|

One of the small Indian nations occupying the Trans-Pecos has long intrigued archeologists and ethnohistorians: the Jumano. The Jumano were a distinct nation, mentioned by name in a precious few Spanish documents beginning in 1583 and continuing until around 1750. The written record shows that they were mobile hunter-gatherers who frequently moved and often traveled great distances. Along the way they interacted with many different friends and enemies. Their movements and dynamic relationships reflect extraordinary efforts to persist as a unique group despite the horrific consequences of the Spanish colonization. In the 18th century the surviving Jumano seem to have joined forces with one of their formerly bitter enemies, the Apache, and soon faded from history as a named people like so many other native peoples.

Scholarly Debate

Professional archeologists, historians, and ethnohistorians have long taken great interest in the Jumano—who were they, who were they not, where did they live, who were their allies, etc. Other Indian nations are mentioned more frequently in the Spanish documents (such as the Tigua, Manso, and Suma who lived in the El Paso area) and those documents provide many richer details of those groups. Yet, the Jumano have piqued the greater interest of researchers. This interest is attributed to several factors. Several times the Jumano appealed to Spanish officials and priests to come to their homelands and build presidios and missions, indicating they lived in a region rich in water, nuts, buffalo, and even had fresh-water clams with pearls—things that attracted Spanish interest and created some speculative comments in documents. These types of speculative comments often pique modern scholars. But another, and perhaps more compelling reason the Jumano have been of such interest is their presence in far-flung campsites visited by Spanish soldiers and priests. These campsites stretched from New Mexico to El Paso to camps along what is now the I-35 corridor east of the Balcones Escarpment. Scholars have tried to account for the vast distances traveled by the Jumano and the reasons behind it.

This scholarly interest has led researchers in several different directions. This is not unusual. Scholars in all fields disagree almost as often as they agree. Sometimes scholars disagree because one or another uses incomplete information. Scholars working in the late 19th or early 20th century did not have access to the volume of Spanish documents that have come to light in the last 50 years. As new information is found and presented, ideas and interpretations change in much the same way as do engineering, medicine, business, and many other fields over the last century.

Scholars also interpret the evidence differently. For example, some scholars today say that the name Jumano is an overarching name that included many other nations such as the Cholomes, Cibolos, Patarabueyes, and others. Others using the same documentary evidence claim that the Jumano were the people who occupied a group of pueblos in eastern New Mexico that the Spanish called the “Humanas pueblos” in 1598. Still others envision the Jumano as a group of quintessential traders that traveled over long distances from La Junta at Presidio, Texas to the salt lakes near the Humanas pueblos, the Southern Plains, the Red River in the region of the Rolling Plains, West Central Texas (vicinity of the Colorado and Concho rivers), East Texas near the Hasinai Caddo, and the Texas Gulf Coast near Victoria, hawking their wares to all and sundry.

Here, we follow author Nancy Kenmotsu’s research and interpretations which have been advanced in her 1994 dissertation and a 2001 article and many scholarly presentations. Thus, we regard the Jumano as a distinct nation, a people who originally resided in the eastern edge of the Trans-Pecos and the adjacent northwestern portions of the Plateaus and Canyonlands region. During the two centuries that the Jumano are known from written accounts, they are noted as having a changing set of friends and enemies—dynamic social relations that reflect their efforts to cope with the changes brought by Spanish colonization of Nueva Vizcaya to the south of them, New Mexico to the west of them, and later central and east Texas to the east of them.

Who were the Jumanos and Where Did They Live?

Let’s begin to understand the Jumano by looking at their homelands. The first recorded visit to their homelands was in 1583 when the Espejo expedition to New Mexico returned to Mexico. These men were the first Europeans to travel down the Pecos River, beginning at what is today Pecos National Monument in New Mexico. The documents of their journey alternately called the Pecos the Rio de las Vacas (River of the Cows, meaning buffalo) and Rio Salado (Salty River). For almost 260 miles, the Spaniards saw no Indians or buffalo. In fact, the men encountered little game to eat, something that “greatly troubled” them. In other words, they expected to find buffalo to eat; instead they only saw buffalo bones and the bones of other animals.

