|

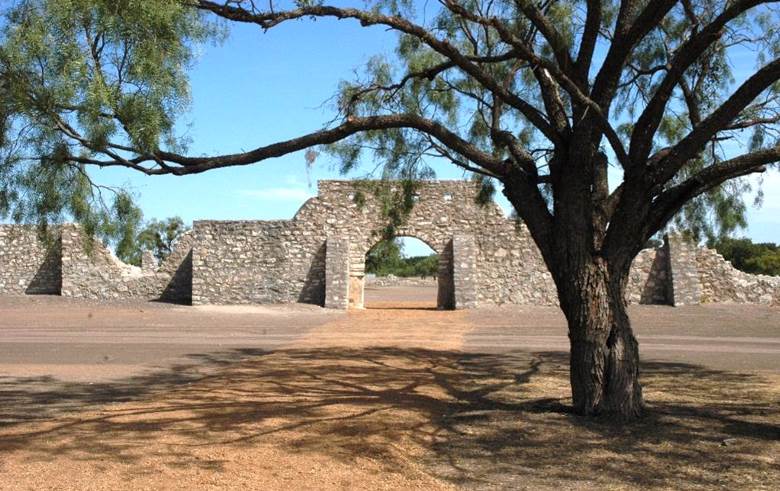

The story of Presidio San Sabá is the story of Texas. It is the story of contentions and competing interests. It is the story of the Spanish Colonial pursuits of God, glory, and gold, and of the struggle of Native American groups to thwart the foreign invaders. Today the presidio (Spanish for "fort") lies in ruins, but it is not hard to imagine how it looked at its height in the mid-1700s, when it was home to more than 300 Spanish soldiers and civilians, some of them women and children. You can picture the soldiers practicing drills in the presidio's open courtyard while herders tended cattle and farmers worked the nearby fields. With imagination, you might catch a whiff of fresh-baked bread and meat roasting on a spit or hear children playing in the courtyard. But then, suddenly, the reverie ends with the shout "Fore!" followed by the sharp thwack of a metal club striking its target, and then the quiet thud of a golf ball finding purchase on the green. Today, Presidio San Sabá lies just outside the town of Menard, Texas, at the western edge of the Texas Hill Country. The presidio sits amid Menard's Municipal Golf Course, not far from the clear, winding San Saba River. The standing stone ruins are evocative, but they are not from the original 1760 stone construction. Instead, they are the remnants of a past project to reconstruct the presidio. In 1936 and 1937, a crew hired by the Texas Centennial Commission and paid for by a grant from the Texas Legislature reconstructed the northwest portion of Presidio San Sabá as a tangible reminder of the past. These reconstruction efforts, relatively faithful to the design of the original presidio, began to deteriorate not long after their completion. Today they are just a ruin, another crumbling testament to Texas history. Presidio San Sabá, originally known as Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas, was constructed in April of 1757 by a Spanish force led by Captain Don Diego Ortiz Parilla. The presidio, which was subsidized by the Spanish crown, had a threefold purpose: to protect the nearby Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá, to assess the validity of rumors of rich silver deposits in the area, and to guard the Spanish frontier against the threat of Indian encroachment. The companion Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá was built a few miles downstream for the purpose of Christianizing the Lipan Apache. But by soliciting the Apache, the Spanish unwittingly made enemies of the Norteños, long-time foes of the Apache. The Indian groups the Spanish called Norteños ("northerners") included various bands of the Comanche, Wichita, Kitsai, and Caddo tribes who were united in their hatred of the Apache. The Nortenos were also trading partners and sometimes competitors whose territories covered a huge swath of the Southern Plains and into the forests of East Texas. In March of 1758 a large force of Nortenos attacked, looted, and burned Mission San Sabá, less than one year after its founding (see the Texas Beyond History exhibit on Mission San Sabá). The mission was never rebuilt, however, the presidio lived on for another 14 years until hope for silver riches waned. The presidio was abandoned in 1772 by order of the Viceroy of New Spain. Although the location of the mission was "lost" for a number of years, the presidio site has always been obvious. Archeological survey and testing was done there in 1967 by noted Spanish Colonial archeologist Kathleen Gilmore, working for the Texas State Building Commission, and again in 1981 by James Ivey of the University of Texas at San Antonio. In June of 2000, students of the Texas Tech University Archaeological Field School, under the direction of Professor of Anthropology Dr. Grant Hall, began the first formal excavations of the site. Texas Tech has returned to Presidio San Sabá for the 2001 and 2002 field seasons, under the direction of Hall and Dr. Tamra Walter, also a Texas Tech anthropology professor. Texas Tech will continue its investigations into the foreseeable future in cooperation with citizens of Menard who hope to properly reconstruct parts of the fort and build an interpretive center. Three years of archeological excavations at the site have yielded a great deal of information, both about the original architecture of the presidio, traceable through vestiges of wall foundations, and about the lives of the people who lived there, represented by recovered artifacts. Artifacts from the site are typical of the Spanish Colonial period in Texas: musket balls, gunflints, horse equipment, hand-forged iron nails, and sherds of imported ceramic olive jars, plates, and bowls. Presidio San Sabá was chosen as the site of the 2003 Texas Archeological Society Field School (see the Texas Archeological Society's website: http://www.txarch.org). Volunteer excavators from all over the state convened in June of that year to work alongside Texas Tech students. At the time of its occupation in the mid-eighteenth century, Presidio San Sabá was the lone bastion of Spanish authority on an otherwise unoccupied frontier. Both in physical size and by the size of its military force, it was the largest and most important military installation in Texas at that time. No wonder that it has been referred to by some as "the ruin of ruins." |

||

Credits and SourcesThis exhibit was written by Elizabeth Cooper. Elizabeth is a graduate student in anthropology at Texas Tech University. She has worked at the Presidio for three field seasons and is Assistant Director of the Texas Tech field school. TBH Spring 2003 Intern, Erin Baudo, prepared the exhibit. For Further ReadingA highly readable and complete account of the founding of the mission and presidio at Menard is Robert S. Weddle's The San Sabá Mission—Spanish Pivot in Texas (1999). This book is in print and is published by Texas A&M University Press. A second important book, still in print, is The San Sabá Papers—A Documentary Account of the Founding and Destruction of San Sabá Mission (2000). Published by Southern Methodist University Press, this collection of Spanish letters and depositions relates to the events surrounding the attack on the mission. The documents were translated by Paul D. Nathan and the book was edited by Lesley Byrd Simpson. The depositions were collected by Captain Parrilla to help in defending his actions during the time leading up to the destruction of the mission. Though they don't tell the complete story, some of the accounts reveal fascinating eyewitness details of the attack and its aftermath. For technical details of Texas Tech University's 1993-1994

archeological testing of Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá,

see The Rediscovery of Santa Cruz de San Sabá, A Mission

for the Apache in Spanish Texas (1995), by V. Kay Hindes, Mark

R. Wolf, Grant D. Hall, and Kathleen Kirk Gilmore. This book is

available from the Texas Historical Foundation, P.O. Box 50314,

Austin, Texas 78763. Web ResourcesThe Texas State Historical Association's Handbook of Texas Online is a magnificent source of detailed entries on the history of the Spanish colonial era in Texas. The address is http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online. Recommended topics related to the Presidio San Sabá are as follows:

Donations to support the preservation and development of Presidio San Sabá. Donations can be arranged by writing to the Presidio de San Saba Restoration Corporation at P.O. Box 638, Menard, Texas 76859. The corporation has 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status.

|

||