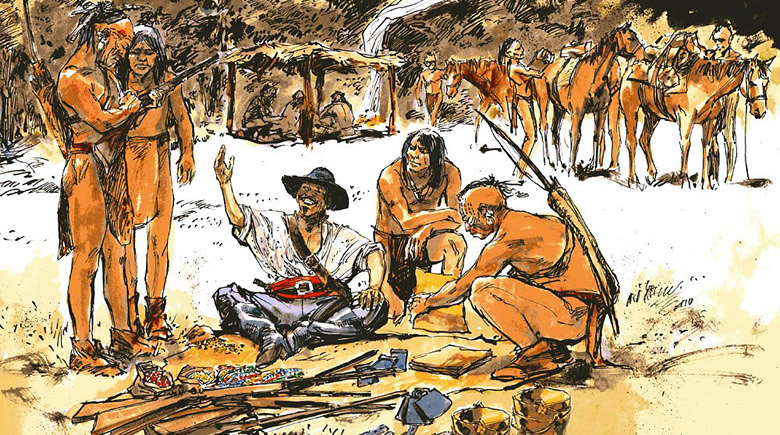

A trading session between a French trader and his Caddo partners and Kichai Indians at the Gilbert site, ca. A.D.1750, as envisioned by artist Charles Shaw. All of the items depicted are based on archeological finds.

|

||

| In the Post-Oak Savanna about 50 miles east of Dallas is an unusual archeological site, a place that played a little-known part in Texas history. Here, some 250 years ago, a Caddo-connected Native American group established a deer-hunting and hide-processing camp that produced thousands of deer hides for an international market. The hides were destined for Europe to create fine leather clothes for Parisians and other sophisticated folk, few of whom could have imagined the origin of their sleek and soft leather garments. Their tastes in fashion enriched the lives of an as-yet-unidentified group affiliated with the Caddo and Southern Wichita, possibly the little known Kichai. Whoever the Gilbert site occupants were, they possessed a wealth of European trade goods, particularly guns and other metal items, so many in fact that they abandoned perfectly good items including brand-new iron hoes. By the early eighteenth century, French traders operating out of Louisiana had created an extensive network of Native American partners and clients who provided deer and buffalo hides in exchange for guns and other European trade goods. While details of the French fur trade in the Great Lakes region far to the north are well known, the history of the French trade network in Texas and Louisiana is less known. For the Native American groups in Texas, French guns were particularly welcome because the Spanish, who then controlled most of the region (at least on paper), forbade their citizens to trade guns to native peoples. Beyond their value as weapons, guns were also prized because they could be traded readily for horses. In the early eighteenth century, Southern Plains groups such as the Comanche had large herds of horses, but relatively few guns, while the more settled groups in deep East Texas and further east in the Lower Mississippi valley had French guns, but few horses. Based on the archeological evidence at hand, the Gilbert site appears to have played a key role in the hide-gun-horse trade of the mid-eighteenth century, a French connection in the oak and hickory woods of northeast Texas.