Finally, in the vicinity of the Toyah Creek confluence with the Pecos, three Jumanos came across the expedition and led the hungry Spanish to their camps. The Jumano cordially greeted the Spanish and shared with them catfish, “sardines” and other fish, roasted and raw calabashes (gourds), and prickly pears. Not surprisingly, the diary of Diego Perez de Lujan, the official diarist for the expedition, said, “the food was delicious.” As they traveled through the Jumano camps, most evenings were filled with music and dancing. A good time was had by all.

These brief descriptions indicate the Jumano in the 1580s were a contented people. Certainly, they showed no fear of the newcomers. The lack of fear is telling. Even before the 1580s, Indians living north of the Spanish settlements, ranches, and mines were being captured by clandestine Spanish slavers and hauled hundreds of miles to the south where they were forced to do heavy manual labor. Many of the residents of Indian villages visited by the Espejo expedition on their way to New Mexico in 1582 had exhibited fear and reluctance until convinced that these Spaniards had not come to capture slaves. In contrast, the Jumano welcomed the men into their camps and even guided the expedition back a place that they knew well, La Junta de los Rios, “the joining of the rivers” where the Rio Conchos of Mexico flows into the Rio Grande in the vicinity of Presidio, Texas (see La Junta exhibit). While their lack of fearfulness may reflect their distance from the Spanish towns, ranches, and mines in northern Mexico, other documentary data suggest that the Jumanos were able and willing to defend themselves. For example, a few years later, in 1599, the Apache on the Southern Plains requested Spanish aid against the Jumano.

From the Espejo expedition’s diary, we learn that dispersed Jumano camps were located along the Pecos and its tributaries, and adjacent to active springs at the bases of mountains. We don’t know how far up or down the Pecos they camped or which mountains these were, but they may have been the Delaware or Apache mountains to the west or along the escarpment near Sheffield, Texas to the east of the Pecos River.

While these lands are those the Jumano occupied in the late sixteenth century, it is clear that they had intimate knowledge of a much broader landscape. Most of the Trans-Pecos must have been familiar to them. When they met the three Jumano in 1583, the Spaniards, through an Indian interpreter who spoke the Jumano language, happily told the Jumano that they were going to follow the Pecos to the Rio Bravo del Norte (the Rio Grande) and from there to the Spanish settlements to the south. They falsely believed the confluence of the Pecos with the Rio Grande was at La Junta, when in fact the Pecos joins the Rio Grande some 200 miles farther downstream near Langtry, Texas. The Jumano knew perfectly well that the planned route would not lead to the Spanish settlements and told the Spaniards so, offering to guide them along “good roads” (established trails) to the proper La Junta.

In addition to this easy familiarity with a land stretching from today’s Del Rio to Presidio and north to Pecos, Texas, the Jumano also traveled north with frequency to the Humanas pueblos in New Mexico. Benevides, a priest familiar with the Humanas pueblos, wrote in 1634 that the pueblos were called “Xumanas because this nation [the Jumano] often comes to it to barter and trade.” How many of us today could boast such intimacy with such a broad region, especially a region one would only travel on foot?

Over the next century, the documents give us better glimpses into the homelands of the Jumano. One of the more dramatic is in a sweeping memorial (an official report) written by Father Benavides in 1629 discussing the Native Americans important to New Mexico at that time. In the report, he writes of the “miraculous conversion of the Xumana nation,” meaning their conversion to Christianity and Catholicism. He states that this nation lived “112 leagues” from the Humanas pueblos and notes that the Jumano lands “border” on the land of the Humanas pueblos, and describes the Jumano homeland as east of the Apache. The conversion described by Benavides was undertaken in 1629 by Fray Juan de Salas who journeyed to the Jumanos after their repeated requests for a mission in their homeland. These requests were made in regular visits they made to their friends in the Humanas pueblos. In 1632, Salas again visited their camps, leaving a priest among them for six months. Like all summaries, the report needs to be taken with a grain of salt. Benavides was the official Franciscan custodian of the Catholic churches of New Mexico from 1623 to 1629, but did not arrive in New Mexico until 1625 leaving him with only a few short years to learn of the many nations detailed in his report. In this case, however, the repeated contact between Salas and the Jumano as well as Benavides' treks to see them appear to provide reasonably accurate information on their homelands. This begins to show that their homeland was not confined to the Pecos but rather stretched east from it.

