| The companion exhibit, Hank's House 1: Anatomy of a Burned Pithouse, tells all about how the house was found and investigated, what it contained, what it looked like, when it was built and burned, and so on. In Hank's House 2 we turn to the bigger picture and the problem of trying to fit Hank's house into what is known about the Plains villagers of the Texas Panhandle. The story that follows—A Puzzle Wrapped in a Mystery—gives insight into the thought processes of the archeologists as they worked to unravel the story of Hank's house. It also shows how perceptions can change as new and important data come to light. This exhibit departs from the usual Texas Beyond History format. It is an interpretive essay that relies more on words and ideas than images and we've chosen to keep it together as a narrative. Author John R. Erickson is the rancher and professional writer who found the site on the M-Cross Ranch that he and wife Kris Erickson own in Roberts County. Doug Boyd, the archeologist who directed the work at Hank's site has this to say about Erickson:

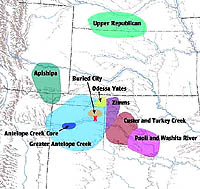

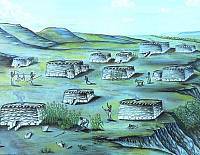

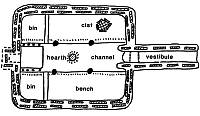

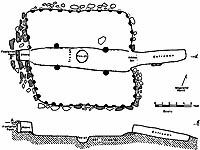

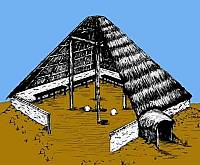

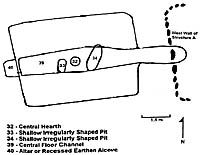

As you read the below story, perhaps you will think about things that you have never thought about before. Please remember that the archeological investigation of Hank's site is a story unfolding. Most archeological endeavors are, in fact, a series of ongoing learning processes for which there is no real end. Perhaps the most important thing that can be gained from years of studying Panhandle archeology and prehistory is a great appreciation for its many complexities. No matter how long you have studied, and how much you know, most Panhandle archeologists eventually come to realize that we are all merely greenhorns and have much to learn about the cultures who called this place home. A Puzzle Wrapped in a MysteryTo appreciate the significance of Hank's house, we begin with a brief review of Southern Plains archeology in general, as our archeological team understood it at the time the excavation began in November of 2000. This is important because, as we will see, Hank's house exposed some gaps in the overall picture of archeology in the Texas Panhandle. To understand who might who might have lived at Hank's house, we must look at three variables simultaneously: time, space, and culture. Between about A.D. 1200 and 1450, the Canadian River Valley of the Texas Panhandle and western Oklahoma was inhabited by several groups of Plains Village peoples. The Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles were home to the Antelope Creek culture, and their core area was centered around the section of the Canadian River that is now Lake Meredith. In the northeastern corner of the Texas Panhandle and covering large portions of Ochiltree and Lipscomb counties, Buried City peoples lived along Wolf Creek, a tributary to the Canadian River. A little further to the west, in the northwestern corner of Oklahoma, archeologists recognize the Zimms complex. Just south of that, the Turkey Creek phase (formerly the western section of the Washita River phase). Beyond this, scholars recognize many other similar cultural manifestations in adjacent states, but only two are mentioned here because they come into our story later. To the northwest is the Apishapa phase (southeastern Colorado) and farther to the north is the Upper Republican phase (Kansas and Nebraska). Each of these names, which are usually called "phases" or "complexes" by archeologists, is thought to represent a distinct "culture" or group of people. They all share many traits in common, but are distinguished by differences in material culture, architecture, burial practices, and even skeletal characteristics. All of the groups mentioned above had common traits that identified them as Southern Plains Villagers and distinguish them from the Plains Woodland cultures that preceded them. They made pottery and hunted bison with arrows tipped with side-notched points. They relied to some extent on the gathering of wild plants, but also cultivated corn and other crops in garden plots. And, most important, they had evolved from the pattern of nomadic hunting and gathering followed by their early ancestors and lived in small hamlets and villages—thus the name "Plains Villagers." The appearance of villages on the Southern Plains introduced a new diagnostic element into Southern Plains archeology: architecture. Where earlier cultural groups, the Archaic and Woodland