La Junta Foragers

This division into sedentary and semi-nomadic groups was naturally not a clear-cut one. The sedentary groups were addicted to hunting-trips into the mountains and probably even to the distant Texas Plains. The semi-nomads seem to have practiced a certain amount of agriculture; and there seem to have been still other groups that cannot be classified as one or the other, for they spent much of the year in Rio Grande settlements and the remainder roaming and hunting throughout the area and beyond its bounds.” (Kelley, Campbell and Lehmer 1940:16-17)

The above quote from the classic work of Big Bend archeology, The Association of Archaeological Materials with Geological Deposits in the Big Bend Region of Texas is the earliest published recognition that the region’s native cultural milieu was typified by a dual division in lifeways. Sedentary farmers lived along the Rio Grande and its tributaries, while nomadic foragers occupied the rest of the region. But the statement leaves this dual division anything but clear. We have sedentary groups “addicted” to foraging trips; we have “semi-nomads” practicing agriculture; and we have others that “cannot be classified as one or the other” because they consistently do both! From today’s perspective, it is entirely possible this seemingly confusing scenario of overlapping and fluid lifestyles may reflect native reality.

Early-to-mid-20th century archeologists tried to classify their materials into hard and fast categories and defined archeological “cultures” which were thought to represent prehistoric ethnic groups. Furthermore, the prevailing cultural evolutionary schemes of the day held that human groups could only get more complex through time. Foraging demanded a simple, mobile lifestyle, while the more involved (and, supposedly, evolved) practice of agriculture was strictly associated with sedentary peoples. Thus, the people living in villages near the Rio Grande were seen as one group, the mobile foragers of the mountains and intermontane basins were another, and the people who appeared to do both were another still.

This impression was largely based on early Spanish accounts, especially those having to do with La Junta de los Rios, where all three lifestyles are described, although not consistently. It is much more difficult to say with any degree of certainty that the same characterizations accurately depict prehistoric lifeways. Unfortunately, the passing of time has largely obliterated any defining measure of ethnicity for archeologically known cultures. Perhaps agriculture, foraging, mobility and sedentism were all part and parcel of a much more fluid subsistence adaptation intimately tied to the marginal ecological zones of the Chihuahuan Desert.

The La Junta phase (A.D. 1200–1450) has long been held to be representative of sedentary (or semi-sedentary) agricultural lifeways in the Big Bend. As detailed in the featured exhibit on La Junta, villagers living in pithouse communities along the Rio Grande and the Rio Conchos grew small plots of maize, beans and squash in low-lying floodplain fields. Wild game and plants were seen as supplementary to a diet reliant on domesticates. But, the same ethnohistoric data used to infer the presence of two or more divergent groups in the Big Bend can also be used to illuminate the workings of a much more complex way of life.

In 1747, the Spaniard Joseph de Ydoiaga visited numerous indigenous settlements in the La Junta area. The residents of El Mesquite and Puliques, two pueblos (as the Spanish referred to villages) in the area, told Ydoiaga that their agricultural crops were never very bountiful and were always in danger of being washed away by floods. It was also mentioned that two maize crops were planted per year. If one of these crops failed, there was insufficient food to last the year. The native solution to these perennial problems was to continue to forage for wild foods. Ydoiaga specifically mentions the use of pinyon nuts, javelinas, turkeys, prickly pear fruit and mescal (baked agave) for food at Puliques, and that deer, other game and plants were procured within 20 leagues (96 km) from the river settlements.

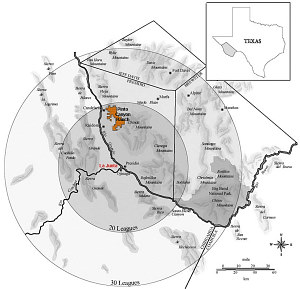

If we take the Spanish estimations as a guide, native La Juntans covered a large amount of space in pursuit of wild foods. Using the confluence of the two rivers as a center point, the 20 league radius extends to just below the foothills of the Davis Mountains (south of Marfa, TX) to the north, follows the Santiago Mountains on the east, skirts the town of Terlingua on the south, and takes in the same amount of space in Mexico, including most of the lower Conchos drainage. Widening the foraging radius to 30 leagues (144 miles) to account for Spanish accounts of the distance La Juntans traveled while hunting bison, covers virtually the entire Big Bend. The larger radius also helps account for the fact that La Junta villages extended 35-65 kilometers (22-40 miles) from the confluence.

