By 1726 the mission was in operation at its

third location. The friars had been encouraged by reports of Indian groups that expressed enthusiasm for a Spanish mission.

The area selected was described as having good water, an abundance of timber, suitable land for

cultivation, and plenty of stone for construction. The new mission would serve the Aranama and Tamique

Indians and was to be located on the south bank of the Guadalupe River just west of Presidio La Bahia. This mission was in use until 1749 when it was moved a final time to a spot along the

San Antonio River in Goliad County.

Historical records documenting the third location of Espíritu Santo in the area today referred to as Mission Valley are scarce. Although a number

of documents mention the mission and its location, the majority of the records focus on military

matters at the related Presidio La Bahia on the other side of the Guadalupe River. No maps, for

example, of the layout of the mission have yet been found. Furthermore, little to no information is

written about the daily lives of the friars or the mission Indians.

The archeology of Espíritu Santo at Mission Valley,

therefore, is critical for understanding the arrangement of the mission structures and for

gaining insight into the everyday lives of the people that resided here. Furthermore, archeology can address many questions rarely addressed through historical records, as well as produce physical evidence of

the acculturation process and/or the persistence of native traditions.

Archeological investigations at the site were led by Thomas R. Hester, professor of anthropology and director of TARL at the University of Texas at Austin, and Tamra Walter, then a graduate student at UT-Austin. Two field schools of the Texas Archeological Society as well as a UT-Austin field school were conducted at the site, with work focused on several components of the mission complex. The

information recovered from these investigations yielded data concerning the mission structures, the

mission Indian "quarters", the sandstone quarry, a lime kiln, two diversion dams, and an acequia

system.

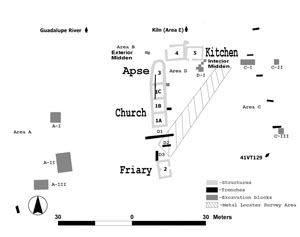

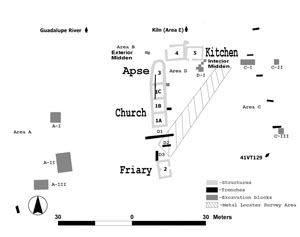

In all, the remains of five mission buildings were documented including the friar's quarters, the mission

church, an apse, and possible refectory or kitchen. All of these buildings were constructed from

sandstone taken from a quarry about 1 km (.6 miles) south of the mission ruins.

Large-scale excavations outside

the immediate area of the mission structures where many of the neophytes probably camped while staying

at the mission were conducted in order to recover information about these native residents. The

artifacts recovered from these investigations included bone-tempered pottery, large quantities of

animal bone and freshwater mussel shell, scrapers, Guerrero arrow points, drills, small bits of metal,

a few Spanish Colonial ceramic sherds (including majolicas and lead-glazed earthenwares), and several

glass trade beads.

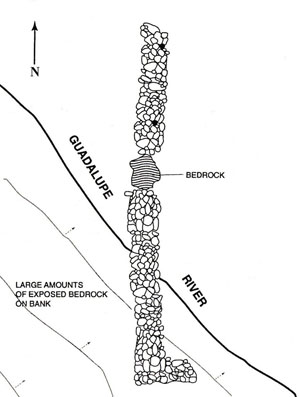

The discovery of an almost completely intact limekiln approximately 100 yards northeast of the

mission ruins provided a unique opportunity to examine another aspect of the mission complex. Locally

available caliche rock was collected and reduced in this kiln and probably others primarily in order

to make lime for the production of mortar. This simple, updraft subterranean bank kiln represents a

unique feature that is rarely found in such an excellent state of preservation at sites from the

Spanish Colonial period. Its construction and use reflects the importance of erecting permanent

structures of stone at the site. Lime was often considered more desirable for the long-lasting

success of stone buildings like those built at Espíritu Santo. The collection of caliche and the

operation of the kiln likely were jobs carried out by the mission Indians who provided the bulk of

the labor force.

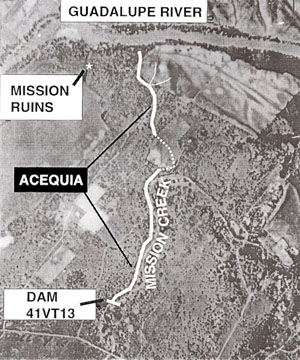

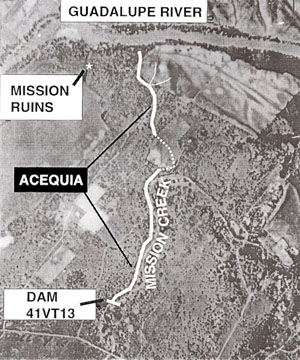

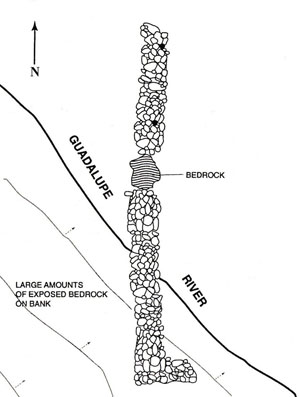

From historical records, we know that almost immediately after the move to Mission Valley was

completed, construction on a dam and acequia was underway. Despite considerable efforts and countless

hours invested in the building and maintenance of two dams (one built along Mission Creek and the

other along the Guadalupe River) and more than a mile of canals, attempts at irrigation were

unsuccessful. Periods of drought and flooding during the beginning years of the mission are believed

to be the major cause for the failure of the dams and acequia system.

