A |

|

Adze: Heavy stone tool used for working wood.Most are thought to have been fitted into a socketed wooden handles. Archeologists often refer to these tools as "distally beveled tools" or "gouges" and suspect some of them were used for other purposes (such as hide working). Back to Top |

These are found predominately in Early Archaic sites

along the San Antonio-Guadalupe River drainage and are especially common in Victoria and Goliad Counties.

|

Alluvial: (see Alluvium) |

|

Alluvial Fan: A fan-shaped deposit of sediment that forms where a stream's velocity decreases abruptly or where a stream coming off a sloped incline encounters a less steep surface (like the valley floor) and slows down.During floods, especially flash floods, much of the sediment carried down a hillslope or mountain is deposited where the water slows down and fan-shaped deposits (like deltas) form. Prehistoric farmers in the American Southwest often farmed alluvial fans because of the alluvial sediment and because such places tend to be wetter. Back to Top |

|

Alluvial Terrace: River floodplains formed by flood deposits.Typically, river valleys will have several different terrace surfaces arranged in a stair-step fashion with the oldest terraces being higher and farther from the modern riverbanks than the youngest modern terrace. Back to Top |

|

Alluvium: Sediment (mud, sand, gravel, etc.) deposited by a stream or river.Flood plains and river deltas are two common landforms that are composed of alluvium. Floodplains are often referred to as alluvial terraces. They are called terraces because floodplains are typically flat and level. Through time, as rivers meander back and forth across floodplains and as riverbeds become deeper, they leave behind alluvial terraces of different heights and different ages. In general, the terraces that are highest and furthest away from a river are the oldest whereas the modern floodplain or terrace is the lowest one and the present riverbank. Archeologists pay a lot of attention to floodplains because many sites are located on or within alluvium. Back to Top |

|

Antelope Creek phase: Culture of villagers who lived along the Canadian River valley and surrounding areas in what is today the Texas-Oklahoma panhandle region from about AD 1150 to 1450 or later.The Antelope Creek phase or culture is believed to have developed from indigenous Plains Woodland groups who moved south from the Kansas area, perhaps because of drought. They lived in villages in pithouses and later in pueblo-like rooms whose walls were made out of stacked rock slabs. The Antelope Creek folk built their homes and hamlets close to springs or near the river and cultivated crops—beans, corn, and squash—on a small scale. Nonetheless, hunting and gathering remained an important part of their livelihood. (Alibates exhibit) Back to Top |

|

Archaic Period: (see FAQs) |

|

Arrow points or Arrowheads: Small, light projectile tips attached to arrow shafts and shot with a bow.Often mistakenly called "bird points," tiny arrow points no bigger than your thumbnail were perfectly capable of killing a person or even a buffalo when attached to an arrow shot by an accurate archer. They are small because the arrow shafts to which they were affixed were thin and light, often made of cane. In prehistoric times most arrow points were made of chipped stone, usually chert ("flint"). But along the Texas coast where chert was scarce, arrow points were also fashioned out of seashells. When the Spanish and French brought iron and brass to North America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Native Americans quickly started fashioning arrow points out of metal scraps. By the mid-1800s standardized manufactured iron arrow points were part of the fur trade. Back to Top |

Arrow points from the Graham-Applegate site,

dating to about A.D. 1200. Photo by Milton Bell.

|

Artifacts: Things made or used by people in the past, such as tools, containers, weapons, nails, keys, toys, you name it! Even an animal bone is considered an artifact if it was used or modified by a human. Archeologists can find artifacts lying on the surface or buried in the ground. |

|

Assemblage: (see FAQs) |

|

Association: When artifacts or other objects are found together or close by, they are said to be "associated" or "found in association" with one another.Ideally, physically associated artifacts (i.e., things found together) are also functionally associated, meaning they were used together at more or less the same time. For example, groups of artifacts such as pottery vessels are sometimes found together accompanying a human burial. Such grave goods found together with a single burial represent a single moment in time—the burial of the deceased—an obvious case of close association. In contrast, in many other circumstances it is not clear whether two things found side-by-side were actually left behind at the same time. Most archeological sites do not represent moments in time, but are instead accumulations of things that may have been discarded days, months, or even years apart. A smart archeologist critically evaluates artifact associations and looks for compelling evidence that things found together belong together. Back to Top |

