Artistic Expression |

|

|

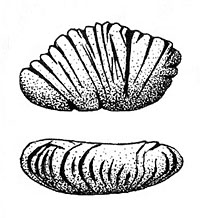

Necklaces or strings of bone artifacts were found in burials at the

Morhiss site in Victoria County. On the left, nearly 100 adult rattlesnake vertebrae were

strung on a cord.. At right, hollow bird bones were grooved and snapped to form beads. Insets

in center show close-ups of the rattlesnake vertebrae (top) and a bird bone bead, comparable to

those on the necklace. TARL collections. |

|

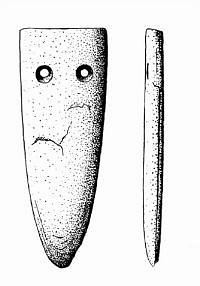

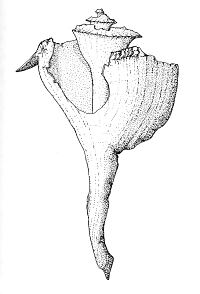

Ornaments and Decorated Objects - "Portable Art"In contrast to rock art, comparatively numerous examples of ornaments and decorated objects fashioned by native peoples have come from archeological sites across the South Texas Plains. These run the gamut from bird-bone beads to tubular smoking pipes carved from stone and decorated with geometric designs to smooth pebbles adorned with painted or engraved designs. Some of these items accompanied burials at cemetery sites and clearly represent grave offerings that had special meanings to the deceased and their loved ones. Ornaments-or what we today might call jewelry-include pendants (or gorgets), and beads made of shell, bone, and stone. At the Morhiss site, a small cemetery in Victoria County, archeologists found two strings of beads-apparently necklaces. One was made of hollow bird bones which had been grooved (incised with a sharp stone tool), then snapped into smaller sections which were then smoothed and polished to form finished beads. The other "necklace", placed in the burial of a male, was made of dozens of vertebrae from adult diamondback rattlesnakes. Given the placement of this artifact at the knees of the deceased, it may not have been a necklace. But the vertebrae were obviously strung together and apparently worn from use; perhaps the string of snake vertebrae was attached to a leather garment or bag. Freshwater mussel (clam) shells, with their gleaming opalescent interiors, were favored materials for prehistoric artists. Cut and shaped into various forms, the shells became pendants, beads, or "danglers" which were strung on a cord through small drilled holes. Pendants frequently were decorated with designs, including intricate geometric patterns and punctations. Marine shells, especially the Lightning Whelk (Busycon perversum pulleyi) and several other species of conch shells, were also worked into ornaments and are sometimes found whole as well far from the coast. The large spiraling conch shells were highly valued by the native peoples of the South Texas Plains (and far beyond). This value can be seen by the elaborate shapes into which conch shell pieces were carved, by the diverse range of ornament forms into which they were fashioned, and by the fact that conch shell artifacts are commonly left as grave offerings. Given its prehistoric importance, it seems most appropriate that the Lightning Whelk is now the official Texas State Shell. In prehistoric times, conch shells were often used by coastal peoples to fashion everyday tools such as gouges, scrapers, dippers, and perhaps small bowls. But the shells traded or carried inland seem to have been used almost exclusively as ornaments and symbols. Lightning whelk shells were used in two particularly striking ways. Broad cup-like sections of the outer shells were shaped into ovals pendants or gorgets (chest pieces) suspended from cords around the neck. Some conch gorgets have elaborately carved or drilled designs. The other section of the lightning whelk shell that was often used is the central axis or columela. Drilled through and suspended in a dangling fashion, these long, pieces, sometimes left with visible spirals, sometimes smoothed to tubular shapes, would have been quite distinctive. Small stones and smooth pebbles also caught the eye of native artisans looking for available craft materials. Flat pebbles were used as is and sometimes even shaped and ground along the edges to create elongate triangles, rectangles and other shapes. Some had holes drilled through one or both ends, transforming the stones into pendants or other ornaments. Other pebbles were left whole and had painted designs. Painted and or sometimes engraved pebbles are common in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, but they do occur on the South Texas Plains. Technically, these stones fit within the size range known to geologists as cobbles, but archeologists call them pebbles. These are stream-worn stone pebbles (cobbles) that are small enough to be held comfortably in your hand. They are usually fairly flat rocks that are oval or elongated in outline shape. Shaped by nature, they quite purposefully chosen hard, thin limestone pieces of the sort commonly found in gravel bars along the streams and rivers that drain the Edwards Plateau as well as along the middle stretches of the Rio Grande. Although rare, painted pebbles are known from the South Texas Plains, especially in the northwestern part of the region where the raw materials (smoothed pebbles) can be found in many streambeds. This apparent scarcity is probably attributable mainly to poor preservation conditions - painted designs seldom survive in open archeological sites. Even in the dry rockshelters of the Lower Pecos archeologists sometimes fail to notice the often-faint traces of designs. The meanings of the painted pebbles are debated, but archeologist Mark Parsons has argued that these are representations of human beings, some more abstractly than others. Some examples from the Lower Pecos clearly depict humans. A much different design was executed on a tiny, oval-shaped pebble found on the surface along San Miguel Creek in Atascosa County. Although there was no obvious evidence of shaping by pecking or grinding, a series of deeply engraved lines on all surfaces seems to give the artifact the appearance of a shell. |

|

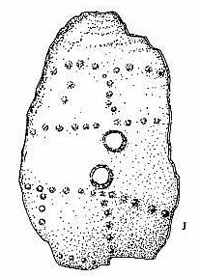

Prehistoric artists transformed marine shells (likely Lightning Whelk) into beautiful ornaments. The specimens shown—gorgets (chest pieces) from the Olmos

Dam site in San Antonio—have been decorated with small punctuations drilled in geometric patterns.

