| In this section:

|

The investigation of Hank's site

was an entirely volunteer effort involving professional

and avocational archeologists. Many people—including

members of the Panhandle Archeological Society and Texas

Archeological Society—joined in the effort. In

this picture, the excavators are just beginning to see

burned clay daub and charcoal. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Map of excavations at Hank's site

showing the location of the pithouse and other features.

Click on image to see full map. Graphic by Sandy Hannum,

courtesy Prewitt and Associates, Inc.

|

A cluster of stacked mussel shells

was found in the trash midden and work area in front

of Hank's house. The entire cluster was removed intact.

Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

These eight rocks were found in a

tool cache outside Hank's house. Photo by Doug Boyd.

Click to see enlarged view and detailed caption.

|

TAS members Reba and Mitch Jones

excavated Pits 1 and 2 located about 15 m away from

Hank's house. The white arrow points to Pit 1, the more

obvious of the two pits in this photo. Photo by Doug

Boyd.

|

Doug Wilkens (in foreground) looks

up from exposing the tops of the charred posts along

the west wall of Hank's house. And don't let the sunny

conditions mislead you, it was cold! Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

They always say "good help is

hard to find." Here, Mark Erickson is lying down

on the job. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

| |

Many pieces of burned daub were found

in the layer of burned debris lying on the floor of

Hank's house. This fragment of daub has parallel stick

impressions that came from small branches used to form

one layer of the roof. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

Archeologist Reg Wiseman, from Santa

Fe, New Mexico, writes notes sitting next to a clump

of Sorghastrum nutans. This is the yellow Indian

grass that was used in the construction of the roof

of Hank's house. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Looking eastward across the exposed

floor of Hank's house, the depressed interior channel

and entrance step are clearly visible. Remnants of clay

wall plaster are visible along the south edge of the

entrance and along the front (east) wall of the house.

Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Close-up view of the burned posts

and clay plaster along the back (west) wall of Hank's

house. When the posts were excavated, 20- to 40-cm-deep

post holes were found and it was clear that the back

wall leaned slightly inward—about 14 degrees off

of vertical—toward the inside of the house. Photo

by Doug Boyd.

|

John Erickson examining the exposed

charred posts of Hank's house with a bemused look on

his face. By this time, the layout of the house was

becoming clear. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

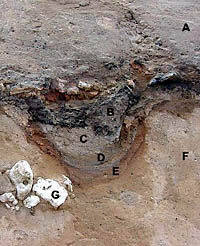

Central hearth or firepit in Hank's

house before it was excavated. The layers are: (A) upper

fill, post-occupation deposits; (B) layer of burned

branches and clay daub from roof fall; (C) blow sand

inside hearth; (D) ash layer at bottom of hearth; (E)

baked clay lining of the hearth; (F) pre-house sandy

soil into which the house was dug; and (G) caliche

rocks that are part of a natural layer of intermittent

gravel in the alluvial terrace (i.e., representing a

flood event before the house existed). Photo by Doug

Boyd.

|

An arc-shaped notch in the southern

channel lip indicates where an extra post had been placed.

The notch was cut out of the channel lip, but the post

rested directly on the floor. This may represent a repair

post that was put in to help support a sagging roof,

and it suggests that the house had been lived in for

some time. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

This small triangular arrow point

is called a Washita, a style that is common among many

Southern Plains Village groups in the Texas Panhandle

and western Oklahoma. This artifact was found along

the back wall of Hank’s house. It is discolored

and fractured by intensive heating, and it was definitely

inside the house when it burned. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

The cluster of artifacts found on

the floor of Hank's house against the south wall is

tentatively interpreted as a potter's tool kit. Click for enlarged image and more-detailed caption.

Photo

by Doug Boyd.

|

TAS member Teddy Stickney from Midland,

Texas, carefully exposes the charred branches on the

floor of Hank's house. All of the charred fragments

were collected so that the wood could be identified

later. Sediment from the floor of the house was collected

in bags for flotation to recover tiny pieces of charred

plants. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

The plum pits found at Hank's house

were lightly charred and were cracked open to remove

the edible seed inside. Wild plums grow in many places

in the West Pasture canyon and would have been an important

food resource. This photo shows a prehistoric plum pit

fragment (right) compared with a whole modern pit (top)

and a cracked modern pit (left) from a nearby plum thicket.

Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Taking notes and making sketch maps

were an important part of the excavation at Hank's site.

Here, Doug Wilkens is making notes on what he has uncovered.

