Spanish Colonial expert Anne Fox

from the University of Texas at San Antonio helped confirm

the identification of the mission.

Click images to enlarge

|

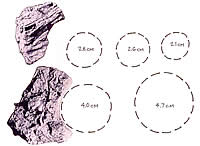

These pieces of melted lead from

the mission provide evidence of the fire that burned

the buildings down. Records and inventories indicate

that there were several soldiers stationed at the mission

to provide protection. They had lead with them for making

musket balls. Juan Leal was one of these soldiers.

|

In this shallow archeological unit,

excavated out in the alfalfa field, a layer of lighter

soil at the top of the excavated surface indicates the

plow zone. This is the layer of soil turned over each

time the field is plowed or disked. Much of the original

deposit containing remains of the mission had been disturbed

by farming activities over the past century. Hall estimates

that, with another 20 years of plowing, all original

remnants of the mission, such as filled pits and post

stains, would have been destroyed.

|

|

All in all, the archeological findings at the mission

suggest that the depiction of the mission in the Terreros

mural is fairly accurate.

|

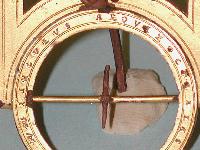

Close up of the universal equinoctial

sundial. It was half of a two-part navigational instrument.

The missing part is the compass upon which the sundial

sat. Photo by Donny Hamilton.

|

Archeologist Elton Prewitt uncovering

the sundial.

|

Hand-wrought nails and spikes.

|

Musket balls.

|

Gunflints and Guerrero arrow point.

The Indians were completely dependent on Europeans for

muskets, lead shot, and gunpowder. One thing they could

make for themselves, though, were the gunflints needed

to ignite the powder when a musket was fired. Some examples

of so-called "native" gunflints are shown

here, along with an unstemmed arrow point of the type

that Texas Indians made during the time they were in

the Spanish missions.

|

Post stain. By mapping all of the

burned post stains found at the mission, we were able

to trace the outlines of the stockade and the houses

and church inside.

|

|

Following the initial discovery of the mission

in September of 1993, Grant Hall, Kay Hindes, and Mark Wolf

organized a testing program funded by the Texas Historical

Foundation, the Lende Foundation, and Bob and Kathleen Gilmore.

Testing of the site was done in late 1993 and early 1994 by

Hall, with the assistance of students from Texas Tech University

and various archeological colleagues. Spanish Colonial expert

Anne Fox from the University of Texas at San Antonio lined

up a group of metal detector operators, all members of the

Southern Texas Archeological Association. Led by Tommy Tomesal,

this group used the detectors very productively to locate

a number of musketballs, nails, brass artifacts, and other

Spanish artifacts across the mission site. The location of

each item was carefully plotted on a map.

Test excavations scattered around the site revealed

that much of the original soil deposits and land surface upon

which the mission was built had been cut away or churned up

by farming activities on the land from about 1900 up to the

present. At first we feared that all signs of the mission

had been completely destroyed by plowing. Fortunately, as

testing progressed, we began to find stains representing the

posts used to build the mission stockade, church, and other

buildings. These stains, consisting of ash, charcoal, and

burned soil, marked the spots where wooden posts had burned

down into the ground. The wood itself was gone, but the ash

and charcoal showed where each post had been, and gave us

its approximate diameter.

The test excavations carried out in 1993 and

1994 verified that the site was indeed that of Mission San

Sabá. Though heavily damaged by plowing, there was

still buried evidence in Judge Lyckman's alfalfa field that

could tell a good bit about the configuration of the mission.

But this would require a major excavation and that meant we

needed support. This is often the most difficult obstacle

to overcome for archeologists undertaking pure research projects

and it is something many people don't understand. Major archeological

investigations, even if done with the assistance of volunteers

and students, are time-consuming and costly. A proper investigation

involves a lot more than digging. It takes specialists in

many fields working before, during, and after the excavation.

And the responsibility of the lead investigator is not completed

until a full scientific report is published.

1997 Dig

In 1997, with funding from the Summerlee Foundation

and other benefactors, Texas Tech archeologists returned to

the mission for a full-scale excavation. Once again the team

included a mix of professional archeologists, students, and

volunteers. Realizing the upper soil deposits were churned

by farming, the decision was made to use a small trackhoe

to strip off the disturbed soil. Once this "plow zone"

was removed, we quickly were able to locate and excavate the

post stains and features lying beneath. This approach proved

to be very effective in exposing roughly 100 post stains and

about 30 archeological features. Along the south side of the

field, a narrow strip of the original ground surface was preserved,

protected by a fence line. There, careful hand excavations

took place.

The post stains, when plotted out on a map,

revealed a trapezoidal outline shape to the mission stockade,

with the broad end to the west. This side was about 160 feet

in length. The north wall, clearly visible, was about 130

feet in length. The east and south walls of the stockade were

not as easy to make out. However, we speculate that the east

wall was shorter than the west, and ran parallel to it. The

south wall was probably the same length as the north wall.

Within the stockade, we found post stains that

we think represent the church. These defined a building oriented

with the long axis east-west, having dimensions of roughly

35 by 50 feet. The belief that this was the church is supported

by the fact that it was out in front of the traces of other,

smaller buildings. Lead musket balls were concentrated around

it, consistent with the stand that Juan Leal and the other

survivors made in the church. The Indians appear to have fired

many musket shots at the defenders within the church. Another

find was that of an empty grave at the west end of the stains

representing the church. All that was found in this grave

were a human finger bone, a couple of teeth, and a number

of green-glass seed beads. We assume that the body the grave

once contained was disinterred and removed to another location

following the 1758 attack.

