The people were still moving from place to place over the seasons and over the years, but it seemed to some of the older members of the group that they were returning to the Naconichi Creek area with more regularity in recent years; to some of the people it began to feel like home when they came back to this valley. There were freshwater springs there, deep woods, and an abundance of game. All these things were important to the people because they had noticed the winters had turned colder and seemed to last longer, and shelter during these months was important. Their hastily-built structures were cold during the winter months.

Times were hard during the winter, and food was difficult to come by, except for what they had put aside or could carry with them, including a mass of hickory nuts that had been parched and a side of venison that had been dried and jerked. When it was all boiled together in their pots, along with some of their hickory nut oil stores, it made a good meal. If only the foodstuffs lasted longer and there was more variety at this time of the year (a good turtle stew would have been nice), but until then, everyone looked forward to the spring, and the greening of the woods, fruits, grasses, and seeds.

In the meantime, the people were also anticipating meeting up with their kith and kin, all living within a day’s walk of Naconichi Creek. This was a time to exchange news and information, meet with relatives and dear friends, perhaps find a husband or wife, or get one’s hands on a choice piece of stone or to successfully barter for a set of finished tools. This was a time of renewal, a time to give thanks for the good times, a time to remember the recently deceased, and a time to make plans for the future. The people were invigorated after every one of these larger meetings, and were sad to return homewards, knowing it would be a while before they would see their kin and friends again.

It was time to move again to the valley of the na-chawi (the Angelina River).

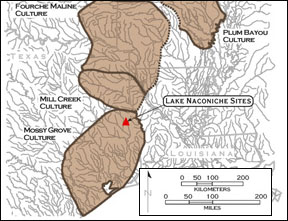

The Woodland period occupations at Lake Naconiche are components of the Mossy Grove culture, specifically, inland groups of that culture that lived in the Neches and Angelina river basins in East Texas over 2000 years ago. The Lake Naconiche Woodland sites were occupied during periods of continued cooler climate with periods of widespread vegetation change, and a very dry and cool episode ca. 2300-1800 years ago. Another shift took place about 1650 years ago, when peaks and valleys in temperature and precipitation occured, with warm periods culminating around 1000 years ago.

The Lake Naconiche Woodland sites are marked by low density scatters of lithic tools and debris, some sandy paste ceramic sherds, fire-cracked rock, and ground stone tools. Features such as midden deposits, indicators of prolonged activity, are rare at the Naconiche Creek and Boyette sites. The absence of this kind of evidence suggests only periodic use of the sites by mobile hunting-gathering foraging groups over more than 10 centuries.

The presence of ceramics hints at the beginnings of a more settled way of life, as the manufacture and use of ceramic vessels for cooking, storage, and food-serving implies that more extended stays may have occasionally taken place at the sites, perhaps after ca. A.D. 500/600. It is hard to disagree with the overall impression that Woodland period settlements were sporadic temporary encampments by small groups of people over a lengthy period of time.

Beginning some 2500 years ago, the Mossy Grove culture encompassed Woodland period archeological sites from the upper Texas Coast well into East Texas, including the upper part of the Attoyac Bayou basin where the Lake Naconiche sites lie. At least in some cases, the prehistoric peoples that we refer to as the inland groups of the Mossy Grove culture are considered likely to be ancestral to the prehistoric Caddo that lived in this part of East Texas after ca. A.D. 800, and as such are also ancestral to their descendants, the modern Caddo Nation of Oklahoma. Certainly not all Mossy Grove culture groups living in southeastern and eastern Texas are ancestral to the Caddo, particularly those living farther south. James A. Corbin suggested that inland Mossy Grove groups were contemporaries of the earliest Caddo to live in East Texas, and that gradually over time these groups adopted Caddo lifeways.

Everyday Activities

The everyday activities that took place at the sites during the Woodland occupations are best viewed as archeologically identifiable examples of the kinds of household activities that comprised the structure of everyday life: subsistence activities, such as plant collecting, hunting, cooking, and storage, as well as crafts such as pottery making, collecting and working lithic (stone) raw materials, and so on.

