|

In this section:

|

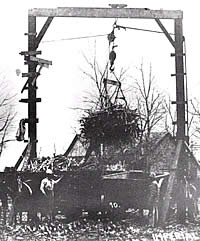

Harvesting and loading sugar at Masterson

Plantation. Photograph courtesy of the Brazoria County

Historical Museum.

|

|

The alluvial soils of this Gulf Coast Plain were

a source of great wealth for the sugar planters.

|

Map of Brazoria County, with locations

of four early sugar plantations, including Lake Jackson.

|

Loading sugar cane into wagons at

Sugarland, Brazoria County. Date unknown. Photograph

courtesy of Brazoria County Historical Museum.

|

Indian Church sugar mill in Belize.

The cane crushers are still in place along with the

flywheel and engine that powered the mill. Photo courtesy

of Don McCormick.

|

Sugar mill excavations looking west.

The large ruin in the background is part of the original

Jackson period cane crusher foundation. The bricks in

the foreground are part of the convict period boiler

foundations.

|

On the right is the base of the foundation

for the cane crushers. On the left are two fragments

of the gears that turned the crushers. In the center

are the bands that held together the horse-powered treadmill.

|

Fragments of the copper sieve that

was placed just below the cane crushers. The sieve prevented

fragments of the cane plant from getting into and contaminating

the cane juice.

|

A train of kettles from an 1857 drawing

by Henry Olcott. Of the five iron kettles, the largest

was La Grande (shown in this drawing as a vat) and the

smallest was La Batterie. The fire was under La Batterie;

the heat from the fire was drawn under the other kettles

and then up the flue chimney. The kettles were completely

enclosed by a brick foundation and plastered to contain

the heat.

|

Plan of the Jackson period sugar

mill and convict mill, drawn after excavations were

completed. Archeologists noted differences over time,

including changes in the area of the kettles. The arrangement

of kettles was the same but the flue chimney was completely

sealed off in the convict mill. The convict period added

a foundation for the new boilers to heat the kettles

and raised the floors.

|

An example of convict construction

at Lake Jackson, showing the poor quality masonry work.

Note the sagging line of bricks in the foundation.

|

This photo shows how the flue chimney

was blocked by a convict wall. The large metal bar

is identical to the bars in the firebox at the Osceola

Mill. It has been "tossed" because it was

no longer needed.

|

In the lower part of this photo,

the lime well from the Jackson period and the Jackson

floor are visible. To the right is a doorway between

the mill proper and the purgery that was sealed during

the convict period. Convicts built the wall in the center

on top of the Jackson wall; metal bars were used to

stabilize the addition. The original kettle settings

had to be torn apart to place steam coils around the

kettles when the "steam train" method for

heating the kettles was implemented. The firebox was

removed, and the flue chimney blocked by a wall.

|

|

The Lake Jackson mill may be the only mill in Texas

with preserved evidence of the steam train technology

available for archeological study.

|

|

The first refineries in Texas were sugar mills

that turned the juice of sugar cane into granulated sugar.

Sugar cane is not native to the Americas. Its origin lies

in Southeast Asia. Christopher Columbus brought sugar cane

to the island of Santo Domingo on his second voyage, and from

there it spread to North, Central, and South America.

When Moses Austin visited the Spanish Governor

in San Antonio, Texas, in 1820, he expressed his hope of bringing

300 families to Texas to raise cotton and sugar. The Governor

knew that sugar cane would grow in Texas—a small sugar

mill already had been established at Mission San Jose y San

Miguel de Aguayo in San Antonio sometime before 1755. Although

Moses Austin received his impresario grant, he died soon after

his return to Missouri, leaving his son, Stephen, to assume

his father's mission. Stephen F. Austin traveled to Texas

to choose the best land to raise sugar cane: the land near

the Brazos and Colorado Rivers. The alluvial soils of this

Gulf Coast Plain were a source of great wealth for the sugar

planters. The Brazos and San Bernard rivers, Oyster Creek,

and numerous meandering bayous, provided transportation.