In 1650 more information becomes available when soldiers, led by Captain Diego del Castillo, traveled 200 leagues southeast of Santa Fe and spent six months in the Jumano homeland on what they call the rio de las Nueces (River of the nuts). While the type of nut is not stated, we assume that it was a nut of interest to the soldiers, and strongly suspect that the nuts referred to are pecans, which commonly grew along the major rivers found east of the Trans-Pecos. Documents that discuss this journey also speak of the discovery of pearls in the rivers where the Jumano camps were located. Fresh-water pearls are known from the Concho River in the vicinity of San Angelo (see River of Pearl).

Documents from the 1680s provide still more information about the Jumano homelands. They demonstrate that the Jumano homelands stretch from the Pecos to the San Angelo region, but no longer include the southern part of the Southern Plains in eastern New Mexico—much to the frustration of the Jumano. They also demonstrate the fierce attachment that the Jumano had to their homelands and that they would go to great length to keep those lands from their enemies, the Apaches. The accounts also underscore how a creative agent—the Jumano cacique (leader) by the name of Juan Sabeata—attempted to help his people and his homelands. Keep in mind that this was just three short years after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in Santa Fe. The Spanish who survived that revolt fled to El Paso for their lives, and even in 1683, they were reeling. In 1681, Governor Otermin had written to his superiors in Mexico City begging for help, stating that he had more than 2,000 souls (Indian and Spanish) to feed, but the few cows he had to slaughter were insufficient for all and a drought had emptied his coffers of corn.

Enter Juan Sabeata who had traveled up the Rio Grande to El Paso from La Junta, where friends of the Jumano resided. Accompanied by a contingent of 11 other Jumano leaders, Sabeata pleaded with the Spanish to establish missions and presidios in his homelands. Each of the 12 “were captains of different Jumano camps.” He assured Governor Otermin that he and the Jumano friends in New Mexico (likely the people in the Humanas pueblos) had been loyal to the Spanish over the years. He also assured the governor that the Jumano were at war with the Apache. While documentary evidence confirms that this was a true statement, Sabeata was well aware that the Spanish felt dangerously threatened by those same Apache. These and other recorded statements show that Sabeata negotiated for his people by appealing to notions (action against the dreaded Apache, new lands, thousands of souls to baptize, etc.) that he knew the Spanish would favor.

Eventually, the Spanish authorities agreed to send an expedition to the Jumano homeland just as Sabeata had requested. An excellent account of the 1683-1684 Mendoza-Lopez expedition is in Maria Wade’s 2002 study, The Native Americans of the Texas Edwards Plateau 1582-1799. Using several versions of the diaries and other accounts of the journey, she chronicles their travels from El Paso to La Junta to the Concho River of Texas near San Angelo.

Later, in 1688 when General Retana traveled four days northeast of La Junta to meet with the Indians that were to bring him word of the French on the Gulf Coast, he was greeted by Juan Sabeata who said he “was very glad to see the Spanish in his lands” indicating that this region was the one where the Jumano lived. Four days travel northeast of La Junta would place the meeting in the vicinity of the Pecos River. To solidify this location, when the Jumano were encountered along the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau in 1691, they stated that their homeland was the “Rio Salado” or Pecos River. In sum, at least as late as 1691 the Jumano maintained their homeland between the Pecos and Concho rivers of Texas.

Jumano and the Humanas Pueblos

The Jumano were not an isolated people. They had friends and, during the period we know them, they kept old friends while cultivating new ones. Like us today, their friends were people they enjoyed spending time with and, as friends, they supported each other during good times and bad. In fact, we believe that the Jumano presence in far-flung places represents their concerted efforts to both cultivate new friends and maintain old friendships.