Because no individual Woodland period households have been identified at any of the Lake Naconiche sites, the activities seen in the archeological excavations at the two best known Woodland components (the Naconiche Creek and Boyette sites) represent a composite of activities undertaken by relatively mobile groups of likely varying composition, size, and intensity of occupation over more than 50 generations.

Cultivation and Wild Plant Collecting

The cultivation of squash gourds in East Texas began in the early part of the Woodland period. Squash was the first tropical cultigen grown and used by the ancestors to the modern Caddo peoples in this region. Squash rind fragments were recovered from archeological deposits at the J. Simms site (41NA290) daring after A.D. 400. No evidence was obtained that suggests maize, beans, or certain kinds of oily and starchy seeds were grown or consumed by groups that lived from time to time along Naconiche and Telesco creeks. Seed crops were probably not widely used as stored foods for winter use at this time, as the relatively mild temperatures in East Texas would have limited the length and severity of the winter season as well as the degree of reliance on stored foods.

The vagaries of preservation, the nature of the settlements, as well as the relatively few Woodland features, hinder a full appreciation of the wild plant collecting activities. The only wild plant foods documented are hickory nut and acorn, indicating an intensive use of hardwood mast as food stuffs. Nuts were probably parched and stored for later use, during the lean winter months, and also pounded to make a nutritious hickory nut oil to add to stews and other meals. Undoubtedly they also collected fruits, seeds, tubers, and roots as part of their diet, and were intimately aware of where and when these plant foods were available.

Other wild plants that were collected include the wood from oak, river birch, plum/cherry, elm, and pine trees. Sticks and branches from these trees were collected for use in fires for cooking and heating activities; some of these same pieces of wood may have been originally collected to construct temporary houses and other short-lived structures.

Hunting and Trapping

Hunting with stone-tipped dart points and trapping of game animals was an important subsistence pursuit for Woodland peoples, not just for meat, but also for pelts and hides, bones and other body parts as raw materials for tools and other accoutrements (e.g., deer brains for use in tanning). The most important game animal was the white-tailed deer. One bison-sized animal bone was found at Boyette, while a single bobcat was recovered at the Naconiche Creek site. Other animals that were hunted and trapped included beaver, turtle, rabbit, and squirrel.

Woodland period hunters were apparently aided in their hunting activities by their dogs. Domestic dog bones were recovered in archeological deposits at both Naconiche Creek and Boyette.

Storage

It is possible that one large 7th and 8th century A.D. basin-shaped pit feature (Feature 1/10) at the Boyette site was used for storage purposes, although its function is uncertain. It is also possible, based on the character of the fill, that it may have been used as an earth oven or cooking pit. A use for storage, as suspected, might suggest that sufficient food stores of some storable plant foods had been accumulated for use while the people over-wintered at the Boyette site.

Cooking

In Woodland times, the cooking of plant and animal foods probably employed several techniques. The archeological evidence points to the methods described, but certainly roasting over an open fire would have been a common practice that would be worth mentioning, even though it would not be detectable in the archeological record. The first would have made use of hot rocks for cooking in outdoor hearths, earth ovens, or smaller cooking pits, as the ability of stones to store and slowly release heat would have been ideal for use in ovens or baking pits. The second cooking technique probably employed by these Mossy Grove culture groups would have been boiling food stuffs in sandy paste pottery vessels. The adoption and use of sandy paste Goose Creek Plain pottery by hunter-gatherer foragers offered a better way to cook foods than the hot rock cooking/stone boiling in hide-lined pits or basketry of earlier times. Stews/broths could be cooked and simmered in ceramic vessels placed directly over the fire. The introduction of this new cooking technology after ca. 2500 years ago in Southeast Texas and in East Texas does not seem to be directly linked to the use of any domesticated crops or the simmering of starchy foods.

Pottery Making

The sandy paste and untempered Goose Creek Plain sherds are from compact and smoothed vessels made by coiling. The smoothing served to better weld the coils together before firing. Vessel forms are primarily jars with unrestricted (straight) rims, as well as simple bowls. Among the later 7th and 8th century sandy paste wares at the Boyette site are also carinated bowls and a bottle, common Caddo vessel forms.