|

Atlatl: Aztec word meaning spear thrower.Atlatls are carved pieces of wood with a hook at one end and a handle at the other. They are used to hurl darts (lightweight throwing spears) and work on the principle of the lever. By extending the reach of the human arm by 18 inches or so, darts can be thrown with considerable force and accuracy. Using atlatl-thrown darts, Aztec warriors were able to penetrate the light Spanish armor worn by Spanish conquistadors under Cortez, killing many. In prehistoric Texas, the atlatl and dart was the main weapon system in use for 10,000 years or more until they were replaced by the bow and arrow between A.D 500-1000. Back to Top |

|

Auger Test: Small probe or test hole dug mainly by power tools.Auger tests are used to determine soil depth, look for buried archeological deposits, and define the limits of a site. Auger holes are typically 2 to 4" inches across and do little or no damage to archeological deposits. Back to Top |

|

Austin phase: Culture of hunters and gatherers in central Texas who lived between about AD 800 and AD 1350. They adopted the bow and arrow and made distinctive corner-notched arrow points called Scallorn points. (Graham-Applegate exhibit)Back to Top |

|

B |

|

Baking pits: (see Earth Ovens) |

|

Biface: Flat, symmetrical, chipped-stone artifact with two sides or faces.The most common method of making chipped-stone projectile points, knives, and many other kinds of tools is to systematically chip away pieces from the edge of a large piece of flint. This creates an elongated or oval-shaped piece of stone that is more or less symmetrical. By continuing to strike off chips, a skilled flintknapper can gradually create a thinner, sharper, and more symmetrical tool, known as a biface. Thick bifaces were used as heavy tools like axes and adzes. Thin bifaces were used as knives or were further shaped and notched to create a dart point or arrow point. Back to Top |

Large, thin bifaces or "knives," although

several may be preforms intended to be further shaped and notched

to create a dart point.

|

Bison: Scientific name for buffalo.The modern American buffalo is Bison bison. This species evolved about 9000-10,000 years ago and is a descendant of larger Ice Age bison of which there were various species. The best known is probably Bison antiquus which was about 15-25% larger than today's buffalo. Back to Top |

The modern bison on the left is considerably

smaller than the Bison antiquus shown on the right. Drawing by Hal

Story, courtesy Texas Memorial Museum.

|

Blade: (1) long, thin, parallel-sided pieces of flint or obsidian (often called prismatic blades) removed from a special blade core; (2) the pointed, triangular part of a dart point or arrow point—everything above the stem.Some collectors refer to the sharp knife-like stone tools archeologists call bifaces as blades, but this adds unneeded confusion given the specialized uses of the term. Blade technology, in the first sense of the word, was only used during two periods in Texas: in Clovis times about 13,000 years ago and then in Late Prehistoric times about 600 years ago. Clovis blades are often very large, whereas most Late Prehistoric blades are much smaller. Both were used as cutting tools or further chipped to make other kinds of tools. Back to Top |

Clovis blades from Gault site, about 13,000 years old. These blades

were used as is as cutting tools or further shaped to create various

other tools. |

Blade Core: A carefully shaped block of flint (chert) from which blades are struck. The classic blade core is wedge shaped with vertical ribbon-like patterns where blades have been removed.Back to Top |

Clovis blade cores from the Gault site, about 13,000 years old. |

Bone-Tempered Pottery: Earthenware pottery made by adding pulverized animal bone to the clay to "temper" the clay and make the pottery stronger.This type of pottery is characteristic of the Toyah culture of central and southern Texas from about AD 1300-1600. Back to Top |