peoples, had sheltered themselves in ledge caves and temporary pithouse dwellings that archeologist have difficultly finding, the Plains Villagers built more substantial houses, the ruins of which have, in many cases, survived into the twentieth century to be excavated and studied by archeologists (and dug into more haphazardly by treasure seekers). These houses came in different sizes and shapes: small, large, circular, square, and rectangular; some were single-room structures, while others contained multiple rooms. Hence, the analysis of house design and structure is an important component in the overall interpretation of the various Southern Plains Village cultures, offering some clues as to how one group might or might not be related to another. Architecture is one of the things that remains most distinctive of cultures all around the world today, and the history of architecture is an exciting field of study. It is not at all surprising that modern historical architects trace specific architectural traits through time and across space in order to understand movements of different groups and the influences they have had on others. This same concept applies to the archeological remains of buildings and structures, including those in the Texas Panhandle. Although the Southern Plains Village groups shared some common traits in their house architecture, the prehistoric structures in the Texas Panhandle had two features that made them unique. First, most of the houses contained walls and foundations made of stone-vertical slabs in the Antelope Creek culture houses near Amarillo, Texas, and round caliche rocks in the Buried City complex southeast of Perryton, Texas. And second, all rectangular prehistoric structures in the Panhandle had a central channel running through the middle of the house, with raised "benches" on either side and, usually, a raised "altar" at the rear. At the time we began the excavation on Hank's house, Plains Village archeology in the Panhandle usually meant Antelope Creek, whose extensive stone-slab ruins along the Canadian River south of Amarillo had fascinated archeologists for almost a century. With such a wealth of sites with shallowly buried houses easily identified by the structural rocks poking above the surface (and, coincidentally, very vulnerable to destruction by pot hunters and oil field construction), it is hardly surprising that archeologists concentrated their excavations on the stone ruins that occurred in a four-county (Moore, Potter, Hutchinson, and Oldham) area around the Alibates flint quarries, the heart of the Antelope Creek manifestation. Studies of Antelope Creek sites proliferated, authored by Ele and Jewel Baker, T.C. Holden, Floyd Studer, Lathel Duffield, Alex Krieger, F. Earl Green, David Baerreis, Reid Bryson, Billy Harrison, Jack T. Hughes, and others, and culminated in the publication in 1986 of Christopher Lintz's monumental study Architecture and Community Variability Within the Antelope Creek Phase of the Texas Panhandle. Work had also been done on the smaller cluster of ruins at Buried City in the northeastern Panhandle, and this was the location of one of the earliest scientific excavations in Texas. In 1906, Professor T. L. Eyerly and his students from the Canadian Academy, of Canadian, Texas, became the first of many to dig there. But the work at Buried City didn't compare in volume to the research devoted to Antelope Creek sites. Even as late as the 1990s, when archeologists made cultural maps of the Panhandle, they showed the circle of Antelope Creek occupation covering the entire Panhandle, from New Mexico on the west to Oklahoma on the east, while the Buried City complex occupied a small balloon within the larger circle. Buried City was recognized as representing something different, but exactly what that was wasn't clear. Hank's site is located on a ranch in Roberts County, fifty or sixty miles east of the heaviest concentration of Antelope Creek village sites, but well within the circle of suspected Antelope Creek occupation. Everything we knew about Panhandle archeology convinced us that Hank's house would reveal ties to Antelope Creek sites up the river. Since our first radiocarbon date suggested an occupation around 1100 A.D., and since the structure we uncovered was of picket-post wall construction, not the stone-slab architecture of Antelope Creek, our working hypothesis at this point suggested that: 1) the occupants of Hank's house were ancestors of the Antelope Creek people; and 2) picket-post construction was an early manifestation of building that later evolved into the stone-slab architecture of Antelope Creek. The Origins of Antelope