Artistic Expression |

|

|

The arid canyons, mountains, and desert basins of the Texas Trans-Pecos region arguably hold the most diverse expressions of native art and ritual expression anywhere in the state. For thousands of years, artisans and ritualists created vivid scenes and symbols on boulders, canyon walls, and overhangs. Others crafted intricate adornments of exotic shell and precious stones along with more perplexing objects incorporating bone, wood, and other materials. In the more recent past, Late Prehistoric village potters created clay vessels, some richly decorated and intended for trade across wide networks. Pictograph artists of the subsequent Historic period recorded an upheaval in the native world—the coming of the Spanish—and lifeways changed irreversibly by horses, firearms, and priests. Throughout time, there was movement of peoples and their material culture across the Trans-Pecos region and beyond. In prehistory, the Rio Grande was not a barrier to this cultural exchange and diffusion. Researchers have found abundant evidence of widespread trade and interaction, no doubt accounting for much of the diversity of Trans-Pecos art. Influences from the west—particularly the massive Casas Grandes cultural center known as Paquime—from the north, including Gran Quivira and the Mimbres cultural areas of New Mexico—and from the south-Chihuahua, Coahuila, and areas farther into Mexico—can be seen in petroglyph and pictograph symbols, pottery motifs, and craft technologies. Whether local or coming from afar, these various artistic expressions are perhaps our most personal communications from the past, affording us a means to glimpse, if only dimly, aspects of spiritual beliefs and cultural traditions across the millennia. Through these media we can experience the worldviews of hunting and gathering peoples as well as that of later, more sedentary villagers and wonder at the changes in economic, social, and ritual systems reflected in their art. While some of the artistic icongraphy of different time periods stands out as unique, other symbols are repeated in different media across the region and beyond. For researchers, these works may be indicators of cultural identities or widespread belief systems. In the section following we look at representative examples of this varied legacy and provide links to sections on Texas Beyond History where more detail from individual sites is provided. In the Hueco Tanks exhibit, viewers also can view a gallery of Forrest Kirkland's watercolor renderings of the site's extraordinary pictographs. |

|

An unusual pictograph panel from Aqua Frio in the Big Bend area incorporates anthromorphic figures and deer in red. Watercolor by Forrest Kirkland, TARL Collections. See full panel |

Artists of the Historic period often painted scenes near much earlier depictions, as is evident on this smoke-stained shelter wall at Hueco Tanks. This elaborate panel was copied by artist Forrest Kirkland in the 1930s. Although symbols of the Jornada Mogollon and earlier cultures may be present, the white figures, including the horseman with elaborate headdress, are attributed to the historic Apache. Painting from TARL Collections. See full panel and Jornada Mogollon designs. |

