next to her side, they laid a heavily worn sandstone tool—a handstone, or mano—used first for grinding food and later for chopping. Last, they placed a limestone slab over the burial, perhaps to secure a hide wrapping around the body, or to mark the grave.

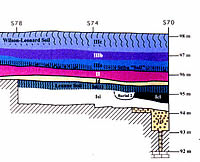

Rapidly covered over by sediment, the burial lay virtually undisturbed over the millennia, although scores of other hunting and gathering groups camped over and over again above her resting place. In 1982, archeologists from the Texas Department of Transportation uncovered the site (dubbed Wilson-Leonard after the landowners) during research in advance of highway construction, and the saga of the ancient Paleoindian woman continued.

Speaking to us through the ages, the woman—known variously as the “Leanderthal Lady,” or simply, Leanne, (for the nearby community of Leander, Texas)—had a powerful story to tell. Although she was young at the time of death by today’s standards—somewhere between 18 to 25 years of age—she was middle-aged by the standards of her day. There was no sign of disease or health problems other than tooth decay. We do not know why she died.

Dated to 9,000 B.C. (9500 radiocarbon years B.P.), the burial is one of the oldest and most complete human skeletons in North America. Leanne’s careful burial is considered one of several indications at the Wilson-Leonard site of an ongoing cultural transition from mobile, widespread Paleoindian lifeways to more entrenched, localized Archaic lifeways.

Read more about the Wilson-Leonard site.