During their early appearance in the written record, the Jumano’s closest alliance was with people in the Humanas pueblos. As noted above, the pueblos were called the Humanas pueblos because the Jumano often visited them and because some (or all) of the residents of the pueblos were said (as early as 1601) to have stripes on their noses. It is not clear from the documents whether their markings were permanent or painted. Nonetheless, the face marking is important. There is no evidence to suggest that other puebloan people marked their faces even though they interacted with the people in the Humanas pueblos. The Humanas people, then, stood out in a crowd. Yet, people simply do not quickly adopt a mannerism that will distinguish them from others, particularly if the mannerism is that of a group that they do not like and that they do not need to adopt.

Clearly there was no need for the people of the Humanas pueblos to stripe their noses, given the fact that other puebloans did not, hence marked faces suggests one or more of the following social mechanisms at work: (1) they simply admired this physical adornment of their friends and adopted it, ignoring broader social custom; (2) they intermarried with the Jumano, and since their marriage partners from the Jumano were permanently tattooed, they followed suit; (3) they sought to put their friends at ease; or, (4) the people of the Humanas pueblos wanted other pueblos and other Plains groups to recognize that they had a close relationship with the Jumano. The latter is not unusual. Ample archeological and documentary evidence exist to show that the residents of Pecos pueblo had a similarly close alliance with the Apache. Later in time, the Comanche developed a reciprocal relationship with Taos Pueblo.

Such relationships were mutually beneficial. Each partner could provide different goods. Some goods were tangible: meat and hides for salt, corn, and other domesticated crops, and marriage partners. Another prime “item” of exchange cannot be directly found in the archeological or documentary records: information. For example, people in the pueblos would want to know about possible dangerous enemies to the east of them; the Jumano with their mobile life style could provide such information. They could also bring news of events (droughts, floods, battles, etc.) that had taken place at great distances. At the same time, if the Jumano were feared as mobile warriors, a friendship with them, particularly one that was visibly announced to the world via nose tattoos, could make the residents of the Humanas pueblos safer from their enemies.

Eventually the Jumano turned to other friends because the three Humanas pueblos did not survive past 1672. Although documents from 1661 described the pueblos as "the most populous [pueblos]...in those provinces" with over 3,000 souls, Spanish priests and governmental officials in New Mexico were increasingly at odds with each other from as early as 1630, and some of the priests actively involved in the debate were those serving the Humanas pueblos. Each side made charges against the other. Priests warned natives against performing their traditional dances (catzinas) believing that they were a form of pagan idolatry. Priests charged that governmental officials told natives to ignore the priests. They also charged that government and civilian officials were enslaving the people of the pueblos as well as other Indians who came to their pueblos to trade and barter. Residents of the pueblos and other nearby settlements were forced to extract salt from the nearby salt lakes and haul it all the way to Parral and other places. At the same time, priests expected the Indians to build the churches and other structures that they required.

Another population stress occurred during times when the region was recovering from a horrific drought, maturing crops could not be fully harvested because of the lack of people to do the work. In the years, 1666 to 1669, another drought gripped the region and for three years no crops were grown. In the Humanas pueblo today known as Gran Quivira, more than 450 people died of starvation. At the close of the drought, Apache attacks on the Humanas pueblos stepped up. September 3, 1670, the Apache of the Seven Rivers attacked the pueblo and sorely damaged the church and pueblo. Eleven people died in the attack and another 30 were taken prisoners.

As if these difficulties were not enough injury to the pueblos, archeological excavations at the Humanas pueblo indicates that at about this same time missionaries destroyed their kivas, the communal religious rooms the Spanish regarded as pagan structures. When the Spanish destroyed these kivas, they likely considered the act a means of crushing old, inappropriate, non-western religious values. No doubt the Indians held a quite different view. The result of the combined woes was predictable: by 1672, the Humanas pueblos were largely abandoned, and these friends of the Jumano were scattered.

