|

We pick cotton like we did a hundred years ago and

we chop cotton like we did a hundred years ago, with

the exception that we put it into a sack now where we

used to put it in a basket.

-Fred Roberts, president, South Texas Cotton Growers

Association, 1920.

|

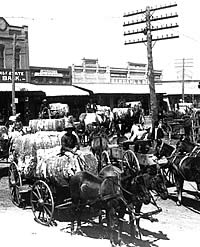

Cotton wagons on their way from the

gin to the cotton yard in Elgin. Photo courtesy of Leo

Foehner, Institute of Texan Cultures, University of

Texas at San Antonio. (Click to enlarge photo.)

|

Hoe found during excavations at the

Osborn tenant house.

|

Tenant families lived in one of four

houses on the Osborn farm during the heyday of cotton

farming there in the early to mid-twentieth century.

This house, shown shortly before its demolition in 1987,

was excavated by TxDOT archeologists. (Click to enlarge.)

|

Rows and rows of cotton stretch far

into the distance. Tenant farmers on the Osborn farm

planted in "halves": five rows for their family,

and five for the owner. Between 90 and 100 acres of

the total 327 acres on the farm typically were planted

in crops.

|

|

So at the end of the year, you pay the boss man

and you pay anybody else you owe… And my daddy

would say that money left his hands sore. He said, "So

much money went through my hands, that that's all I

have left, sore hands."

- Pete Martínez, Jr.

|

Samples of ca. 1930-1940s bottles

recovered during excavations at the tenant house. a,

"Vicks-Va-Tro-Nol 24" nose drops; b, "Bayer"

aspirin; c, "Gebhardt Eagle" chili powder.

|

Buttons for every occasion were recovered

from the tenant house and yard. Most date to the early

part of the twentieth century. a-c are celluloid buttons;

d-g, plastic (probably dating to 1945; h-l, glass; m,

collar stud. (Click to enlarge.)

|

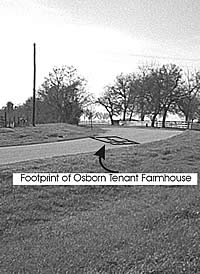

Today, nothing remains of the Osborn

tenant house. In this present-day view, the approximate

"footprint" of the house has been drawn over

a photo of the new road, Lovers Lane.

|

|

Cotton farming was vital to the industrial development

of Texas, and in Bastrop County it was one of the more lucrative

industries. But before the advent of mechanized harvesting,

it required hard, grinding labor to bring in a cotton crop.

Between 1840 and 1865, the work fell on the available pool

of African-American slaves. But after Emancipation and the

abolishment of slavery in 1865, cotton growers turned to tenant

farming as a means of securing the needed labor. The tenant

system was popular throughout the latter part of the nineteenth

century and into the first-half of the twentieth century.

In many instances, as was the case with T. C. Osborn, the

owner lived in town and allowed the tenant farmers to live

on and work the farm with little or no supervision.

During the late-nineteenth century, many of

the tenant farmers were former slaves, but in time many of

these workers left for better jobs in the developing cities.

This migration of farm workers and the growing demands of

the cotton industry caused a labor shortage that had to be

replenished.

At the turn-of-the-century, a reserve of low-paid

Mexican labor existed across the border and was an important

factor in the development of large-scale agriculture in south

and central Texas. Mexicans came by the thousands to work

on farms at wages of about $1.00 per day. In most cases, the

economic advantages afforded by employment in the U.S. pulled

Mexicans across the border, just as the violence and economic

disorder caused by the Mexican Revolution pushed them out

of Mexico.

Throughout the 1920s and well into the post-World

War II years, this large pool of agricultural workers made

cotton the premiere industry Texas, and the Mexican workers

the laborers of choice. Their labor was critical, because

modernization was slow in coming to the cotton fields. As

noted in 1920 by Fred Roberts, cotton farmer and president

of the South Texas Cotton Growers Association:

Modern machinery…has made it possible

for one man to cultivate a great deal of land, but there

has been no development along the line of picking and chopping

cotton. We pick cotton like we did a hundred years ago and

we chop cotton like we did a hundred years ago, with the

exception that we put it into a sack now where we used to

put it in a basket.

By 1920, 55% of all Bastrop County farms were

tended by tenant farmers, many of them Mexican Americans,

and the remainder by owner-operators. Within this system,

there were two types of tenant farmers: share tenants and

sharecroppers. The share tenant rented land and a house from

farm owners, and then cultivated with his own seed, equipment,

horses or mules, and made use of his family's labor. In contrast,

sharecroppers were resident laborers who were given a house

by the owner and received monthly cash advances to tide the

family over until the end of the season. Most sharecropper

agreements were for either halves or quarters. In Bastrop

County, most sharecroppers worked for halves.

As explained by Pete Martínez, Jr., a

former resident of the T. C. Osborn farm:

The way my daddy did it—all the time

I knew him, from the time I was born until the time he quit—the

landlord provided the land, the seed, and the mules and

plows. He furnished everything. The only thing you furnished

was your work. You and your family got out there and worked

for him.... When you go to harvesting the crop, you pick

a bale of cotton, you put it in the wagon, you bring it

to the gin, they'll gin it for you, they'll tell you how

much it brought you, you take that check to the landlord,

you get half of it.

