A floating magnetometer is pulled behind a boat through the waters of Matagorda Bay in an attempt to locate the shipwreck.

|

Divers on the small exploration boat, Anomaly, prepare to probe the muddy bottom of Matagorda Bay to determine the source of a magnetic signal picked up on the magnetometer. Although the bay was less than 12 feet in depth, the waters were "black as midnight" on cloudy days.

|

Gradually we begin to realize that something extraordinary had happened to La Belle. Mud had encapsulated the bottom of the hull, resulting in exceptional preservation. Her cargo was largely intact, still contained in wooden barrels and boxes, many of which were exactly where La Salle and his men had loaded them three hundred years before.

-James Bruseth and Toni Turner in "From a Watery Grave" (Texas A&M Press 2005)

Principal Investigator James Bruseth excavates a trader's chest filled with glass beads.  |

Hundreds of brass hawkbells, a poupular 17th-century trade item, gleam amid the mud in the cargo hold. |

|

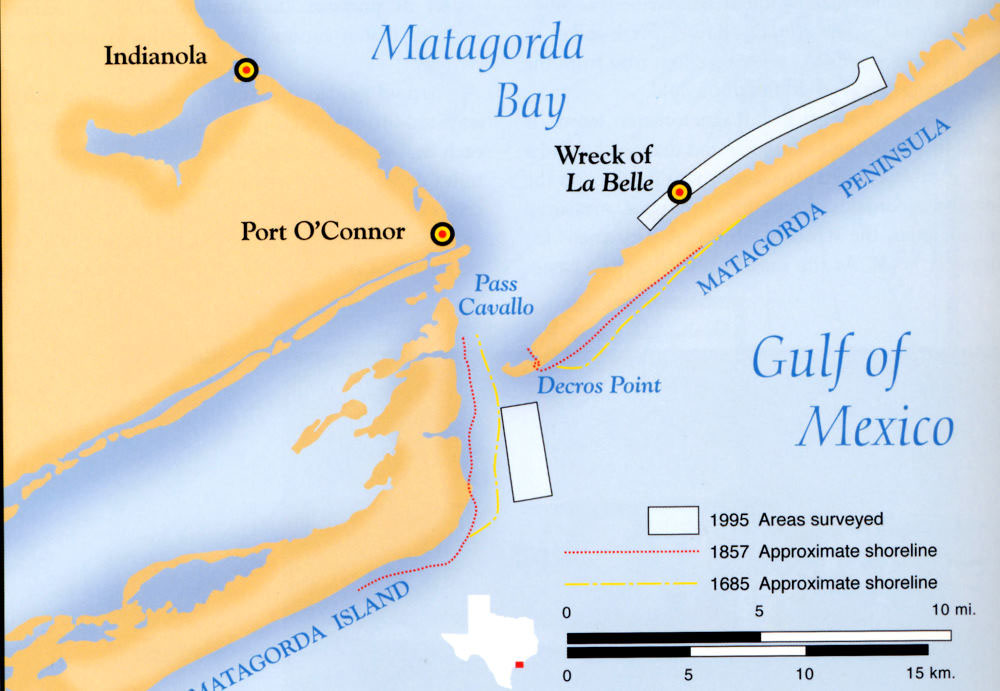

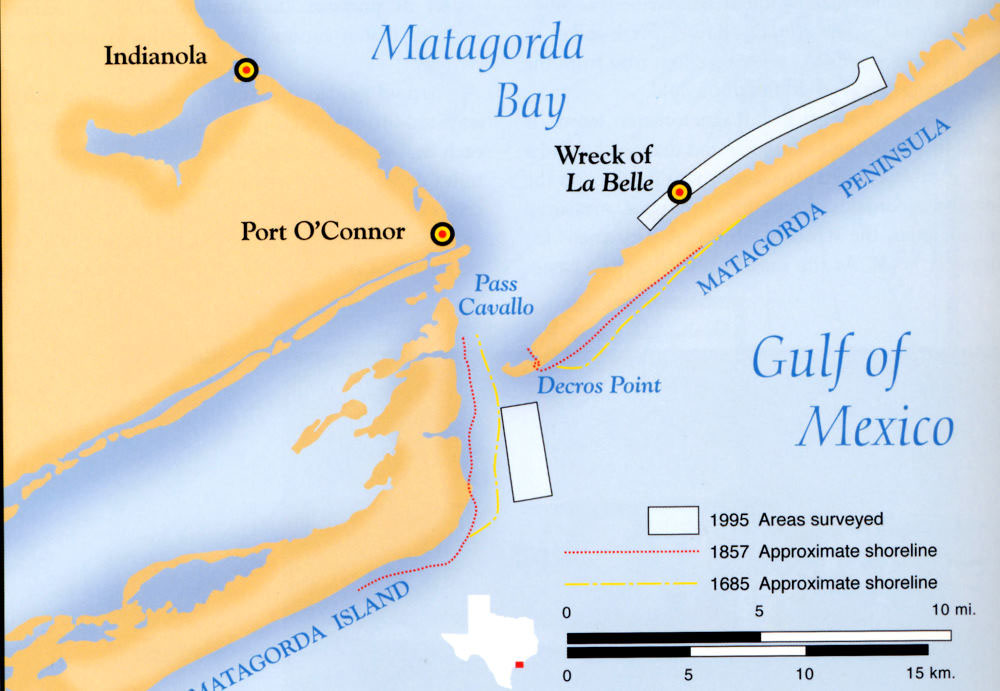

In the late 1970s, following years of research in historic archives, archeologists from the Texas Historical Commission began searching for the Belle shipwreck within the murky waters of Matagorda Bay. Historic accounts and maps drawn during 17th-century Spanish expeditions marked this relatively shallow body of water as the location where the ship had gone down in 1686. Using a floating magnetometer sensor —an electronic device that records anomalies in the earth's magnetic field caused by iron objects in the ocean floor —pulled behind the small craft, Anomaly, the archeologists scanned the bay for indications of the shipwreck. Divers, led by then-State Marine Archeologist J. Barto Arnold, checked promising signals here and there. During the 10-week effort, other shipwrecks were located, but not La Belle.

