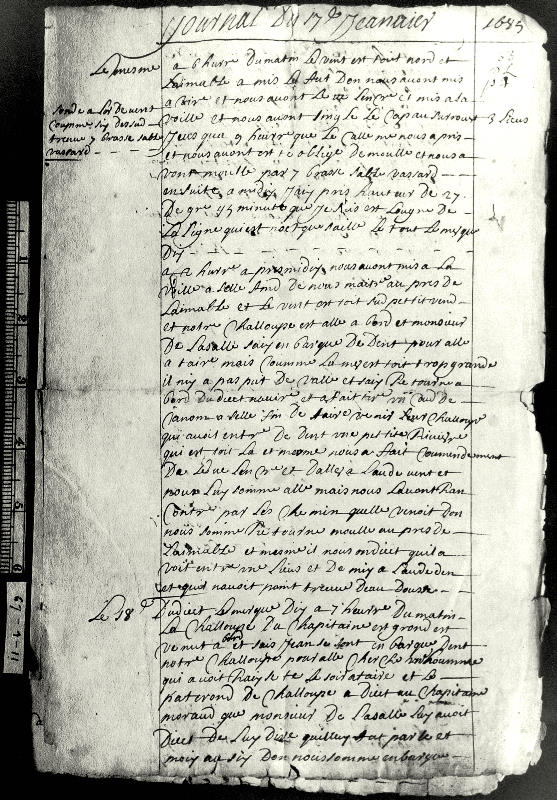

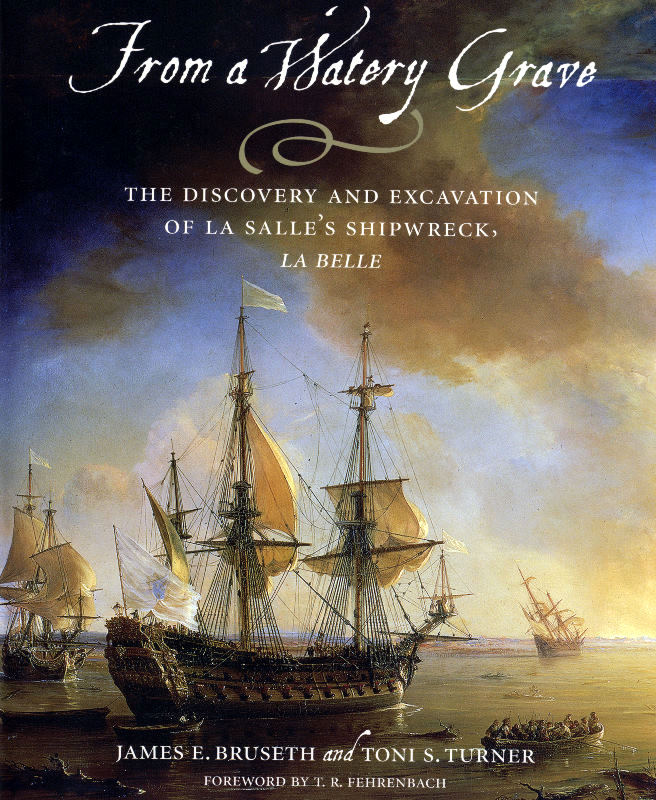

On a cold winter day in 1686, the small French ship Belle ran aground on the Texas coast, the victim of a run of bad luck and a howling north wind. The Belle was the last of four ships of the expedition led by Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle. La Salle had come to establish a colony near the mouth of the Mississippi River with multiple aims that included providing a warm-water port to serve the fur trade and a base for invading Mexico. France and Spain were then at war, and La Salle, with the backing of his king, intended to challenge Spain's domination of the Gulf of Mexico. This was not La Salle's first journey to the New World. In 1669 La Salle had set out to explore the Great Lakes region of North America. By 1682 he had reached the Illinois country, establishing trading posts along the way. From the mouth of the Illinois River, he began a journey of more than a thousand miles, following the Mississippi River to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. There he laid claim, in the name of Louis XIV, king of France, to roughly one-third of the territory of today’s continental United States. In light of such monumental successes and the hope of conquering more territory—including the Spanish silver mines in northern Mexico—the king was persuaded to back La Salle’s grandiose plan, providing ships, supplies, and personnel to carry out his vision. The king’s largesse, however, had limits. Whereas La Salle saw a need for four ships, the monarch agreed to provide only two: the small frigate Belle and the escorting warship Joly. To augment his force La Salle—drawing ever more heavily on borrowed money—leased from private merchants two additional vessels, L’Aimable and the ketch Saint François, and purchased additional trade goods and supplies. Sailing into HistoryThe small fleet embarked from the French port of La Rochelle with high hopes of establishing a French colony on the Gulf and fulfilling La Salle's dream. Misfortunes began before the expedition reached the Antilles. On the coast of Haiti the Saint François was seized by pirates. Further along on the journey, grievous errors in maps and knowledge of geography led La Salle to believe the mouth of the Mississippi lay much farther west than it actually was. In January 1685 the remaining three ships made landfall on the Texas coast, some 400 miles from the Mississippi. The landing site was in the territory of the Karankawa, whose enmity the French soon aroused. It was uncharted territory, with no European settlement nearer than hostile Mexico or the post La Salle had established in Illinois. Episodes of misfortune—made worse by inept leadership—rose in succession. A major setback was the wrecking of the Aimable, the store-ship carrying most of the would-be colony’s supplies, which ran aground while trying to enter Matagorda Bay. A large portion of the supplies and provisions was lost as the ship broke up and sank. The warship Joly, due to return to France once La Salle reached his intended destination, carried L’Aimable’s crew and a few persons who recognized the futility of the colony and refused to stay. Left behind was an array of fearful and homesick colonists who had no idea where they were. While La Salle sought the Mississippi, a temporary settlement was set up on the bank of Garcitas Creek some five miles above its mouth in Lavaca Bay. The small complex of crude structures afforded scant protection from the unruly Karankawans, however, who waited in ambush for those who left the settlement singly or in small groups. Hardly worthy of being termed a fort, the settlement has been called Fort St. Louis only because of historical error. With the settlement complete, La Salle loaded the Belle in readiness for making a sea search for the Mississippi. He placed on board items that would be needed if he should find his river and fulfill his plan to move the settlement there. He then embarked on a mysterious journey westward, leaving the Belle in an insecure anchorage in the charge of the ship's mate, Tessier, who was often in a drunken state. In La Salle’s absence, misfortune plagued the Belle. Already the ship’s complement of 27 men had been reduced by the death of the captain and five members of his crew who were caught away from the ship and murdered by the vengeful Karankawa. Six others, including