The Schild Ledger Book: Drawing a Culture in Transition |

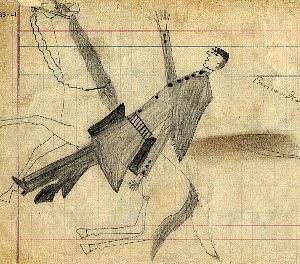

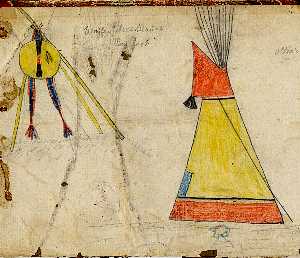

In this enigmatic scene, a mounted warrior wearing a long feather headdress with horns and carrying a feathered shield and spear rides alongside a wounded warrior apparently falling from his horse. An additional shield and trade era Leman rifle are drawn in the top right corner, and hoofprints mark the path of the two riders. It is unclear whether the wounded man is a comrade being rescued or a victim. The note at top in German reads, "Wounded Indian falls from horse;" the bottom note reads, "Black snake, Cheyenne." The drawing is from the Schild Ledger Book, comprising nearly 60 Plains Indian drawings by one or more artists. Based on a variety of clues, the drawings are thought to have been created sometime between 1875 and 1895. TARL Archives. |

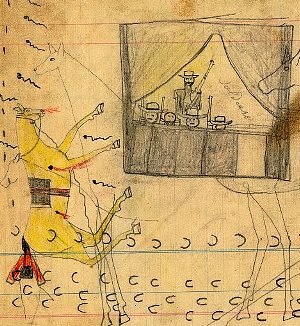

Indian attack on U.S. soldiers, who are barricaded within a hole or depression in the ground. In this richly detailed, panoramic scene, four soldiers and six Indian men are depicted. The Indians are armed with feathered lances and rifles, and two of the warriors wear long, feathered war bonnets. The label at bottom right reads, “A heavy battle in which more white than Indians killed. Soldiers in hole” and “Fight where half Indians killed.” Based on the position of the soldiers as well as their uniforms, Texas Historical Commission archeologist Brett Cruse believes this scene may depict the Buffalo Wallow battle in 1874, one of several clashes between Southern Plains Indians and the U.S. Army during the Red River War. There are few reported accounts of battles where soldiers have fought from a defensive position dug in within a hole. An unusual element in this drawing is the suggestion of a wooded landscape in the top left corner. Trees, plants, and geographic features are rarely included in ledger art. TARL Archives. |