CreekThis drew us into the realm of the Great Unanswered Question in Texas Panhandle archeology: Where did the Antelope Creek people come from? Or, to put it another way, how and why did they end up in the valley of the Canadian River sometime between 1200 and 1250 A.D. with a fully developed Plains Village culture-hunting bison, growing corn, and building substantial stone houses and villages? Archeologists have puzzled about this for nearly a century, at least since Professor Eyerly excavated at the Buried City in 1906. When Warren K. Moorehead made his trek across the Panhandle in 1920, he recorded more than a hundred stone-ruin sites. Moorehead and other investigators believed that the distinctive stone masonry in the Panhandle pointed to a strong influence from the Pueblos of the Southwest, and for years the ruins were attributed to a group of people called the Pueblo Culture of the Texas Panhandle. But once archeological excavations began in earnest, investigators found more evidence of links to Plains Village groups than to the Pueblos. The debate about Antelope Creek origins has centered on two questions: Did they evolve out of local Woodland groups? Or, did Plains Village people migrate into the Panhandle from other areas? In 1962 Jack Hughes published the results of an investigation he did at the Lake Creek site in Hutchinson County. The Lake Creek site, he argued, provided evidence of a Woodland group that was present in the Canadian River valley before the appearance of Antelope Creek. Antelope Creek people, he said latter in a 1991 article, were rooted in Lake Creek and evolved out of an indigenous Plains Woodland horizon, "with cultural infusions from Mogollon, Anasazi, and Upper Republican sources." Robert Campbell, a scholar who did his doctoral research on the Chaquaqua Plateau of southeastern Colorado, proposed a different scenario in his 1976 book, The Panhandle Aspect of the Chaquaqua Plateau. Campbell argued that around 1200 A.D., a Plains Village group called Apishapa came under the spell of a prolonged drought and migrated south and east into the Canadian River valley, bringing with them their knowledge of stone masonry. In the Texas Panhandle, they came in contact with local Woodland groups (Hughes's Lake Creek folks) who had learned rectangular house-building techniques from Custer or Washita River people from the east. Out of this mingling of cultures and ideas, Campbell argued, came Antelope Creek, and its "Type I" rectangular houses with walls and foundations made of stone. (Type I is the designation Christopher Lintz gave to the most common house style in Antelope Creek sites). Campbell's model of Antelope Creek origins was elegant in its simplicity and intuitively satisfying. Where did the stone masonry come from? The Apishapa. Why did the Apishapa move into the Panhandle? Drought. Where did the Type I rectangular house come from? The Washita River people. Why did they come into the Panhandle? They had hunted and foraged there for years, maybe centuries, and some of them decided to stay. When the Type I house with post walls met Apishapa stone masons in the central Panhandle, the classic Type I rectangular houses with slab foundations appeared. But two years after the publication of Campbell's book, his migration theory drew a withering critique from a very formidable opponent, Christopher Lintz. In a 1978 paper called "Architecture and Radiocarbon Dating of the Antelope Creek Focus: A Test of Campbell's Model," Lintz attacked the Campbell model, arguing that a thorough analysis of Antelope Creek radiocarbon dates did not support Campbell's migration theory. He stated: "Although this model fits well with the phylogenic relationship proposed between Apishapa and Antelope Creek foci, the chronological evidence supporting the architectural changes in Antelope Creek has been selectively represented. Far more chronological information could have been used to develop the model." Although some observers have wondered about the reliability of those carbon dates, many of which were made decades ago when the science of carbon dating was in its infancy, Lintz's critique cast a dark shadow over the Campbell model, and today one seldom hears about it. How, then, did Lintz explain the appearance and development of Antelope Creek focus in the Panhandle? In his 1984 PhD dissertation (published in 1986) he refuted theories that Antelope Creek derived from migrations of Upper Republican, "Southwestern groups," "late Gibson aspect Caddoans to the east," the Apishapa to the northwest, Custer-Washita groups, or various combinations of these. Instead, he chose Jack Hughes's hypothesis that Antelope Creek "may have developed gradually out of Woodland under Basketmaker influences to the west and Hopwellian and Gibson influences to the east." Lintz called this: A persuasive argument based on (Hughes's) extensive familiarity with the Texas panhandle archeology. ...The Lake Creek complex, an indigenous Plains Woodland adaptation in the Texas Panhandle, is regarded as a likely antecedent of the Antelope Creek phase…Antelope Creek thus reflects the introduction of new architectural ideas around the same time that the local Woodland group was being transformed into a Plains Village complex. Picket-Post ArchitectureLintz and Hughes, two of the most respected authorities on Panhandle archeology, had come down on the side of an Indigenous Development hypothesis: Antelope Creek grew out of Woodland roots. But our team at Hank's site was having a problem fitting our 1100 A.D. picket-post structure into this scenario. It bothered us that, more than forty years after Hughes had proposed his Lake Creek complex, nobody had found any kind of structures in Lake Creek sites. No one had found any firm evidence that explained how Woodland people made the huge leap, presumably from simple pithouses (basically holes in the ground covered with branches and animal skins) to the elaborate architecture found in Antelope Creek villages. At the time Hughes wrote his article on Lake Creek (1962), he believed that the evidence would turn up in subsequent excavations, but that has not happened. Even though Robert Campbell's migration model had been discredited and largely forgotten, we felt that it offered a plausible answer to our biggest question - what was an 1100 A.D. picket-post house doing in Roberts County, halfway between Antelope Creek and Washita River habitation sites? Campbell's answer, which our team dubbed the Oklahoma hypothesis, argued that Custer-Washita River groups migrated westward up the Washita and Canadian Rivers, established outposts in the Texas Panhandle, merged with Apishapa stone masons, and blended into the complex that became Antelope Creek. What we uncovered at Hank's site was almost an exact copy of the Type I structure Lintz had documented at many Antelope Creek locations: rectangular, four interior support posts, central hearth, an east-facing entryway, and a central channel flanked by benches. The similarities were striking, but so were the differences. Hank's house had no raised "altar" opposite the entryway, but this feature is not always present in Type I Antelope Creek houses. More important, there wasn't a single rock in the foundation or walls of Hank's house. Stone-slab masonry was the most conspicuous diagnostic element in Antelope Creek architecture, yet the walls of our house had been constructed of vertical picket posts, similar to what archeologists would call "wattle and daub." In wattle and daub architecture, vertical posts are set into the ground and horizontal branches are lashed to them to form a lattice framework. Grass or thatch is woven throughout the lattice frame, and wet clay is applied to the interior and exterior. When it dries, the clay binds and forms an adobe-like wall that is very strong because it is bonded to strong wooden posts. A true wattle and daub house is an above-ground structure, while Hank's house was a semi-subterranean earth lodge-like a half dugout with an earthen roof-that had picket-post walls. Picket-post construction was rare in the Panhandle. Some forty miles to the west of Hank's house, Billy Harrison and the West Texas State University Anthropological Society had excavated a picket-post house at the Jack Allen site. Another picket-post structure had been documented at a site called Footprint, in the heart of the Antelope Creek occupation zone. These two structures had been known to archeologists for decades, but had always been regarded as anomalies-variants of the standard stone-slab architectural of Antelope Creek. (Note to readers: when archeologists find things that don't fit their models, they call them anomalies or variants!) But we had found another picket-post house at Hank's Site. Could they all be "variants?" Architecturally, the Jack Allen house is a dead ringer for Hank's house, and it is noteworthy that Billy Harrison recognized that the lack of wall rocks was so unusual. In an unpublished manuscript written in 1983, Harrison stated that, "This house and others like it may form a new style of architecture for the Antelope Creek focus." The research team embarked on an extensive literature-search on the subject of picket-post architecture. We searched the literature from adjoining states, especially Oklahoma. Poring over the research of Richard