In 1995 Arnold, working with THC Archeology Division head James Bruseth, and armed with improved electronic surveying equipment, returned to the bay for a final attempt to locate the French shipwreck. Over several weeks, areas of unusual magnetism were detected and checked by divers. Small finds were brought to the surface: a belt buckle, bottle glass, rusted metal fragments. They probed one large anomaly, which appeared to be part of a wooden ship, buried in the mud.

There are many shipwrecks off the Texas coast, so this find was not, in itself, particularly unusual. Further, since it was made of wood—a material that typically does not preserve well underwater— it surely could not be very old. But then they found something very puzzling: lead musket balls, which date to at least 150 years old. Also called lead shot, this ammunition was used in flintlock muskets, which were replaced in the mid-19th century with more sophisticated guns. The divers knew they had found something historic, but now they needed something that would help them date it more precisely.

When diver Chuck Meide discovered a heavy, tubular metal object, the archeologists knew their luck had dramatically changed. Lifted carefully to the surface by a crane and barge, the heavily encrusted object was revealed as a beautiful bronze cannon, its handles cast gracefully in the shape of leaping dolphins. A raised inscription in French with the crest of the 17th-century French King Louis XIV and the crossed insignia of Le Compte de Vermadois, Admiral of France from1669 to 1683, decorated the cannon's barrel. The artifact was clearly French, and of the correct time period.

Subsequent dives revealed other evidence confirming the find: ceramic vessels; brass bells and pins intended as trade items for the Indians; wooden barrel staves; and the hilt of a sword. After 17 years of searching, the archeologists knew they had finally found La Belle. To their further astonishment, they were to discover that a large portion of the ship's hull was preserved intact—a small miracle, given that the wreck was located in an area of active oil exploration and only a few hundred yards from a busy shipping channel used by boats and barges.