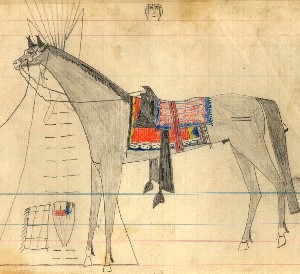

Following the TrailThere are, however, numerous other clues in the drawings—elements of Indian dress, weaponry, and ornamentation of horses, as well as details of customs depicted. Some of these apparently connect them to Kiowa and others, although fewer, to the Cheyenne. Prominently featured in almost every drawing are horses, a critical element in the development of Plains Indian culture, enabling tribes to hunt buffalo with greater ease, travel farther, carry heavier loads, and conduct warfare from a mobile base of operations. Many of the horses are drawn with elaborate bridles and other ornamentation, as well as body paint, signifying their importance to the tribe. Some bear brands indicating they may have been obtained through raids on white settlements or Army posts. Stylistic details may hold clues to the artist(s) or to the evolving nature of the art form: while most horses in the Schild book are drawn with a diminutive head in relation to the elongated body, a few are shown with more realistic proportions. Variations in the way horses are depicted in motion—most are in "rocking-horse" style with back legs extended, but a few are drawn with a rear leg thrust forward—suggest the hands of multiple artists. Great attention is paid to details of dress, both of the Indians as well as the U.S. soldiers and settlers, and these details may help in dating the drawings. Cartridge belts and uniform jacket style suggest the post-Civil War period, not the 1840s, as stated in the notes attributed to the Tips family. Some soldiers wear the post-Civil War kepi style forage cap, while others wear brimmed hats. Native equipment—shields, headdresses, lances, and other personal gear—was drawn in sufficient detail to identify the Indian subjects to their cohorts at the time. As in other ledger artwork, some of the Schild battle drawings include the symbolic use of hoofprints and dashed lines to represent directionality and movement, and spiral lines with dots to represent bullets in flight. Like earlier, traditional hide paintings, most Schild ledger scenes convey a sense of narrative by drawing action from right to left, or with horses and figures largely drawn in left profile. Landscape details are not included, with the rare exception of the panoramic battle scene in which what appears to be a motte of trees or woods in the top left corner. The most comprehensive research on the Schild ledger drawings was conducted by University of Texas Fine Arts student Barbara Ellen Loeb LaMont. Her 1975 unpublished Master’s thesis compiles interpretations of tribal iconography and regalia derived from correspondence with Plains Indian scholars, art historians, and ledger art experts across the country. These include Father Peter Powell, author and spiritual director of the St. Augustine Center for the American Indian and a member of the Chief’s Society for the Northern Cheyenne People; Kiowa artist James Auchiah, one of the famed “Kiowa Five” at the University of Oklahoma’s School of Art in the 1920s; Smithsonian Institution anthropologist and author John Ewers; traditional Indian costume maker Mildred Cleghorn; and UT Anthropology Professor William Newcomb, the latter of whom was instrumental in acquiring the drawings for the TMM. LaMont also examined collections of ledger drawings at other institutions, including those of the Smithsonian National Anthropological Archives, comparing the Schild drawings with those of known Kiowa and Cheyenne artists. Given the authoritative sources she consulted, LaMont’s thesis is a fascinating trove of information. Excerpts from her findings and those of other researchers are included with this selection of examples from the Schild Ledger book. Enlarge each drawing below for detail:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This detailed drawing, interpreted as “bringing boughs to the Sun Dance Lodge,” holds promise as identifying a specific tribe or culture. A mounted Indian man rides behind a group of people under umbrellas who appear to be pulling felled trees. The lodge is framed by upright poles or forked tree trunks and is adorned with feathers and bundles of goods (possible offerings). The long black object atop the lodge is thought to represent a stuffed buffalo skin which many tribes placed above the center pole. Although identified in the German label as “Indian burial”, the structure and boughs are thought to identify it as a Sun Dance Lodge. Father Peter Powell identified the scene as Kiowa because women of that tribe, unlike Cheyenne, assisted in bringing boughs to the lodge. However, the center pole appears to have a red stripe of paint, which some scholars believe was not a Kiowa tradition; most Kiowa lodge center poles were not painted. TARL Archives.