Jumano and the La Juntans

Not surprisingly, the Jumano had other friends in other places bordering on their homelands. One of them was the Patarabuey villagers of La Junta. When the Jumano efficiently guided the Espejo expedition back to La Junta in 1583 they followed a path they knew well, indicating a long-standing, friendly alliance with the people who lived there. Yet, in contrast to their close alliance with the Humanas pueblos, documentary data indicate that this friendship was different. The Jumano were received in La Junta with warmth, but politely. Goods were exchanged but the documents do not express the conviviality the Spanish experienced in the Jumano rancherias along the Pecos River. This may simply reflect that the Spaniards were anxious to return to their settlements to the south and too preoccupied to mention how the groups interacted. Yet, subsequent documents suggest that the Jumano were not as close to the people in La Junta as they had been to the people in the Humanas pueblos. Scores of documents from the Archivo del Hidalgo del Parral [Archive of the Township of Parral], written between 1632 and 1682, contain data related to the people living in La Junta and the names of the Indian nations that visited them; none mention the Jumano. If the Jumano were close friends, at least some documents should mention their visits to La Junta. Since none do, it appears that the Jumano relationship with the Patarabuey during this early period was more distant, with infrequent visits to maintain sporadic contact.

To some extent, this relationship must have been altered by the outcome of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Earlier we noted that the Spanish were stunned by the revolt and fled to El Paso to regroup. While there, Juan Sabeata and the 11 other Jumano leaders visited to ask the Spanish to visit their lands to the east. Sabeata deliberately used La Junta as his staging area, something that he could not have done unless he had the agreement of the people of La Junta. When the governor of El Paso explained his pending retirement and advised Sabeata to return in three months to speak to his replacement, Sabeata agrees and returns to his friends at La Junta to await the arrival of the new governor. When that governor arrived, Sabeata returned to El Paso to plead his case in October of 1683. As part of his case, he stated that the people of La Junta desired priests and baptism. These events show that the relationship of the Jumano with the people of La Junta continued to be positive and had probably grown stronger since the mid-17th century. Evidence exists that the relationship continued at least as late as 1687 when Jumano were among the Indians who, at the request of the Spanish, brought to La Junta news of the French along the Texas Gulf Coast. After 1687, the Jumano name again disappears from among the nations visiting at La Junta. |

The Jumano Problem

The Spanish also spelled their name as: Humano, Xumana, Jumana, Jumanes, Xoman, or Xumano. The French documents called them Chomano and Chumano. It is not uncommon to find Indian names spelled differently in different documents or even differently in the same document. The Spanish and French scribes simply tried to phonetically write group names down. Each heard the name slightly differently, and this led to variant spellings, as is the case for most groups mentioned repeatedly in the archival record.

The Jumano’s name was not only spelled differently at times, the Spanish also used it for several distinct and unrelated groups. It was first used as the name of a group of Indians living along the Pecos River in the eastern Trans-Pecos in 1583. Those documents describe them as hunters and gatherers, subsisting on bison and “the meals that the land will give them [because] they do not sow”.

In contrast to those descriptions, three pueblos, located in east-central New Mexico near several large salt lakes, were called “Humanas pueblos” in 1598. Today, the archeological remains of these pueblos make up Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument. Excavations there (and documentary accounts) have shown that these pueblos were occupied by large populations who grew corn and other domesticated crops. The pueblos were on the eastern fringe of Spanish New Mexico and the Spanish gave them limited attention. As a result, the documents related to the Humanas pueblos and their occupants are not very detailed.

Still other Indian groups, spread from Arizona to north Texas, were at different times also said to be “Jumanos.” These documentary inconsistencies made reconciliation of the Jumanos as hunters and gatherers, sedentary puebloans, or both, quite problematic to scholars.

This “Jumano problem” as it came to be known was clarified in 1940 by a historian (Frances V. Scholes) and an archeologist (H. P. Mera) working together. Using archival and archeological data, they convincingly argued that the word Jumano had two different meanings: it referred to people who painted or tattooed their bodies (rayado in Spanish), and it was also used as the name of a particular nation that occupied lands along the Pecos River of Texas. People known as the Jumano as well as people in all of the other places where the documents call the Indians Jumano either painted or tattooed their faces or bodies. |

