Salt Trade, Trails, and Wars

Few would believe that the desert surrounding El Paso contains a resource so valuable that people would travel hundreds of miles to utilize it and that two wars would be fought over access to it. Salt is taken for granted today, but for much of human history, it was taxed, monopolized, regulated, fought over, and even used as a medium of exchange. As the oldest and most continuously produced mineral in the state, it overshadows the Texas oil industry.

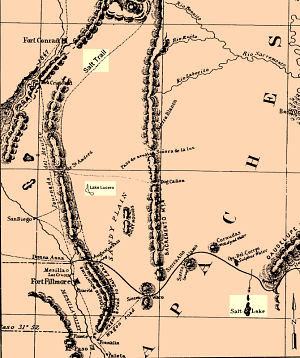

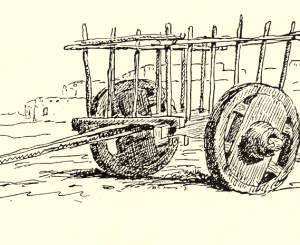

Carts, wagons, and, later on, trucks, transported loads of this mineral along trails and roads through the rugged Chihuahuan desert in the northwestern Trans-Pecos region. Routes from the salt lakes and salinas, or natural mineral deposits, connected the Salt Flats west of the Guadalupe Mountains with San Elizario. Another historically known salt trail extended from El Paso northward into New Mexico. In recent years, archeologists have discovered remnants of these trails, historic routes of commerce over which this important mineral was carried.

Why Salt Is Important

Salt is 39 percent sodium, a chemical element that is necessary for survival. Sodium controls blood volume, muscle contractions, the transmission of electrical nerve impulses, the contraction of blood vessels in response to nervous stimulation or hormones, the absorption of glucose, and the transport of glucose and other nutrients across membranes, especially the intestine. Humans obtain the salt they need primarily from meat and secondarily from plants and water. But these sources do not always provide the body with enough salt, forcing humans to seek it elsewhere.

Salt also has uses for humans other than physiological ones. Before the advent of refrigeration, salt was used to cure and preserve meat. Because herbivorous (plant-eating) animals are attracted to salt licks and salt springs, Native Americans often lay in ambush at such places or created artificial salt licks to lure the animals. In colonial New Spain, salt was necessary for treating leather, stabilizing dyes, and, above all, mining silver.

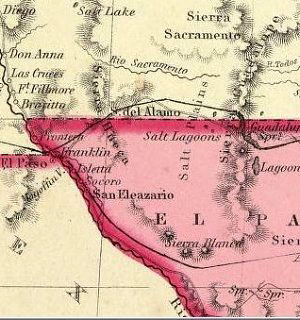

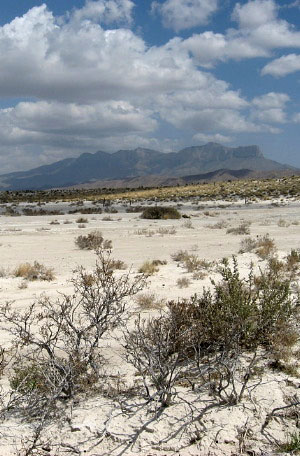

The salt deposits of western Texas and southern New Mexico are remnants of ancient seas that have dried up. The remaining salt has percolated up through the ancient sea bed and dried on the surface, making a salt crust that, before intensive mining, was several feet thick in some areas. These salinas are concentrated at Lake Lucero, 186 kilometers (116 miles) north of El Paso in the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico, and at the base of the Guadalupe Mountains, west of El Paso. The salt they provided was an essential resource for the native people of the area, who visited them for thousands of years. Salt may have even been exchanged throughout the Jornado Mogollon region, perhaps as far away as Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, Mexico. When the Spanish arrived, salt from the salinas became essential both for the operation of the silver mines in Parral and for the survival of the Spanish citizens and Native Americans of the El Paso area.