Bone-Tempered Pottery

|

Burned Rock Midden: Low mound of fire-fractured ("burned") rocks and other cooking debris.Burned rock middens accumulated over time from many plant-baking episodes that took place in a baking pit in the center of the midden. These distinctive features are very common (and often called "Indian mounds") in central and southwest Texas. (See What is a Burned Rock Midden?) Back to Top |

Burned Rock Midden |

C |

|

Cache: A group of hidden items found in a tight cluster indicating they were intentionally buried or placed together.Caches are found in campsites and shelters where prehistoric peoples lived, but they are also found in isolated places such as in a crevice or under a boulder. Most of the caches known to archeologists were found quite by accident by farmers, ranchers, and hunters. One cache in east-central Texas was discovered after a storm toppled a large tree, exposing a group of flint knives (bifaces) that had been intentionally buried together long before the tree had been planted. It is assumed that most caches were left behind by someone who intended to return to reclaim the items. Examples of caches include groups of stone tools such as bifaces, piles of stone-tool- making material such as high quality chert (flint), and whole pottery vessels full of shell beads. Caches are particularly valued by archeologists for their scientific importance—such finds can tell us about what prehistoric peoples valued and about how things moved across the landscape. The cache of three painted pebbles shown on the left was found in Bonfire Shelter. Such objects probably were valued because of what the painted designs symbolized. In other words, these probably represent "ceremonial" objects used in rituals such as healing ceremonies. While we will never know their exact meaning, the fact that someone carefully placed these three painted pebbles together in a small hole and covered them up suggests that they were prized. (Painted Pebble Cache) Back to Top |

Painted pebble cache from Bonfire Shelter.

|

Calcined: Term used to describe bone that has been so thoroughly heated that all moisture and grease is oxidized or driven off, leaving only white, easily crumbled pieces.Many of the buffalo bones in the uppermost bone bed in Bonfire Shelter were calcined by the intense blaze that consumed the deposit as the result of spontaneous combustion. (Bonfire exhibit) Back to Top |

|

Chert: Proper name for what most Texans call flint, but both terms are used interchangeably by most people, including Texas Beyond History writers.Technically, the term flint is reserved for fine-grained siliceous stone found in England and France, while very similar, but geologically distinct, siliceous stone in North America is called chert. Most non-geologists do not appreciate this distinction and we don't think it really matters. Call it chert or flint, this hard, fine-grained material was the most important stone used to make chipped-stone tools in prehistoric Texas. This is because it is very hard, yet can be fractured (chipped) in a predictable way. Chert/flint forms in sedimentary rocks, like limestone, over geological time. Since most of Texas once was covered by the ocean, Texas has lots of sedimentary rock and lots of chert. Back to Top

|

|

Colluvium: Loose sediment that accumulates at the base of a hill.Colluvium forms from materials that erode from the top or sides of a hill and fall or are washed by rain down slope. Colluvium is usually loose and made up of a mix of dirt and rocks, depending, of course, on what the hill is made of. Back to Top |

|

Context: "The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs" (Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary). In archeology, an artifact's physical context is exactly where it is found within a site, relative to the site's stratigraphy (layering) and to other artifacts.In archeology, almost everything boils down to "context, context, context." That is to say, the "interrelated conditions" within which an artifact (or site or feature) exists are absolutely crucial to its interpretation. In addition to physical context, we refer to an artifact's behavioral context, meaning the original conditions within which an artifact was used or discarded. Similarly, social context is the nature of the society or group of people that created and used an artifact (or site or feature). While archeologists can directly observe and record an artifact's physical context, the behavioral and social contexts are conditions in the past that no longer exist today. Therefore, these kinds of contexts are inferred based on many different lines of evidence starting with physical context. For example, suppose you find the remains of ancient cooking pit—a circular arrangement of fire-cracked rocks, charcoal, ash, and animal bones including the burned and fractured bones of a deer. Judging from this physical context and the appearance of the bones, you might reason that a deer was cooked at this spot and probably eaten nearby. The cooking and eating are part of the behavioral context—something you can't see but can make an educated guess about. If the cooking pit was found near the mouth of a small cave, you might further reason that the social context was that of a very small group, perhaps members of a single family. You can see how tenuous such inferences are—good archeologists are cautious when trying to reconstruct behavioral and social context. That is why you see us use so many "weasel words"—probably, possibly, maybe, perhaps—absolutely certainty is rare in archeology. Back to Top |