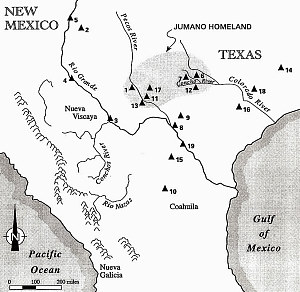

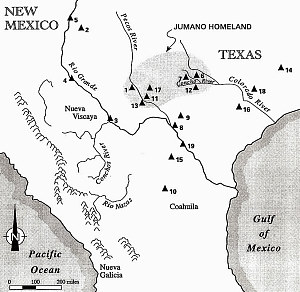

Map showing the original Jumano homeland as known from early Spanish encounters as well as locations where they were encountered then and later. (See below list). From Kenmotsu 2001.  |

Spanish - Jumano Encounters

1580 - 1750

1. Pecos River , 1583

2. Humanas Pueblos

3. La Junta de los Rios, 1583-1688

4. El Paso, 1683-1788

5. Ysleta

6. Concho River, 1629

7. Concho River, 1654

8. Sacatsol, 1674

9. Dacate, 1675

10. Rio Sabinas ,1689, 1691

11. Pecos River, 1683

12. Rio Concho, 1683

13. Rio Salado (Pecos River), 1689

14. Tejas Villages (Caddo), 1688

15. Rio Sabinas, 1690

16. Guadalupe River, 1691

17. north of La Junta, 1693

18. north of Colorado River, 1691

19. Mission San Bernardo, 1706

20. Apaches Jumanes, northwest of San Antonio, 1716 (not shown)

|

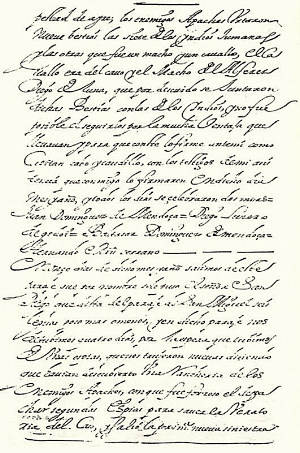

Page from diarist of Juan Dominguez de Mendoza’s expedition in 1684. |

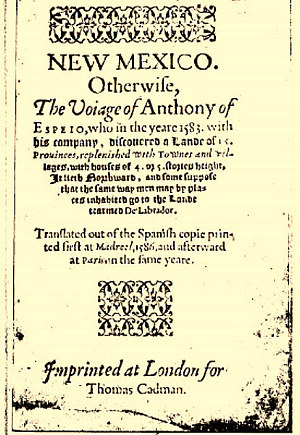

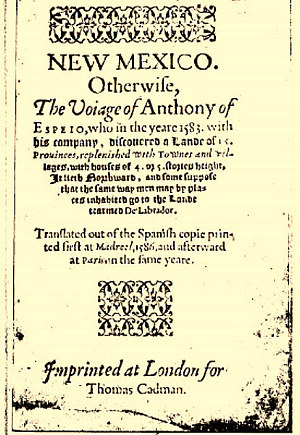

Cover of the published version of the journal of Diego Pérez de Luxán who chronicled the 1582-1583 Espejo expedition. The group traveled down the Río Conchos, explored the La Junta area, then went up the Rio Grande to New Mexico. The return trip was by way of the Pecos River to the vicinity of Toyah Creek (north-central Reeves County), where they were guided by Jumanos back to La Junta.  |

A herd of grazing bison. The Jumano were known as bison hunters and their homeland in the northeastern Trans-Pecos and northwestern Plateaus and Canyonlands was bison country. Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife.  |

Ruins of Quarai Pueblo, one of the Humanas pueblos in eastern New Mexico that are today part of the Salinas Pueblos Missions National Monument. Photo courtesy Walter Brisken.  |

Toyah Lake is a broad playa fed by intermittent rainfall and Toyah Creek that lies within the Jumano homeland. Although typically dry or only shallowly filled with water, the playa would have served as a watering hole for buffalo in the past and as a stop for migratory birds and other creatures in more recent times. It is likely that Jumano groups visited Toyah Lake on bison hunts. Photo by Susan Dial.  |

This Jumano man, as depicted by artist Frank Weir, wears a deerskin robe.  |

|