Arrow points, a hallmark of the Late

Prehistoric period (about A.D. 800 to 1600), were among

the chipped stone artifacts found within the middens.

These artifacts were made during the same period that

radiocarbon evidence suggests was the principal period

of midden use. Shown from left are: a triangular arrow

point blank and Scallorn arrow points from the early

part of the Late Prehistoric. Click to enlarge. |

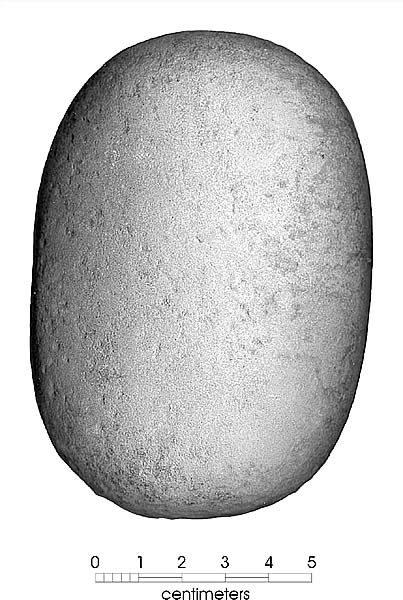

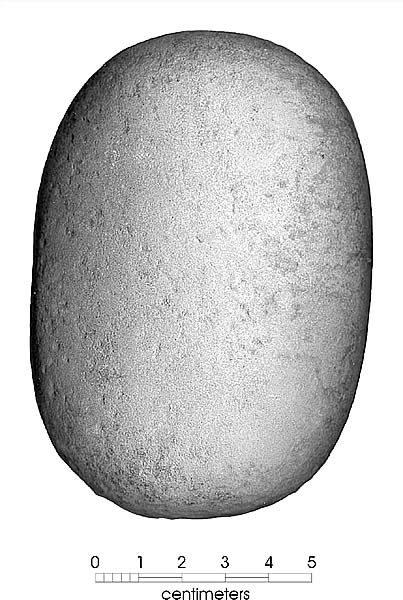

A stone mano from Camp Bowie. These

hand-held tools were used to grind seeds and nuts into

meal. Photo courtesy of CAR-UTSA. |

This chart shows the probability

distribution of calibrated radiocarbon dates derived

from 31 samples from Camp Bowie middens. The blue shading

marks the primary time period during which the middens

were used. Graphic by CAR-UTSA. Click to enlarge and

see complete chart. |

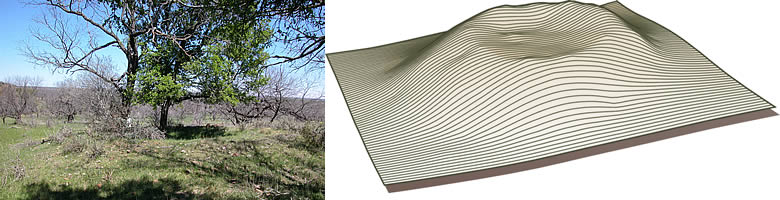

Burned rock midden density across

the state. The relative density by percentage of recorded

middens in counties is shown by color, grading from

peach tone (low) to red (high concentration). The areas

with no middens present are in counties that either

lack burned rock middens or have extremely low percentages

of middens. Black star marks location of Camp Bowie.

Graphic by CAR-UTSA. Click to enlarge. |

Paleobotanist and archeologist Dr.

Phil Dering, shown sampling the base of a lechuguilla

plant after baking it in an experimental hot rock oven.