Excavating in "Dark Water"

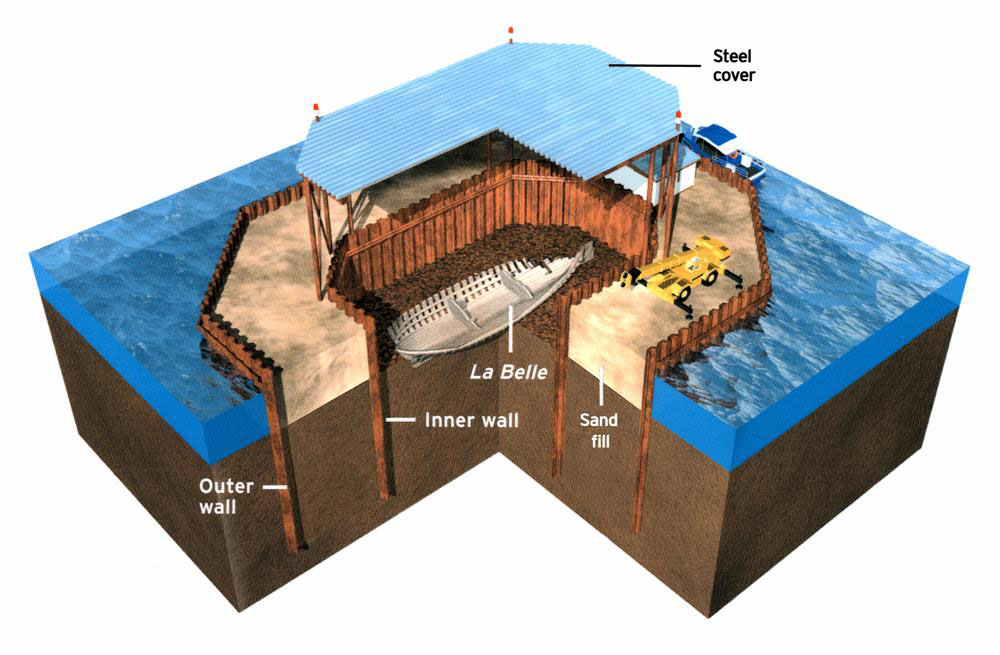

The amazing discovery triggered months of debate over how to salvage the shipwreck. Archeologists and engineers were concerned not only about how to excavate the fragile remains but how to protect them from looters once word spread about the find. Moreover, the perishable remains, having been encased in sediment underwater for some 300 years, would need immediate conservation once exposed to the air to prevent deterioration. An additional concern was the murkiness of the bay water. Although the wreck was submerged only 12 feet or so beneath the surface, visibility was poor, particularly on cloudy days. Even experienced archeologists could miss small items when excavating in what they call "dark water."