By 1828, the first sugar mill in Austin's Colony

had been established and by 1850, there were 45 large plantations

producing millions of pounds of sugar a year. African-American

slaves provided most of the labor. The Civil War devastated

the sugar economy in Texas. After the war, Texas planters

began to revive the sugar industry using convict labor. The

Imperial Sugar Company began with the 1875 partnership of

Edward H. Cunningham and Colonel Littleberry A. Ellis. To

operate their sugar lands, they leased the entire Texas prison

population and sublet those laborers they did not need. In

the 1890s, Colonel Cunningham built a mill and installed the

machinery needed to refine sugar. In 1905, it became Cunningham

Sugar Company and in 1917, the Imperial Sugar Company.

Sugar production in Texas peaked in the 1880s

and declined afterwards as the trend toward consolidation

of sugar mills developed. The industry took a bigger blow

in 1910 when a new law prohibited the leasing of any convicts;

thus the sugar mills lost the majority of their work force.

Sugar cane is no longer grown commercially along the upper

Texas Gulf coast. Nonetheless, the Imperial Sugar Company

in Sugar Land, Texas still refines sugar imported from Hawaii,

Louisiana, and Puerto Rico.

From Stalk to Sugar: The Sugar-Making Process

Sugar was made in nineteenth-century Texas mills

by a very involved and complex process. The first stage—extraction—entailed

squeezing the juice from ripe sugar cane with steam-powered

crushers. The juice was pulled by gravity from upstairs crushers

to the first floor vats. The earliest mills in Texas used

horsepower to drive wooden rollers to extract the cane juice.

In 1843, the first steam-powered mill was established on Captain

William Duncan's Caney Creek plantation.

The second phase of sugar production was the

reduction process which requires a fire, a train of progressively

larger kettles, and the flue chimney. Heat was produced by

a fire under the smallest of the kettles (usually about 6

feet in diameter). The heat was then pulled by the height

of the chimney through the flue under the kettles to where

it exited up the tall chimney. The molten sugar scum was repeatedly

skimmed from the top of each vat as the liquid was passed

on down to the smallest kettle.

The final phase of the sugar process was granulation,

cooling, and purging, which took place in the purgery—a

large space attached to the reduction room to hold cooling

trays and vats. When the syrup in the smallest and hottest

kettle began to crystallize, it was removed into cooling trays.

Cooling trays were usually wooden troughs about 10 feet long,

5 feet wide, and 10-12 inches deep. After about 30 days, the

uncrystallized syrup,or molasses, was drained into a molasses

barrel leaving behind crystallized sugar.

Investigating Historic Mills

With knowledge of the sugar-making process,

archeological investigators formulated specific research questions

prior to beginning excavations at Lake Jackson.

- What was the layout of the original Lake

Jackson mill? Was it similar to or different from other

sugar mills in Texas?

- How was the mill changed when steam power

was added? The historic record documents the addition of

steam power to operate the cane crushers. Where were the

boiler, boiler chimney and engines located?

- How was the mill altered after the Civil

War when steam replaced fire as the source of heat in the

reduction process?

Prior to excavating the Lake Jackson mill, three

historic Texas sugar mills—Bynum, Osceoloa, and Varner-Hogg—were

mapped to distinguish similarities and differences. Although

all are in ruin, the remains are substantial enough to identify

the main components.

Osceola Mill is the best-preserved mill and

made identification of the shared attributes of the other

mills possible. It was determined that all three are long

and narrow and have cisterns close to them. They all have

the flue chimney outside the structure and they are all divided

into two parts, the crushing area and the purgery. At Osceola

and Bynum, the boiler chimneys could be identified; both are

outside the sugar mill.

Tracing the Sugar Making Process at Lake

Jackson

To recap, the three processes in making sugar

are, extraction, reduction, and crystallization. The extraction

process extracts the juice from the sugar cane. This process

is done with large iron crushers that were powered by a horse-powered

treadmill attached to the crushers or by a steam boiler which

provided steam power to turn the cane crushers.

The historical records state that Jackson began

the mill using horsepower to run the cane crushers that extracted

the juice from the cane. The tallest part of the mill ruins

was the foundation for the massive cane crushers placed on

the second flour. As investigations got underway on the brick

floor next to the cane crusher foundation, excavators uncovered

horse harnesses and large metal bands.

Although records indicate that Jackson installed

a boiler to steam power the cane crushers, neither the boiler

nor the boiler chimney were found during extensive excavations.

All evidence indicates that the horse-powered treadmill was

still in place when the mill was destroyed by the 1900 hurricane.