Dering, who identified prehistoric plant remains from

the Camp Bowie middens, suggests that sotol and lechuguilla

are the most likely plant foods processed in middens

in the southern section of the Plateau, as well as to

the west. |

Acorns may have been an important

food resource on the Edwards Plateau. While some researchers

have suggested that burned rock middens represent acorn-processing

stations, the evidence for this interpretation is largely

circumstantial. No ethnographic accounts document the

intensive use of earth ovens for acorn processing.

|

This Ensor-style dart point was found

outside one of middens at Camp Bowie. This style was

made at end of the Late Archaic period just before the

intensive period of midden use in the area began. |

|

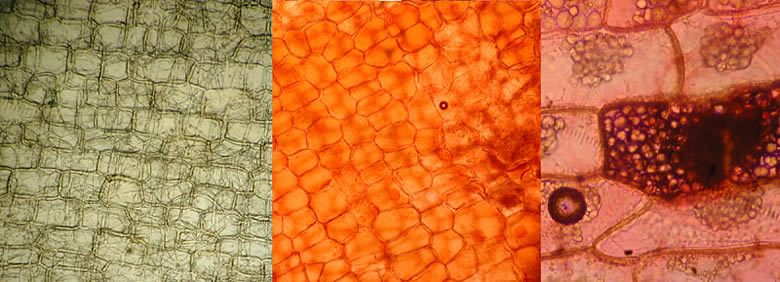

The majority of the identified bulbs were of

eastern camas (Camassia scilloides, also called wild

hyacinth). Central Texas is at the southwesternmost extent

of the historic distribution of eastern camas. Eastern camas

tends to grow in moderately wet areas. Its range may have

extended farther south and west during wetter periods in the

past. The bulbs have the highest nutritional value in the

spring, about the time the flower stalks begin to rise, and

this is likely when they would have been collected. It is

also the time of year when other plant resources are scarce

and most mammals are in poor condition (having burned up stored

fat to survive the winter).

The use of earth ovens to "bulk process"

camas is best known in the Pacific Northwest and northern

Rocky Mountains. Archeologist Alston V. Thoms (now at Texas

A&M) combined early historic accounts and archeological

evidence to show how the native use of western camas (Camassia

quamash) intensified over time. Initial use began

at least 7,000 years ago and the plant became a staple in

the region around 4,000 years ago even though it was a "high-cost"

resource (i.e., one that required lots of labor relative to

caloric return). Thoms linked the intensification of camas

exploitation in the Pacfic Northwest to increasing population

pressure. Texas researchers have applied many of Thoms' ideas

to understanding the burned rock middens of central Texas.

The plant food remains recovered from Camp Bowie

middens are of significance to researchers in Texas and beyond.

According to Dering, the collection is the largest preserved

assemblage of plant food from earth ovens recovered from sites

on the periphery of the Southern Plains. Further, the identification

of the dog's-tooth violet marks the first identification of

this plant from an archeological site. The best record of

its use by historic tribes comes from observations of the

Thompson River Indians in southwestern British Columbia. The

Thompson Indians understood that the raw bulbs of dog's-tooth

violet were poisonous, and they pit-baked the bulbs in order

to remove the poison.

Chipped Stone Tools and Bones

Archeologists found a variety of chipped stone

tools and animal bones at the Camp Bowie sites. In all, however,

only 16 diagnostic artifacts—those representing

distinctive styles known to date to certain time periods—were

found within the middens. These include, from oldest to youngest,

a Middle Archaic dart point, seven Late Archaic dart points,

and eight Late Prehistoric arrow points. With the one Middle

Archaic exception, these diagnostics fall into the same time

periods as the radiocarbon evidence discussed below).

A variety of different types of chipped stone

tools used for butchering animals, scraping hides, chopping

wood, and other daily tasks also were found, along with quantities

of chipping debris left behind by prehistoric tool makers.

Of interest were ground stone artifacts and

features related to food processing—the grinding or pounding

of plants, seeds, and nuts. Hand-held manos, or grinding

stones, such as the one shown at left, would have been used

in combination with grinding slabs, broad stones with shallow

depressions that served as receptacles for nuts and seeds

as they were pulverized or ground into meal.

Near one of the midden sites, archeologists

discovered 12 bedrock mortar holes. These deep, circular holes

in flat limestone bedrock have been worn from the pressure

of prehistoric people pounding food with stone or wooden pestles.