To the right, Kris Erickson and Reggie Wiseman are exposing

the burned branches and daub that fell when the house

burned. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

There was no shortage of materials

suitable for dating. Large intact pieces of burned branches

were found on or near the floor in Hank's house. These

materials represent portions of the roof that burned

and collapsed onto the floor. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Sample

of charred corn cupules from Hank's house. Cupules are

the cup-shaped sockets in a corn cob that hold the corn

kernals in place. Using the AMS (accelerator mass spectometry)

radiocarbon dating technique, age estimates can be obtained

on even tiny fragments of organic material, such as

a single corn cupule. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

|

The prospect of investigating Hank's house was

exciting because its well-preserved remains offered an opportunity

to learn a great deal about the architecture of a Plains Village

pithouse. We wanted to "salvage" the information

before the next big flood completed the erosional process

and washed away the remaining half of the house. Such floods

are highly unpredictable—it might be 20 years or 24 hours

before a real Panhandle gully washer stalled over the upper

end of the West Pasture and remodeled the landscape, sending

Hank's house tumbling down the streambed. So we decided to

conduct a salvage excavation as soon as possible. But first

we had to find a crew and solve some logistical problems,

the heaviest of which (literally) was removing the thick mantle

of up to two meters (seven feet) of sand covering the pithouse.

Finding a willing crew proved easy enough once

Doug Wilkens and Doug Boyd spread the word of what we had found. The

Panhandle has a small, but active group of experienced avocational

archeologists, most of whom are members of the Panhandle Archeological

Society and the Texas Archeological Society. We also persuaded

several professional archeologists active in Southern Plains

archeology to take time "off" and join us. Meanwhile,

Erickson took care of the logistics including establishing

a field camp at the site where we could store equipment and

preparing an excavation platform along the creek cutbank.

We returned to the M-Cross Ranch in late November,

2000, with a sizable contingent of volunteers. Before most

arrived, landowner John Erickson used his small bulldozer and Bobcat to remove

the overburden (overlying sand), stopping a foot and a half

(40-50 centimeters) or so above the pithouse layer. Over the

next week, the volunteer crew put in 406 hours of labor as

we exposed most of the remaining half of the pithouse and

several of the associated features. We had hoped to finish

the dig in one session, but couldn't quite do it. In mid-May,

2001, we returned with a smaller crew for a three-day dig

to wrap things up. The rest of this section explains what

we found.

Sliced in Half

Hank's site is formally known as 41RB109, being

the 109th officially recorded site in Roberts County, Texas.

The unnamed creek through the West Pasture had, in essence,

given us the kind of view that archeologists often like to

start with—a long cross-section or slice through Hank's

site. The map on the left shows the area we excavated and

the archeological features we identified along this slice.

Before discussing the prehistoric house proper, let's look

at some of the other features we found outside the house.

Some of these were very close to Hank's house and very likely

"functionally associated," meaning they were probably

created and used by the occupants of the house. But others

are farther away and were probably part of another household—without

additional excavation we can't really tell.

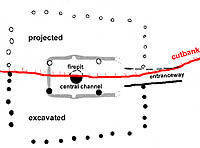

Hank's house faces east, like many Plains Village

houses, and has an extended entranceway (see house diagram

on right). We excavated around the front of the house and

found several noteworthy features. In front of Hank's house

was a trash midden, a thin sheet-like layer of household

trash —scattered bits of artifacts, such as flint flakes

and pottery sherds, mixed with dark, charcoal-stained soil.

Within the midden were three distinct groups of objects (archeologists

call such groupings cultural features), all of which indicate

that the area in front of the house—a sort of "front

porch"—was used not only for discarding trash, but

also served as a storage area and probably a work area.

Caliche Cobble Cluster: The first feature

was a cluster of unmodified caliche rocks that were probably

collected and piled with the intent of being used at a later

time.

Mussel Shell Cluster: The second was

a tightly packed cluster of six complete mussel shell valves

that had been stacked, one inside the other. These, too, appeared

to represent materials that were stockpiled for later use.

Grinding Stone Tool Cache: The third

feature within the trash midden was a tool cache of eight

rocks, seven of which were grinding tools. A "cache"

is a group of objects that were intentionally stored, perhaps

even hidden. A metate, a pestle, and five different sizes

and types of manos were found in a tight cluster and appeared

to have been stored in a small pit. These grinding implements

made up a diversified tool kit useful for a variety of different

functions. The eighth rock was a large chunk of very grainy

and poorly consolidated conglomerate. The large rounded sand

grains that comprise this rock look very similar to the grains

seen in many of the potsherds found on the site. Pieces of

this rock may have been crushed up and added as a tempering

agent to the clay used for making pottery.