Drass, Peggy Flynn, Robert Bell, Robert Brooks, Jack Hofman, Don Wycoff, and other Oklahoma scholars, we found numerous references to picket-post houses that began at the hundredth meridian (the Texas-Oklahoma state line) and extended all the way into the heart of the state, most of them located on the Washita River and its tributaries. Some of the houses from Custer (southwestern Oklahoma) and Paoli (south-central Oklahoma) phase sites were old enough to be transitional-Woodland structures, while others, from the Turkey Creek (southwestern Oklahoma) and Washita River (south-central Oklahoma) phases, and the Zimms complex (northwestern Oklahoma), appeared to be contemporaneous with Antelope Creek sites. In many cases, the similarities to Hank's house were striking. Type I picket-post structures at Currie 4, Patton A, Goodman I, Heerwald, Zimms 2, and Hedding began to suggest a cultural affiliation between Hank's house and the well-developed Plains Village cultures in western and central Oklahoma. A search of Upper Republican literature showed more of the same. Although the Upper Republican houses in Kansas and Nebraska are generally considered to "earth lodges" of various forms and sizes, many of these houses were essentially Type I picket-post structures very similar to Hank's house but generally larger. Our next objective was to take a closer look at excavations and survey work that had been done in our own back yard, the eastern Texas Panhandle, but which had never been reported in archeological journals. To our surprise, we learned that Jack Hughes had excavated a picket-post house in Gray County, Texas, in 1960, a scant forty miles south of Hank's house. This site, known as Cantonment Creek, produced a structure that closely resembled both the Jack Allen house and the structure at Hank's site, and Hughes had even described it in his notes as belonging to Washita River—i.e., Oklahoma. Hughes didn't publish his Cantonment research, and our team had never heard of it before. We also took a closer look at the work Jack's son, Dr. David Hughes, had done at the "Courson Ruins" within the Buried City along Wolf Creek in Ochiltree County. As described in detail in the Buried City exhibit, the Wolf Creek ruins were best known for their large houses with thick walls made of caliche stone cobbles and adobe. Most of the structures in the Buried City complex dated between 1250 and 1450 A.D., and were thus contemporaneous with the structures of Antelope Creek. But in 1985 David Hughes began a four-year excavation of the complex, and we were interested that he found some evidence of picket-post construction. At Courson A (41OC26), the main house was a small square house with two central support posts flanking the firepit. The house was identifiable because it had burned and the butts of the posts were preserved. The structure is four meters on each side.... Walls were made of shallowly set wood posts from 4 to 12 centimeters in diameter placed up to 25 cm apart. Two main posts flanked the hearth and were set about halfway between the hearth and the northwest and southeast walls.... A radiocarbon date of.... A.D. 1210 (DIC-3281) was obtained on charcoal from a nearby feature. (From unpublished manuscript, "The Courson Archeological Projects: 1986, 1987, and 1988 Seasons," courtesy David Hughes). Our research was suggesting that the appearance of picket-post houses in the Texas Panhandle might be more than an anomaly. We now had evidence of five picket-post structures in the Panhandle: Cantonment Creek, Jack Allen, Footprint, Courson A, and Hank's site. The Oklahoma Hypothesis was looking better all the time-an orderly march of picket-post houses that began in central Oklahoma and led all the way to Antelope Creek. If we could get all the dates to line up, we might be able to make a case for a steady migration of people and ideas from Oklahoma to Antelope Creek. New DirectionsThe interpretation of (radio)carbon dates is a tricky science, even for professional archeologists who deal with them all the time. Because a single date can sometimes be misleading and since the early date on Hank's House was so important to our overall interpretation and analysis, we decided to run some more radiocarbon dates to double-check our original date. In archeological jargon, we recognized that the original date of around A.D. 1100 might reflect the "old wood problem" in which the dated sample of old tree wood does not reflect the cultural event being dated (see dating discussion in Hank 1.) The other two samples from Hank's house were carefully selected to avoid this problem. The new samples—one from the outer rings of a charred