The mortars were grouped in clusters of three and nine and

were flanked by two middens. They are roughly 8 to10 cm (3

to 4 inches) in diameter and 6 to 10 cm (2.5 to 4 inches)

deep, although several were as large as 20 to 25 cm (8 to

10 inches) in diameter with depths up to 20 cm. A map showing

distribution of the mortars and middens can be seen by clicking

on the mortar image.

Archeologists also recovered animal bones in

the middens, though they were not common. Bone tends to weather

and deteriorate over time, whether on the surface or buried

in the ground. Among the identifiable bones were those of

white-tailed deer, bison, jackrabbits, cottontail rabbits,

birds, and turtles.

Dating the Middens at Camp Bowie

In addition to determining what the burned rock

middens at Camp Bowie were used for, the archeologists also

wanted to know when the middens were used. The most

reliable dating evidence at most prehistoric sites is radiocarbon

dating. Radiocarbon dates or assays

are statistical estimates of the age of the dated material.

Dates were obtained on 31 samples of charcoal from the middens—most

of the dated charcoal represents fragments of firewood. The

results indicate that most of the Camp Bowie middens were

used primarily during a relatively brief period spanning some

650 years.

The radiocarbon date chart on the left shows

that 28 of the dates fall during the Late Prehistoric period

between A.D. 750 and 1400. A single date falls slightly earlier

at A.D. 600 and two dates fall even earlier, within the Late

Archaic period, at 600 B.C. and 1200 B.C .

The charcoal samples chosen for radiocarbon

dating came from different levels within excavation units

in 17 of the middens. The sampling strategy was to try to

get multiple dates from different levels within the same 1-x-1-m

excavation unit. Whenever possible, the samples were obtained

from units positioned on the midden ring rather than within

the center of the midden. The thought was, if the middens

form from repeated raking out of a central feature, with the

removed material being deposited in the ring, then deposits

located in the ring would likely be less disturbed than those

in the central midden. It was assumed that the central areas

of the Camp Bowie middens had been repeatedly churned up as

earth ovens were built and rebuilt there.

Multiple samples were not available from some

middens and in these cases the archeologists attempted to

obtain samples from the lowest possible level within the midden.

The radiocarbon date chart presents the probability distribution

for each of these 31 (calibrated) midden dates from Camp Bowie.

The dates are grouped by site, and within each site, by increasing

depth. Dates from the same unit within a site are identified

by different color groupings. The samples from sites with

only a single date, or dates from different units within the

same midden, are shaded in black.

There are 10 sites that have multiple dates

from the same unit. These 10 color groupings in the chart

are represented by 23 different dates. In all cases with multiple

dates from different levels the radiocarbon dates form a pattern

as expected, with older dates occurring at increasing depth.

That is, in no case is there a statistically significant reversal

of the dates (such as older above younger). This striking

consistency is somewhat surprising in view of the fact that

many of the charcoal pieces were quite small and could have

moved up or down through the midden by gravity and disturbances

such as tree roots and animal burrows. Given these results,

it would appear that the midden rings gradually accumulated

and were seldom disturbed.

The Distribution of Burned Rock Middens Across Texas

CAR researchers used their understanding of

middens developed from the Camp Bowie data to look at broader

patterns in midden use. Their first task was to look at the

distribution of burned rock middens across Texas. They reviewed

over 9,000 site forms and compiled all site records of burned

rock middens for over 900 sites from more than 50 counties.

These data were combined with an earlier study by archeologist

Darrell Creel (TARL) to produce a data base of over 1,400

burned rock midden sites from 70 counties across the state.

When the density of burned rock midden sites is plotted by

county, the greatest concentration of sites is on the Edwards

Plateau and in southwest Texas.

Because using pit ovens required a great deal

of wood, it also is useful to compare the distribution of

burned rock middens to the distribution of woody vegetation,

especially oak, which is usually the dominate fuel wood found

in burned rock middens (also, charred acorns are sometimes

found in middens). However, because maps only exist for modern

vegetation patterns, the distribution findings are only a

broad indicator of differences in wood types.

