At its zenith some 500 to 600 years ago, Pine Tree Mound was an important, thriving community within the Nadaco Caddo world.

The nucleus of this community apparently consisted of about 15 household compounds situated around the ceremonial precinct, which had its complement of ceremonial buildings and houses for the group’s leaders and priests.

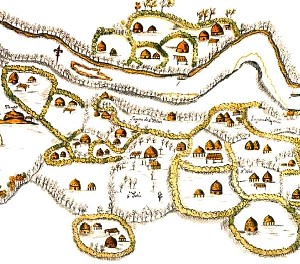

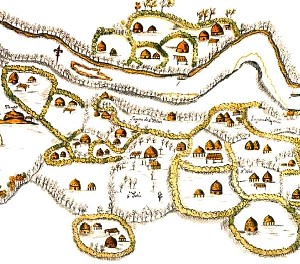

If archeologists are correct in this estimation, then it appears likely that up to about 125 people lived here at any one time. In general, this village looks much like what is shown on a map of a Nasoni Caddo village on the Red River that was made when Domingo Terán de los Ríos, the first governor of the Spanish province of Texas, visited there in 1691.

Some of these residential areas were close to the ceremonial precinct, while others were much farther away. This variability in distance appears to be a functional rather than formal distinction. In other words, places on the landscape best suited for building houses were chosen, as opposed to a planned layout of villages arrayed around the ceremonial area. Other considerations may have come into play, however. For example, it is possible that higher-status members of the community were allowed to live closer to the ceremonial area than commoners.

So, what did these household compounds look like? Based on the excavations in three of them, it seems that, more often than not, each consisted of a single circular pole-and-thatch house averaging about 20 feet (6 m) in diameter. Two houses may have stood simultaneously in some areas at certain times, but this appears to have been the exception rather than the rule. Auxiliary structures such as ramadas covering outdoor work areas and granaries for storing corn probably were present as well, along with less-substantial structures such as drying racks and wind screens.

The evidence from the excavations suggests that the Caddo did not occupy most of these residential areas continuously. They built a house and then rebuilt it once, twice, or three times as deterioration occurred and support posts needed to be replaced. Each use spanned perhaps no more than 40 years; then they abandoned that area for a time before reoccupying it again later and building a new house. Thus, these can be seen as multigenerational house compounds. What spurred the ebb and flow of occupation is unknown, although it could relate to events such as the death of a lineage head, for example.

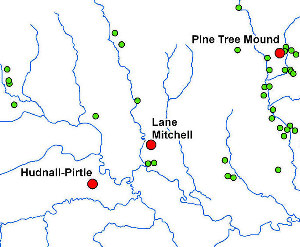

This community extended beyond the Pine Tree Mound site, however, and archeologists have been able to approximate the extent of the greater Nadaco "neighborhood." Because of extensive lignite mining in this part of Harrison County, archeologists have walked over many thousands of acres and found about 400 archeological sites with Native American artifacts. Forty of these sites distributed along four northern tributaries of the Sabine River and the margin of the river valley itself appear to be the same age as Pine Tree Mound, and thus the people who lived and camped at these places probably were connected to the people who lived at Pine Tree. Three of the tributary valleys—those of Spring, Hatley, and Clarks Creeks—each have just a handful of sites. The fourth—Potters Creek—has the most sites, including Pine Tree Mound, and this cluster of sites appears to represent the main Nadaco Caddo village, with Pine Tree Mound as its political, social, and religious anchor. This main village stretched for a distance of about 3 miles up and down the creek.

How Big Was the Territory of the Nadaco Caddo?

Clearly, the powerful leaders who lived at the Pine Tree Mound site ruled an area larger than just the Potters Creek valley and those of nearby tributaries. Because of uneven archeological coverage, it is hard to judge just how large their territory was, but there is enough evidence for archeologists to hypothesize that the greater Nadaco Caddo territory extended across an area roughly 30 miles (50 km) north-south by about 40 miles (60 km) east-west, with the Sabine River and its broad floodplain running through the middle. People were not distributed evenly throughout this area, though. As noted, the main village was north of the river, stretching for 3 miles along Potters Creek and anchored by the Pine Tree Mound site at its north end. The rest of the community appears to have been more rural, with widely scattered household compounds in other north-side tributary valleys and the entire territory south of the river, accounting for well over half of it, having been sparsely settled. The Nadaco Caddo undoubtedly hunted and fished on the Sabine River floodplain, but this area floods too often for it to have been a good place to build houses.

