Historic Camps and Crossings on the Medina and San Antonio Rivers

Spanish explorers traveling toward the area of modern-day San Antonio made note of numerous encounters with native peoples, particularly along rivers and at established river crossings below the rugged Balcones Escarpment. On the Medina and San Antonio rivers, they identified a number of ethnically distinct bands or groups who spoke a similar dialect and shared similar lifeways, including the Payaya, the Pastia, the Pampopa, the Sijame, the Cauya, the Semonam, the Saracuam, the Pulacuam, and the Anxau. A number of other groups such as the Sulujam and the Mesquite were known to have been on the San Antonio River.

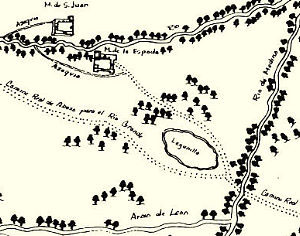

Late 17th- to early 18th-century entradas led or accompanied by men such as Alonso de Leon (1686-1690), Fray Damian Mazanet (with de Leon in both 1689 and 1690, and Teran in 1691), Don Domingo Teran de las Rios (1691) Espinosa, Olivares, and Aguirre (1709), and others, enountered aboriginal groups in the vicinity of the Medina River.

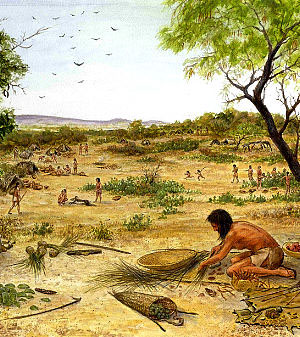

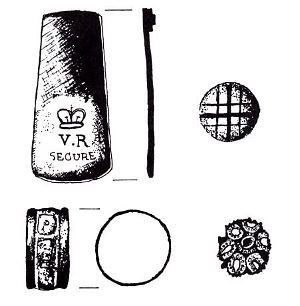

Mazanet identified six groups along the river in 1690: the Tilpayay (Payaya), the Cauya, the Semonam, the Saracuam, the Pulacuam, and the Anxau (Xauno). These groups may have shared an encampment, or rancheria, at this time. In 1691, Teran encountered a Peyaye (Payaya) rancheria in the vicinity of the San Antonio River. He commented that the Payaya were a docile and affectionate people and friendly to the Spaniards. They had erected a tall wooden cross in the midst of their rancheria. Mazanet reported that they encountered the Indians at the place known to the Indians as Yanaguana and which was named San Antonio de Padua by the Spaniards. Mazanet noted that the Payaya were a very large nation. Their settlement consisted of small clusters of shelters dispersed among a “natural open area” in a wooded locality. Both men made note of the large numbers of buffalo on the level plains near the Medina. European “trade goods” in the form of rosaries, pocket knives, cutlery, beads, and tobacco were distributed to the Indians. Some of these artifacts have been found in archeological sites in this region; native-made chipped-stone tools for meat and hide processing, such as hide scrapers and knives, also have been found in late sites in the areas.

In 1709, the Espinosa-Olivares-Aguirre expedition again encountered the Payaya on the Medina River. Southwest of its juncture with Elm Creek, members of the party carved the year 1709 into the sandstone to commemorate their expedition. Later travelers left their mark, carving other dates (1814) as well as names and brands, into the sandstone. The rock art site also contains possible prehistoric petroglyphs indicating that the spot has long been the locale for crossing the creek in both prehistoric as well as historic times. The site (41BX836) is one of few archeological sites supported by archival documentation that can be directly linked with an early entrada, the encampments of the aboriginal Native Americans, and contact between the two.

Chroniclers of the expedition noted that the Indians were not very numerous, suggesting that sometime between 1690-1709, the group may have been reduced. The expedition crossed the Medina River on April 11, 1709. In a clearing on the north bank of the river, they found a rancheria of the Payayas and later, while traveling down the river, encountered other Payayas as well as five Pampopa who were going to the rancheria of the Payayas. The party then crossed the Medina a second time (to the south bank) and arrived at the rancheria of the Pampoas (Pampopas), where they found a guide to accompany them on the next leg of the journey.

The harvesting of pecans, which were readily available along the San Antonio and Medina Rivers, seemed to be especially important to the Payaya. Pecans were important not only as a seasonal food in the fall, but as a resource that could be stored in preparation for times of scarcity. Espinosa describes the Payaya digging storage pits for the unshelled nuts. On the Medina, he recorded that one springtime encampment was occupied for at least 12 days. On their return trip from the Colorado River, eight to ten Indians of the Sijames nation were observed between the Arroyo of Leon (Leon Creek) and the Medina River. After having crossed the river on April 24, 1709, the expedition encountered the Pampopas as well as the captain of the Paxti (Pastia) nation.

Archeologists and other researchers long have studied the routes of early exploration and travel, guessing that most Spanish roads followed Indian trails that had been in use for thousands of years. In the process they have located, on rare occasions, what are termed historic “contact” sites bearing evidence left by both Europeans and native peoples. Most of these sites have been identified in the vicinity of documented Spanish colonial crossings on the Medina River. Sites identified with evidence of protohistoric use, meaning very Late Prehistoric (circa late 1400s-1500s) or the Historic Contact period in the south San Antonio area include 41BX527, 41BX528, 41BX551, 41BX836, 41BX1577, and 41BX1578. Artifacts associated with the Historic Contact period include metal knives, metal arrowpoints, glass beads (baubles), glass, copper kettle fragments, and gun parts.