The vessels have relatively thick walls, if unevenly so. The rims appear to have been made somewhat thicker than the vessel body walls to stand up to the cooking, stirring, and ladling of cooked food stuffs.

The Goose Creek Plain vessel sherds are from vessels fired in a wide variety of ways, suggesting that firing was not particularly well controlled by these early potters. Most pots were either incompletely oxidized during firing, or are from vessels fired in a reducing environment but then pulled from the fire to cool in the open air (thus becoming partially oxidized). Some sherds have a distinctive firing core, with an alternating dark exterior/light exterior cross-section, or lighter cores than their surfaces. These may represent vessels placed in a fire with the opening of the vessel facing into the fire. Alternatively, the lighter cores may be the result of a lengthy firing that burned off all organics, followed by the smothering to cause reduction and darkening of the exterior surface. Such firing methods were 2-3 times more common in Woodland contexts than in later Caddo ceramic assemblages.

There are a few tempered Woodland decorated sherds from the Naconiche Creek and Boyette sites that have clear affinities to ceramics being made and used by aboriginal groups in the Lower Mississippi Valley (LMV) between ca. 100 B.C. and A.D. 300. These are probably vessels that were made in the LMV and obtained by local Mossy Grove groups through trade or exchange. Present in the Lake Naconiche Woodland pottery assemblage are sherds from Marksville Incised, Marksville Stamped, and Indian Bay Stamped vessels.

While plain undecorated pottery dominate the assemblages, there are decorated sandy paste vessel sherds at both the Naconiche Creek and Boyette sites. Predating ca. A.D. 300, the only decoration on the sandy paste vessels was lip notching. Several vessels did have suspension holes on the rim. At the Boyette site in later Woodland contexts, the decorated sherds include primarily incised, punctated, incised-punctated, incised-rocker stamped, and rocker stamped sherds.

The incised sherds (with both narrow V-shaped and broad shallow lines) are principally from vessels decorated with a series of horizontal lines, although opposed, curvilinear, diagonal, and horizontal-diagonal elements are also present. Punctated sandy paste sherds have circular as well as tool punctated elements, arranged in straight or curvilinear rows. The incised-punctated sherds have circular/semi-circular, triangular, or paneled incised zones filled with tool punctations or large circular punctations. One body sherd—from a sandy paste carinated bowl—has straight incised lines with one row of circular punctations alternating with a row of tool punctations.

The rocker stamped body sherd has a single row of rocker stamps, part of a larger motif of curvilinear incised zones filled with rocker stamping. This rocker stamped pottery may be a sandy-paste example of an LMV pottery type known as Marksville Stamped, var.Troyville. The one incised-rocker stamped sherd, which is probably of the same pottery type, has a broad and shallow incised line that is likely part of a curvilinear zone filled with rocker stamping.

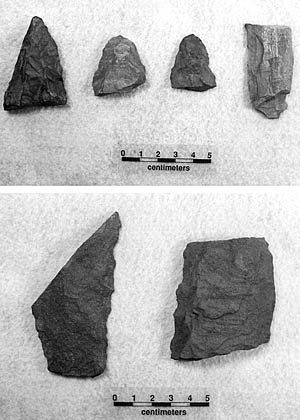

Procurement and Working of Lithic Raw Materials

Woodland groups relied on local gravels for the manufacture of chipped stone tools, but also made use of raw materials from stream and bedrock outcroppings of sandstone, hematite, and ferruginous sandstone to make groundstone tools. Local gravels included a variety of different colors of cherts, along with petrified wood— challenging to knap under the best of circumstances— and quartzites. The relatively high frequencies of local chert tools and debris at the Boyette site, on Telesco Creek, compared to sites on Naconiche Creek, suggests that there were local differences in the composition of stream gravels.

Non-local lithic raw materials were obtained—primarily in the form of finished or nearly completed tools—from sources along the Red River in Northeast Texas, farther afield in the Ouachita Mountains of southeastern Oklahoma, as well as Central Texas, for chipped stone tools. These materials were never common during the Woodland period, accounting for less than 4% of the dart points and between 4.5-10% of the lithic debris.