The second phase of sugar making is the reduction

process that boils the cane juice until the juice crystallizes

into granulated sugar. In the original Jackson mill, sugar

cane juice was reduced to a granular form in a "train

of kettles," a series of large to small kettles heated

by a fire under the smallest kettle. The heat from the fire

was pulled through the flue, under the series of kettles,

by the draft of a flue chimney. Excavators identified the

opening of the flue chimney and the flue chimney foundation

at the Lake Jackson mill, along with the circular brick remains

of the kettle settings.

When the sugar began to crystallize in the smallest,

hottest kettle, the thick syrup was removed to cooling trays

where the crystallization process continued. When the

sugar cooled, it was placed in hogsheads, storage barrels,

where the remaining molasses, uncrystallized syrup, was allowed

to drain out of the hogsheads. The room where this separation

occurred was called the purgery. Each hogshead contained about

a thousand pounds of sugar. About three barrels of molasses

were drained from each hogshead. The molasses was shipped

to the Caribbean to be made into rum.

Post Civil-War Sugar Production

An inventory of property at Lake Jackson Plantation

in 1878 documents the change from fire to heat the sugar kettles

to the use of steam as a heat source. By this time, the Jackson

family no longer owned the plantation. The new owners completely

converted the mill to adapt to steam power to heat the kettles.

The kettles were stripped of their foundations, steam coils

were wrapped abound the kettles to provide a more regulated

heat and the kettle foundations were rebuilt.

In addition to the changes in sugar making technology,

a major change was made in the labor force at the mill: convicts

replaced the slaves. After the Civil War, the state of Texas

rented out their convicts as a labor supply.

Differences in workmanship between the Jackson

period construction and convict labor period became increasingly

apparent during excavations. During the Jackson period, bricks

made by the slaves were uniform in size, clay was high quality,

and firing was regular. Only whole bricks were used, and walls

were constructed with exceptional craftsmanship. In contrast,

convicts were poor masons and used low-quality materials.

They used bricks of different sizes, including fragmentary

pieces, in their construction and applied mortar irregularly.

Walls and foundations tended to slope and buckle over time.

Other evidence helped archeologists distinguish construction

of the two periods. For example, alterations made by convict

labor after 1873 include:

Blocked Passageways: A blocked doorway

was found in the wall separating the kettle area from the

purgery. The east side of the wall shows an enclosed portal

with plastered walls, while the west side has very sloppy,

and uneven rows of bricks with "bleeding" mortar.

The door between the crusher foundations and the kettle area

was also closed with a brick wall.

Raised Walls: The east/west wall, the

south wall of the Jackson kettle enclosure, is an excellent

example of a raised wall. Attached to the Jackson wall, iron

masonry braces were placed about every four or five feet and

a new section of wall was added. This alteration may be a

result of the change from fire heat (train of kettles) to

steam heat (steam train). The upper portion of the train of

kettles would have been removed to expose the sides of the

kettles. After steam coils were wrapped around the kettles,

then the kettle area would have been sealed to enclose the

kettles and contain the heat. This would explain convict walls

on top of plantation walls in the kettle area.

Raised Floors: The lower Jackson floor

is like the Jackson foundation and walls in construction;

substantial, level, and with excellent masonry. The lime pit

and original Jackson floor found in 1994 became the cornerstone

for all other Jackson floor identifications. The upper or

raised convict floors are uneven. When the floor is of brick,

it is one brick thick and of poor masonry construction. Convict

period floors are also of dirt and had between 1 - 1.25 feet

of fill between the Jackson floor and the convict floor.

Blocked Chimney: The flue chimney opening

was closed by bricks and was separated from the kettle area

by a brick wall during the Convict Period alterations.

Firebox removed: The brick foundation

and grates of the firebox were removed and the opening to

the firebox on the north wall was closed with a brick wall.

In 1995, more of the original Jackson plantation floor was

uncovered along with a kettle setting and a heat flue in the

middle of the sugar mill. Since 1995, the other original kettle

settings have been located and the boiler and engine platforms

of the Convict period have been identified.

Putting the Pieces Together

Excavations revealed the components of the original

Jackson mill: the horse treadmill that supplied the original

power; the foundation for the cane crushers; the original

train of kettles with fire box, kettle settings and flue chimney;

and the purgery and storage area. By comparing the Lake Jackson

mill to Osceola, Varner-Hogg and Bynum, it was learned that

these four mills in Brazoria County were very similar in design

and layout—reflecting a shared process. Historic records

state that the mills at Retrieve and Darrington—Jackson's

other plantations—had double rows of kettles, called

a double train. These two plantations are now state prisons.