The cross design is an intriguing motif that occurs widely in native America; these examples are

thought to date over 2100 years ago (before 100 B.C.). Photo courtesy Thomas R. Hester. |

|

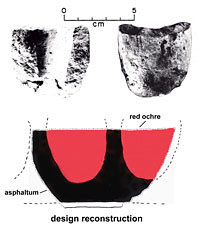

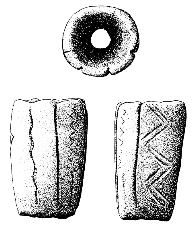

Native peoples also engraved designs on bone tools and other objects, such as awls and hair pins, as well as carved stone smoking pipes, although the latter are quite rare. Several decorated pipes have been reported as surface finds along the lower Rio Grande. The example shown is of fine-grained sandstone with deeply incised designs, varying from wavy to zig-zag lines, running the length of the object. Another pipe fragment, found at the Hinojosa site in Jim Wells County, is even more unusual. The short, cylindrical fragment of a sandstone pipe bears traces of a bold curvilinear design executed in red ocher and black asphaltum (natural tar). Although recovered from the surface of the site, the sandstone pipe is attributed to a Late Prehistoric artist. Some of the most remarkable traces of prehistoric artisanship can be found on bone objects used as tools, ornaments, and even musical instruments. Most bone tools aren't decorated, but some pointed awls (weaving tools?) and needles do have incised designs. Curving, flattish bone pieces thought to be hair pins often have intricate incised designs in checkerboard patterns and spirals. There are also examples of incised rasps or bones that have sets of deeply incised parallel lines that produce a rhythmic sound when rubbed with a stick or another bone. One final, most peculiar type of bone ornament is worth mentioning - decorated sections of bone fashioned from human bones. These are rare and known mostly from along the Rio Grande. It does not take any imagination to suggest that such objects had special ritual significance - perhaps these were made from the bones of enemy peoples. |

|

|

|

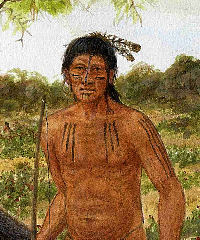

Rock ArtAlthough bedrock bluffs and overhangs are rare throughout most of the South Texas Plains, there is surviving evidence in the northwest portion of the region that native peoples took advantage of these natural "canvasses." Sites with painted rock art panels, Pictograph sites, are very rare in the region for the reasons noted above. The Old Sullivan Springs site (41WB56) in northwestern Webb County is one of the few documented examples known in the region (other pictograph sites are known from adjacent northeastern Mexico). The pictograph panel at Sullivan Springs measures roughly 13 feet (4 m) wide by nearly 5 feet (1.5 m) high in some areas. The painted designs were executed in shades of red and yellow on a wall beneath a sandstone overhang overlooking the Rio Grande River. The motifs are largely vertical zig-zag designs, although there is a central anthropomorphic figure with what may be a horned headdress. The figure appears to have both arms extended and wears a horned headress. Archeologist Thomas R. Hester, who recorded the site, notes its proximity to a large spring that is associated with several nearby campsites, one of which also contains several bedrock mortars and grinding surfaces - modified bedrock with an obvious utilitarian purpose. According to Hester, visitors to the site in the mid-20th century recalled seeing smaller rock art panels nearby; these may have been destroyed since by floods and weathering. Body ArtEarly explorers traveling through south Texas occasionally made note of the appearance and customs of native peoples, including the often elaborate tattooing, painted designs, and piercings with which they ornamented their bodies. Although there clearly were different reasons for ornamenting the body, including ritual painting for ceremonies and raids, or tattooing to denote group affiliation, these adornments were a form of artistic expression. There are several accounts of the body art of the Coahuiltecan groups of south Texas. In Cabeza de Vaca's journal, La Relación, we learn that the Yguazes, a sub-group of the Coahuiltecos, "have both a nipple and lip bored." Tattoos were common on Coahuiltecan men and at least some of the women. Coahuiltecan boys were tattooed during ceremonies marking the passage from childhood to adulthood. Herbs were rubbed on to numb the skin, then shallow incisions were made with sharp flakes or animal teeth. These cuts then were rubbed with charcoal and resin. Captives were often tattooed as well. Fernando del Bosque noted that a Spanish boy brought to him by a Gueiquesale Inidan had "a line on his face marking him from his forehead to his nose, and two lines on his cheeks, one on each, and rows of them on his left arm and one on the right." |

|

SourcesBlack, Stephen L. Chandler, C. K. Chandler, C. K. Chandler, C. K. and Cheryl Lynn Highley Chandler, C. K. and Don Kumpe Hester, Thomas R. Krieger, Alex D. Martin, George C. (Editor) McClure, W. L. Newcomb, W. W. Taylor, Anna Jean and Cheryl Lynn Highley |