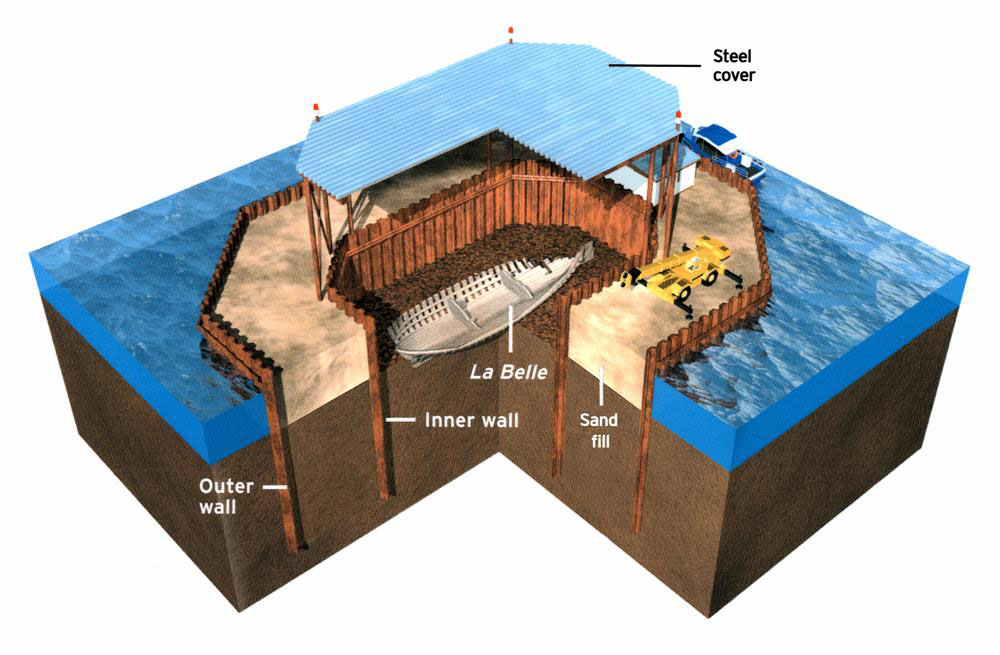

For all these reasons, it was decided that the ship would be excavated in its entirety within a specially designed metal cofferdam. The enormous building in the bay would effectively hold back the waters while archeologists carefully dug the shipwreck. This would enable the crew to excavate the site within a single season and thus constantly safeguard the remains. Although nautical archeologists were prepared for the effort, it became evident that traditional field archeologists trained on dry land were required. Once the water was pumped out, the operation would effectively become a terrestrial excavation. But it was to be the first time this type of excavation was attempted in the Americas, and it came with a complex set of problems.

In addition to conceptualizing and designing the unusual building, money had to be raised to actually construct it. In an extraordinary outpouring of support, Texas foundations, companies and citizens pitched in to back the effort. The cofferdam was to become a reality.

Nearly six months were spent building the enormous structure. Two concentric walls of interlocking steel sheet piling, each measuring roughly 57 feet long and 3 feet wide, were driven 40 feet down into the bed of the bay to encircle the shipwreck. Sand—tons of it—was then poured into the 33-foot gap between the pilings to form the wall of the coffer dam, a composite barrier intended to keep the seawater out. Once the building had been drained, however, a steady flow of leaks began. Sump pumps were set up in the bottom of the cofferdam to constantly drain water out and keep the work area reasonably dry. Screening stations and a small office were set up on the cofferdam wall. The whole structure was then covered over with a roof to provide shelter for the crews and protect the exposed wreck. The cofferdam was complete.

Something Extraordinary

Excavations began in September 1996 and stretched over nearly eight month—a period that encompassed the Gulf Coast's volatile hurricane season. With THC archeologist James Bruseth serving as Principal Investigator and Mike Davis overseeing day-to-day operations as project archeologist, crews of 20 people worked seven days a week to excavate the hull and its contents. The early results of their work, however, did not look promising, and there was concern that the few artifacts they were finding might not justify the money and time spent on the complicated cofferdam construction. But as they dug further, more and more artifacts began to appear—lead shot , beads, and fragments of rope that surprisingly had been preserved in the sediments.

As Bruseth and Toni Turner later recounted in their book, From a Watery Grave, "Gradually we begin to realize that something extraordinary had happened to La Belle. Mud had encapsulated the bottom of the hull, resulting in exceptional preservation. Her cargo was largely intact, still contained in wooden barrels and boxes, many of which were exactly where La Salle and his men had loaded them three hundred years before. We now suspected that what we were going to find would be extremely significant to North American archaeology." |

Map of Matagorda Bay showing areas surveyed with magnetometer in 1995. Illustration by Roland Pantermuehl.

|

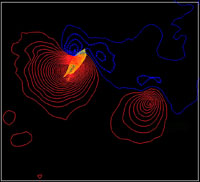

Contour map of magnetic anomalies pinpointing the position of La Belle shipwreck in Matagorda Bay.  Scanning Underwater

The wreck of the Belle was discovered during a magnetometer survey conducted by the Texas Historical Commission. A magnetometer is an electronic device that measures the strength of the earth's magnetic field. It is towed behind the survey boat and the data are collected on a computer during the survey. Iron and steel objects will cause a distortion of the magnetic field and that distortion is called an anomaly. Read more |

Cutaway view of cofferdam showing elements of construction. The walls, while not completely watertight, provided a barrier against bay water from entering the site. Small steady leaks were handled by constantly running sump pumps. Archeologists maintained a small office atop the walls form which they managed the complex project. Illustration by Clif Bosler, courtesy of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

|

A storm moves into Matagorda Bay, an eery reminder of the disastrous weather event that wrecked La Belle more than 300 years before. Archeologists assigned to overnight duty on the cofferdam spent harrowing hours riding out similar storms.

|

Wooden boxes filled with trade goods for the native peoples were remarkably preserved in the ship's compartments. All items were tagged with labels indicating a specific lot number and provenience, then carefully documented in photos, drawings and notes.

|

|