|

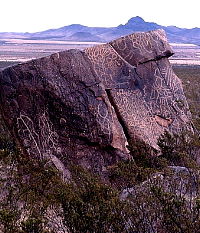

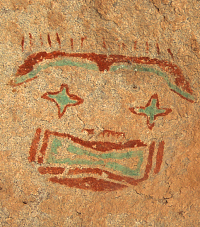

Rock ArtNative peoples took advantage of the wealth of natural rock "canvasses" available throughout much of the region's mountains and boulder-strewn basins. Artists chose prominent landmarks as well as more hidden locales for their work, and we can guess that there was, in many cases, spiritual or ritual significance in the selection of these locations. According to some ethnographic accounts, shamans chose places such as crevices and caves in the rock as "portals" to the supernatural world. Major rock art sites have been documented in all the eastern Trans-Pecos mountain ranges, from the Chisos to the Delaware mountains in the north. Farther west, the Sierra Diablos, Franklins and Huecos and smaller outlying hills hold an abundance of rock art treasures. Researchers have noted the confluence of rock art styles within this broad region-the Pecos River style extending northwestward from the Lower Pecos area, even perhaps traveling up the river, as well as the Jornada Mogollon styles of the west and northwest extending southward almost to the Big Bend. On a broader scale, influences from ancient Mesoamerica have been suggested. Some of the art of the Trans-Pecos, however, is simply unique. Both pictographs-painted depictions on rock-as well as petroglyphs-pecked or carved depictions in rock-are abundant in the region and are attributed to cultures from Desert Archaic to Late Prehistoric, or Formative, times, and into the Historic period. Archaic art, whether pecked or painted, frequently is described as representational and includes animals with hunters wielding weapons, a variety of anthropomorphic figures, as well as patterns of lines and geometric forms. Many researchers have questioned the notion that such hunting scenes are literal depictions of past events but, instead, relicts of "vision quests" or rituals. The act of killing depicted in the scene may have been a metaphor for entering a trance-like state where the animal serves as spirit guide, or, the maker becomes the animal. Petroglyphs and pictographs at Alamo Canyon, southeast of El Paso, may depict this act of transcendence: hunters are shown with body parts morphed into projectile points. Some have legs and arms terminating in projectile points, while others have a triangular shaped body. Human-like figures and faces appearing in rock art scenes also may represent gods or shamans. In the Big Bend area, some of the figures have protrusions, or appendages, such as horns or ears, and outstretched arms. Many of these same motifs also appear in pictographs at Hueco Tanks. In many of these scenes, depictions of deer are intermixed with large renderings of barbed points, similar to the Shumla type. Some researchers believe this affixes a Late Archaic time frame to the artistry, although archeologist Solveig Turpin believes the points are more likely archetypal representations of a point rather than an actual style. In many cases, the same motifs and symbols appear in both painted and carved works. The artistic and ritual expressions of the Jornada Mogollon people, abundant throughout the western Trans-Pecos and into New Mexico, are exemplary of this pattern. Plumed or horned serpents, "rain altars" with step-fret designs, goggle-eyed figures referred to as "Tlaloc," masks and faces appear in both petroglyphs and pictographs. Many of these symbols, particularly those associated with rain and water, are thought by researchers Kay Sutherland and Polly Schaafsma to have derived from cultures in Mesoamerica, perhaps brought to the Trans Pecos area by priests or traders at Casas Grandes. In the shelters and caves of Hueco Tanks, a number of goggled-eyed figures and "rain altar" symbols have been found, along with what is thought to be the largest assemblage of painted masks in North America. Numbering at least 200, the depictions include both solid and outline designs. Some of the visages are adorned with earrings, earspools, and headgear; others are more expressive faces. Petroglyph renderings of the same designs have been found in Alamo Canyon near Fort Hancock as well as at the Three Rivers site in central New Mexico. Many of the same motifs are found in the Black Mountains and Red Hills in Hudspeth County. Turpin found that both these isolated geological anomalies contained a number of pictograph sites which she believes were vision quest locations. They are both places where conditions were grueling: the latter site has no known water source other than shallow tinajas. On the journey, ritualists would have "baked, starved, and thirsted while the wind blew from all directions at once." Other artistic expressions manipulate the elements of the environment as part of the design. Archeologist Robert Mallouf of the Center for Big Bend Studies documented a rare example of rock art termed a petroform in a canyon east of the Rio Grande. "Dancing Rocks," as he whimsically named the feature, is "a curious arrangement of 24 basalt boulders found on a ledge between the sandstone canyon cliffs and the arroyo below. The boulders do not appear to have fallen in a random pattern, but to have been assembled by humans in an intentional display now scattered by erosion. Five of the boulders carry petroglyphs-paired human figures that appear to be holding hands and dancing, a riderless horse, and a rider on horseback." The petroform is thought to have been constructed by early historic period nomads on what may have been a ritual locale. Historic period pictographs incorporate a variety of figures not present in earlier art: horses and mounted riders, crosses and depictions of what are thought to be churches and missionaries, men bearing guns. Depictions of native dancers and figures wearing headdresses have been attributed to historic tribes such as the Apache, who began entering the area as early as the 1400s. |