interior post and the other a corn fragment removed from the floor of Hank's house—were submitted for dating. The date on the post represents the time when the large juniper tree was cut, which most likely occurred within a year or two of the building of Hank's house. The corn was almost certainly grown by the inhabitants, and the date on this sample reflects the time the cob was harvested. These two dates came back virtually identical. The results disputed the earlier finding and gave us a later date of for the building and occupation of Hank's house, at approximately A.D. 1300, give or take 50 years. The team agreed that this was a reliable age estimate for when Hank's house was built and occupied. Suddenly we were faced with a different interpretation of Hank's house based on the new dates. Before, we had assumed that our structure pre-dated the stone structures at Antelope Creek, and might represent a transitional stage of development between Woodland and Plains Village architecture. Now, we found ourselves staring at a scenario we had never considered: the people who built Hank's House were mainstream Plains Villagers, yet didn't belong to Antelope Creek, Buried City, or Custer-Washita River. It appeared that they represented an independent manifestation of Plains Village culture that flourished at the same time. The Oklahoma hypothesis wasn't exactly dead, but the new date on Hank's House had certainly altered the orderly progression of dated picket-post structures we had been looking for. In archeology, one tries to match new discoveries with previously documented site information, in an attempt to posit relationships and cultural patterns. These relationships can be established through similarities in the artifact assemblages, pottery types, dates of occupation, analysis of human skeletal remains, and architecture. We had done a thorough search of the literature from Antelope Creek, Buried City, Custer-Turkey Creek, and Paoli-Washita, and had found similarities between all of them and Hank's site, but also important differences. Hank's house didn't seem to fit anything we found in the literature of the region. But then we took a closer look at the literature itself and realized that archeological research in our region had concentrated on three areas of heavy site density: the four Texas counties centered around Lake Meredith and the Alibates flint quarries (i.e., the core area of Antelope Creek), along Wolf Creek in Ochiltree County (Buried City), and the Custer-Turkey Creek and Paoli-Washita River sites along the Washita River and its tributaries in western and central Oklahoma. Hank's site occupied a "dead zone" where archeologists had seldom ventured, and where few prehistoric sites are documented and virtually none have been excavated. The truth was, nobody really knew much about Plains Village sites in Roberts, Hemphill, Lipscomb, Gray, or Collingsworth Counties, and that huge expanse of country represented a major gap in the archeological record. If you were wondering just how big a gap this is, these five Texas Panhandle counties comprise an area of 4,616 square miles, or almost three times larger than the state of Rhode Island. Filling the GapsThe one man who could have helped fill in those gaps had recently died: Dr. Jack Hughes, the dean of Panhandle archeology. As a professor of anthropology and geology at West Texas State University from 1951 to 1985, Jack had passed along his love of archeology to two generations of students, and nobody in the world knew more about archeological sites in the Panhandle. When he wasn't teaching, Jack had driven countless miles across the Panhandle, talking with landowners and collectors, and recording obscure sites for the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas. If anybody knew what kinds of archeological sites existed in the "dead zone" of the northeastern Panhandle, it would have been Jack Hughes. Jack was gone, but he had left behind seven large ring-binder notebooks that contained the meticulous field notes he had recorded between 1952 and 1986. The notes had been indexed and archived at the Panhandle-Plains Museum, and we were given an opportunity to use them in our research. Sure enough, the notes yielded information about many eastern Panhandle sites that Jack had visited and surveyed, only a few of which had ever been excavated and almost none that had ever been written up in the literature. In many instances, his raw field notes provided us with the only information in existence about little-known sites in the eastern Panhandle. Our study of the field notes turned up hints and fragments that added to the larger picture we were trying