|

Core: Large pieces of stone, usually chert (flint), from which flakes have been removed.Cores are usually the "parent" materials from which chipped-stone tools are made. Sometimes the resulting falkes are used as simple expedient tools, however, more sophisticated stone tools such as bifaces or projectile points can be made from large flakes. Back to Top |

Clovis Blade Cores

|

D |

|

Dart point or dart head: Relatively large chipped stone projectile points used to tip wooden darts hurled with atlatls.Often mistakenly called "arrowheads," dart points are extremely common in many parts of Texas. The stone-tipped darts were propelled with the atlatl or so-called "spear thrower." (Spears are actually handheld thrusting weapons.) The atlatl and dart were used for over 12,000 years in Texas before being replaced by the bow and arrow between about AD 500-800. True arrowheads or arrow points are noticeably smaller and lighter than dart heads. Dart points are fashioned from chert ("flint") and certain other glasslike stones. They are prized by artifact collectors, but valued by archeologists because they are sensitive "time-markers" because, through time, dart point "styles" changed. Some of the differences in shape and size are also related to function. For example, heavy, broad-bladed dart points are often found in association with buffalo bones. Back to Top |

|

Debitage: Stone tool-making debris or waste materials including chips, chunks, and flakes, mainly of flint (chert).Debitage is one of the most artifact common categories. Back to Top |

|

Diatoms: Unicellular microscopic algae with siliceous external shells that can be preserved for thousands of years.Diatoms are very responsive to environmental change and can be used to study long term regional climate change by diatom analysis. Back to Top |

|

E |

|

Earth Ovens: Layered cooking arrangements used to bake plants, especially bulbs and roots, with heated rocks.Earth ovens are often built in scooped-out depressions known as roasting or baking pits. Back to Top |

The dark-stained ring of rocks shown here is the central pit of a small "ring midden,"

a donut-shaped plant baking facility dating to about A.D. 1300.

|

Ecotone: the boundary between ecological zones.Native peoples often lived along ecotones because they had ready access to the resources of several ecological zones. Back to Top |

|

Expedient Flake Tool: Simple stone flakes with sharp edges were used for cutting and scraping.Flake tools are considered "expedient" because flintknappers could quickly make them as needed with little effort and just as quickly discarded them when the task at hand was completed. Back to Top |

|

F |

|

Feature: Distinctive patterns of related things that often represent individual events and that stand out in contrast to their surroundings.Examples of archeological features include hearths, caches, burials, walls, charcoal-stained patches, pits, and postholes. Archeologists pay particular attention to features because they are often very informative. For example, hearths often contain charcoal and broken bone that show what people were eating, provide environmental clues, and can be used for radiocarbon dating. Typically, archeologists keep track of features with special numbering systems, Feature 1 (often abbreviated F1), Feature 2, and so on. On the right is a bell-shaped storage pit feature at the Gilbert site in north-central Texas, probably used to store surplus food for relatively short periods of time. Note how the pit fill is dark and stained by charcoal and/or organic matter. Storage pits were often reused as trash dumps after their original contents were removed. Back to Top |

Bell-shaped underground storage pit at the Gilbert

site—note the distinctive dark pit fill. Photo by Jay Blaine

|

Flake: Stone tool fragment resulting from making chipped-stone tools.Flakes are made by striking the edge of a core or biface. Intact flakes have distinctive "bulbs of percussion" and "platforms." Flakes were sometimes used as expedient tools and were sometimes further shaped into finished tools. Back to Top |

Color, texture, and inclusions were used to sort the

stone debris within the debris piles. Like materials were considered to

be from the same original cobble.

|

Flintknapping: Making chipped stone tools by striking or pressing flakes from chert (flint) cores or bifaces.Tool makers are known as flintknappers or knappers. Back to Top |