A number of crossing sites with potential contact period components were identified during historical research and survey for the Applewhite Reservoir in San Antonio. Recorded crossings include the Dolores/Perez/Applewhite Crossing (41BX682); Pampopa/Paso del Talon (41BX680), one of the documented crossings utilized by Native Americans prior to Spanish use; Sabinitas/Jett/Palo Alto Crossing (41BX857); and the Paso de las Garzas (41BX697). The associated routes of exploration, trade, and commerce have also been identified through time for each of these crossings.

Archeological investigations were conducted at the Pampopa and Talon crossings (41BX528), where important roads connecting San Antonio to points along the Rio Grande River pass over the Medina. Between 1731-1737, the Pampopas fled mission confinement and were pursued to their rancherias near the “Old Ford” of the Medina River. Historic accounts tell of encampments of the Pampopa and other Indian groups nearby. The Pampopa Crossing/Ford has been positively identified at the site of 41BX527 and 41BX528 on the Medina River. The area may have served as an important point in the hide trade. As noted by archeologist Alston Thoms, the site’s setting along these travel and commerce corridors was ideal for distributing locally procured resources (eg., meat, hides and nuts) to Indian groups or to the region’s Spanish inhabitants.

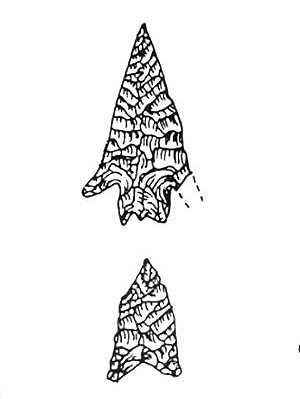

In the deposits near the surface, archeologists recorded a Cuney and Guerrero arrow point—a standard point type made by native peoples during the early Historic Period—along with perhaps earlier Perdiz points, endscrapers, aboriginal ceramics, and wheel-thrown, lead-glazed wares, suggesting the site was used during the Late Prehistoric and Historic periods. Importantly, a number of slickstones—cylindrical cobble tools with battered, polished, and scratched ends—were also found. Such tools at other sites have been associated with the bison trade, and were used primarily for rubbing and softening hides during tanning. Microscopic studies of some of the BX528 specimens showed soft-material wear such as might have resulted from rubbing gritty hides. Battering may have resulted from use as hammerstones. There were no bison bone identified at the site, however, which suggests that, although hideworking may have occurred there, butchering took place elsewhere.

With the founding of the Mission San Antonio de Valero in 1718, many of the native aboriginal groups living in the San Antonio area were relocated from their traditional habitats and concentrated into the San Antonio missions. Many of these, clearly displaced from their traditional homelands and decimated by Spanish-introduced diseases, had already lost their pre-contact cultural systems. Beginning in the mid-1700s, Spanish ranches had begun springing up along the Medina, including that of Lt. Colonel Juan Ignacio Perez and his son, Jose Ygnacio Perz, who was to become the last Spanish governor of Texas. The ranch, investigated during work on the Applewhite Reservoir, is one of the oldest in Texas.

Credits and Sources

This section was contributed by Kay E. Hindes, archeologist for the City of San Antonio. A specialist in Spanish Colonial mission archeology and archival research, Hindes was instrumental in locating the site of Mission San Saba as well as identifying a second location of Mission Espiritu Santo (41VT10) in Victoria.

Print Sources

Hatcher, Mattie Austin

1932 The Expedition of Don Domingo Teran de los Rios into Texas (1691-1692). Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society 2(1): 3-67.

Hindes, V. Kay

1995 Native American and European Contact in the Lower Medina River Valley. La Tierra 22 (2):25-31.

1992 Historic Roads and River Crossings in the Lower Medina Valley. In Historic Archaeological Investigations in the Applewhite Reservoir Project Area by Melissa Green, Randall Moir, and Kay Hindes. Archaeology Research Program, Department of Anthropology, Southern Methodist University.

McGraw, A. Joachim, John W. Clark, Jr., and Elizabeth A. Robbins (editors)

1991 A Texas Legacy: The Old San Antonio Road and the Caminos Reales, A Tricentennial History, 1691-1991. Texas State Department of Highways and Transportation.

McGraw, A. Joachim and Kay Hindes

1987 Chipped Stone and Adobe: A Cultural Resources Assessment of the Proposed Applewhite Reservoir, Bexar County, Texas. Center for Archaeological Research, the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Thoms, Alston V., and Stephen W. Ahr

1995 The Pampopa-Talon Crossings and Heerman Ranch Sites: Preliminary Results of the 1994 Southern Texas Archaeological Association Field School. La Tierra 22 (2): 34-67.

Download pdf of this article:

http://anthropology.tamu.edu/faculty/

thoms/publications/AW%20Chapter%208-Pampopa.pdf

The Spanish explorer, Domingo Teran de las Rios, found the Payaya to be

a docile and affectionate people and friendly to the Spaniards. |

|