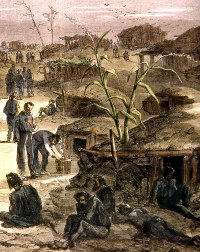

Prisoners lie along the pathways lined

with crude dugout houses at Camp Ford. Housing was described

by one detainee as being small, dark, and dirty "log

shanties" that were "partly burrowed and partly

built." Hand-colored period drawing from Harper's Magazine,

courtesy of Alston Thoms.

Click images to enlarge

|

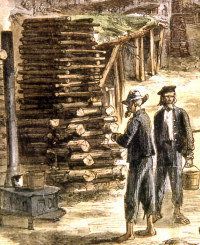

Civil War-era sketch of enslaved African

Americans building a stockade similar to the one at Camp Ford.

Drawing on file at Library of Congress.

|

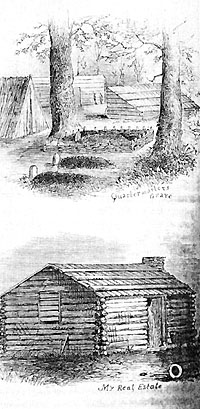

A variety of structures for shelter and

outdoor living were erected at the camp, leading one former

prisoner to write later, "What odd contrivances for shelter!

Here upright sticks sustain a simple thatch of leaves; there

poles fixed slantwise and overlain with bark, compose an Indian

lodge…Another's dwelling is of basket-work wrought out

of ashwood peelings." Drawing courtesy of Alston Thoms.

|

Escape attempts were periodically tried,

perhaps as a salve for boredom at the camp. This sketch by

a Union prisoner shows two of the approximate tunnel locations

along with other camp structures. Dotted lines indicate stockade

walls as defined by Texas A&M archeologists during investigations

in 1997. Drawing courtesy of Alston Thoms.

|

Camp Ford POWs from the 19th Iowa after their

release and return to New Orleans. Photo, courtesy of Alston

Thoms. |

|

Established in 1862 as a training camp for new Texas

Confederate recruits, Camp Ford was to have its mission dramatically

altered in barely a year's time. Union forces began to press the

Texas-Louisiana border and along the coastline near Galveston and,

in the ensuing actions, hundreds of Union soldiers were captured.

With no Confederate POW camp near at hand, Camp Ford was chosen

to receive the detainees. The first Federal POWs—fewer than

100 soldiers and sailors—arrived there in July 1863 to find

that few provisions had been made for their confinement. Many of

the prisoners constructed crude dugouts in the hill slopes to provide

themselves shelter; Confederate guards encircling the perimeters

of the small encampment served as the only deterrent to escape.

Arrival of more than 400 POWs in the following November

led to the construction of a log stockade that enclosed three acres

and a springfed creek. Within a 10-day period, a wood stockade was

raised using the labor of some 600 African-American slaves, pressed

into service from area plantations. Records suggest that captured

African American soldiers and sailors, who were not recognized as

POWs, were used as well as. POWs built their own living quarters—typically

log houses called "shebangs"—inside the stockade.

One prisoner housed in the original stockade described the bleak

encampment as: "…four acres-barren of timber and grass.

Sand blows desperately."

Following several defeats of Union forces in Louisiana

and Arkansas during the spring of 1864, more than 4,000 Union soldiers

were captured. Orders were issued to accommodate a new influx of

prisoners at Camp Ford. Over a two- or three-day period, several

hundred slaves labored to enlarge the stockade to encompass a 10-

to 16-acre area.

Although living conditions in the camp had been comparatively

good when the prisoners numbered only 100 to 250 per acre, they

deteriorated after April, 1864, when 400 or more men became crowded

into each acre of the newly enlarged camp. One prisoner wrote that,

soon after their arrival, the new POWs began to "arrange their

bivouacs into streets and began to amass green boughs for wigwams

or dig dark cavernous vaults for troglodytic dwellings." The

camp, he wrote, soon took on the aspect of a "wigwam metropolis."

Given the slope of the terrain, periodic rainstorms frequently turned

the encampment in a muddy and gully-ridden quagmire.

Original stockade at Camp Ford, as drawn by Col.

A.J.H. Duganne, a Federal POW at the camp. The prisoners eventually

built hundreds of structures at the camp—cabins, pithouses,

and dugouts. Note that, according to map key, housing was according

to mess assignment.

During the final years of its short-lived existence,

Camp Ford took on a more orderly appearance, what one prisoner described

as resembling "a very young prairie town." Streets were

laid out and lined with log structures, a parade ground was cleared,

and a market place under a pine-bough arbor was established.

Even so, boredom and a desire for freedom apparently

occupied the minds of many of the prisoners. Escape attempts, via

numerous furtively dug tunnels, met with varying success. In one

foiled attempt, a tunnel was dug at an excruciatingly slow pace

by a prisoner wielding only a small case knife; dirt was dumped

into a cigar box which was drawn out by a string. The tunnel had

reached 30 feet when the escape plot was discovered. In a more-successful

attempt, men from Massachusetts and Indiana managed to complete

a tunnel and head out in small squads bound for points north and

east. However, one of the last men in the tunnel got stuck and,

in a panic, alerted the guards. Due to the early warning, all but

two squads were recaptured.

With the end of the war in May 1865, Camp Ford was

abandoned. Historical records attest to considerable celebration

by POWs and guards alike, and to a large rummage sale in which the

newly-freed prisoners sold what few goods they had to local citizens

in need of utensils, dishes, and various items that had been made

by the prisoners.

In the ensuing years, several prisoners were to return

to Camp Ford to challenge old ghosts and recall lost friends. In

1894, S.A. Swanger visited the old stockade where he had been imprisoned.

Walking over the ground, he found prison relics, the remains of

red clay dugouts, cattle bones, and—in the cemetery area—a

few other bones, perhaps overlooked when the Federal government

disinterred the bodies of 286 Union prisoners after the war. Before

leaving, he took a last drink from the spring and a final look at

the hillside. He wrote later, "Farewell, old spot. And feeling

as if I never wanted to gaze upon it again, I left it…."

|

An artesian spring at Camp Ford furnished

water that, according to one of the prisoners, was cool, crystalline,

and impregnated with iron and sulphur, a combination thought

to make it a good tonic. Although the spring is no longer

there today, a small iron-colored stream runs in the same

creek bed. Evidence of small reservoirs dug by the POW's along

the creek was uncovered by Texas A&M archeologists. Photo

by Steve Black.

|

Examples of some of Camp Ford's better-built

POW housing, as recalled by former prisoner Col. A.J.H. Duganne.

Drawing courtesy of Alston Thoms.

|

|

Soon after their arrival, the POWs began to "arrange

their bivouacs into streets and began to amass green boughs

for wigwams or dark cavernous vaults for troglodytic dwellings,"

according to one prisoner already ensconced at the camp.

|

( (

Camp Ford, shown in a period drawing of

its later years, when houses lined the streets and a market

area was constructed. A central thoroughfare in the camp was

tagged, "Fifth Avenue." Drawing, courtesy of Alston

Thoms.

|

|