The map on the left indicates that the distribution

of burned rock middens within the state is tightly confined,

concentrated primarily on the Edwards Plateau and in west

Texas. Comparisons of midden distribution with plant distribution

patterns (map on right) shows that, while the distributions

of oak and middens partially overlap, there are high densities

of middens found well southwest of the Edwards Plateau, in

areas where oaks are uncommon. It could be argued that a slightly

expanded prehistoric distribution of oak-dominated settings,

to the southwest and to the west, could accommodate as much

as half of the overall distribution of burned rock middens.

Nevertheless, even if we equate oak presence

with acorn processing, it is unlikely that oak accounts for

the entire distribution of burned rock middens. The distribution

to the west and southwest of the Edwards Plateau is clearly

not associated with oak, and by extension, clearly not associated

with acorn processing. Archeologists such as Glenn Goode and

Phil Dering have suggested that sotol and lechuguilla are

the most likely candidates for processing in burned rock middens

in the southern section of the Plateau, as well as to the

west, where sotol and lechuguilla are more common. A number

of ethnographic accounts document the use of these plants,

processed in earth ovens, throughout New Mexico, Northern

Mexico, Arizona, and into California. In addition, charred

agave has been recovered from earth ovens and middens in southwest

and far west Texas.

While the northern and eastern distribution

of burned rock middens coincides with oak-dominated vegetation

and could be correlated with areas of prehistoric acorn processing,

the area also lies within the southwestern end of the distribution

of geophytes (second map on right). Unlike oak wood, geophytes

could not have been used as a fuel resource and clearly were

being used for food, as indicated by their presence in the

Camp Bowie middens. While the idea that acorns were being

processed at burned rock midden sites cannot be entirely ruled

out, the fact that oak is the major wood identified in Central

Texas burned rock middens suggests that the occasional charred

acorns found in middens may simply represent incidental burning

associated with the use of oak fuel wood.

If geophytes—bulbs—rather than acorns,

were the focus of most middens in north-central Texas, why

are there no middens to the north? Eastern camas distribution,

for example, continues to the north, and other geophytes are

certainly in this northern section of the state also. The

distribution of oak continues to the north as well. We have

food and fuel, why don't we have middens? At present, archeologists

have yet to seriously address that question. We can suggest,

however, that if we are correct about geophytes, then the

answer probably lies in considering alternative resources.

Geophytes are "low return" resources,

they require a lot of work for the amount of nutrition they

provide, and potentially were used only for a limited time

during the early spring. We suspect that to the north other

plant resources may have been available that reduced the importance

of geophytes. At present, however, we have no suggestions

as to what these alternative resources might have been. The

absence of burned rock middens in many areas can be explained

by the lack of suitable rock. Earth ovens can be built without

rocks, but they may be harder for archeologists to recognize.

The southwestern distribution of burned rock

middens probably reflects the use of lechuguilla and sotol,

since it is unlikely that high densities of geophytes ever

were present in this relatively dry region. Counties with

the highest percentages of burned rock middens seem to be

on the border between the areas to the west, probably associated

with sotol and agave processing, and the areas to the north.

While these higher percentages might reflect both processing

of sotol and acorns, we would suggest that sotol, lechuguilla,

and geophytes are a more likely mix.

Summing It Up

Between A.D. 750 to 1400, Late Prehistoric peoples

repeatedly came to the Camp Bowie area to process large quantities

of bulbs in earth ovens heated by hot rocks. As favored oven

pits were reused over successive visits, burned rock middens

formed at many places on the landscape.

The radiocarbon evidence suggests several periods

of intensive use, separated by periods of lower use frequency.

These patterns may be related to fluctuations in the availability

of what was being processed in the middens, fluctuations in

availability of wood resources, more general changes in settlement

and subsistence, or a combination of these and other factors.

We believe that patterns in fuel wood resources

are a critical component in understanding patterns of midden

reuse. Because wood collecting was so labor intensive and

because wood resources would have been locally depleted over

time, the pit ovens may have been abandoned periodically until

the area's trees had time to rejuvenate.

