Despite decades of discussion about best practices in radiocarbon dating, radiocarbon data remain frequently under-reported by many archeologists. Radiocarbon reporting should consist of much more than the radiocarbon ages and calibrated dates. Other critical pieces of information include descriptions of the sample material (exactly what was dated), archaeological context (precisely where the sample was found), pretreatment methods, and 14C measurement methods. These data are necessary to evaluate the relationship of the sample to the archaeological question it is intended to address. This section explains what kinds of information should be reported and why.

Essential Data

The most fundamental radiocarbon data for archeologists to report are the radiocarbon lab number, the sample material type, the radiocarbon age in radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP, also sometimes annotated as BP), and the δ13C, if it was included in the report from the lab. These are discussed below.

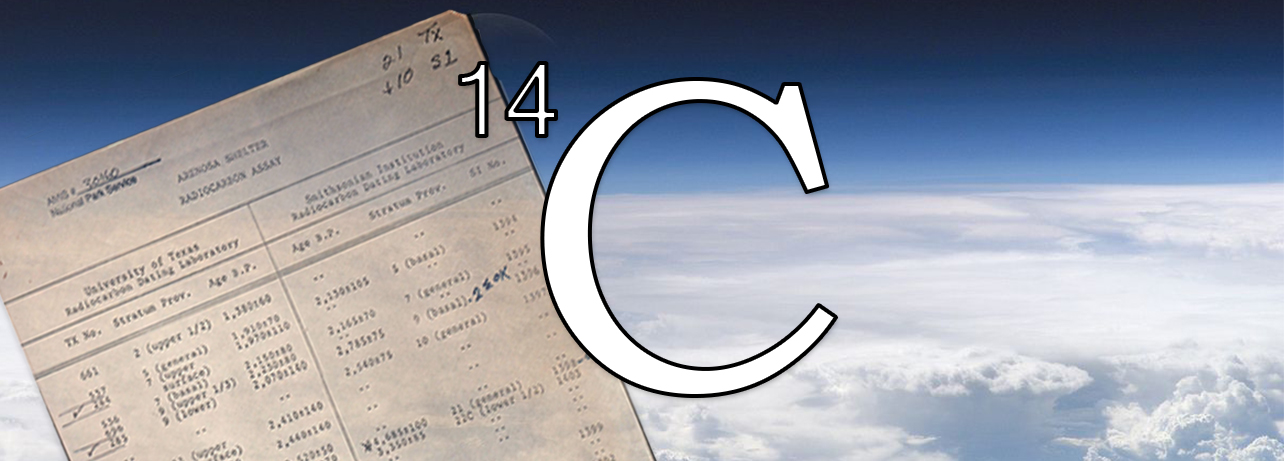

Laboratory number: The radiocarbon lab number is a unique number assigned by the measuring radiocarbon lab. This number makes the sample traceable, unlike specimen numbers assigned by the archaeologist which are often replicated across projects (for example, field specimen 1). Also, knowing where and when a sample was assayed can help future researchers determine how the sample was dated, even if that information wasn’t reported by the archeologist.

Sample material: The sample material should be reported as precisely as possible. The genus and species of the organisms should be reported, if known, as well as the floral or faunal part sampled. For example, rather than reporting "wood charcoal," or worse yet, merely "charcoal," a sample would be better reported as "carbonized Prosopis glandulosa (mesquite) twig." In this example, reporting that the assay was made on a twig (versus a piece of trunk) lets the readers know that the sample is on a relatively short-lived part of the plant and therefore the radiocarbon date is unlikely to suffer from the old wood effect. The old wood effect results from dating the older, inner rings of a long-lived tree species, thereby resulting in a radiocarbon date that could be decades or centuries older than the event of interest to the archeologist.

Measured vs Conventional

It is important to differentiate between measured and conventional ages. Measured ages are the raw ages as measured in the lab by AMS or other methods. In contrast, conventional ages (also called normalized ages) are measured ages that have been adjusted for isotopic fractionation. Some modern radiocarbon labs report both measured and conventional ages, though conventional ages are the most critical age to report for publication. Recall that legacy assays measured before the late 1970s were rarely corrected for isotopic fractionation, and so are usually measured ages. The radiocarbon date is different than either of these—the date is the calibrated conventional age.