Along the south wall, on the inside of the stockade,

were post stains representing at least five small buildings.

The largest measured about 14 feet in width and 20 feet in

length. These were probably the house of the priests and soldiers,

storerooms, and kitchens. All in all, the archeological findings

at the mission suggest that the depiction of the mission in

the Terreros mural is fairly accurate.

In addition to the empty grave associated with

the church, there was another particularly interesting feature

found in what would have been the northwest corner of the

stockade. This was a pit that contained quite a few oxen bones,

horns, and horn cores. The survivors of the attack said that

the Indians killed all of the livestock at the mission. Later,

they roasted and ate the meat of the oxen. We think this pit

containing the oxen bones was the barbeque pit where the Indians

did their cooking to celebrate their victory.

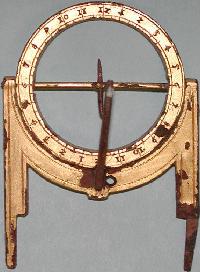

Amid the bones in the barbeque pit, we made

a most unexpected and unusual discovery—that of a small

gold-plated brass pocket sundial bearing the date 1580, some

177 years before the sacking of the mission. This artifact

is one of the earliest scientific instruments of its type—a

universal equinoctial sundial. This sundial was once part

of a two-part navigational instrument. The missing part is

a compass upon which the sundial sat. How this specialized

and rare item found its way to Mission San Sabá and

into the pit with the cattle bones is a complete mystery.

It was obviously a heirloom item, one that must have belonged

to a well-to-do person. Given its striking appearance, it

seems odd that the Indians didn't carry it off. Perhaps it

was lost amid the celebration.

Another mystery remains concerning the mission.

When the Spanish soldiers returned to the scene of death and

destruction several days after the attack, they buried the

two priests and several other men who had been killed and

burned in the Holy Ground by the church. These graves still

have not been found. A couple of explanations come to mind.

Since the bodies were badly decomposed, the graves may have

been dug quickly and were therefore shallow. They may well

have been destroyed by farming in the twentieth century. A

second possibility is that the bodies were later disinterred

from the graves and taken to the San Sabá Presidio

cemetery, or perhaps back to Mexico. This latter explanation

is consistent with the finding of the emptied grave and seems

the most likely.

The Indians who attacked the San Sabá

Mission in 1758 were unusual for their time in that they were

equipped with firearms, swords, armor and other European weapons.

They obtained these from the French, who then occupied Louisiana

and had hopes of taking over Spanish territory in Texas, in

exchange for buffalo, deer, and other hides and furs. The

French knew that the Indians would use the firearms against

the Spaniards. When the Indians attacked the mission, it was

the first time that the Spaniards had come up against a force

of Native Americans armed with muskets. The many lead musket

balls found at the mission were concentrated in the area of

the site where the church had been. This was the building

where Juan Leal and the other survivors had held out until

nightfall, when they escaped the burning mission and made

it to the safety of the presidio. It is easy to imagine the

Indians circling the church (at a safe distance, because Juan

Leal and the others were firing their muskets at the Indians)

and firing musket shots into its walls in hopes of killing

the Spaniards within.

Spanish pottery.

|

Tommy Tomesal, leader of a group

of metal detector operators, all members of the Southern

Texas Archeological Association. Tomesal's group used

their metal detectors very productively to locate a

number of musketballs, nails, brass artifacts, and other

Spanish metal artifacts across the mission site.

|

Some daub specimens allowed us to

calculate the diameters of wooden poles that formed

the walls of the buildings inside the mission.

|

Dr. Kathleen Gilmore at the San Sabá

Mission in 1993. A noted authority on the Spanish colonial

era in Texas, she was the first to search for the location

of the mission in the mid-1960s. Her work served as

a foundation for all later efforts to find the mission.

|

This dark-stained area was either

a cooking pit or trash pit containing animal bones,

burned rock, and other debris relating to life in the

mission, prior to the attack. A surprising find amidst

the other bones was a fragment of a human cranium, which

is being pointed out in this photograph. It is a mystery

as to why human skeletal remains would be found in this

feature.

|

Gold-plated, brass pocket sundial

bearing the date 1580 found in a barbeque pit amid the

bones of oxen slaughtered and cooked by the victorious

Indians. This rare and extremely well preserved artifact

was conserved by Dr. Donny Hamilton of Texas A&M

University who reports that the brass alloy had a high

percentage of copper. Photo by Donny Hamilton.

|

View west of 1997 excavations. Pink

flags mark post stains and foundation trench lines of

six small houses built within the stockade on the south

side of the mission compound. The trackhoe, the machine

used to removed the plow zone, is visible on the right.

|

Glass beads. The Spanish priests

brought hundreds of necklaces made of green and blue

glass beads to give to the Indians. These beads were

manufactured in Europe. Following the attack on the

mission, the Indians carried away many of the necklaces,

but quite a few of the beads were scattered around the

site to be found by archeologists.

|

Another authority on the Spanish colonial

era in Texas, the late Curtis Tunnell visited the San

Sabá Mission excavations in 1994. Tunnell conducted

excavations at the site of Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa

Cruz, located about 90 miles south of San Sabá

on the Nueces River near present-day Camp Wood, Texas.

Following the failure of the San Sabá Mission,

the Spanish priests and soldiers learned that the Apache

Indians would be more likely to live in a mission in the

more familiar Nueces River country. Nonetheless, Mission

San Lorenzo also ended as a failure, albeit not in as

spectacular a fashion.

|

|