|

In this section:

|

Mattie Hancock, one of five children

of Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock. Photo courtesy of Lillian

Robinson.

|

|

Rubin Hancock and his brothers were landowners at

a time when many others—Whites and African-Americans

alike—were sharecroppers and tenants.

|

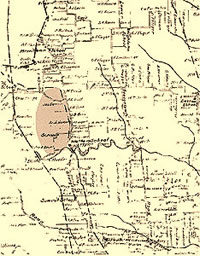

Map of roads in north-central Travis

County, 1898-1902, retraced in 1915, showing schools

and land owners (Project area, including Rubin Hancock

farmstead, is shaded). Courtesy of the Austin History

Center.

|

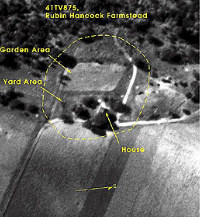

Aerial photo of farmstead site, 1937.

Corner of house is visible within grove of trees.

|

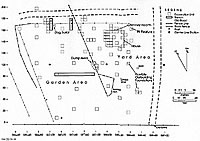

Layout of the Rubin Hancock farmstead,

as reconstructed by archeologists from TxDOT and Prewitt

and Associates.

|

|

All was created by a group of people who had just

come out of the bonds of slavery. Freedom was sweet

and they made the most of it.

|

Buttons and button hook from the

farmstead. a, shell; b, metal; c, porcelain (center

button is transfer-printed in calico design); d, glass;

e, button hook.

|

Close-up view of porcelain cup-plate

with hand-painted design.

|

|

In an area now overrun

by the busy interchange of Loop 1 and Parmer Lane in north

Austin lie the remnants of what was once a thriving community

of freed African-American slaves. Prominent in that community

were Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock who, after emancipation,

bought land, established a farm, and raised a family. Their

story—and that of their descendents and neighbors—has

been brought to life through archeological and historical

investigations.

Rubin Hancock, his wife, Elizabeth, and many

of their family members, were slaves of the prominent Austin

judge, John Hancock. Little is known for certain about their

early life, other than that they were all born into slavery—Rubin

in Alabama and Elizabeth in Tennessee—during the 1840s.

Although Texas did not recognize slave marriages (which otherwise

would have resulted in written records), it is known that

the two were married, or committed as life partners, before

they gained their freedom. More is known about the life and

philosophies of the judge. Despite his reliance on slavery,

Judge Hancock was adamantly opposed to Texas' secession from

the Union. After being elected to the state legislature in

1860 as a Unionist, he was removed from office when he refused

to swear allegiance to the Confederacy.

The1860 Census entry for Judge Hancock notes

his ownership of 15 slaves. Although none were individually

listed, it is likely that Rubin Hancock and his brothers Orange,

Salem, and Peyton were among them at that time. It is also

likely, according to family histories, that the four men were

half-brothers of the judge. Their considerable duties would

have included clearing land, planting, and working a 300-acre

dairy farm; maintaining cattle and other livestock on the

judge's extensive ranch lands; and building a variety of structures.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 brought emancipation

for slaves, announced in Texas on June 19, 1865. Sometime

after that, Rubin and his three brothers bought land in the

area north of Austin, making them landowners at a time when

many others—Whites and African-Americans alike—were

sharecroppers and tenants. With few resources available beyond

their own strength and determination— and the possible

assistance of Rubin's former master, the judge—Rubin

and Elizabeth Hancock established a productive farm, raised

a family of five children, and helped establish a small but

stable community of African-American farmers.

Known as Duval, the community was bound by family

ties and a strong church, St. Stephen's Missionary Baptist,

in which social gatherings, school classes for African-American

children, and worship services were held. The coming of the

A&NW railroad through the Hancock farm in 1881 meant an

influx of families into the area and the new recreational

resort of Summers Grove (later Waters Park). It also provided

a means of transport for farm products, such as cotton from

Rubin Hancock's fields, to nearby markets.

Life on the Farm

Rubin Hancock's granddaughter, Mable Walker

Newton, remembered visiting the farm as a child when Rubin

was in his later years. She described his home as a comfortable

house of logs and lumber siding with two rooms under the main

roof. The kitchen was a shed-type addition under a separate

roof. One room was the living room, where the fireplace was

located. Newton remembered that both rooms had big windows

with glass and wooden shutters that could be closed over them.

As was the case for many farm families of the

time, life was difficult, with seemingly unending chores for

adults and children alike. There was no running water or electricity;

water was hauled from a well, and all cooking was done on

a cast iron wood stove, for which wood had to be chopped each

day. Kerosene lanterns provided lighting for the small house.

The family raised cows and pigs, grew cotton and corn, and

maintained a large vegetable garden and fruit trees. Surplus

was sold to local store owners or sold in Austin.

According to family stories, the children found

entertainment by playing baseball, marbles, and dominoes using

handmade pieces made of cardboard. On Sundays, they attended

Sunday school and church picnics at St. Paul's Baptist Church.

Evenings often were filled with singing and socials with neighboring

friends and relatives.

Elizabeth Hancock died in 1899. Rubin Hancock

lived and continued to work the farm until well into his sixties,

leaving finally to live with his daughter, Susie, until his

death in 1916. The three surviving children, all daughters,

kept the farm until 1942, when the house was moved off the

site.

Weaving the Story

Little remains today of the small communities that once dotted

the landscape in north Austin, save for a few street signs

bearing some of their names. Over the past 100 years, northwest

Travis county has changed from a rural area to one of the

fastest-growing urban areas in the United States. When a highway

extension was planned in the area of Duval Road and Loop 1

(Mo Pac), archeologists from the Texas Department of Transportation

(TxDOT) surveyed the area for evidence of significant cultural

remains. They also examined old maps and records, and it was

through these means that they learned of the Hancock farmstead.

