Big Bend Presidios

In 1775 the Spanish built two presidios near the apex or southernmost point of the “big bend” of the Rio Grande to fill in gaps in the long chain of forts that stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the California coast. The line of presidios was intended to help stabilize the volatile northern frontier of New Spain and protect Spanish citizens from mounted raids by the Apache and Comanche.

For ten years the two Big Bend presidios were home to small groups of Spanish soldiers, Indian scouts, and their families who eked out an unbelievably isolated and hardscrabble existence. The mounted soldiers patrolled 50-60 mile stretches of a particularly rugged part of the northern Chihuahuan Desert. While “off duty,” the soldiers and their families struggled to raise crops to feed themselves and their large horse herds. The nearby lands proved ill-suited for farming and the presidios soon proved too costly to maintain. They were abandoned by 1784 as the Spanish authorities decided to concentrate on protecting the most heavily settled areas, such as those along the Rio Conchos in southern Coahuila.

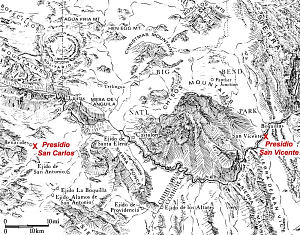

Presidio San Carlos is located some 64 kilometers (40 miles) downstream from La Junta de los Rios (near Presidio, Texas) in what is today the state of Chihuahua, near the town of Manuel Benavides. This presidio was built about 16 kilometers (10 miles) south of the Rio Grande on a small tributary stream. Presidio San Vicente was built on the river some 60 miles farther downstream (around the big bend) between Mariscal and Boquillas Canyons in what is today the state of Coahuila. The 18th century Spanish considered the Big Bend area to be Tierra Despoblado—uninhabited lands. Even today, it remains one of the most remote and little-settled regions of Texas and northern Mexico

During the first half of the 18th century, dissatisfaction grew among the citizens of the northern frontier of New Spain at what they viewed as the oppressive and neglectful attitudes of the European-based government. Increased raids from the north by Apache groups during this time made for an even more volatile situation that the Spanish government was forced to address by the middle of the century. In 1765, the king of Spain sent the Marqués de Rubí, a high ranking military officer, to New Spain to conduct an inspection of the northern frontier presidios and offer recommendations on how to improve the defensive system. Rubí suggested reorganizing the frontier by changing the location of some of the presidios and the regulations governing their construction and management.

The Spanish government accepted Rubí’s recommendations and made them the basis of the Regulations and Instructions of 1772, which reformed military regulations and made plans for a new line of defensive presidios along the northern frontier. Hugo O’Conor was appointed Commander-Inspector of the military forces of the northern frontier and given the task of implementing the changes. He had the presidios of Cerro Gordo (in southern Chihuahua) and San Sabá (near Menard, Texas) abandoned and chose locations along the Rio Grande for the new presidios of San Carlos and San Vicente. O’Conor returned to the sites in 1773 with military engineers who certified them as acceptable for the location of presidios. Soon thereafter, the troops from the abandoned presidios set up temporary quarters at the sites and began work on permanent buildings. Construction of the presidios was completed in 1775.

Each presidio was assigned 40 Spanish soldiers, two corporals, one sergeant, four officers, one chaplain, ten Indian scouts, 352 horses, and 51 mules. The soldiers and scouts lived in the presidio barracks with their families. The standard equipment for the soldiers was leather armor, a shield, a musket with case, two pistols, a sword, and a lance. Scouts were equipped with a bow with arrows, a pistol, a shield, and a lance. The duties of the soldiers and scouts included maintaining and guarding the presidio, escorting supply and merchant convoys and dispatch rides, guarding the livestock, and patrolling each presidio’s area of jurisdiction daily.

Life was very hard for the soldiers and scouts of the presidios. They often suffered from hunger, thirst, and lack of sleep and were forced to perform their duties in the most inclement weather with tattered uniforms, damaged weapons, and worn out horses. They worked long hours, leaving them with little time for their families or for instruction in reading, writing, religion, or military arts. Life at the San Carlos and San Vicente was made even harsher by the position of the presidios at the very end of the northern frontier supply line, and a harsh local climate that hindered farming efforts.

As a result of San Carlos and San Vicente’s continuing supply problems and poor performance in controlling hostile Indian movements, Commander-General Teodoro de Croix began to doubt the usefulness of the entire line of presidios established in 1772. He set forth a new policy wherein presidios would aid in the repopulation of abandoned frontier areas by helping encourage civilian settlement around them. Because of the poor farming potential of the areas around San Carlos and San Vicente and their great distance from supply centers, Croix determined that they were not appropriate for settlement and ordered their abandonment in 1780. The king approved the plan in 1782 and Croix removed the troops from the presidios, leaving a caretaker garrison of 10 men at each to maintain the buildings for future needs. The presidios were completely abandoned in 1784.

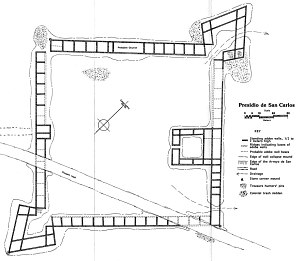

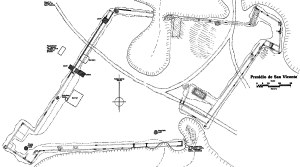

Because they were placed in an almost uninhabitable area of the frontier, San Carlos and San Vicente have survived almost undisturbed for over 200 years, beyond the loss of their roofs and upper walls. This, and the fact that they represent a very brief period of time, makes them extremely important archeological sites, but so far little investigation has been conducted. In 1953 Charlie Steen and Hal Broderick located the site of San Vicente and created a rough plan of its walls. In 1961 and 1969, Rex Gerald of the University of Texas at El Paso visited both presidios to conduct surface collections and make plan maps. In 1968 he published a study of the presidios that included their historical background and a map of San Carlos. In 1983, Joseph Sanchez of the Southwest Regional Office of the National Park Service (NPS) conducted archival research in Spain and found information on the 18th century defenses of northern New Spain pertaining to San Carlos and San Vicente.

The most extensive work at the sites was carried out by NPS archeologist James Ivey in 1984. With a small team, he surveyed the presidios and nearby modern features, cleaned the tops of the walls, identified areas that had been disturbed by treasure hunters, and created maps of the sites. Ivey published the results of their survey along with the maps and historical background of the presidios in 1990. San Carlos and San Vicente likely contain the best available archeological record of the engineering methods, architecture, and economics of typical frontier presidios after 1772, as well as the daily lives of the presidial soldiers, scouts, and their familes. Excavations are needed to unearth the wealth of information that they contain—mere fragments of discarded trash and bones that may speak volumes about life on the remote frontier of New Spain.

Contributed by Carly Whelan based on a report by James Ivey and other sources cited below.

Sources

Gerald, Rex

1968 Spanish Presidios of the Late Eighteenth Century in Northern New Spain. Museum of New Mexico Research Records 7, Museum of New Mexico Press, Sante Fe.

Ivey, James E.

1990 Presidios of the Big Bend Area. Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Paper 31, Division of History, Southwest Cultural Resources Center, National Park Service, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Available online: www.nps.gov/bibe/historyculture/upload/

presidios_bibe.pdf

Turpin, Solveig A. and Herbert H. Eling Jr.

2004 Aguaverde: A Forgotten Presidio of the Line, 1773-1781, The Journal of Big Bend Studies 16:83-128.