In addition, the differential distribution of

these fuel wood resources may help to account for the strong

association of burned rock middens with oak, an association

that has previously been seen as related to the use of acorns.

Considering the spatial distribution of burned

rock midden sites across the state, it is likely that two

different sets of plant food resources (sotol and geophytes),

each with different spatial distributions, might be the major

food resources processed in middens within the state.

There is a strong likelihood that the Camp Bowie

middens were ovens where geophytes were processed. Over hundreds

of years, prehistoric people traveled to the area to harvest

and process bulbs, particularly camas— the principal

resource—during a short seasonal window of time, in the

early spring. The evidence of their culinary handiwork still

remains in the numerous burned rock middens and in an array

of other data.

Managing Camp Bowie's Cultural Resources

Fourteen of the Camp Bowie burned rock midden

sites were determined eligible for the National Register of

Historic Places. For National Guard training purposes, these

sites are considered "sensitive environmental areas"

and are officially "off limits." These areas are

monitored regularly by TXARNG training site managers and TXARNG

cultural resource staff to ensure that they remain undisturbed.

In the event that training activities or military construction

threatens to impact any of these sites, the state historic

preservation office (Texas Historical Commission) as well

as the Native American tribes that historically lived on what

is now Camp Bowie would be consulted and a reasonable compromise

would be sought among the various interests.

Through the cultural resource management process,

the Texas Army National Guard is able to continue its training

programs at Camp Bowie to help ensure national security, while

minimizing the loss of important historic information. This

balanced consideration is precisely the outcome envisioned

by Congress when the National Historic Preservation Act was

passed in 1966.

|

White dog's-tooth violet in bloom,

a similar variety to the type recovered from a Camp

Bowie midden. The finding of the prehistoric specimen

of this bulb in an archeological context was a first

in North America. Photo by Thomas G. Barnes, USDA-NRCS

PLANTS Database. Click to enlarge. |

Late Archaic dart points were the

other midden artifact types useful in dating the middens.

Two radiocarbon samples also fell within the Late Archaic

period, at 600 B.C. and 1200 B.C. The dart on left has

the tell-tale "pot-lid" fractures and pinkish

coloration derived from burning; it may have been inadvertently

included within the earth used to cap the ovens. |

This bedrock mortar, one of 12 discovered

in a cluster at Camp Bowie near two burned rock middens,

likely was used with a pestle for pounding foods such

as seeds or nuts. Photo courtesy of TXARNG. Click to

see distribution map of middens and mortar holes. |

| FAQ: What are

the Archaic and Late Prehistoric periods?

The Archaic period or era is a

very long span of human history in North America that

began about 9,500 years ago (7,500 B.C.) and lasted,

in the Camp Bowie area, until about 1200 years ago (A.D.

800). The Archaic concept was originally conceived ...

>>read

more<< |

Wood vegetation across central and

west Texas. The area in purple is predominately oak;

the green area is mesquite-juniper. This map, a simplified

compilation of various modern distribution maps, is

not an accurate reflection of prehistoric patterns which,

over time, were dramatically altered by both climate

change and radical changes in land-use practices during

the last 125 years. Nevertheless, the map provides some

indication of large-scale differences in distribution

of wood types . White star marks Camp Bowie location.

Click to view full map. |

Camas distribution across the United

States. Eastern camas still grows in central Texas,

but it was probably much more common during certain

times in prehistory when the climate was more moist.

Most of the bulbs found in Camp Bowie middens were of

this species. Black star marks Camp Bowie location. |

Common camas (Camassia quamash) in

flower. These grow primarily in the northwestern United

States and have been found in archeological sites there

as well. Photo by William and Wilma Follette. |

|

Fourteen of the Camp Bowie burned rock midden sites

were determined eligible for the National Register of

Historic Places. For National Guard training purposes,

these sites are considered "sensitive environmental

areas" and are officially "off limits."

Through the cultural resource management process, the

Texas Army National Guard is able to continue all of

its training programs at Camp Bowie to help ensure national

security, while minimizing the loss of important historic

information. |

|