the most experienced sailors who gone ashore in the ship’s lifeboat for water, either drowned in the bay while returning to the ship at night or were slain by Indians. Loss of the lifeboat proved crucial. Without water, the remaining crew suffered severe hydration—all except Tessier, who took charge of the store of sacramental wine. At last anchor was weighed to seek a more favorable location, but too late. A fierce northerly wind arose, and the unskilled and enfeebled crew was unable to work the rigging. In desperation, they dropped the bow anchor, but it failed to hold. As the ship was driven southward across the bay, the anchor dragged until the ship plunged stern first into the reef of barrier sand known today as Matagorda Peninsula. Still some distance from shore, the crew was unable to free the ship. Lacking the lifeboat, two men attempted to reach the shore with a poorly constructed raft. The raft came apart; one man swam ashore, but the other drowned. At last a more solid raft was built, and the crew was able to set up camp on the beach and ferry supplies from the wreck until the ship began to settle into the bottom and the cargo became submerged. For three months the Belle’s castaways remained isolated on the peninsular strip of sand, lacking the leadership of a resolute captain and a boat for crossing the bay. For sustenance, they supplemented provisions saved from the ship by fishing, gathering oysters, and shooting ducks. At last, however, they began to feel the pinch of hunger and set out to look for the means of escape. By good fortune, a canoe that had escaped the French on the far side of Pass Cavallo turned up at the water’s edge. Thus, the castaways were finally able to cross the bay to reach the settlement. Of all those whom La Salle had left on board the Belle—including the original crew of 27 and several men he had placed there in irons—only half a dozen survived: the mate Tessier, the Abbé Chefdeville, the useless Marquis de Sablonnière, a soldier, a young lad, and a servant girl from Saint-Jean-d’-Angély Meanwhile, La Salle himself, with a few followers, had marched eastward, hoping to reach the post on the Illinois River. When nearing the country of the “Cenis,” or Hasinai, in eastern Texas, he was brutally murdered by his own men. Almost two years later, a Karankawa band, feigning friendship, fell upon the twenty-odd persons remaining at the settlement on Garcitas Creek. Only half a dozen children were spared, to be ransomed later by Spaniards and taken to Mexico City. More than a year after the Belle’s loss, she was discovered by a Spanish expedition that had come looking for La Salle. The discovery was recorded in the diary of the pilot, Juan Enríquez Barroto, who recognized the little frigate as a warship from its six pieces of artillery and five swivel guns. The starboard side, the deck, and the prow were under water. The Spanish pilot’s description of the location would point the way for archeologists three centuries later. An Unprecedented ExcavationThe Belle remained mired in mud for 310 years, untouched but not forgotten. After years of unsuccessful searching, archeologists from the Texas Historical Commission (THC) finally found the prize in 1995. The crew discovered one of the Belle's cannons, an elaborately inscribed gun that confirmed the age and identity of the wreck. Properly excavating the shipwreck would require one of the most extraordinary engineering feats ever associated with an archeological excavation in Texas or anywhere else in the world. In 1996, at a cost of over $2 million, a double-walled cofferdam was built around the sunken ship. This allowed THC archeologists to pump out the wreck site and excavate the Belle almost as if they were on dry land. The nine-month excavation yielded equally astonishing results: gooey gray mud had encased the Belle and sealed its contents from the air. Most of the ship's stores—wooden boxes jammed with trade goods, tools to support a variety of trades, muskets and munitions, yards of rope, cannons, dishes, and more—were found in remarkably good condition. Here, for the first time, was an intact 17th-century French colonizing kit containing everything needed to establish a colony in the New World. Even the ship's hull and timbers were intact—though water-logged and fragile—still looking very much like they did when La Salle last saw them. The timbers still bore the original numbers