Storage Pits: On the edge (as we perceived

it) of the sheet midden was the bell-shaped pit (Pit

3) found just outside the entrance to Hank's house. We found

two other bell-shaped pits 12 to 15 meters east of Hank's

house. Like Hank's house, all three of these pit features

had been sliced in half by erosion. The bell shape of the

pits is typical of underground pits used by many different

prehistoric and historic Indian groups across much of the

Great Plains, and they were typically used by farming peoples

for storing crops that were harvested in the fall for use

later in the winter. The relatively narrow entrance at the

top of the pit was necessary so that the opening could be

easily covered by a large flat rock, a flat piece of wood,

or perhaps a smoked buffalo hide cover held down by rocks

and covered by dirt. The covered pit would have been hidden

and protected from most varmints (at least until some lucky

rat dug his way into it).

Because Pit 3 was located just past the

entryway to Hank's house, it likely served as an underground

storage bin for the people who lived in the house. The pit

could have been used for many years but probably was abandoned

when some food rotted inside it or burrowing rodents dug into

it. Once the pit became useless for food storage, the people

living in the house probably filled it with household trash,

bits and pieces of which we found.

Because Pits 1 and 2 were located some distance

from Hank's house, they were probably not associated with

Hank's house and may have been used by people who lived in

another residential structure nearby. Like Pit 3, Pit 2 was

filled with cultural debris (trash) and had been converted

from a storage pit to a trash pit. In contrast, the fill inside

Pit 1 contained no cultural debris, the sediment fill inside

was very clean (there was no charcoal or ashy sediment), and

the pit outline was well defined. This may indicate that the

last function of the pit was for storage of perishable foods.

An attempt was made to identify any organic remains that might

have been stored in this pit, but none were preserved.

Architecture of Hank's House

In this section, we take a closer look at what

we found in the pithouse and what we think it means. Excavation

is a process of discovering evidence, but detailed and accurate

records must be kept so that you can study and interpret that

evidence after it is dug up. Each layer of fill in Hank's

house was carefully excavated and all artifacts and features

were plotted on excavation maps. Descriptions of the excavations

and features were written, and hundreds of forms and maps

were created. Thousands of photographs (black and white, color

slides, and digital images) were taken to document every detail

the archeologists saw. All of the artifacts were collected

in bags marked with precise location information (provenience),

and many charcoal and soil samples were taken. All of these

steps are time consuming but important because what remained

of Hank's house was destroyed in the act of excavating it.

A site cannot be reconstructed to reveal the stories of life

long ago unless such detailed records are kept and studied.

The process is similar to how forensic scientists investigate

a crime scene to learn exactly what happened.

During the excavation, we separated the sediment

inside the house into three stratigraphic layers called the

upper fill zone, middle fill zone, and floor zone. The upper

fill zone represents sediment and artifacts that were

deposited inside the depression created after the house was

abandoned and collapsed. The sediment was mainly eolian sands

that were blown in by the wind, and the artifacts were probably

thrown into the shallow depression by prehistoric people.

We suspect that the depression filled in quickly, probably

within a few years of when the house fell down.

The middle fill zone was marked by the

appearance of charcoal staining and small fragments of burned

clay daub, and these burned materials became larger and denser

throughout this zone. Large intact pieces of charred wood

and burned daub found in this zone clearly indicated the house

had burned. These materials were especially abundant in the

western portion of the house, where the burning was quite

intensive, but sparse in the east side and southeastern corner.

It soon became clear that the debris represented the materials

from the roof of the house that had burned and collapsed.

Some of the burned wood represented long segments of tree

branches, while many of the burned daub fragments had parallel

stick impressions indicating that wet clay had been pressed

onto the inside of the roof. The burned daub was most abundant

in the center of the house, indicating that lots of clay was

used to line the smoke hole above the central fire pit. The

people who lived in Hank's house must have been concerned

about the possibility of sparks from the fire pit rising and

igniting the roof.

The floor zone represents materials found

in the last 4 to 6 inches above the floor of the house. This

zone contained abundant charred wood and burned daub, mainly

in the western area, and some artifacts. Where the burning

was intensive, the floor itself was a thin layer of baked

clay sediment, and the excavators could easily follow the

floor. In this area, small hollow tubes of charred grass found

lying directly on the floor had once been part of the roof.

In the eastern part of the house where little or no evidence

of burning was observed, the floor was difficult to follow.

The unburned clay on the floor had gradually melted away (dissolved)

as water percolated down through the sandy sediments over

many hundreds of years.

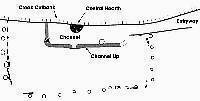

When the excavations ended, we had exposed exactly

one half of the original pithouse and the house layout was

obvious and familiar. Hank's house was similar in many ways

to other pithouses found and excavated in the Texas Panhandle,

but it also was unique in many respects. The burning of the

structure preserved many important architectural details.