Historic Conflicts

In 1647, Diego Romo de Vivar petitioned the governor of Nueva Vizcaya for permission to exploit a salina in the Guadalupe Mountains. Diego de Vargas, governor and captain general of Nuevo México, discovered additional salinas in the Guadalupe Mountains in 1692 and reported that their salt crusts were so thick that they had to be chipped away with a pick and that they re-formed within a few days of being removed, so that the salt could be continually mined. It is not clear from their records when the salinas of Lake Lucero were discovered by the Spanish, but the silver miners of Parral were exploiting them by 1709 and perhaps as early as 1657. The salinas of Lake Lucero and the Guadalupe Mountains were used initially by the silver miners of Parral, but by the 18th century the people of the El Paso area were using them, too. They undertook annual journeys to the salinas with soldiers, who protected them from attack by hostile Apache groups. The San Andres Salt Trail was established in 1824 to transport salt from the Lake Lucero salinas to communities in the Rio Grande valley south of El Paso.

In the mid-19th century, two conflicts arose over the political and economic jurisdiction of the salinas of the El Paso area. The roots of these conflicts, known as the Salt Wars, lie in the enduring historical threads of two great colonial empires, Spain and Britain, each with very different world views as codified in laws that governed rights to the salt. The Salt Wars occurred during the ebb and flow of historical influences as the political and cultural boundaries of the United States and Mexico, inheritors of the colonial legal systems, were being resolved. These conflicts reverberated far beyond the remote borderlands where they played out, and substantially contributed to the establishment of the modern geopolitical setting.

According to Spanish law, the title to all mines and minerals (including salt) belonged to the government, and the king had long ago granted the inhabitants of New Spain the right to freely gather it. When Texas, which initially included eastern New Mexico, became part of the United States in 1848, the law changed to British common law, which dictated that the title to minerals belonged to the owner of the land on which they sat. Several influential Texans took advantage of this turn of events and formed a partnership to exploit the salinas of Lake Lucero, which they thought could prove to be very lucrative. The partners obtained certificates to the land in 1850, shortly before Texas ceded eastern New Mexico to the federal government. Though the partners’ claim to Lake Lucero was questionable at best, they were anxious to make a profit and subleased the land to James W. Magoffin in 1852.

Magoffin attempted to levy a fee for gathering salt at the salinas of Lake Lucero, but had trouble enforcing it. In January of 1854, he received a tip that a large group of citizens from the village of Doña Ana, New Mexico was on its way to Lake Lucero to gather salt. Magoffin reported this to the sheriff who gathered a posse to confront them. When the two groups met a gun battle ensued, fatally injuring three New Mexicans and forcing all of them to abandon their animals and carts. New Mexico officials indicted Magoffin on a charge of unlawful assembly and assault with intent to kill and requested that he be extradited from Texas. Magoffin responded by surrendering the animals and carts to their rightful owners and making restitution for the damages he had caused. As a result, the territorial legislature of New Mexico passed an act nullifying the Texas partners’ land claim and guaranteeing the citizens of New Mexico the right to freely collect salt.

The San Elizario Salt War of 1877 resulted from a political situation that was similar to that of the Magoffin Salt War of 1854. In 1877, Judge Charles Howard filed a claim to 320 acres covering the primary salinas of the Guadalupe Mountains. He then closed the road that led to them and instituted fees for collecting salt. The citizens of San Elizario were outraged and insisted that they had a right to freely collect salt from the salinas. Howard intercepted a group of these citizens on their way to the salinas and precipitated a riot. Howard was jailed for his actions, but was released upon payment of $12,000 and fled to New Mexico. He returned a few weeks later and killed Louis Cardis, a popular leader of the group who claimed the right to gather salt, then fled again. Howard returned two months later with several associates and 20 Texas Rangers. In the ensuing battle, Howard and two associates were killed and the rangers were disarmed and expelled. In all, 12 men were killed and 20 were wounded.

Only a few short years after the people of the El Paso area had died trying to defend their right to freely gather salt during the San Elizario Salt War, the salinas of Lake Lucero and the Guadalupe Mountains fell into disuse. In 1881, the arrival of the railroad in El Paso meant that goods from all over the United States could be easily and cheaply shipped to the area. Cheap salt from Kansas put a temporary end to the ancient tradition of gathering salt from the salinas of the El Paso area. During the 1940s and 1950s, miners again dug for salt in the Guadalupe salinas, but irrigation on ranches in the area lowered the water table and diminished returns from the flats.

