Padre Canyon

The Padre Canyon, or Samalayuca, project encountered numerous prehistoric sites but is particularly significant for the discovery of two Paleoindian sites, a very rare occurrence in the Trans-Pecos region. The sites (41HZ504 and 41HZ505) contain evidence of the Folsom culture, which immediately follows the Clovis culture—the earliest known culture in the Trans-Pecos.

Located in what is today a sparsely vegetated area on the western edge of Hudspeth County, the Padre Canyon Folsom sites lie on a gradually southern-sloping Quaternary fan on the southern terminus of the Hueco Mountains. The Padre Canyon arroyo runs some 200 meters (roughly 650 feet) southeast of the site. Today this area is part of the Chihuahua Desert, but during Folsom times (8,950 to 8,250 B.C.) it would have been a grassland or savannah bordered by mixed forest in the lower elevations and spruce, fir, and pine forest in the uplands. Water would have flowed through the Padre Canyon arroyo, and springs, streams, and playa lakes would have provided abundant surface water for prehistoric visitors.

Although evidence from these sites was partially derived from surface collection and disturbed contexts, it is nonetheless important to our understanding of this early time. The Paleoindian period is the most poorly known archeological period in the Trans-Pecos. No chronometric dates have been reported from contexts clearly associated with Paleoindian materials. Recognition of Paleoindian sites and materials chiefly has been accomplished through cross-dating distinctively fluted lanceolate projectile point forms with those found at chronometrically dated sites in adjacent regions.

One reason for the paucity of Paleoindian sites in the Trans-Pecos is that they may not be recognized in components lacking diagnostic projectile points. This problem is exacerbated by artifact collectors who pluck projectile points from Paleoindian lithic scatters, rendering them unidentifiable to surveyors. In addition, many Paleoindian sites may have been deeply buried by alluvial deposits and go undetected during surface survey. Of the Paleoindian sites in the region that are known, many are severely eroded and heavily disturbed, meaning that Paleoindian materials are often mixed with artifacts deposited during later occupations.

Padre Canyon was discovered in 1992 by Mariah Associates, Inc. during a cultural resources survey of the area to be affected by the proposed Samalayuca Pipeline of the El Paso Natural Gas Company (EPNG). Though initially recorded as two sites, they were subsequently determined to form a single continuous scatter of materials on the same geomorphic landform and are now considered to be a single site. After conducting shovel tests, Mariah recommended that further testing be conducted in order to determine the nature and significance of the site.

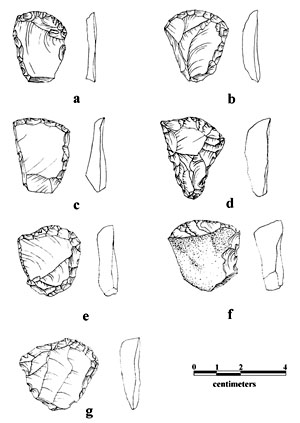

Mariah returned to Padre Canyon in May of 1994 to conduct a surface collection, a geomorphological study, limited subsurface testing, and mapping. They recovered 246 unmodified flakes, 23 scrapers, three edge-modified flakes, 4 Folsom points, 1 Midland point, 6 bifaces, 23 scrapers, 6 cores, 3 unifaces, and 4 El Paso Brown ceramic sherds. Based on the assemblage, Mariah concluded that Padre Canyon was primarily a Folsom site with some Late Prehistoric “background noise.” They did not recommend it for further testing, however, because they determined that various post-depositional processes had removed the assemblage from its primary context and transported it to its current location, atop Late Holocene deposits.

Despite Mariah’s assessment, the Texas Historical Commission (THC) and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) recommended additional testing to clarify the character of the archeological deposits at Padre Canyon. The EPNG contracted Centro de Investigaciones Arqueologicas (CIA) to perform the testing. In late 1996 and early 1997, CIA conducted surface collection, subsurface testing, additional mapping, and screening of animal burrow spoil piles to evaluate the site’s integrity. They recovered 514 unmodified flakes, 18 utilized flakes, and 6 cores. CIA determined that the assemblage had been extensively turbated by badger burrowing, compromising its vertical integrity. They recommended that data recovery excavations be conducted to determine whether any horizontal integrity remained.

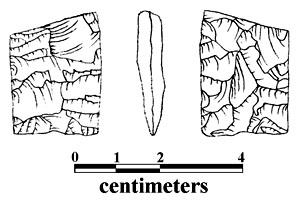

In July and early August of 1997, CIA excavated the part of Padre Canyon in the proposed pipeline’s right-of-way. The excavation yielded a total of 8,671 lithic artifacts, including 8,531 unmodified flakes, 26 scrapers, 88 edge-modified flakes, 20 cores, 2 biface fragments, 1 possible ground stone fragment, 2 Midland point fragments, and 1 Folsom point fragment. No faunal specimens were recovered and the only floral specimen that could be identified was charred mesquite wood taken from a hearth feature. CIA confirmed the occurrence of bioturbation at the site and also found that some downslope movement of the assemblage had occurred. Upon completion of the excavations, CIA initiated analyses of artifacts, features and special samples, but for various reasons was unable to fulfill reporting and analysis obligations.

In December of 2000, EPNG contracted SWCA Environmental Consultants to complete the analysis and produce a final report of CIA’s data recovery excavations. This work is still in progress.

Though the integrity of Padre Canyon’s Folsom deposits has been compromised by bioturbation and downslope movement, its assemblage is fairly complete and can be addressed and evaluated essentially as a surface collection. This assemblage is all that is available to extrapolate information about how the inhabitants of the site lived. Padre Canyon’s projectile points and bifaces are made of high quality orthoquartzite and chert that comes from an unidentified source outside of the Trans-Pecos, while the rest of its assemblage comes from local low-quality stones. In addition, its assemblage is largely made of discarded informal tools and the debitage that resulted from manufacturing them. This suggests that the inhabitants of the site were highly mobile and carried a small formal tool kit that utilized high quality stone, but took advantage of low-quality local stone to manufacture expedient informal tools that could be discarded after use. Based on the assemblage in general, the site served as a residential or base camp for a group of Folsom people who engaged in retooling, hide-working, and various domestic activities.

Contributed by Kevin Miller and Carly Whelan.

Sources

Mauldin, Raymond and Jeff D. Leach

1997 The Padre Canyon Paleoindian Locality, Hueco Bolson, Texas. Current Research in the Pleistocene 14:55-57.

Kevin A. Miller, Kerri S. Barile, Steve Carpenter, Doug Drake, Ken Lawrence, and Brandon Young

n.d. Archaeological Data Recovery at Four Sites on the Samalayuca Natural Gas Pipeline, El Paso and Hudspeth Counties, Texas. SWCA Environmental Consultants, Austin.

Miller, Myles R. and Nancy A. Kenmotsu

2004 Prehistory of the Jornada Mogollon and Eastern Trans-Pecos Regions of West Texas. In: The Prehistory of Texas, edited by Timothy K. Perttula, pp. 205-265. Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

| Though the integrity of Padre Canyon’s Folsom deposits has been compromised by bioturbation and downslope movement, its assemblage is fairly complete and can be addressed and evaluated essentially as a surface collection. |

|

|

|