Some are typical of prehistoric pithouses of the Antelope

Creek and Buried City cultures, others are not. Each of the

key architectural features of Hank's house is described below.

Clay-plastered Entryway: Hank's house

had a nine-foot-long entryway that was plastered with clay.

It began about three feet inside the east wall of the house

and extended eastward six feet beyond the east wall. It was

essentially a paved ramp that sloped from the original ground

surface at its east end down into the house, and the walls

of the entrance extended into the house at least two feet.

The ramp bottomed out just inside the house, but rose sharply

on its west end forming a hump or step that was several inches

higher than the floor or the lower edge of the entry ramp.

This was obviously a high-traffic area, and multiple layers

of clay indicated that the step had been replastered several

times. It also formed a depression in the entryway where the

bottom of the ramp met the step. Fine, laminated layers of

sediment in this depression suggest that it was a water trap

that prevented water from running into the house during heavy

rains.

West Wall: The west wall of the house

was the best-preserved architectural feature because it had

been intensively burned. Along the west wall, eight wooden

posts had been completely charred and clay wall plaster between

them was burned and still in place. Below the floor level

there were six post holes, round to oval in shape, found beneath

charred posts. The two burned posts that did not have corresponding

postholes were resting directly on the floor and had not been

set into the ground. The posts ranged in size from 3 to 4

inches (7 to 11 cm) in diameter, and from 8 to 16 inches (20

to 40 cm) in depth below the floor. In cross-section, some

charred posts were round and had been complete logs or branches,

while others were arc-shaped (half branches) or thin slats

that represent split branches. It is quite possible that wood

was scarce enough that the builders split some branches to

conserve their lumber. The west wall plaster and charred posts

were preserved to a height of about 2 feet above the house

floor. Most of the posts were burned down only to the floor

level, where the fire probably stopped due to lack of oxygen,

but a few posts were charred down below the floor level and

deep into the postholes. Such burning is not common, but modern

ranchers have seen wooden fence posts burn down deep into

the ground in some cases.

South wall: Eight post holes were found

along the south wall, but only one remnant of a charred post.

The post closest to the southwest corner of the house had

been burned in place, but only a small portion of it was found

above the floor level. It appears that the intensity of the

fire was greatest in this corner, but the burned debris found

on the floor diminished toward the east. Three large flat

chunks of burned clay were found along the south wall near

the southwest corner of the house. These appear to have been

remnants of clay plaster from the wall, and two of the pieces

appeared to be in place along the south wall. The post holes

along the south wall ranged from 7.5 to 17 inches (9 cm to

43 cm) deep below the floor level. Based on the diameters

of these postholes, the posts were probably about the same

sizes as those on the west wall—about 3 to 4 inches

(7 to 11 cm) in diameter.

East wall: The east wall was marked by

five post holes but no charred posts were found. Remnants

of wall plaster were found adjacent to and near the entryway

step. The absence of burned posts and scarcity of burned wall

plaster indicates that the fire was not very intense toward

the front of the house. The east wall post holes ranged from

7 to 12 inches (18 to 31 cm) deep below the floor level. These

posts were probably about the same sizes as those along the

west wall.

SW Central Post: This was a very large

post, set deeply in the ground. This post was very obvious

to the excavators because a large chunk of a burned log, measuring

nearly 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter, was preserved and stuck

up several inches above the floor level. This large post had

burned in place, but the burning stopped just below the floor

level. When a deep test was excavated through the floor to

reveal the profile, the post hole was 10 inches (25 cm) wide

at the top and tapered to a point at a depth of about 24 inches

(60 cm) below the floor level. The tip of the post had been

charred before it was set into the ground.

SE Central Post: We almost didn't find

this posthole—a fact that serves as a cautionary note

to archeologists digging pithouses like Hank's. As we excavated

Hank's house, it seemed to be following a pattern of interior

features that was similar to that of other pithouses in the

Antelope Creek area. Once the southwest central post was found,

it seemed logical that there must be a corresponding southeast

central post. But when we reached the floor level at this

location, the expected burned post or a posthole wasn't there.

Instead, it seemed to be a continuous floor surface. Some

burned debris was across the floor in this area, and there

were lots of rodent burrows, but there was still no hint of

this post hole as we troweled through the floor. We joked

that it was obvious the Indians must not have read an archeological

report on how their house should have been built.

Puzzled, we kept on digging below the floor

with our trowels because we were convinced that there had

to be a southeast central post to support the roof. It was

not until we had dug a full 4 inches below what appeared to

be an intact floor surface that the first hint of a post hole

was seen. At this point, we found a circular stain that measured

about 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter. We then dug a small pit

down below the floor to create a profile and found that the

posthole extended down 20 inches (50 cm) below the floor level.

