Early Ranching on the Northern Frontier of New Spain

Although wild cattle had drifted northward from ranchos in central Mexico since the 1500s, cattle ranching in South Texas began in 1749, when José de Escandón, the governor of Nuevo Leon, brought 3,000 settlers and 146 soldiers to settle the area bordering the Rio Bravo (now known as the Rio Grande river). This area, the northernmost stretch of the province of Nuevo Santander, had not been inhabited by the Spanish, although expeditions had travelled across portions of it on several occasions.

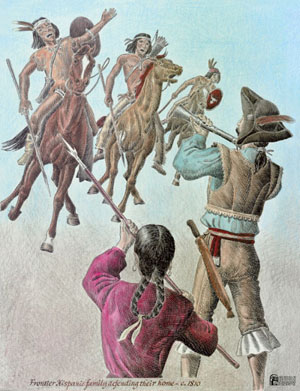

These early ranchos on the Rio Grande were established at a price: among many other hardships, the settlers had to forge a new life on the frontier under constant threat of attack by hostile Indians. In spite of this, ranching on the border was a success, with some of Texas’ most treasured traditions emerging from that early Spanish heritage.

The first settlers came from ranching communities in Queretaro, Nuevo Leon, and Coahuila, where they had already learned how to live and raise cattle successfully in those arid regions. These small settlements, or villas, along the Rio Grande, together with the vast ranches supplying the missions near San Antonio and Goliad, were the birthplace of the American cattle industry. Some of these Rio Grande ranches grew into settlements, becoming towns and cities. On this far-south stretch of the river, Captain Blás María de la Garza Falcón, already a wealthy rancher, received a land grant totaling 433,500 acres across the Rio Grande from Camargo. He established the ranch of Carnestolendas with 15 families on the north side of the river in 1752. The headquarters would later be called "Rancho Davis" and in 1848 would become Rio Grande City.

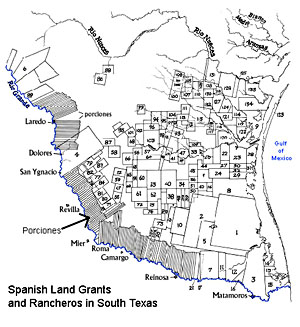

The first land grants were laid out in porciónes, long thin strips of land beginning at the river and

stretching inland (on both sides of the Rio Grande). This odd configuration assured water for each landowner. Ranchers moving

into the arid brush country beyond the porciónes needed and received very large land grants to support

their cattle.

To build a presa, workers collected earth from the front of the dam and carried it in rawhide containers to the top, where they emptied the containers. Draft animals walking back and forth packed the earth down to make the dam. A spillway made of sillares (caliche blocks) completed the project. This type of dam and reservoir was built at El Randado in Jim Hogg County during the 1830s. More common was the noria con buque. Laborers dug the well with tools made by blacksmiths. The noria, which could be either circular or rectangular, was lined with hand-quarried sillares. Two walls were built up on either side to support a mesquite log placed horizontally above the well. A long rope was placed over the log, with one end tied to a rawhide bucket and the other to an ox or mule. The draft animal pulled on the rope to raise the bucket and reversed to lower it. Often a large holding tank, made of sillares and covered with lime plaster, was built adjacent to the well.

The ranchers brought with them other Spanish traditions. They organized their landholdings as haciendas. A hacienda engaged in any money-making business: lumber, sheep, mining, farming, etc. However, the further north from central Mexico the haciendas spread, the more they became limited to cattle raising and the larger they grew in order to support the herds. Over time, the hacienda became an enclosed community, a feudal estate, whose workers and their families were answerable only to the hacendado or patron (ranch owner). The landowners provided food, clothing, shelter, and religious instruction to the native Indian or mestizo (mixed Indian and Spaniard), who provided their labor. The hacendado and his family lived in a large house made of sillar blocks quarried on the property. Most early ranch complexes often were surrounded by stone walls for security or had other defensive fortifications. The casa mayor (main house) had troneras (gunports) built into the walls and served as a fort during the frequent attacks from Comanche and Lipan Apache Indians.