The Spanish accounts do not say whether these foraging trips were solely prompted by crop failure, and it is more likely that they were undertaken seasonally. In a land of wildly fluctuating rainfall, scorching heat and the commensurate shortages of food, a dual subsistence strategy utilizing both agriculture and foraging together may have offered what total dependence on one or the other could not: stability. Groups were able to remain in settled villages at La Junta (at least for much of the time) precisely because they left open their options for obtaining food. Put another way, village life based entirely on agriculture would not have lasted very long.

Two rockshelters recently excavated on Pinto Canyon Ranch in west-central Presidio County (about 65 kilometers north of La Junta) hold evidence of foraging trips taken by prehistoric peoples from the river settlements. The data from Tres Metates and Potsherd rockshelters show that the intertwined lifeways recorded by the Spanish have considerable time depth in the region—minimally 300 years, and probably earlier, than Ydoiaga’s 1747 entrada.

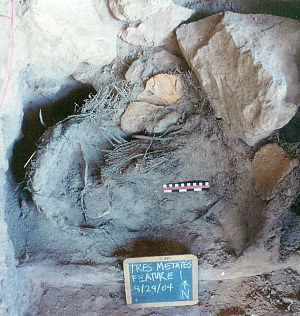

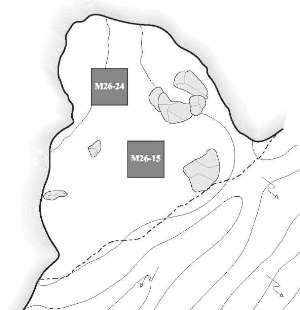

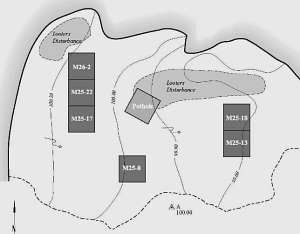

Tres Metates is a very large and spacious rockshelter, with a floor area of just over 100 square meters and a ceiling of over four meters in height. Six 1-x-1 meter units were excavated during testing—with three of these creating a 1-x-3 meter rectangle in the western portion of the shelter and another pair side-by-side in the eastern half.

Tres Metates was well stratified, although curiously, only Late Prehistoric archaeological remains were found. The sedimentary layer the perishable feature was resting upon was the absolute lowest layer containing the evidence of cultural activity at the site.

A pit feature (M26-2) containing several specimens of corn and beans was found in the northernmost unit in the western half of the shelter. These agricultural products were being stored in a prickly-pear and shrub-lined storage pit alongside such wild plant foods as prickly-pear, yucca, agave and various other flora. All of this was in association with a single sherd of El Paso Brownware, a common pottery type of the La Junta phase. Another sherd of Carretas Polychrome, a Casas Grandes ware from northwestern Chihuahua, was found nearby.

Potsherd Shelter is a much smaller site relative to Tres Metates. Only two 1-x-1 meter units excavated, one placed towards the rear while the other was placed just inside the shelter’s dripline. Potsherd shelter has been extensively used by undocumented immigrants and javelina in recent times, which has unfortunately disturbed the archaeological deposits at the site. All of the pottery sherds found at the shelter were found within these disturbed areas. Nevertheless, their provenience at the shelter itself is what is most telling. Though definitive associations with other artifacts found at Potsherd cannot be made, what can be said is that foraging groups carrying a pot or pots certainly occupied Potsherd during the Late Prehistoric period.

Potsherd Shelter yielded four sherds of Chupadero Black-on-White, a widely traded pottery type made in south-central New Mexico, and two sherds of untyped Casas Grandes redware. While relatively few in number, the sherds from these two sites, as well as others from additional Pinto Canyon Ranch sites, represent some of the most concentrated prehistoric ceramic remains found in the “interior” Big Bend, an area where pottery is exceedingly rare away from the rivers.