Like the southwest central post, the tip of the southeast

central post had been charred before it was set into the posthole.

Central Firepit: In the very center of

Hank's house was the firepit or central hearth. The hearth

was created by digging a large, bowl-shaped pit and lining

it with clay plaster. When viewed from above, the hearth appeared

as a circular pit ringed by a ridge of clay that was about

5 cm higher than the surrounding floor. The outside diameter

of the clay ridge was 20 inches (50 cm), and its inside diameter,

the mouth of the pit, was 18 inches (45 cm). When viewed in

profile, the hearth had a deep bowl shape and tapered to a

rounded bottom that measured about 11 inches (28 cm) in diameter.

The pit was 11.5 inches (29 cm deep).

Several layers of fill were evident in the firepit.

The layer of burned debris across the floor of Hank's house

extended down about 4 inches (10 cm) into the hearth pit.

This represented roof fall material from when the house burned.

Below that was a layer of brown clayey sand, 4 to 5.5 inches

(10 to 14 cm) thick, that looked like wind-blown sand. On

the very bottom was a 4- to 5-inch (10 to 13 cm) thick layer

of gray ash, presumably from the last time the hearth was

used. At the top of this ash layer, a single sherd of cordmarked

pottery was found.

The clay layers that lined the hearth were interesting.

There was some hint of lamination, suggesting that several

layers of clay might have been added at different times. There

also was an outer layer of clay that was definitely added

at a later time. Several inches of clay had been mounded up

to reform the rim of the hearth, and this added layer extended

about half way down inside the hearth before abruptly ending.

Central Channel: Hank's house had a distinctive

depressed floor area in its center. If the house were complete,

it would have formed a rectangle with a central roof support

post at each corner. Often called a central channel, the rectangular

area around the hearth was about 4 inches (10 cm) lower than

the surrounding floor. Such depressed floor areas are common

features in many Antelope Creek houses, but its precise function

is not known. Archeologists have speculated that it may have

helped with airflow around the central hearth, and it might

have served as a water trap to keep most of the house dry

if water seeped (or poured) inside during heavy rains. The

central channel also served as the main kitchen and living

room, around which people would do many different activities.

The area around the channel would have been used for storage

of belongings and sleeping areas.

Post Notch: An arc-shaped notch was found

along the southern channel lip, about half way between the

southwest and southeast central posts. This notch appears

to have been added sometime after the house was initially

built, presumably to accommodate the bottom of a vertical post.

It may mean that the house was used for several years, at

least long enough for the roof to begin sagging and require

an additional support post.

Artifacts

The artifacts recovered from Hank's site can

be classified into six groups based on how they were associated

with the house:

Post-Occupation Fill: artifacts found

in the upper levels of sediment inside the pithouse. These

materials probably represent trash from occupations of other

houses nearby that was thrown into the pithouse depression

after Hank's house was abandoned.

House Refuse: artifacts found in the

sheet midden in front of the entrance to the house. These

materials were probably used and discarded by people who lived

in Hank's house.

House Storage: artifacts associated with

the three storage/cache features found in the midden area.

House: artifacts found on or near the

floor of Hank's house. These materials represent items used

by the inhabitants of the house.

Pit 3: artifacts found inside Pit 3.

These materials were probably used and discarded by people

who lived in Hank's House.

Pit 2: artifacts found inside Pit 2.

These materials were probably used and discarded by people

who lived in a separate house nearby.

Several of us involved in the dig along with

some outside specialists are still studying the artifacts

and samples from Hank's site. Proper analysis takes time and

isn't considered complete until a final technical report is

prepared. Since this is a volunteer effort, we work on it

as we can and keep chipping away at it, bit by bit. Some of

the artifacts in the house assemblage are important for understanding

the people who lived in Hank's house and are mentioned here.

The house assemblage is really very small, and

it was obvious which artifacts had been in the house when

it burned. A few flakes of Alibates flint, some turtle bones,

and some fragments of cordmarked pottery were found directly

on the house floor. A Washita arrow point was found in a mass

of burned debris along the west wall. It is also made of Alibates

flint but is permanently discolored due to the intensive heating.

Because its tip was broken off, it seems likely that someone

had brought an arrow home to take off the broken point and

lash on a new one. The broken point was probably discarded

or lost in the house.

One feature found on the floor of Hank's house

is a cluster of artifacts found along the south wall. This

group of artifacts consists of two bone tools, a mussel shell

scraper, a rounded caliche pebble, a rounded silicate pebble,

and a flake with a worn edge. All of these tools were found

in a small pile, as if they had been intentionally laid there

or perhaps inside a rawhide bag or small basket (which subsequently

rotted). Although we can't say for sure what these artifacts

represent, my working hypothesis is that they represent a

"potter's tool kit." Such tool kits were groups

of implements that would have been used to make pottery.