After abandoning attempts to

irrigate their crops in 1736, the missionaries turned to dry farming which proved to be much more

successful. Again, the neophytes were most likely the individuals who were responsible for

constructing and maintaining the dams and acequia. As with most Spanish missions, the missionaries

trained the Indians in farming, herding, and other vocations as a part of the conversion or "civilizing" process. The mission Indians were expected to labor in the fields and herd cattle in a

concerted effort by the friars to make the mission self-sustaining and eventually profitable.

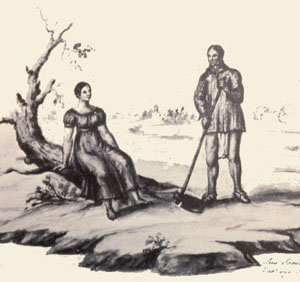

The Indians of the Mission

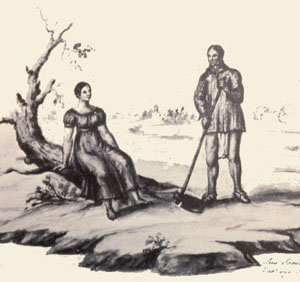

While historical records tell us that the Aranama and Tamique Indians were the main indigenous

groups to occupy the Mission Valley location of Espíritu Santo, they provide little else in regards

to their ways of life, religion, and social organization. There are a few historic and ethnohistoric

accounts that relate some information about the Aranama but even fewer provide details about the

Tamique who are believed to be a sub-group of the Aranama.

Most scholars agree that the Aranama were

a group of hunter-gatherers that lived near the Guadalupe River Valley. Both groups are thought to

have lived in small, nomadic bands and hunted deer and bison. During an inspection tour of the area

in the 1720's, Pedro de Rivera (1727) describes the native inhabitants at Espíritu Santo as pagans who

wore animal skins of bison and deer. A later account in 1854 provided by an early settler of Victoria

depicts the Aranama as "a temperate class of aborigines that "did not indulge in the use of ardent

spirits" and who were fond of painting their faces and bodies.

When the mission was moved for the final time to the San Antonio River near present-day Goliad, the Aranama and Tamique

continued to make up the majority of the Indian groups residing there. While at the mission, the

neophytes were trained in both farming and ranching and a number of the mission Indians became quite

skilled as vaqueros. Typically men worked in the fields or tended cattle while women cared for

children at home or were taught to spin and weave cotton and wool.

The daily routine of the mission

included prayers, mass, work, and meals. This routine was enforced by the friars with help from Indian

overseers and a few presidio soldiers stationed at the mission to help in the instruction of the

neophytes. For many of the formerly nomadic Indians, this strict ordering of life proved too taxing

and as a result it was not uncommon for many of them to abandon the mission only to be brought back

by search parties made up of presidio soldiers.

While things did improve at Mission

Valley after the abandonment of the acequia system in 1736, the Aranama and Tamique did not appear to

be permanent residents as is reflected in the lack of stone Indian barracks. Although a few trusted

Indians may have lived year-round at the mission, the vast majority continued to camp outside the

compound walls, apparently incorporating the mission into their seasonal movements as food supplies at

Espíritu Santo permitted. This situation changes at the fourth location of the mission where a number

of stone buildings were constructed and served as mission Indian quarters.

Despite accounts that estimate the congregation of 400 Aranama and Tamique Indians at the time of

its founding, the third location of the mission probably never sustained that number for long. The

first years of operation at Mission Valley were plagued with troubles. The padres were undersupplied

and had to use their own monies to help support the missionary effort, food was scarce, and their

crops were failing. Promises to feed and protect the natives may have been enough initially to entice

these groups to live and work at Espíritu Santo but eventually the missionaries had to turn them away

when supplies ran short.

Interestingly, the archeological evidence indicates that the Spaniards may

have been relying more on the Indians for subsistence in those early years. The remains of a variety

of local wild fauna including deer, freshwater fish, rabbit, turtle, and opossum found within the

walls of the mission compound suggest that the friars may have supplemented their diet with foods

brought by the Aranama and Tamique. Furthermore, given the lack of durable goods available to the

mission, it is not surprising that bone-tempered pottery, produced by the mission Indians, constitutes

more than 90% of the entire ceramic assemblage.

Investigations in the mission Indian "quarters" have provided the most information regarding the

native occupants of Espíritu Santo thus far. Archeological evidence of native occupation consists

mainly of mission Indian material culture and a number of features located outside the confines of

the mission compound. The features include small hearths and piles of discarded mussel shell and

animal bone representing the remains of meals prepared by the mission Indians. Analysis of the

materials recovered from this area indicates that neophytes continued to hunt and gather local fauna

and make and use stone tools including scrapers, drills, blades, and beveled knives. Spanish goods

and domesticated animals are also present in the mission Indian assemblage although in much smaller

quantities.