The Nadaco Caddo and the Southern Caddo World

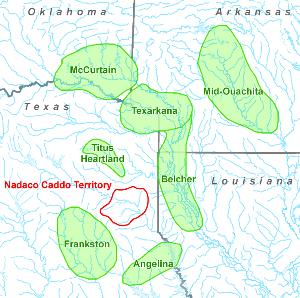

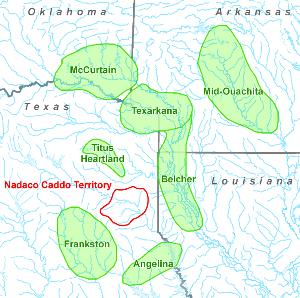

The Nadaco Caddo did not live in isolation from the wider Caddo world. The deepest connections were with Caddo groups living in the Cypress Creek drainage just to the north and northwest. These groups belonged to what archeologists have labeled the Titus phase. (A phase refers to a pattern of archeological remains—a cultural expression—relating to a particular time period and area.) There also was interaction with Belcher phase groups who lived along the Red River to the east and northeast, Frankston phase peoples in the upper Neches/Angelina basin to the southwest, perhaps the Texarkana and McCurtain phase Caddo who lived on the Red River at and above the Great Bend to the north, and likely even Mid-Ouachita phase groups in south-central Arkansas.

Clues about these connections come from the kinds of stones that some of the tools and ornaments from the Pine Tree Mound site are made of. The vast majority are of materials that could have been obtained locally, but small numbers came from the Ouachita Mountains of Oklahoma and Arkansas or gravels redeposited in the Red River from the Ouachitas. Given the source areas, these nonlocal rocks may indicate interaction with McCurtain, Texarkana, and even Mid-Ouachita phase peoples.

Particularly notable are three sets of stone ear spools recovered from three graves. These are similar in form and size to two sets of ear spools from the Belcher phase Foster site in southwestern Arkansas, and the craftsmen who made these items may have been residents of that region and obtained the argillite they are made of there. Least prominent in the collection are artifacts of materials that appear to be from central Texas and the southern part of east Texas; these probably were introduced through contact with Frankston phase peoples. The overall infrequency of these tools and ornaments, and the fact that many were included as grave offerings, indicate they were not mundane items. Instead, most were prized symbols of power, authority, status, or role, as well as symbols of the connections that tied elite members of the Pine Tree Mound community to their peers in neighboring and more far-flung Caddo communities, cementing relationships between them.

The pottery found in the graves provides other important clues about connections. A few of the pots from Pine Tree Mound clearly are imports from Belcher, Texarkana, and Frankston phase peoples, but the vast majority were made locally or by potters living in Titus phase sites to the north or northwest. In fact, the strong connection through a shared ceramic tradition between the Pine Tree Mound site and Titus phase communities indicates these groups were closely related.

We do not know what the people who created the Titus sites called themselves, since the accounts by the early explorers and traders who visited that area did not record that information. There is one important piece of evidence indicating that the Nadaco Caddo at Pine Tree Mound considered themselves separate from their neighbors in the Titus phase heartland, though. That evidence comes from how they buried their dead. At Pine Tree, the Nadaco Caddo buried people with their heads to the south or southeast, while the Titus phase Caddo oriented graves to the east and northeast.

These different burial practices may be one way that groups within associated communities differentiated themselves while still participating within the wider Caddo society. In this case, it appears that the path of souls mythology may have had a role in the practices for both. The Titus phase Caddo generally buried their dead with their feet on the path of souls and their heads to the rising sun. Those buried at Pine Tree Mound also had their feet on the path of souls, but their heads would have been aligned with the Great Serpent as represented by Antares, with the rising sun on their right hand.

What Happened to the Nadaco Caddo People?

People continued living at the Pine Tree Mound site into the 1600s and 1700s, but the heyday of that place as both a population center and the focus of ceremonial activities for the community was in the 1400s and 1500s. Why did this change, and what happened to the people who made up this community? Population loss from diseases introduced by the 1542 visit by the De Soto expedition could be part of the answer, but events that unfolded over the succeeding two-and-a-half centuries also must have played a role. Sitting so close to the Hasinai Trace, the Caddo of the Potters Creek valley were in a prime location to meet and be affected by the European and American explorers, traders, and later settlers who frequented the area starting in the 1680s, as well as immigrant Native Americans from the southeastern U.S. Their interactions with many different groups brought about a slow decline, dispersal, and reconfiguration of the population. A map made in 1717 indicates that one branch of the Nadaco Caddo had moved south into the Angelina River basin to be near the Hasinai Caddo by that time, but Pedro Vial’s account is clear that a northern branch was still living in the Sabine basin in 1788.

There are a number of sites in and around Harrison County where graves containing Caddo pottery and historic trade materials have been found, and two of these, Susie Slade and Henry Brown No. 1, are in the Potters Creek valley just south of Pine Tree Mound. The kinds of trade goods—including glass beads, gun parts, hawk bells, and iron arrow points or knife blades—indicate that at least parts of these cemeteries were created in the 1700s and probably early 1800s. Whether these sites represent parts of the reconfigured Nadaco Caddo community formerly centered at Pine Tree Mound or settlements by new intrusive groups remains an open question. The fact that some of them are close to Pine Tree argues for the first interpretation, as does the fact that some burials are oriented the same way as the burials at Pine Tree.