Using an aerial photo from 1937, TxDOT archeologist John Clark

was able to pinpoint the location of the farm and begin investigations.

On the surface, there was little evidence of

its existence, save for a well, chimney hearth, sections of

fences, and low stone walls. Excavations helped locate possible

stone piers of the house, trash areas, animal pens, and scatters

of artifacts, giving archeologists a better idea of the original

farmstead layout and patterns of day-to-day life. One of the

more poignant finds was the skeleton of a dog—likely

a family pet—carefully placed in a shallow grave.

Although more than 9000 artifacts were uncovered,

most were fragmentary. Nonetheless, careful analysis of the

many shards of glass, pottery fragments, and metal objects

revealed much about the family, their day-to-day life, and

their purchasing habits and tastes.

As Prewitt and Associates historical archeologist

Marie E. Blake analyzed artifacts and other archeological

data, historian Terri Myers set about to research family history.

Family members shared recollections and faded photographs.

Former neighbors were interviewed, and church records and

other documents were tracked down.

In a final analysis in which all archival, oral,

and archeological evidence was weighed together, several defining

characteristics of the Hancock family and farm become clear.

The family members put forth a great deal of effort to achieve

a level of equality and success, acquiring for themselves

through their own hard work a comfortable life complete with

both the necessities and some of the trappings of genteel

respectability. All of the Hancock brothers were able to own

and work their own farms. Each registered to vote and each

married and raised a family—members of which still prosper

in the Austin area. All was created by the will and effort

of a group of people who had just come out of the bonds of

slavery. Freedom was sweet and they made the most of it.

Afterward

Since the time of excavations at the Rubin Hancock site, a comprehensive suite of investigations has been conducted at the Moore-Hancock farmstead in Austin, where Rubin Hancock and his brothers lived and were enslaved to Judge John Hancock. Current landowners Michael and Karen Collins were uniquely suited to overseeing the investigation process: Mike is an archeologist with the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin, and Karen is an historian. Through their efforts, the story of Judge Hancock's farmstead and the families who lived in what is now the Rosedale area of Austin have been brought to life. During the process, numerous descendants of the Hancock family, including former slaves, were contacted, and they attended the dedication ceremony for an historical marker at the site.

Credits

The account of investigations, artifact analyses,

and the history of the Rubin Hancock farmstead was adapted

from After Slavery: The Rubin Hancock Farmstead, 1880-1916

by Marie E. Blake, and Terri Myers. TBH Co-Editor Susan Dial created the exhibit in 2001 and contributed to the writing.

Blake was a staff historical

archeologist for Prewitt and Associates, Inc., at the time of this report. Her current

work includes project management, archival research, archeological

investigations, and oral history projects throughout the state.

Myers is a historic preservation consultant who, at the time

of the project, was a partner with Hardy, Heck, Moore, and

Myers, Inc. Today she heads her own company, Preservation

Central, and pursues her research interests in African American

history, South Texas architecture and history, and rural historic

properties.

Archeological investigations in the field were

carried out in 1987 by the Texas Department of Transportation,

under the direction of John Clark, Jr., who also did extensive

archival research and oral history interviews.

Lesson Plan

A five-day lesson plan based on the archeology and history

of the Rubin Hancock farmstead was developed in 1999 by Dr.

Mary S. Black of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction

at UT-Austin. Lessons focus on tracing family history, utilizing

archival resources, map-making and map analysis, analyzing

artifacts, and doing archeology. http://www.dot.state.tx.us/env/education/rhfarm.pdf/

Print Source

Blake, Marie E. and Terri Myers

1999 After Slavery: The Rubin Hancock Farmstead, 1880-1916,

Travis County, Texas. Reports of Investigations No. 124, Prewitt

and Associates, Inc.; Archeology Studies Program Report 19,

Texas Department of Transportation, Environmental Affairs

Division.

|

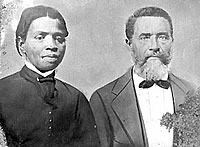

Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock were

among the first generation of freed slaves to purchase

and farm their own land in Travis County after the Civil

War. Photograph, likely taken sometime between 1889

and 1899, provided courtesy of Lillian Robinson.

Click images to enlarge

|

One of the properties owned by Judge

John Hancock after 1866, shown as it appears today.

Rubin Hancock, his three brothers, and other family

members were slaves of Judge Hancock prior to their

emancipation. The property, today known as the Moore-Hancock

farmstead, was excavated by members of the Travis County

Archeological Society under the direction of current

owners, Dr. Michael Collins and Karen Collins. Photo

courtesy of Michael and Karen Collins.

|

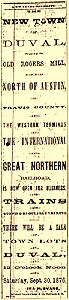

Newspaper advertisement for the

sale of lots in Duval, as promoted by one of the early

railroads in the area. The town never developed as

intended, perhaps overshadowed by activity in Round

Rock.

|

|

Section of 1910 USGS map of north-central

Austin showing the location of the Hancock farm (41TV875),

Duval, Waters Park, and other communities.

|

Skeleton of a dog, perhaps buried

by members of the Rubin Hancock family, found during

TxDOT investigations of the farmstead.

|

Color view of selected artifacts

found during investigations at the Rubin Hancock farmstead.

|

Artifacts found at the farmstead

indicated that the Hancock family enjoyed some of the

finer things in life; these items may have been purchased

in Austin or by mail-order catalog. From top, (l-r)

porcelain cup-plate, bottle stopper, buckle, marble,

proprietary medicine bottle, sewing scissors, escutcheon

plate, gold-plated pendant, buttons, clock gear, clock

key, table fork.

|

|