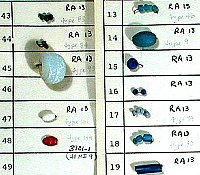

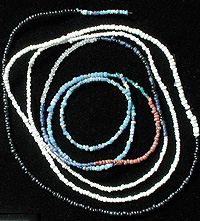

The Gilbert site is in northern Rains County near the upper reaches of Lake Fork Reservoir. To the west is the Blackland Prairie where buffalo country began. To the east are the Piney Woods, homeland of the Caddo. Given the extensive evidence of deer harvesting at the Gilbert site, its location in the Post-Oak Savanna was obviously no accident. Deer would have been much more common here in the mixed woods and grassland environment than either to the west, where it was more open, or to the east, with its dense forests. In fact, today the site is still part of a deer-hunting lease. The story of the archeological investigations at the Gilbert site is noteworthy in the history of Texas archeology. In 1962, volunteer and student archeologists from the Texas Archeological Society (TAS) and the Dallas Archeological Society (DAS) came together at the Gilbert site in northern Rains County and carried out landmark excavations under the direction of Dr. Edward Jelks and several other professional archeologists from the University of Texas. Almost 40 years later, the Gilbert site remains the only carefully investigated Indian site in Texas that has produced a large collection of French trade goods. As importantly, the highly successful, cooperative, and educational pairing of professional and volunteer archeologists established a tradition: the TAS Field School, an annual event ever since (see Birth of the TAS Field School). The partnership continued during the analysis and writing phases and, in 1967, the thirty-seventh volume of the Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society (BTAS) was entirely devoted to the Gilbert site, the combined work of 31 contributors. Volunteer archeologists continued to conduct research at the site until the early 1980s, often competing with collectors armed with metal detectors. A great deal of what we know about the Gilbert site today comes directly from the volunteer salvage efforts by R. "King" Harris, Inus Marie Harris, Jay Blaine, Jerrylee Blaine and other members of the DAS and TAS. It is because of the persistence and special interests of Jay Blaine, in particular, that much of the fascinating story of the Gilbert site is now known. Blaine says he owes as much to the Gilbert site as we do to him. During the initial 1962 work, Blaine was a newcomer to archeology—a "greenhorn," as he puts it. But he fell in with a good crowd especially his mentor, the late King Harris of Dallas, a legendary collector turned archeologist. Harris served as co-director of the 1962 investigations at the Gilbert site. One of the many things that set Harris apart from other volunteer archeologists is that he developed an extraordinary expertise in historic-era Indian sites and in trade beads in particular. The famous Bead Boards that Harris and wife, Inus Marie, put together contain examples of hundreds of varieties of glass trade beads, identified by country of origin and date. They still remain invaluable reference materials at research laboratories and museums across the country.

The Gun ManLike King Harris, Jay Blaine became an expert, in this case about metal artifacts—guns, swords, knives, kettles, hatchets, hoes and all manner of smaller metal things forgotten, especially gun parts. He first became interested in metal artifacts in the late 1940s when, as a college student in California, he was swept up into the state's fascination with the centennial anniversary of the famous '49ers. Blaine began reading historical accounts, including diaries, describing the terrible ordeals that befell the wagon trains that tried to cross the "40-Mile Desert" in western Nevada. This led to a visit to the area during a family vacation. What he found appalled and fascinated him—all sorts of scattered debris from pre-Civil War wagons. These things belonged in museums, he thought, and not knowing what else to do, he collected examples of some of the curious metal artifacts he found. Most he could not immediately identify, and so he began asking questions and reading obscure reference materials. Life intervened, and the Blaines moved to Texas where he became a postal supervisor. In 1960, Blaine stumbled across a copy of the BTAS and realized that there were others out there who were fascinated with the early history locked in scattered bits and pieces. So he joined the TAS and the DAS and began attending meetings and volunteering to help on digs. Through Harris he became involved with several historic Indian sites with curious metal artifacts. As part of the Gilbert analysis team, he was "sentenced to firearms—they would hardly let me look at anything else," he says, only half-joking. What he soon realized was that almost nothing was known then about French trade guns; even most of the reigning experts had a poor grasp of the intricacies involved in distinguishing similar parts made in different factories, different countries, and at different times. "I like to break into a system and see what it is composed of," Blaine says, and that is what he proceeded to do. Today, Blaine is acknowledged as one of the foremost authorities on metal artifacts. He has built a very important comparative collection of documented metal artifacts and, in the process, has become an expert in metal conservation and identification. Although he claims to be retired and "over the hill," his expertise is in demand. He continues to help archeologists and museums identify and preserve metal artifacts such as the traces of Coronado's 1541 expedition that have recently been found in the Texas Panhandle. Since it is largely through Blaine's detective work that much of the Gilbert site story can be told, we will turn to him for more of the tale (see French Connection in East Texas). |

||