The pottery we've found at Hank's site doesn't

match the thin Borger

cordmarked pottery found in Antelope Creek sites. Most

of it is relatively thick-walled and is tempered with chunks

of scoria, a locally available volcanic rock. Scoria tempering

has not been reported from most Plains Village sites, and

was once regarded as a diagnostic trait of Woodland-period

pottery. We're finding scoria-tempered pottery all over the

West Pasture, and its presence in this area makes perfect

sense because large chunks of scoria are found in the upland

gravels along much of the Canadian River valley in the eastern

Texas Panhandle.

The local scoria is a dark red to black, porous-looking

igneous rock full of little air pockets that form tiny holes

along its edges. It is, in fact, a volcanic slag ejected out

of a volcano during an eruption. The most important characteristics

of the local scoria are that the weathered nodules are easy

to crush up, and the tiny bits of rock have sharp angular

edges and make excellent temper for binding clay together

in pottery making.

In the West Pasture sites, scoria-tempered cordmarked

pottery is found in contexts that are definitely Plains Village,

such as on the floor of Hank's house and in the trash-filled

storage pit nearby. Jack Hughes reported finding it at a number

of Plains Villager sites in the eastern Panhandle. David Hughes

also noted scoria tempering in some of the ceramics at Buried

City. Thus it appears to be a common pattern in the eastern

Texas Panhandle and a continuation of a more widespread Woodland

pattern.

Special Samples

Besides the artifacts recovered from Hank's

site, many samples of charred materials and sediment (from

soil or fill layers) were collected. Sediment samples were

processed using the flotation method to recover charred plant

remains. All of these samples were then examined by Dr. Phil

Dering, then with the Archeobotany Laboratory at Texas A&M

University (Dering now has his own independent lab in Comstock,

Texas). Many of the charred samples were of wood or grass

that was part of the house and are discussed below. Other

charred samples from the floor of the house, the storage pits,

or the trash midden in front of the house represent plant

foods eaten by the people who lived there. Several charred

fragments were identified as corn (Zea may) and indicate

that the inhabitants were farmers. Corn has been found in

the village sites of the Antelope Creek and Buried City peoples,

but this is the first time corn has been found in a village

in the eastern half of the Canadian River valley. Corn remains

were found on the floor of Hank's house and in the trash-filled

storage features (Pits 2 and 3).

Besides the corn, lots of fragments of charred

sunflowers seeds were found on the house floor and in the

central hearth. Because the seeds were all very small, we

know that these were from wild sunflowers rather than the

larger domesticated varieties. Plum pits also were found,

particularly in the trash midden area in front of Hank's house.

It was difficult to determine whether they were unburned or

burned, but a few appear to have been roasted lightly, with

the pits having been broken open to get at the tiny seed inside.

Another interesting find in Hank's house was

a burned clay mud-dauber's nest. This nest was built by flying

wasps, probably the black and yellow mud-dauber (Sceliphron

caementarium). Using mud from the creeks, they create

organ-pipe nests composed of multiple tube-shaped cells. The

wasps lay an egg inside each cell, and they add a collection

of tiny spiders, still living but paralyzed by venom. When

the egg hatches, the wasp larvae feeds on the spiders until

it matures and breaks out of the cell. Mud-daubers commonly

build their nests in protected areas, such as underneath the

overhanging eaves of houses or barns. Because mud-daubers

have two generations of offspring a year—one in the winter

and one in the summer—the nests found in prehistoric

sites are not good indicators of the seasons when occupations

occurred. The mud-dauber nest found at Hank's house has one

sealed tube and one open tube, but it is not uncommon for

larvae to never mature and emerge, and mud-dauber nests may

survive intact for several years unless people remove them.

These mud-daubers are not particularly aggressive, but people

at Hank's site would have viewed them as pests because their

stings are rather painful. Mud-dauber nests are very common

in abandoned houses, and the burned nest found inside Hank's

house would have come from the inside. Although it is not

conclusive, this could be evidence that the house had been

abandoned for at least a few months in the winter or summer

before it burned.

Dating: When was Hank's House Built?