Surveys and Discovery

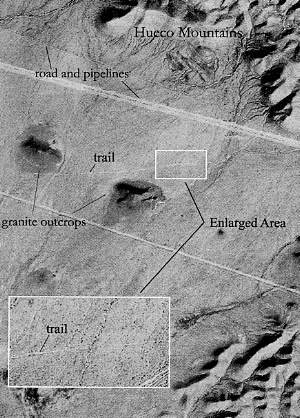

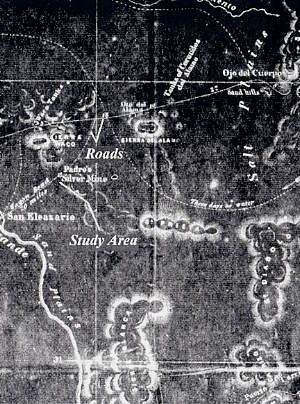

In January 2001, archeologists with the Texas General Land Office found traces of an old road in Hudspeth County while surveying a 40-acre tract south of the Hueco Mountains. Visible over a 16-kilometer (10-mile) stretch, the road rested on thin soils atop a level substrate of white calcrete, a geological setting which favored its preservation. Using old maps and other historical sources, archeologist Steve Carpenter working with the General Land Office identified what appears to be the 1863 route from San Elizario to the Guadalupe salinas. The discovery of several artifacts, including tin cans dated to the latter part of the 19th century, indicated that the road was not a modern ranch road. Designated as 41HZ571, portions of this trail are denoted in Creuzbauer’s 1849 map drawn for Robert S. Neighbors. The road may have fallen into disuse after the Salt War of 1877.

Remnants of the San Andres Salt Trail also were identified along the North-South Freeway on the outskirts of El Paso, where a one kilometer (half-mile) stretch was visible as a series of deep, parallel ruts and braided drainage channel. This north-south stretch was recorded as 41EP2901.

A large section of Fort Bliss in El Paso County and Dona Ana County, New Mexico was surveyed in a further attempt to identify traces of the San Andres Salt Trail northward from El Paso. Although archeologists consulted various historic documents and maps, including an 1849 map of Capt. Randolph Marcy’s expedition showing the location of the Salt Trail, their efforts to identify it on the ground have not proven successful.

Visitors to the area can learn more about salt and the Salt Wars at the Los Portales Cultural Center in San Elizario. The center has an excellent display with historic photographs.

Contributed by May Schmidt, Carly Whelan, and Steve Carpenter.

Sources

Adshead, S.

1992 Salt and Civilization. St. Martin's Press, New York.

Burt, C., Christine G. Ward, David Kuehn, and Myles R. Miller.

2006 Archeological Testing of a Segment of the Historic San Andres Salt Trail (Texas State Archeological Landmark Site 41EP322/41EP2901 and the Eastern Margin of Prehistoric Site 41EP358, Northeast El Paso, El Paso County, Texas. Geo-Marine, Inc. (Report of Investigations 707EP)

Bentley, Mark T.

1991 Early Salt Mining in the Paso del Norte Region. The Artifact 29(2):43-55.

Carpenter, Stephen M.

2002 Search for the San Elizario Salt Road. The Journal of Big Bend Studies14: 141-162.

Download pdf

Hawthorne-Tagg, Lori, Deni J. Seymour, Robert J. Hall, Robert Martinez and Susan Ruth

1998 Traces of the Trails: The Spanish Salt Trail and Butterfield Trail on Fort Bliss, Doña Ana County New Mexico and El Paso County, Texas. Lone Mountain Archaeological Services Report 501 and Historic and Natural Resources Report 97-09, Cultural Researches Branch, U.S. Army Air Defense Artillery Center, Fort Bliss, Texas.

Links

“Salt Industry.” In Handbook of Texas Online www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/

articles/SS/dks1.html

“The El Paso Salt War” Website of National Park Service: Guadalupe Mountains National Park, History and Culture www.nps.gov/gumo/historyculture/saltwar.htm

“Salt War of 1877” by Silvia Rodriguez, Tonantzin de Aztlan and Elena Espinoza

In Borderlands: An El Paso Community College History Project

www.epcc.edu/nwlibrary/borderlands/

18_salt_war.htm