The use of non-local ceramics is characteristic of the La Junta phase. El Paso phase earthenwares from the Jornada Mogollon area are the dominate pottery types, but other Southwestern pottery types such as Chupadero occur as well as Medio phase wares from Casas Grandes. The reliance on these imported ceramics has lead to the idea that the La Junta phase groups were either Jornada Mogollon colonists or were indigenous peoples taking part in the Casas Grandes interaction sphere. Whatever the case, it seems clear that foragers carrying ceramic wares typical of the La Junta phase, and of the riverine-based settlements, were traveling to the area now known as Pinto Canyon Ranch with some regularity.

The storage feature at Tres Metates offers perhaps the most compelling evidence that extensive foraging was still a feature of prehistoric life in the area after the adoption of cultigens. This feature was constructed in a pit and later filled with banana yucca and prickly-pear fruit (only the seeds survive), as well as mesquite beans and chenopod seeds along with other edible native plants. All of the plants and plant parts found within the feature are known from ethnohistoric and ethnobotanical accounts to have been used for food across the American Southwest. But, even though numerous edible plants had been gathered during the occupation of the rockshelter, cultigens (the corn and beans) were also in use. This is a classic example of what Ydoiaga learned during his trip to La Junta—crops were available, but this did not diminish the need to continue gathering wild plants. One of the prickly pear pads comprising part of the feature lining was sent for radiocarbon dating. The pad dated to ca. A.D. 1400 during the latter part of the La Junta phase.

This date also falls within the Cielo Complex, the archeological designation for the contemporary hunting and gathering society that co-existed with La Junta. Ceramics are never found at Cielo Complex sites, even base camps located with a few miles of La Junta phase villages. Clearly the two groups interacted, and they both used similar kinds of stone tools, but they seem to have maintained distinctive identities as signified by different kinds of dwellings, different settlement patterns, and differential use of pottery.

In sum, there is convincing evidence on Pinto Canyon Ranch of foraging trips taken by La Juntan groups into the hinterlands surrounding the river settlements. Plant foods were certainly being sought, although game was probably being hunted as well. It is unknown why ceramic vessels were necessary during trips into what can be very (very!) rugged country, but, for whatever reason, they were. And the remains of the vessels firmly link these occupations within the La Junta phase.

A seasonal foraging lifestyle would have diminished the risk involved with reliance on the unpredictable returns from small-scale agriculture in a marginal environment. And conversely, the use of cultigens provided insurance against a wildly fluctuating wild resource base dependent on unpredictable rainfall. It seems unlikely that we will ever be able to neatly sort out the ethnic identities of groups who used this dual strategy during the La Junta phase. But we can appreciate the beautifully articulate way these Late Prehistoric peoples made their living in the unforgiving desert environment of the Big Bend. It was not either/or, it was both. Farming and foraging.

Contributed by John D. Seebach.

Sources:

Kelley, J. Charles

1952 Factors Involved in the Abandonment of Certain Peripheral Southwestern Settlements. American Anthropologist 54:356-387.

Madrid, Enrique R., translator

1992 Expedition to La Junta de Los Rios, 1747-1748: Captain Commander Jospeh de Ydoiaga’s Report to the Viceroy of New Spain. Office of the State Archeologist Special Report 33, Texas Historical Commission, Austin.

Miller, Myles R. and Nancy A. Kenmotsu

2004 Prehistory of the Jornada Mogollon and Eastern Trans-Pecos Regions of West Texas. In The Prehistory of Texas, edited by Timothy K. Perttula, pp. 205-265. Texas A&M University Anthropology Series No. 9, Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

Seebach, John D.

2007 Late Prehistory Along the Rimrock: Pinto Canyon Ranch. Papers of the Trans-Pecos Archaeological Program 3, Center for Big Bend Studies, Sul Ross State University, Alpine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This 2007 report by John Seebach details the archeological research at Tres Metates and Potsherd Shelter. |