Three radiocarbon dates provide the best

evidence of when Hank's house was built. The first date was

obtained from a large chunk of charred wood taken during the

initial site investigation. This sample represented wood from

the roof of the house that burned and collapsed onto the floor,

but we believe the date on this sample is too old because

of the old wood problem. To illustrate the old wood

problem, bear in mind that the radiocarbon dating method measures

the time elapsed since an organism, a tree in this case, died

rather than the time elapsed since the burning episode. This

is because living organisms continue to "cycle"

atmospheric carbon and accumulate tiny fractions of radioactive

carbon-14 (C14). Once they die, the accumulated C14 slowly

decays, or breaks down, from its radioactive form into nitrogen-N14.

By measuring the ratio of C14 to stable carbon isotopes C12 and C13,

we can estimate the elapsed time since the organism died.

Since the first sample from Hank's was only

a section of a burned branch, it may have been from the core

of the branch rather than the outer rings. Since the interior

core wood of a tree branch is dead while the outer rings are

living, a date on core wood could be much older than the actual

time the tree died. Unfortunately, there is often no way to

evaluate this. It also is possible that the sample represents

old wood that was used long after the tree had died. If a

branch that had been dead for many years was used in the construction

of the roof of the house, a radiocarbon date from it would

be much older than the actual time when the house was built

and used. Keep in mind that in circumstances where wood is

scarce, like the Texas Panhandle, prehistoric peoples often

reused the timbers of old houses to build new houses. Such

recycled timbers protected inside a house could be tens or

even hundreds of years old. It is not uncommon to encounter

situations where a radiocarbon date representing the death

of a tree is many years older than—even a century or

two before—the actual event that an archeologist is trying

to date.

When we got back the first date in the fall

of 2000, we had no reason to doubt it, but we knew from experience

that it is risky to rely on a single radiocarbon date. Radiocarbon

dating is a statistical estimation technique and any statistician

knows that the larger your sample size, the more confident

of the estimate you can be. In our case, "large sample

size" meant getting more than one date, and that is exactly

what we did. So two more dates were run; this time we were

careful to minimize the risk of the old wood problem.

The other dates are better indicators of the

true age of Hank's house. The second date was from the

outer rings of the large juniper post found in the house.

While the 8-inch-diameter post is composed of many tree rings,

only the outermost ring was living at the time the tree was

cut. By selecting a sample of only the outer two or three

rings, the radiocarbon date will represent the last two or

three years of the tree's life. The third date was on charred

corn cupule fragments recovered from the floor of Hank's

house. Since corn plants only live for one year, the radiocarbon

date on this sample represents the year the corn cob was harvested.

It is likely that the corn cupule was burned when the discarded

corn cob was used as fuel and trampled into the floor the

same year that the plant was harvested. The corn fragment

was trampled into the floor where it lay for about 700 years

until archeologists dug it up.

|

View looking to the northwest at

the start of the excavations at Hank's house showing

the setting in the West Pasture valley.

Click images to enlarge

|

The layer of burned debris was exposed

all along the cutbank edge just above the floor of Hank's

house. In order to make the work easier, a frame of

vertical posts and horizontal 2 x 6 inch boards was constructed

to create a work platform along the cutbank. Photo by

Doug Boyd. |

Diagram showing excavated and projected

house outline and features. Red line shows cutbank.

Graphic by Sandy Hannum, courtesy Prewitt and Associates,

Inc. |

A cluster of large caliche cobbles

found in front of Hank's house. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

| |

This photo shows three of the eight

rocks in the grinding stone tool cache found in front

of Hank's house. All eight specimens appeared to have

been placed inside a small pit. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

Reba (in back) and Mitch Jones excavating

the surviving half of Pit 3, found just outside the

entrance to Hank's House. This had once been a bell-shaped

storage pit but it had been backfilled with trash—probably

by the people who lived in Hank's house. Photo by Doug

Boyd. |

Archeologists excavating Hank's house

in November, 2000. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

| |

Some of the charred branches found

on the floor area were at right angles, as if they were

still lashed together when the roof burned and collapsed.

Photo by Doug Boyd. |

As the excavations reached the floor

level, archeologists spotted small hollow tubes of burned

grass and took lots of samples. They looked like the

yellow Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans) that

grows on the site today, and this identification was

later confirmed. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

Plan map showing the excavated half

of Hank's house and all of the architectural features

that were found. Click to see larger version with an

inset drawing of the projected reconstruction of what

the entire plan would have looked like. Graphic by Sandy

Hannum, courtesy Prewitt and Associates, Inc. |

The wooden posts along the back (west)

wall of Hank's house were burned in place, and the layer

of clay plaster between the posts was well preserved.