Drawing of Flintknapping

|

G |

|

Geoarcheological or Geomorphological investigation: Special studies of the natural deposits of archeological sites and their surroundings.Such studies are carried out by geologists or geoarcheologists and are part of modern archeological investigations because today's "natural" landscape may appear very different from the natural landscape that existed thousands of years ago during the prehistoric era. (see Upper Dry Frio) Back to Top |

Geoarcheological trenching done in 1997 to allow archeologists to better understand the Woodrow Heard site.

|

H |

|

Hearth: An individual campfire or cooking pit often marked by a circular cluster of fire-cracked rocks.Native Americans in Texas (and elsewhere) heated rocks in fires to cook various types of foods. Pavements of heated flat stones could be used as griddles upon which meat and other foods could be grilled. More common are shallow pits with one or more layers of rounded or angular rocks. Many of these are probably the remains of earth ovens or roasting pits, layered arrangements in which heated stones, food, and green packing materials were capped with a final layer of earth to hold in the heat for prolonged periods of time. Archeologists often use the term "hearth" generically to refer to any relatively small cluster of cooking stones or circular patches of burned earth thought to represent individual cooking features. Back to Top |

|

I |

|

J |

|

K |

|

L |

|

Lithic: Pertaining to stone.Archeologists often refer to chipped stone tools and chipping debris as "lithics" and perhaps it does sound better to be called a "lithic expert" than a "stone expert." Back to Top |

|

Lower Pecos: The archeological region in the vicinity of the junctions of the Pecos and Devil's Rivers with the Rio Grande just upstream from Del Rio, Texas.These rivers and their many tributaries form deeply incised canyons within which numerous rockshelters occur. Although the region is arid, averaging less than 15 inches of rain per year, the rivers and temporary waterholes called tinajas within the smaller canyons provided reliable water sources. For over 13,000 years prehistoric hunter-gatherers lived in the region, sometimes occupying the rockshelters. The generally dry conditions coupled with the protected rockshelters resulted in the preservation of fragile materials such as wooden artifacts, woven sandals, and plant food refuse that decay quickly in most other areas of Texas. But the most spectacular archeological phenomenon in the Lower Pecos is the vivid rock art that adorns the protected walls of many of the rockshelters. The red, black, white, and yellow images created by hunter-gatherers in the Lower Pecos beginning at least 5,000 years ago are among the best preserved rock art anywhere in the world. The art and archeology of the Lower Pecos is truly world class, providing archeologists with the opportunity to study the remains of prehistoric hunting and gathering cultures in far greater detail than is possible elsewhere in Texas and in much of the world. (Lower Pecos Canyonlands exhibit) Back to Top |

Spectacular rock art paintings are characteristic

of the Lower Pecos—many are thousands of years old.

|

M |

|

Matrix (plural, matrices): The sediment or enclosing material within which archeological remains are found.Matrices are often distinguished on the basis of differences in color and texture. Matrix samples are often collected from particular contexts, such as a fire pit, so that the contents can be carefully examined later in the laboratory to look for small items such as charred plant fragments or tiny bones that would otherwise escape detection. For an example of a feature with a very distinctive matrix, see the "feature" entry. Back to Top |

|

N |

|

O |

|

Obsidian: Volcanic glass, often black and shiny. (Graham-Applegate exhibit)Back to Top |

Obsidian core and flakes from a volcanic source

in central Mexico.

|

P |

|

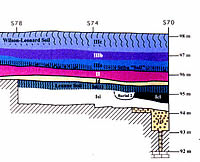

Profile: The side or cross-section view of an archeological site or feature showing its layering (stratigraphy). Profile drawings (also called "cross-sections" or just "sections") often provide critical details that reveal how the layers of a site formed.Archeologists spend a great deal of time studying and drawing profiles. Along with plan maps, profiles are among the most important field documents because they show how different layers, different artifacts, and different cultural zones are situated relative to one another. Typically, archeologists draw profiles on grid paper or Mylar (waterproof thin plastic material). Once they have drawn the major layers, these are numbered or color-coded and described individually. In a complete map, a legend identifies all the symbols and color codes used on the profile. Back to Top |