to reconstruct. In his exploration of sites in the eastern Panhandle, Hughes had found surface evidence of Plains Village structures that did not match the pattern of typical Antelope Creek architecture, meaning they had no stone foundations or walls. These structures gave every indication of being either pithouses, houses of picket-post construction, or some combination of the two. In the architecture and pottery, Hughes detected a cultural influence coming from the east or north, or both. He found this evidence, not in one or two locations, but in many: in Roberts, Hemphill, Hutchinson, Lipscomb, Gray, and Collingsworth Counties. The sites were on McClellan Creek, Salt Fork of the Red River, Red Deer Creek, Palo Duro Creek, and Wolf Creek. All these locations fell within our "dead zone" in the eastern Panhandle. Jack Hughes's field notes left a clear impression that he was tracking a non-Antelope Creek influence on archeology in the eastern Panhandle. Even though his Lake Creek article (1962) had laid out his case for the indigenous development of Antelope Creek people out of Woodland roots, Jack continued to look toward Upper Republican and Washita River for influences on Panhandle archeology, particularly in the eastern Panhandle. In his 1968 doctoral dissertation (Prehistory of the Caddoan-Speaking Tribes, Columbia University), Jack Hughes had argued rather strongly that the "Panhandle Aspect," as the Antelope Creek focus was called at the time, was closely related to Upper Republican groups. He spoke of Panhandle Aspect as "a southern relative of Upper Republican," "their closest relatives," and "its southern twin." He also noted that "in the eastern Panhandle are sites which lack slab structures and have both cord-paddled pottery like the Panhandle aspect and plain ware like the Washita River, Custer, and Henrietta foci to the east." Jack Hughes was a man of such enormous curiosity that he needed two or three lifetimes to organize and document his thoughts. If he'd had another lifetime, one suspects that he would have proposed a hypothesis similar to the one we were groping toward with Hank's house: that there was much more to Panhandle archeology than Antelope Creek. Odessa YatesIt happened that the Hank's site archeologists weren't the only ones who were finding gaps in the archeological record. Up on Clear Creek in the Oklahoma Panhandle, only sixty miles north of Hank's Site, University of Oklahoma archeologist Scott Brosowske was directing excavations at a site called Odessa Yates while we were working on Hank's site. The Odessa Yates site produced artifacts and carbon dates that suggested a typical Plains Village occupation. These people lived in villages, made pottery, hunted bison with side-notched points, and cultivated crops in the fertile Spur soils along waterways. Brosowske expanded his survey beyond the initial Odessa Yates location and found that the same people had occupied village sites over a wide area on Clear Creek and Kiowa Creek, suggesting a robust economy based on farming and trading. Up to this point, we might be describing Antelope Creek, Buried City, Washita River, or Upper Republican, but then comes the clinker. The houses Brosowske was excavating at Odessa Yates weren't the stone-slab structures of Antelope Creek, the caliche boulder structures of Buried City, or the rectangular picket-post houses of Washita River, Zimms, and Upper Republican. The Plains Village people at Odessa Yates were living in small circular to oval pithouses with two central roof support posts, and these structures showed evidence of vertical wall posts! Jack Hughes's field notes had clearly suggested that pithouse and picket-post construction might be far more common in the eastern Panhandle than anyone had ever dreamed. Our team had documented five picket-post structures in the eastern Texas Panhandle, and now Brosowske had found a group at Odessa Yates that lived in circular pithouses in the Oklahoma Panhandle. We were also interested in two other sites in Oklahoma: the Lonker and Stamper sites. Located some forty miles northeast of Odessa Yates, an excavated structure at the Lonker site revealed the remnants of 13 vertical posts and no evidence of stone foundations, and yielded a date very close to our Hank's house, A.D. 1257-1293. In a 1994 article, Robert L. Brooks noted that "the post mold pattern for the structure…resembles patterns occurring at Plains Village sites farther east" (Washita and Zimms) and that the Lonker structure lacked "the central channel common in Antelope Creek houses." We found it particularly interesting that Brooks was not able to assign the Lonker site to any of