Conventional radiocarbon age: The conventional age should be reported as an average and a measurement precision (also referred to as standard error) in radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP). It is standard to report the measurement precision as ±1σ (68% probability). For example, a conventional radiocarbon age may be reported as:

4130 ± 30 RCYBP (1σ)

Reservoir corrected ages, if applicable to the sample material, should not be factored into the conventional age but reported separately.

δ13C (delta 13-C) value (if reported by the lab): There are two different δ13C measurement types: that measured by isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) and reflective of the organism’s natural isotopic fractionation, and that measured by AMS, which measures fractionation introduced by the radiocarbon dating process and natural processes together. For an explanation of isotopic fractionation, see In the Environment. IRMS δ13C values are useful for dietary studies and should be reported if they are measured. In contrast, AMS δ13C values are typically not reported, but they are used to calculate conventional ages and can be obtained from radiocarbon labs upon request. It is important to understand that AMS δ13C values are not useful for dietary studies.

Radiocarbon measurements made before the late-1970s were usually neither measured for δ13C nor adjusted for isotopic fractionation, despite fractionation being a known issue since the 1950s. Fortunately, estimated δ13C values can be applied to legacy ages if the sample material type is known.

Because of the complexities of δ13C reporting through time it is all the more important for the archaeologist to understand what is being reported to them by the lab, and make clear what kind of δ13C data is being presented in their own publications: IRMS or AMS δ13C, or estimates based on material type (in the case of legacy dates).

Other Important Data

Calibrated Date: It may seem surprising, but the calibrated radiocarbon date is not as essential to report as the conventional radiocarbon age. The calibrated date is less important to future researchers because it cannot be recalibrated with new calibration curves, while the conventional age can be. That said, calibrated dates are necessary for discussions of the timing of archaeological events, and so are typically reported by the publishing archeologist. See In the Environment for a discussion of calibration.

Calibrated dates should be indicated by using either cal BP, cal BC/AD, or cal BCE/CE. The radiocarbon date should, like the radiocarbon age, be reported with its measurement precision as discussed in Dating 101. Either ±1σ (68%) or ±2σ (95%) may be reported so long as it is stated which is being used. The calibration curve used to calculate the date should also be reported and cited in a bibliography or references cited list. It is standard for radiocarbon dates to be reported as an age range, rather than a mean and standard error. For example, a calibrated radiocarbon date may be reported in this format, or variations of it:

647-555 cal BP (2σ, IntCal20)

Often, radiocarbon dates are reported in a table, and the measurement precision and calibration curve are commonly indicated in the table header or a footnote.

Method and Context: Methodological and contextual information are critical for interpreting how these data address the archaeological question of interest. This type of information includes the method of measurement, pretreatment processes, and any information pertaining to sample condition. For example, if the sample is suspected to have contamination from conservation treatments such as the application of consolidators or binders like shellac or glues, that would be an important thing to report, as well as any steps taken to remove the conservation treatment prior to dating.

Contextual information should include a site name and number, intra-site provenience such as the associated stratum or feature, and when the sample was collected and submitted for radiocarbon dating and by whom. Additionally, why that sample was chosen (rationale for selection and the targeted research question the sample was intended to address) and the sample’s contextual relationship to the research question should be discussed.

Reporting Summary

Radiocarbon data should be rigorously reported for several reasons: for data transparency and to allow for evaluation of the reporting archeologist’s interpretations; for traceability of the radiocarbon assay across publications, back to the laboratory and potentially even the curation facility where extra sample material may be stored; and to allow future archeologists to recalibrate radiocarbon ages when new calibration curves are released, to build upon past work, and to apply radiocarbon data to new research questions. On occasion a reporting archeologist may find that they are constrained in the amount of text they have in a publication and are not able to report more than the essential data for each radiocarbon assay. In this situation, the radiocarbon information may be more fully reported in supplementary materials available for digital download, or simply published elsewhere and referenced.