This drawing shows a profile or section through

Bonfire Shelter.

|

Q |

|

R |

|

Radiocarbon Dating: A method of estimating the age of organic (formerly living) materials younger than 55,000 years based on the amount of radioactive carbon isotope carbon-14 (14C) that remains in them.Since the 1950s, radiocarbon dating has been one of archeology's most important analytical tools. In the late 1940s, Willard Libby developed the radiocarbon dating method, which is based on the idea that all living things incorporate carbon from the atmosphere, and that after death radioactive isotope carbon-14 decays without replenishment, at a known, measurable rate. Radiocarbon has a half-life of about 5730 years, meaning that a 5730-year-old organic object has about half as much carbon-14 as it did when it was alive. Virtually any organic material including bone, plant fibers, and wood charcoal, to name only a few, can be dated. Some materials, however, yield much more reliable dates than others. In many archeological excavations the preferred material to date is charcoal (charred wood or other plant part). In part, this is because charred plants preserve better than uncharred plants, and because there are typically less complexities with dating plants than bone or shell. Using conventional radiocarbon dating methods, it takes about a handful of charcoal to get a reliable date estimate. With the newer AMS (accelerator mass spectrometer) radiocarbon dating method only a tiny sample, the size of a grain of rice or smaller, is necessary. The radiocarbon dating method yields age estimates, rather than definite calendar dates. Radiocarbon ages are a date range expressed in the number of years before the present coupled with an error estimate. For example, the radiocarbon age of one of the charcoal samples analyzed from Bone Bed 2 at Bonfire Shelter is 10,300 +/- 160 BP. The method hinges on the fact that living organisms (like plants and animals) take in atmospheric carbon through metabolic processes like photosynthesis (in plants) and eating (for animals). A tiny portion of atmospheric carbon is radioactive 14C. Upon death, an organism ceases to take in atmospheric carbon and the radioactive 14C slowly begins to decay at a known rate. AMS measures the ratio of stable carbon isotopes to radioactive carbon, and from this measurement scientists can calculate the approximate age of the sample. In contrast, conventional dating methods directly count the rate of decaying radiocarbon. Both methods calculate a radiocarbon age based on that measured quantity of 14C and the radiocarbon half-life. A complicating factor is that the amount of 14C in the atmosphere varied over time due to factors like volcanic activity changing the atmospheric carbon ratio, the industrial revolution adding fossil (ancient, "dead") carbon to the atmosphere, and atomic bomb explosions which cause the creation of extra radiocarbon. Scientists compensate for these atmospheric variations by constructing calibration curves based on radiocarbon dates from known-age materials like tree rings from long-lived species such as the bristlecone pines of California, which can live as long as 3,000 years. Over the years, new and better calibration curves are constructed. Previous radiocarbon ages can be recalibrated using new curves. It is important to remember that radiocarbon dates are estimates of the true age of whatever material is being dated and are presented as a range of possible dates, not one year. Most of the references to radiocarbon dates in this website are calibrated calendar ages unless specified as "radiocarbon years before present" (RCYBP), which is the uncalibrated radiocarbon age. If you want to learn more, see the TBH Special Exhibit Radiocarbon Dating Understood. Back to Top |

|

Rancheria: Spanish word that means temporary village or hamlet. (Graham-Applegate exhibit)Back to Top |

|

Rockshelter: A natural overhang on the side of a rocky slope or cliff that forms a protected shelter.Prehistoric Indians often used rockshelters as temporary living quarters and storage areas. Rockshelters are typically created by long-term geological forces such as water and wind erosion and differ from caves. Caves are relatively deep and often have small openings. Rockshelters are relatively shallow and wider than they are deep. (Lower Pecos exhibit) Back to Top |

Eagle "Cave" near Langtry is actually

a very large rockshelter.