|

Ledger Art in Historical ContextUnlike calendar art, or winter counts, executed by Kiowa and Lakota men using simplified symbols to mark key events within the tribe over the course of a year, many ledger drawings are personal narratives heralding individual deeds and honors. The warrior-artists recorded their heroic past and the tumult and transformation of their life in the present. Ledger drawings memorialize the “glory days” of warriors and hunters, when bison were still abundant on the Plains, while other scenes capture moments of individual bravery during battles with the U.S. Army before the tribes were moved onto reservations. According to Candace Greene, author and North American Indian ethnologist at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, the Kiowa considered these heroic actions, or coups, to be the “property” of the man who executed them. The right to tell the story or portray it in drawing was closely held by the individual. In some detailed drawings, Greene has found that specific individuals can be identified, based on details of their dress and weapons such as the symbols on their shields. Other ledger drawings record tribal customs, such as courting, dances, and spiritual ceremonies. For the artists, the drawings were important representations reflecting a chief or warriors’ wealth and status, signified by the quantity of possessions and the ornamentation of regalia and weaponry. Representing the continuation of an artistic tradition originally executed on buffalo hide robes and tipi covers, the drawings are a colorful and poignant reflection of Plains Indian life. Greene examined copies of the Schild ledger drawings and, in a 1984 letter to a TMM staff member, wrote that in her opinion “the drawings represent the work of several artists and are definitely not by any Cheyenne artist whose work I have examined. Their style is not typical of the Cheyenne, especially the extensive use of square front and back views… .” She notes further that the style is more typical of the work of various artists located around Ft. Sill, the most well known of which are Kiowa. The representation of costume by the artists also suggests Southern Plains. Although she notes there was much intertribal sharing of costume styles during the late 19th century, her interpretation as a whole contradicts the handwritten notes in the Schild book which seem to connect the drawings to a location in North Dakota. Much of known Plains ledger art was created during a time of tremendous cultural upheaval during the 1860s-1880s when contact with white soldiers and settlers led to violent conflict and ultimately removal of tribes to reservations. As a result of the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1868, and the Red River War of 1874-1875, the Kiowa and Comanche were concentrated together on a reservation in western Indian Territory, now southwestern Oklahoma. Cheyenne and Arapaho were confined on a different reservation in the same general area. The latter tribes drew their annuities (supplies furnished annually by the U.S. government) from Camp Supply, and later from Fort Reno. Kiowa and Comanche drew their annuities at Fort Sill. Members of all four tribes participated in the battles comprising the Red River War, which occurred in the wake of the attack on white buffalo hunters at a compound known as Adobe Walls, in the Texas Panhandle. The battle of Buffalo Wallow, believed to be depicted in one of the ledger drawings, was fought on September 12, 1874, in southeastern Hemphill County, Texas. Of all the ledger art known to have been created by members of the various Plains tribes, some of the most vivid scenes are attributed to Kiowa men held prisoner at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. At the end of the Red River War in Texas and Oklahoma in 1875, more than 70 Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Caddo men were transported to the prison without trial and placed under the command of a man named Richard Pratt. While the intent of the imprisonment was to strip the Indians of their culture and force assimilation into American life, it was Pratt—with his philosophy of ‘kill the Indian and save the man”—who encouraged the prisoners to create works of art as a trade. Many of the drawings were sold commercially to an eager tourist market. Denied their traditional way of life, the artists preserved their past through drawings. An Enduring MysteryThe Schild Ledger Book was passed down through at least three families before it came to the University of Texas. Memories and interpretations, whether orally transmitted or written, are subject to alterations with each retelling or reiteration. Because the Comanche loomed large in the history of Fredericksburg, Texas, where Herman Schild and the Tips family lived at one time, it is possible that the art was attributed to that tribe simply because of that aspect of regional history. The notes accompanying the drawings are puzzling, and questions about the artists and people and places depicted in the drawings may never be definitively answered. Later analyses of the Schild book were conducted long before museum collections and government records were digitized and made available through the Internet. There now is considerable opportunity for researchers to learn more about the remarkable Schild drawings by comparing them with other collections available online and for questions surrounding their provenance to be re-investigated. Correlated Lesson Plan for Teaching about Plains Ledger ArtA new lesson correlated to the Schild Ledger Collection examines how ledger art was, and still is, an important medium of expression for Native Americans. Created by TBH Education Advisor Carol Schlenk, the lesson is oriented to 7th-grade students and meets a number of the state-mandated curriculum objectives for Social Studies and Middle School Art (Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS). Detail on this lesson and a link to the TEKS and pdf copy of the lesson is below: Drawing Our Lives: Plains Indian Ledger Art Revisited Credits and SourcesThis Spotlight entry was written by TBH Editor Susan Dial, based on information in the following sources as well as research on additional ledger drawings and correspondence in TARL Records. TBH Associate Editor Heather Smith programmed the page for the web. Scans of the images were made by TARL volunteer Marianna Grenadier. The Schild Ledger Book is owned by The University of Texas and curated at TARL.

Ewers, John

Greene, Candace S.

LaMont, Barbara Ellen Loeb

Mooney, James (Transcribed and edited by Father Peter Powell) Utley, Robert M. LinksTo learn more about the Kiowa and view additional examples of ledger art, see the Kiowa section of the Peoples of the Plateaus and Canyonlands in Historic Times on TBH: http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/plateaus/peoples/kiowa.html Learn more about the last days of the Plains Indians in Texas in The Passing of the Indian Era in the Frontier Forts exhibits on TBH: http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/forts/indians.html Learn more about the Battles of the Red River War, the 1874 U.S. Army campaign to remove tribes from the Southern Plains: http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/redriver/index.html. Other ledger art collections can be viewed at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History galleries of works by Fort Marion artists: http://anthropology.si.edu/naa/exhibits/kiowa/ft_marion.htm

|

|