the known Plains Village affiliations. Indeed, he noted that of 52 Plains Village sites in Beaver and Texas Counties in the Oklahoma Panhandle, 30 "represent sites of unknown Plains Village affiliation." In 2003, Christopher Lintz began publishing a series of articles to reevaluate the Stamper site in Texas County of the Oklahoma Panhandle. Excavations at this important Plains Village site were done in 1933 and 1934 by Federal Emergency Relief Administration archeologists C. Stewart Johnson and Fred Carder. Some information was published on this work in 1950, but it was far from a full analysis and the site data had not been looked at since. Lintz reexamined the site data, and in 2003 he published the first three articles of a four-part series on the Stamper site in Oklahoma Archeology: Journal of the Oklahoma Anthropological Society (Volume 51, Numbers 2, 3, and 4; the fourth article will appear in 2004). While many pithouses were excavated and most had rock-lined wall foundations, yet another house with vertical post walls had been dug by Fred Carder in 1934. In the manuscript for part 4, Lintz presents new evidence and interpretations, and describes Structure 14B as:

All this evidence of non-stone architecture was coming out of occupation zones that were clearly identified as Plains Village and provided proof that pithouse and picket-post construction had survived into the Plains Village period of 1250 to 1450 A.D. This seemed a major departure from accepted models, and we were left wondering, Who were these people? It appeared that in the eastern portions of the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles we were finding groups of Plains Village people who followed lifeways similar to the major groups, but who had developed their own unique cultural patterns. All of this new data was coming from a region that would have been classified just a few years ago, without much thought, as being within the Antelope Creek culture area. This ill-defined area may have extended as far south as the Red River in the Texas Panhandle, and as far north as southwestern Kansas; westward to the fringes of the Antelope Creek habitation zone in the central Texas Panhandle, and eastward into the Washita River area of Oklahoma. It might include the quirky little outcroppings of culture at Buried City, the Zimms complex, Odessa Yates, Stamper, Lonker, and, perhaps, the people who built picket-post houses at Jack Allen, Cantonment Creek, and Hank's site. (However, the picket post house at Footprint, squarely in the middle of Antelope Creek core area in the central Panhandle, still doesn't make sense!) ConclusionThose of us who dabble in archeology yearn for simple answers and tidy theories that will explain what we find in the field. Our team at Hank's house has found neither, but rather far more diversity and complexity than we ever expected. It has even gotten to the point that we have dubbed the term "typical West Pasture" to refer to anything we find that doesn't fit our expectations or the widely accepted archeological models. Typical West Pasture is now a seemingly endless stream of head-scratching finds that provoke more questions than answers. The continuing work we're doing at sites in West Pasture promises to muddle the picture even more, at least for the short term. Getting back to our original question of where the architectural influences came from, we haven't proved "The Oklahoma Hypothesis," but our research has revealed a substantial eastern or northern influence in the archeology of the eastern Texas Panhandle, an influence that Jack Hughes detected forty years ago but which has been left for others to document. Did the influence come from Washita River people to the east, or from Upper Republican migrations from the north? Was there any mingling with Apishapa stone masons from Colorado? Did the people who built Hank's house have any role in the development of the Antelope Creek villages in the central Panhandle? And, were the villages in West Pasture peaceful, or were they too plagued by warfare as so many of their neighbors were? The mysteries we've exposed through our work at Hank's site may never be resolved completely, but our best hope lies in further excavation and analysis of sites in the eastern Texas Panhandle, northwestern Oklahoma, and southwestern Kansas. Until that work is done, we can make very few statements with confidence, but of one thing we are sure: there is much more to Panhandle archeology than Antelope Creek. The bibliographic references for the articles and books cited in this section can be found in in the Credits and Sources sections of the other Plains Villagers exhibits. |