|

S |

|

Site: A distinct place or locality on the landscape where archeological remains are concentrated.Examples of archeological sites include an Indian campground, a rockshelter and a Spanish Colonial mission. The site concept is very important in archeology because the location of a site provides a unique identity. Archeologists carefully document where they find ancient and historic remains; the location of each noticeably separate concentration is marked on a topographic map. Each unique location reported by an archeologist in Texas gets its own site number using the Smithsonian trinomial system. Thus Bonfire Shelter near Langtry has the designation 41VV218; Texas was the 41st state when the system was invented, VV stands for Val Verde County, and Bonfire Shelter was the 218th site in Val Verde County to be officially recorded (today there are over 2,000 recorded sites in Val Verde County). There are official site records for over 54,000 archeological sites in Texas that are maintained at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, the central repository for site records in Texas. Back to Top |

|

Strata: See stratum. |

|

Stratigraphy: The natural and cultural layers that make up an archeological site.Technically, stratigraphy is the actual study of such layers, but archeologists often use the term to refer to the layering of a site as its "stratigraphy." Understanding a site's stratigraphy is crucial to archeologists because the layers (often called "strata") can reveal a great deal about how a site formed over time. In general, younger layers are deposited atop older layers and younger artifacts are found above older artifacts. There are, however, many circumstances in which age reversals and mixing occurs. A simple example is digging a hole through two layers, A and B, and piling the dirt from both layers in one pile on the ground surface. Assume that there are artifacts in both layers and that Layer B formed before the overlying Layer A. If the hole is refilled by randomly scraping the pile of soil back into the hole, the fill layer will now contain a mixture of artifacts of different ages. Suppose the person who dug the hole tossed in an aluminum can before she started filling it back in. This would now be a case of "reverse stratigraphy" because the recent can would be buried beneath a mixed fill layer containing older artifacts. Archeological sites often experience similar sequences of events, making the task of unraveling stratigraphy very challenging. Back to Top |

Stratigraphy |

Stratum: (plural: strata) A distinct natural or human-made layer. For geologists, the textbook example of strata is successive horizontal layers of rock arranged like a layer cake. The strata that archeologists often encounter, however, are rarely so neat and often inclined, irregular, intermixed or otherwise challenging to trace. See glossary entries for "Stratigraphy" and "Profile".Back to Top |

|

T |

|

Topography: The detailed description or depiction of the physical features of the surface of the earth. Topographic maps usually show contour lines of equal elevation relative to sea level or an arbitrary reference point.Archeologists depend on several kinds of topographic maps. For locating sites, the fine maps produced by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) are usually used, especially the 7.5' topographic quadrangles, which cover 7.5 minutes of latitude by 7.5 minutes of longitude: east-west dimensions are 7 miles (11.3 km) in north Texas, 7.8 miles (12.6 km) in south Texas; north-south dimensions are 8.67 miles (14 km) for all parts of the state. USGS 7.5' maps are available for the entire state of Texas and most of the U S through the U S Geological Survey and the Texas Natural Resources Information System. To show the finer topographic details of an archeological site, archeologists often create their own topographic maps using surveying equipment. Today many archeologists use a computerized electronic survey tool known as a total data station (TDS) to create maps. Earlier generations of archeologists relied on optical surveying equipment including transits and the plane table and alidade. The latter is a particularly effective tool because it allows archeologists to draw what they are mapping as they go along. With transit readings or a TDS, the map is drawn back in the laboratory and sometimes suffers from missing details. Ideally, one combines the measured distances and elevations with firsthand observations to create a map that accurately and completely conveys what the archeological site looks like. Back to Top |

An example of a highly detailed topographic map

in-the-making of an archeological site in a valley. Each of the

dots on this raw map represents the location of an elevation shot

taken by a total data station. The final published map will be cleaned

up and simplified. Map created by Ken Brown.

|

U |

|

V |

|

W |

|

X-Z |

|

Texas Beyond History

>

Texas Beyond History

Site Map

TBH WebTeam

15 May 2006