But most of the pottery from these later sites looks more like pottery made by Caddo groups who lived on the Red River to the east and north. For instance, these graves contained pots in styles that archeologists call Natchitoches or Hodges Engraved, Simms or Darco Engraved, and Emory Punctated, unlike the graves at Pine Tree Mound where Ripley Engraved bowls and bottles and Pease Brushed-Incised jars were common. This suggests that the later pottery did not develop out of the ceramics made in the Potters Creek valley; instead, its antecedents appear to lie elsewhere. These styles of pots do occur over a wide area, however, and they may have been acquired through trade rather than the movement of people.

One way of interpreting the evidence from the Potters Creek valley is that it does contain the remnant resident population of the Pine Tree Mound community, but one that had been affected in profound ways by interactions they and other Caddo groups had with Europeans and Americans between the late 1600s and early 1800s. With so many changes afoot, and so much movement of people and interaction between groups, both Native and not, it is little wonder we see differences from what was common just a short time before. What remained of the Pine Tree Mound community probably had been severely altered by population loss through disease and rapid shifts of the centers of political power as Europeans and Americans entered the region. Other Caddo groups likely consolidated with or subsumed what was left of this community in the face of these changes, creating an archeological signature different than the one that preceded it. |

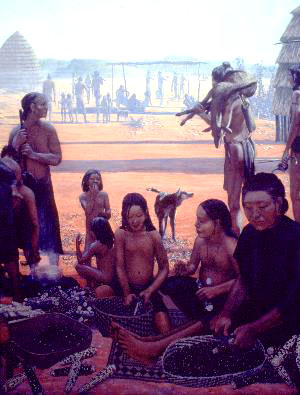

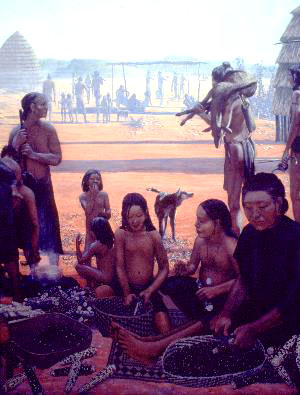

Artist’s reconstruction of a Caddo village scene. Painting by Nola Davis, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Map of a Nasoni Caddo village on the Red River, from Domingo Terán de los Ríos' 1691-1692 expedition through what is today east Texas. The map, drawn by an unknown member of the expedition, is the earliest known cartographic depiction of a Native American community in Texas. Original map in the Archivo General de Indias, Seville.  |

THE LANE MITCHELL SITE

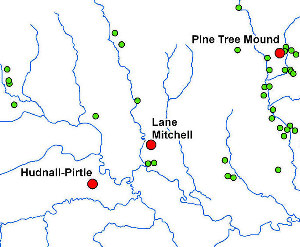

Map of the north side of the Sabine River valley near the Pine Tree Mound site showing known archeological sites likely associated with it.

Of the forty known sites near Pine Tree Mound that appear to be the same age, all but one likely represent small household compounds where one or two families lived, or maybe places where people camped while on hunting trips or tending agricultural fields. The one site that is different, called the Lane Mitchell site, is southwest of Pine Tree Mound. It is marked by four or five small mounds lined up along the bluff overlooking the creek valley. Limited excavations suggest that most or all of the mounds contain burned structures probably used in religious ceremonies and possibly similar to one or both of the two smaller mounds at Pine Tree Mound. Unlike at Pine Tree, though, there is neither an obvious plaza nor surrounding village compounds.

Just how Pine Tree Mound and Lane Mitchell are related is unknown, but the latter is probably a secondary ceremonial space. The fact that Lane Mitchell sits astride a straight northeast-southwest line between Pine Tree and an earlier Caddo mound center known as the Hudnall-Pirtle site has led archeologists to speculate that it may have served as a geographic marker connecting the old center of power and authority (Hudnall-Pirtle) with the new (Pine Tree Mound).

|

The Nadaco Caddo territory in relation to other contemporaneous Caddo archeological phases.  |

This set of ear spools found in a burial at the Pine Tree Mound site provides clear evidence of contact with other Caddo groups. The ornaments were expertly fashioned, possibly on a lathe, from a porcelaneous sedimentary rock called argillite. Their form and method of manufacture suggest they originated in southwestern Arkansas, indicating that the Pine Tree Mound people had wide-ranging contacts in the Caddo world.

|

TWO DIFFERENT POTTERY STYLES

The bottle at left, from Pine Tree Mound, is a markedly different style than the bottle at right, recovered from a later Caddo grave in the area. Enlarge for additional examples.

The graves at Pine Tree Mound contained many bottles and bowls in a style called Ripley Engraved. Excavated Historic Caddo graves in the area yielded few vessels of this style. Instead, they had ones with different shapes and decorations in styles known as Natchitoches and Simms Engraved. This change in the ceramics signals a disruption in local pottery manufacture that relates to an influx of new peoples into the region in the 1700–1800s, new ideas about how to make pottery, or both. |

ARROW POINTS TO GUNFLINTS

Arrow points and gunflints found at Pine Tree Mound.  |

|