carved into each piece to aid the ship's builders in assembling the Belle. For archeologists and others interested in Texas history, the quantities of astonishingly well-preserved artifacts and the ship itself represent a far more valuable and informative treasure than gold bars and silver coins. (Those, too, have been recovered from a shipwreck on the Texas coast, but that is another story.) The THC's unprecedented excavation was completed in 1997 under the direction of Dr. James Bruseth, director of the Archaeological Division. But the discoveries from La Belle did not end in Matagorda Bay. The thousands of recovered artifacts, dozens of wooden chests and barrels, and the complete set of ship’s timbers were brought to the Texas A&M Conservation Research Laboratory, where a painstaking process of cleaning, documentation, and preservation was undertaken under the direction of Dr. Donny Hamilton. Over a period of nine years, enormous concretions of artifacts and other remains were picked apart, conserved, analyzed, and identified, an undertaking tantamount to a second “excavation” of the shipwreck. Analysts from across the country also have joined in the process and have provided comparative information from other 17th-century French sites. To date, more than one million artifacts from the Belle have been conserved and catalogued, and many of these objects are now on display in Texas museums. The ship's hull has been reassembled in a giant vat filled with water and a stabilizing compound that is gradually replacing the water and hardening the wet wood. The reconstructed Belle ultimately will be on display for public viewing in the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin. Regional museums along the coast have joined in partnership to help present this slice of early Texas history to the public. The La Salle Odyssey Trail guides visitors to six museums with pertinent exhibits on La Salle, La Belle, and the short-lived French settlement, Fort St. Louis. The story of La Belle did not end with its excavation and analysis. Three hundred years after its sailing, the French government made claim to the shipwreck and all its contents, based on the International Law of the Sea, a doctrine which gives ownership of official naval vessels to the "flag nation," the country whose flag the ship flies. In 2003, however, following negotiations between the THC, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, and representatives of the French government, a treaty was signed conceding ownership to France but giving day-to-day care of La Belle to the Texas Historical Commission. In This ExhibitThis exhibit is a collaborative effort among researchers in several institutions to bring the story of La Belle to a world-wide audience via Texas Beyond History. In the sections following we focus chiefly on the remarkable archeological recovery of the shipwreck and the analysis and preservation of its contents. Discovery and Investigations details how the ship was found and how excavations by THC archeologists were conducted inside the cofferdam. Explore the Shipwreck provides an interactive opportunity to view the wreck and the cargo as it was seen by excavators. Excavations in the Laboratory highlights the painstaking recovery and conservation of artifacts at the TAMU Conservation Research Laboratory. Treasures of La Belle presents a gallery of artifacts from the shipwreck's amazing trove as well as an in-depth look at two particularly unusual features: the "Mystery Chest," an odd collection of tools and belongings that may have belonged to La Salle himself, and the human skeletal remains found on board the shipwreck. Museums and Resources charts a course to museums on the Odyssey trail and provides links to a variety of K-12 educational materials and curricula focused on La Belle, La Salle, and Fort St. Louis. Clues from the Bones, led by Dr. Dirt, the Armadillo Archeologist, is a fun and educational science interactive for students focused on what has been learned about the human remains found on La Belle. A correlated Teachers Lesson extends learning about the shipwreck and the skeleton found on board. Credits and Sources provides background on the various participants and includes a compendium of print and web resources for learning more about the shipwreck. For more information about La Salle and his colonists, see the TBH companion exhibit on Fort St. Louis. |

|