The vaqueros and hacienda laborers and their families lived in one-room huts, or jacales. A jacal was made of mesquite poles placed upright, supported by forked horcones (corner posts). Limbs were placed horizontally across the poles, and mud or adobe filled the openings between the limbs. Forked poles centered on the end walls supported the ridgepole beneath the thatched roof. Women cooked in a grass or corn stalk ramada (arbor) near the jacal, and the family ate outdoors. A few goats or chickens lived in a pen; corn, beans, and pumpkins grew in a garden near the house.

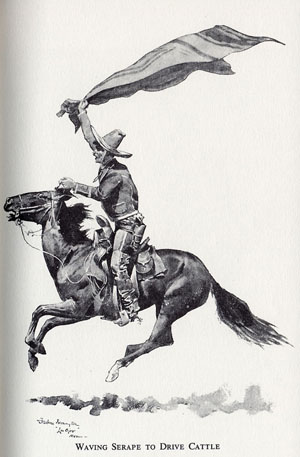

Most traces of the Spanish Colonial cattle days—ruins of ranch structures, stone walls, and wells—on the Rio Grande are on private property. There are a few sites, such as those at San Isidro and San Ignacio, which can be seen by the public. A 19th-century jacal still stands at Los Saenz, near Rio Grande City, where it can be viewed from the street. Even without a physical presence, however, the Spanish Colonial ranching traditions still remain strong. They have pervaded our culture and remain in the form of language and music, clothing, saddles, tools, round-ups and rodeos, cattle drives, and the mythic image of the American cowboy.

To learn more about Nuevo Santander and early ranches on the

Rio Grande see

www.TexasBeyondHistory.net/

falcon/index.html

Credits and Sources

This section was contributed by Karen Gerhardt Fort and Tom Fort from Edinburg, Texas. Karen is an independent historian and author, and Tom is a historian on staff with the Museum of South Texas History.

Print Sources

Cabeza de Vaca, Alvar Nuñez

1993 The Account: Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca's Relación. An Annotated Translation by Martin A. Favata and José B. Fernandez. Arte Publico Press, Houston, Texas.

Cavazos Garza, Israel

1994 Nuevo Leon y la Colonización del Nuevo Santander. Programa Editorial de la Sectión 21 del Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación. Monterrey, N.L., Mexico.

Cortés, José

1989 Lieutenant in the Royal Corps of Engineers, 1799. Edited by Elizabeth A. H. John. Translated by John Wheat. In Views from the Apache Frontier: Report on the Northern Provinces of New Spain. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London.

Graham, Joe S.

1994 El Rancho in South Texas: Continuity and Change from 1750. University of North Texas Press, John E. Conner Museum, Texas A & M University–Kingsville. Denton, Texas.

Jordan, Terry G.

1981 Trails to Texas: Southern Roots of Western Cattle Ranching. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London.

Lea, Tom

1957 The King Ranch. 2 vols. Little, Brown and Company, Boston.

Sánchez, Mario L.

1994 A Shared Experience: The History, Architecture and Historic Designations of the Lower Rio Grande Heritage Corridor. Second Edition. Los Caminos del Rio Heritage Project and the Texas Historical Commission, Austin.

Links

Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Vazquez Borrego, Jose http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/

online/articles/VV/fva43.html

A Shared Experience online http://www.rice.edu/armadillo/

Past/Book/index.html

Adapted from the print version by Los Caminos del Rio Heritage Project

and the Texas Historical Commission

[Austin, Texas, 1994]

The History, Architecture and Historic Designations

of the Lower Rio Grande Heritage Corridor

Visit the Museum of South Texas History to learn more about the heritage of the lower Rio Grande. http://www.mosthistory.org/

|

|

|

|

|

|