See, you have to come up with quite a few

bales before you can get anything out of it, because all

during the year the landlord, he's advancing you money.

They had a deal where, depending on the size of the family,

they'd give you so much per month. And on the first of the

month you'd go up there and get your money.

Martínez recalled that the amount of

the monthly allowance was about $20. "Of course money

was different then," he said. "It was hard to get,

but it went a long way." Today, he continued, it's easy

to get, but it but it doesn't go very far.

His father-in-law, José Barrón,

sharecropped land near the Osborn farm. Barrón recalled

that his entire family, including his three brothers and three

sisters, pitched in to help on the farm whenever they could.

Their father was the planter, or sembrador, and the

children provided the labor during the harvest—piscaban

la cosecha.

In most families, children were taught to do

chores and hold small jobs early on out of necessity. Mrs.

Louise Rodríguez García recalls that she and

her four sisters helped in the fields from the time they were

five years old. She and her husband, David García,

and their children lived in the small Osborn tenant house

from about 1932 to 1941.

According to her daughter, Emma García

Rockwell, few sharecroppers could afford to hire people. Most

had to use the immediate family. People would get paid depending

on the amount, or weight, of the cotton picked.

If you had a bountiful crop, you might hire

people then, she said, but she couldn't recall her father

ever having hired outside help. "We, the families, had

to do it in order to keep the money within." She remembers

going into the fields by the time she was around seven or

eight years old, and she also took small jobs to help the

family make ends meet.

I went to school, but then I had to come

and help after school. Mother, like my grandmother, made

the clothes for us. My dresses cost 25 cents—2 ½

yards at 10 cents a yard. But 25 cents were not easily available.

I recall that canned milk was a must for my brother, Homer,

a baby in 1942. So I found a job washing dishes for a lady

who paid me 50 cents a week. I did this work en route to

school. It only involved about 30 minutes. The pay covered

the cost of the milk: 12 cans at 4 cents each.

The family had a milk cow and chickens and

also grew corn to supplement their needs. Mrs. Rockwell continued

helping in the fields for as long as her father had the farm

(ca. 1941). She was the first Latina to attend what

had previously been an all-Anglo high school and, after graduation,

she worked at nearby Camp Swift to earn enough money to attend

Southwest Texas State University. She eventually went into

the U.S. Foreign Service and worked in various embassies in

Europe and Central America.

The older generation, however, often found themselves

bound by the system, according to Pete Martínez, Jr.:

You see that's all the Mexican people did.

That's all they knew. You just got by. And you bought things—it

was just on a handshake back then. So at the end of the

year you pay the boss man and you pay anybody else you owe....

And my daddy would say that money left his hands sore. He

said so much money went through his hands, that's all they

have left, sore hands.

In spite of the hardships and hand-to-mouth

nature of the system, most sharecropper families showed a

strong work ethic, pride, and optimism. Martínez recalled

that his father's uncle, another farmer, was always a happy

man. He would say, 'Well, I don't have anything left, but

I've got my doors open.'"

See, what he's saying is that he paid

everybody, so he can go back and start charging from them

tomorrow if he wants to, because you see, his name was good.

He made good on that money he owed. See, that was the deal,

when my crop comes in, I will pay you. And they did.

Martínez's father moved off the Osborn

farm in 1954 after his son went to Korea. His uncles, the

Domínguez brothers, were the last persons in Bastrop

to sharecrop, finally quitting the system in the late-1950s

or early-1960s.

|

Cotton plants, shown in bloom in

late summer, typically are ready for harvest in fall.

Click images to enlarge

|

Weeding rows of cotton near El Paso

along U.S. 80. Photo courtesy of TxDOT and the Institute

of Texan Cultures, University of Texas at San Antonio.

|

Farms were worked mostly by hand

and with mule-drawn plows until the later half of the

twentieth century when mechanized equipment became widely

used. Photo courtesy Institute of Texan Cultures, University

of Texas at San Antonio.

|

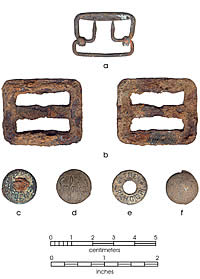

Metal suspender clasps and buttons

found in the tenant house excavations are reminders

of the heavy field clothing worn by the cotton farmers.

(Click to enlarge.)

|

In a state of dismal disarray, the

Osborn tenant house awaits demolition. (Click to enlarge.)

|

Children's toys and decorative beads,

recovered in the tenant house, are poignant symbols

of the pleasant family life recalled by several former

residents.

|

Cotton bolls, ready to harvest.

Photo by Mary G. Ramos, courtesy Texas Almanac.

|

Alta Vista cemetery in Bastrop, where

many of the Osborn tenants were buried. |

Cows graze where cotton once grew.

After tenant farming operations ceased in the 1950s,

much of the Osborn land was leased as pasturage for

cattle. Photo courtesy Ann Fellows Murphy.

|

|