Woodland knappers had a core-based knapping technology. The strategy was to manufacture tools through the reduction of cores, or by the production of very large flakes. The generally small size of the local gravels greatly limited the availability of large flakes. So the knappers usually made the chipped stone tools through core reduction. In the bifacial reduction of cores and pebble masses, and the removal of the cortical covering, the cores and resultant bifaces were frequently broken through knapping failures. Discarded and broken bifaces of varying size, thickness, and shape are found in considerable numbers on Woodland sites in the local area.

Before about A.D. 700 the primary tools were Gary and Kent dart points, which were used for butchering/cutting and scraping tasks as well as weapons. Many of the dart points have been resharpened and re-used in non-projectile activities, as were heavy-duty cutting bifacial tools and gouges made from petrified wood and ferruginous sandstone. Other important chipped stone tools were expedient (informal) flake tools as well as drills, perforators, side scrapers, and end-side scrapers. The ratio of expedient to formal flake tools suggests some considerable expenditure of time in the more intensive processing and preparation of hides.

Early arrow point forms, perhaps adopted by ca. A.D. 700 in the region and used in Formative Caddo times as well, include Friley and Steiner forms. These have distinctive serrated blades and upturned barbs.

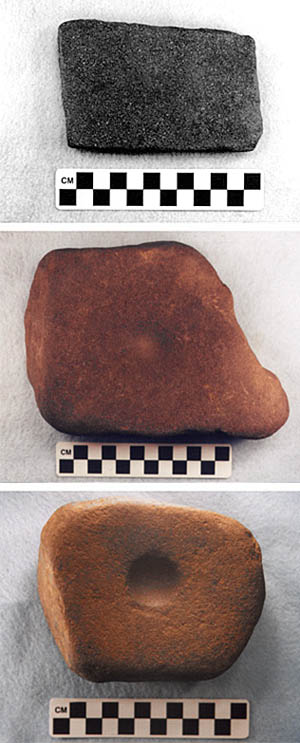

Grinding Plant Foods

Pitted stones and mano-pitted stones were the most important of the ground stone tools, along with manos and an occasional metate, mortar, and grinding slab. These tools were used in the grinding, pounding, and cracking of plant foods and nutshells in Woodland times.

Tree Felling and Woodworking

Unifacial gouges made from petrified wood were employed in woodworking activities, and an occasional chopper/shredder and hematite axe suggests a similar use for these tools, perhaps in clearing brush and small trees.

Craft Activities

Baskets, mats, and nets would have been made and used by the Woodland groups that lived in the Lake Naconiche area. However, no direct evidence of these craft activities was found during our work, due to very poor preservation conditions for such perishable artifacts.

Personal Ornamentation

No archeological evidence was recovered documenting any personal ornamentation by Woodland groups living along Naconiche Creek, or at least no ornaments such as beads were found. Traces of red ochre were recovered at the Naconiche Creek and Boyette sites and it is likely that this pigment was used for body decoration.

|

The Lake Naconiche Woodland period archeological sites lie within the Mossy Grove Culture area.  |

Woodland period dart points from the Naconiche Creek site. Enlarge to see more information.

|

Goose Creek Plain pottery sherds found at Lake Naconiche sites.  |

Top to Bottom: Marksville Incised, Marksville Stamped and Indian Bay Stamped pottery sherds found at Naconiche Creek and Boyette.  |

At Boyette, in later Woodland contexts, the decorated sherds include primarily incised, punctated, incised-punctated, incised-rocker stamped, and rocker stamped elements.  |

Gary and Kent dart points recovered from Lake Naconiche sites.  |

Heavy duty chert cutting bifacial tools and gouges found at Lake Naconiche sites.  |

Heavy duty cutting bifacial tools and gouges made from ferruginous sandstone found at Lake Naconiche sites.  |

Flake tools used for scraping and cutting materials, such as bone and wood, found at the Lake Naconiche sites.  |

Early Friley and Steiner arrow points found at the Lake Naconiche sites.  |

Ground stone tools found at the Lake Naconiche sites include a grinding slab (top) and mano-- pitted stones (middle and bottom) |

|