The posts were spaced rather evenly, each being about

15 to 25 cm apart. The floor of the house is visible

in the foreground. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

A large chunk of the southwestern

central post was burned at the floor level and was identified

as juniper wood. Below the floor, the posthole could

be traced downward 60 centimeters (24 inches). At the

bottom of the posthole, the tip of the post was pointed

and outlined with charcoal. This shows that the people

who build Hank's house intentionally burned the tip

before setting it into the ground to deter the wood

from rotting and insects from feeding on it. Photo by

Doug Boyd. |

This wall post (just to the left

of the striped photo stick) burned into the ground,

but the charring did not continue all the way. The pointed

soil discoloration below the charred section shows the

shape and extent of the original sharpened post. Photo

by Doug Boyd. |

After being completely cleaned out,

the deep-bowl shape of the firepit (central hearth)

is obvious. The hearth had been lined with clay originally,

but a second layer of burned clay plaster had been added

at some later time, probably to repair the firepit as

it wore down. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

Overview of the exposed architectural

features inside Hank's house. The excavation is down

to the floor over much of the house. Interior features

are: (A) central hearth; (B) charred log of southwestern

central post; (C) charred posts and plaster along the

back (west) wall; (D) location of the southeastern central

post (it had not been found at the time photo was taken);

(E) entryway step; (F) entrance ramp; and (G) remnants

of clay plaster along the entryway and front walls.

The 1-meter-long photo scale is lying inside the depressed

central channel. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

This group of artifacts was found

lying on the floor along the south wall of Hank's house.

They were badly burned during the house fire. These

artifacts—two elongated bone tools, a mussel shell

scraper, a rounded caliche pebble, a rounded silicate

pebble, and a flake with worn edge—might have been

inside a small bag or basket that burned completely.

Photo by Doug Boyd. |

This photo shows all of the artifacts

that were found in Pit 3, the bell-shaped storage pit

just outside the entrance to Hank's house. These artifacts

were discarded as trash into the pit, probably by the

people who lived in the house. The items, which include

seven flakes, two bone fragments, and a pottery sherd,

represent typical household trash. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

Small charred fragments of corn "cupules,"

the cup-shaped pieces of cobs that seat the corn kernals.

All corn fragments were recovered by the flotation method,

a technique of taking soil samples and bathing them

in bubbly water so that all of the charred plant remains

float to the top. This technique is used to recover

fragile materials that are often destroyed by sifting

soils through metal screens. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

| FAQ:

What is Flotation?

Flotation is a recovery technique that

archeologists and specialists use to separate.... read

more>> |

Scoria, a locally available volcanic

rock, was used for pottery temper by the villagers who

lived at Hank's site. The local scoria is a dark red

to black, porous-looking rock full of little air pockets

that form tiny holes along its edges. It is, in fact,

slag ejected out of a volcano during an eruption. The

most important characteristics of the local scoria are

that the weathered nodules are easy to crush up, and

the tiny bits of rock have sharp angular edges and make

excellent temper for binding clay together in pottery

making. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Scoria fragments are apparent in

the broken edge of this cordmarked pottery sherd from

Hank's site. Photo by Doug Boyd.

|

Comparison of burned mud dauber

nest (right) found on the floor of Hank's House with

a modern example (left). Mud daubers, a type of wasp,

build their nests by collecting wet mud and shaping

it into cylindrical tubes, or cells, within which eggs

are sealed. The modern example is a single cell, but

the 700-year-old nest found in Hank's house contained

four cells, one of which is complete and still sealed.

The nest survived because the mud was baked when the

house burned. Photos by Doug Boyd.

The top row shows the "front" view of the

nests, while the bottom row shows the back of the nests.

On the back side of every mud dauber nest is an impression

of the material to which it was attached. In the lower

left, the modern nest is flat because it was attached

to a piece of cut lumber. In contrast, the back of the

nest from Hank's house (lower right) has impressions

of grass and sticks, suggesting that it was probably

attached to the underside of the roof of the house.

|

This flowering cholla, like all living

organisms, continuously "cycles" atmospheric

carbon, including tiny fractions of radioactive carbon-14

(C14). Once an organism dies, the accumulated C14 slowly

decays (breaks down) into the stable form, C12. Since

the decay rate is known (C14 has a half-life of 5,730

years), the ratio of C14 to C12 in a sample of dead

organic material, such as charred wood, allows the calculation

of a statistical estimate of the elapsed time since

death. Photo by Kris Erickson. |

This section of half a juniper tree

illustrates the "old wood" problem nicely.

During its life, the tree had developed two lobes and

had split naturally near its center. The wood making

up the outer rings (far left) is decades younger than

the old, heart wood at the center (far right). Photo

by Rolla Shaller, courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical

Museum. |

The charred portion of the southwestern

central post was jacketed in dental plaster so that

it could be safely removed from the ground. Portions

of the outer rings of the log were removed in the lab

and used for radiocarbon dating to determine when the

juniper tree was cut down. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

|