Although historic records document the addition

of steam power to operate the cane crushers, the boiler and

boiler chimney were not located during excavations. The foundation

for the cane crushers probably remained the same. The change

was from wooden to metal rollers to crush the cane. The heavier

weight of the metal rollers may have required a more substantial

foundation and the original foundation may have been augmented.

After the Civil War, the mill was significantly

altered in the transition to the "steam train" method.

The cane crushing area is the only portion of the mill that

not altered by the change. Addtionally, in the area between

the large foundations of the crushers and the kettle area,

the floor was raised with rubble about 1.5 feet above the

Jackson floor. A single brick thick floor was laid on the

rubble that contained a hole and drain. The train of kettles

was torn apart, the firebox was removed, and the top portion

of the kettle supports was removed to expose the kettles.

The kettles were wrapped with steam coils of metal that were

connected to the newly installed boilers. The kettle supports

were then rebuilt resulting in convict construction on top

of Jackson construction. Metal rods supported the new construction.

The area around the open kettles would have been sealed to

keep heat from escaping from below the kettles.

Since fire was no longer a source of heat, the

flue chimney was bricked closed and a wall built separating

the chimney from the mill; the area became a trash dump. A

new foundation for the new boilers was constructed north of

the mill, close to the location of the kettles.

What was the purpose in changing to steam heat?

According to George Olcott, who studied the sugar making process

during the mid-nineteenth century, "Steam does not discolor

the sugar nearly so much as fire, therefore steam trains have

been extensively adopted, and great expense has frequently

been incurred in altering the arrangement of the boiling-house

to suit the new regime. A steam train will cost twice

as much to run and keep in order as a common train will, to

say nothing of the first expense…" Many mill operators

claimed the heating of the kettles was easier to control but

workers had to be highly trained to make the process work.

Because so many Texas sugar mills have been

completely destroyed or are in ruins, and because the historical

record is incomplete, we do not know how many sugar mills

changed to the steam train method. The Lake Jackson mill may

be the only mill in Texas with preserved evidenced of this

technology.

|

Stephen F. Austin followed through

on the dream of his father, Moses Austin, to establish

colonies in Texas and raise cotton and sugar. Image

courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives.

Click images to enlarge

|

Major plantations in Brazoria County,

Texas. The success of sugar cane planters such as Abner

Jackson earned Brazoria, Fort Bend, Wharton, and Matagorda

counties the title of "sugar bowl" of Texas.

The location of two of Jackson's three plantations are

denoted by the letter "N."

|

|

Sugar cane plants at various stages

of growth. Photos courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife

Department and the Cooperative Extension Service, Texas

A&M University.

|

Map of ruins of four nineteenth-century

sugar mills in Texas, surveyed to provide comparative

information on size and layout.

|

Volunteers at Lake Jackson Plantation

taking a reading with transit. Photo by Mott Davis.

|

Western end of sugar mill before

excavation. The foundation of the cane crusher is in

the center. The tallest feature is the support for the

cane crusher.

|

When the bands were completely exposed,

the size of the treadmill could be determined by the

circumference of the bands. The green copper sheeting

fragments are part of the copper sieve under the cane

crusher.

|

Below the bands and the sieve, excavators

found the treadmill bars and remnants of horse harnesses.

The bars were the treadmill for the horses, or mules,

and the harnesses held the animals in place.

|

The settings for the five kettles

can be seen with the smallest kettle—which was

directly over the firebox—at the top of the series.

All of the kettles were sealed in brick and plastered

so the heat could not escape. The heat was pulled from

the firebox through the train of kettles by the height

of the flue chimney. The heat passed under all of the

kettles and out the flue chimney.

|

|

Steam does not discolor the sugar nearly so much

as fire, therefore steam trains have been extensively

adopted, and great expense has frequently been incurred

in altering the arrangement of the boiling house to

suit the new regime. —George Olcott.

|

Convict period boiler and engine

foundations in the mill. In the foreground is a pipe

draining from the convict-period boilers into Lake Jackson.

In the center are the metal plates on the brick foundation

to support the boilers of the "steam train."

|

Excavators work to uncover another

area of the sugar mill. Structure I can be seen in the

background.

|

|