In general, it appears that their diet did not change significantly at this early date

regardless of the access to new, domesticated animals introduced by the Spaniards. As the cattle

herds grew and the mission became more self-sufficient during the later years at Mission Valley,

however, domesticated foods may have become more important to the mission Indian diet.

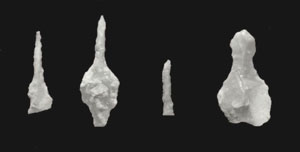

Likewise the use of stone tools does not appear to have changed greatly during this period and

the toolkit used by the natives is very similar to Late Prehistoric toolkits with the exception of

the Guerrero projectile point. The Guerrero point type makes its appearance in the archeological

record during the Spanish Colonial era in south Texas and Northeastern Mexico and is most commonly

found in mission Indian middens and Spanish Ranchos. Clearly, stone continued to be important for

the manufacture of tools although it should be noted that metal was generally scarce during the 18th

century in Texas thus accounting for some of the continued dependency on stone.

To date, the archeology at Espíritu Santo has yielded information regarding changes in native

diet and technologies. Both the Spanish and the Indians were impacted by the mission experience and

change was felt by all parties involved in its history. The missionaries relied on native products

such as ceramic wares and may have supplemented their diets with local game provided by the mission

Indians.

The Aranama and Tamique, on the other hand, continued to a certain degree to practice

traditional lifeways including the use and production of stone tools, the hunting and gathering of

local flora and fauna, and scheduled seasonal rounds dictated by the mission's available food

resources. The continued use of stone tools can be interpreted as an attempt to hold on to

conventional ways of life or a necessity or perhaps a bit of both. As seen in the faunal assemblage,

the mission diet reflects a certain reliance on native species during the early years of the

mission's operation when resources were scarce. As the mission herds grew however, beef may have

played a much larger role in the diet of the mission residents.

Obviously both the native and Spanish occupants of Espíritu Santo were experiencing rapid

changes as a result of cultural exchanges between the two groups. It is important to note, however,

that although it may appear that certain aspects of native culture persisted unchanged the

political and social contexts in which these traditional practices occurred was vastly different

from that of the pre-Hispanic era. European diseases profoundly effected native populations in the

New World including those of South Texas. Furthermore, groups such as the Apache were encroaching

upon the established hunting territories of the Aranama and Tamique as well other bands in the

area disrupting their way of life.

The continued use of certain items such as stone tools at

Espíritu Santo or the use of metal implements was unquestionably affected by availability,

necessity, and perhaps even social constraints. Mission life was without doubt structured and the

friars certainly had rules regarding what was appropriate behavior for the neophytes. The

acceptance or rejection of Spanish traits is perhaps better described as a negotiation process

between the Indians and the missionaries. The Aranama and Tamique were active participants in

this cultural exchange trying to adjust to the changing sociopolitical landscape and perhaps

preserve at least some elements of their traditional ways of life in the face of adversity.

Archeological investigations are on-going at the mission. Ideally new information will help us

address in more detail mission Indian life at Espíritu Santo and the strategies employed by the

Aranama and Tamique to maintain their ethnic identities.

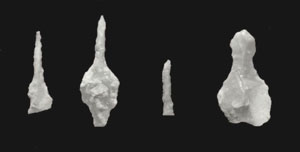

Guerrero arrow points are a standard at Texas missions. These triangular to lanceolate-shaped points are so-named for the missions in Guerrero, Mexico, the "type sites" for this late style.  |

|

|

Archeology gets underway at the site under a canopy of large oak and mesquite trees. According to historic records, the proximity to timber, stone, and water, w as a determining factor in selection of the third location for the mission. Photo by Thomas Hester.  |

Location of the mission structures. In all, five buildings were documented during investigations.  |

TAS crew members examine the apse of the mission church.  |

The friar's quarters.  |

This sandstone quarry supplied the stone used to build the mission.  |

Sites in the Mission Valley, including ruins of the mission, acequia, or irrigation channel, and a dam built along Mission Creek.  |

The Aranama Indians, as depicted in stylized fashion by an artist traveling with the Berlandier expedition. Painting by Lino Sánchez y Tapia, circa 1830s.  |

Excavations exposed the kiln in which lime was made. Lime is a key ingredient in making mortar used in construction of stone buildings and walls. Kilns are rarely found in such an intact state of preservation at Spanish Colonial sites.  |

After abandoning attempts to irrigate their crops, the missionaries turned to dry farming.  |

Bone tempered pottery, termed Goliad ware, was produced by the native inhabitants here as at most mission sites in south Texas.  |

Quantities of bone, mostly from cattle, were found in a concentrated deposit interpreted to be a refuse midden.  |

Stone drills.  |

Spanish Colonial ceramic sherds. These colorful, tin-enameled wares were mass produced in Mexico in a variety of styles, including Puebla Blue on White. Brought by wagon across frontier roads, the pottery was widely used in missions and presidios, but only as a supplement to the native-made, utilitarian Goliad ware.  |

|