|

|

|

|

|

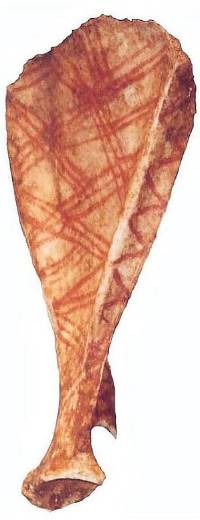

Ornaments and Ritual Objects- "Portable Art"Other types of art can be described as "portable," including small adornments and objects that could be worn, carried from place to place, or left as offerings in shrines or ritual locations. Fortunately for researchers, the dry climate of the Trans-Pecos has preserved a rich collection of these rare, fragile, and often perishable items. Some have been found secreted in caves and rockshelters, others excavated from open camp sites and pueblo villages. While some may have been personal objects, other items appear to have had a place in rituals or ceremonies. Native artisans used a diverse and exotic array of materials to craft these objects: marine shell from the Pacific coast-abalone, Glycymeris, and olivella-as well as colored stones, such as turquoise, malachite, and obsidian. Other items were more simple, incorporating natural materials such as seeds and reed found at Bee Cave Canyon. Many of the elaborate objects left in a small cave northeast of El Paso may have been placed as offerings by ceremonialists of the Jornada Mogollon culture. Some researchers believe the site, known today as Ceremonial Cave, may have been a shrine-perhaps a designated stop where pilgrims took part in prayer and rituals and left their offerings over several generations of time. Among the more unusual objects are a turquoise armband made of fiber basketry; pendants, bracelets, and beads fashioned of turquoise and exotic shell; and small objects made of carved obsidian, known as cruciforms. Several complete weapons-wooden darts tipped with chipped stone points-with small attached bundles filled with tobacco or herbs also were found in the cave. Another unusual weapon-an oversized Perdiz point-was found in a cairn burial attributed to the Cielo Complex culture at the Rough Run site in the Big Bend area. While sporting the characteristic pointed stem and sharp barbs typical of the small Perdiz-type arrow point, the oversized Rough Run point measured nearly 6 cm-at least twice the size of most traditional Perdiz points. Finely made, it had been laid above the deceased individual's head, pointing straight downward and is thought to represent a "ceremonial" piece left as a special offering, rather than an ordinary arrow point tip. Large quantities of small Perdiz points also were recovered, several of which appeared to have been deliberately broken, or "killed," before placement in the burial, according to Center for Big Bend Studies archeologist Andy Cloud. A cairn burial at the Las Haciendas site also contained large quantities of Perdiz points as well as a drilled malachite pendant and kaolinite bead. Ornaments and jewelry made of shell also have been found at the Formative period Ojasen and Gobernadora village sites and the site of a wickiup and tipi encampment at Squawteat Peak. More enigmatic objects marked the site of rituals, including one apparently involving bloodletting. In northern Coahuila, Mexico, the cave known as Cueva Pilote preserves a remarkable array of objects that were clearly used in ritual activities. Archeologists found 18 deer scapulae with geometric designs painted in red and black, agave "pincushions" holding the pointed, needle-like leaf tips for ritual bloodletting, and a quantity of shell beads that likely were part of ritual "flores" or rattles. Unusual objects found at the Bee Cave Canyon site invoke ritual and ceremony involving music, smoking of tubular pipes, and possible offerings. Among a large array of objects, archeologists found two dozen human figurines made of unfired clay and painted with black, red and yellow designs, groundstone metates painted with red and black designs, and a small, flat piece of wood depicting a dragonfly and butterfly. Along with several stone tubular smoking pipes, a notched wooden rhythm stick, and several reed pipes were more puzzling objects: rough stones attached to a fiber cord or wrapped with grass and cactus spines. |

|

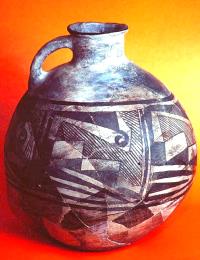

Potters in the western Trans-Pecos created vessels using local clays, such as the simple El Paso Brownware bowl at left, and the large decorated El Paso Polychrome jar of a later time period, center. Distinctive decorated vessels, such as the Mimbres Black-on-White bowl, were acquired through trade or exchange with pueblos in New Mexico or the El Paso Valley. Vessels shown at left and center are from displays at the El Paso Museum of Archaeology; photos by Susan Dial. The vessel in center is from 12 Room House Room, Fort Bliss. The bowl at right is from TARL Collections, photo by Monica Trejo.

|

||

|

|

PotteryPotters began making ceramic vessels in the Trans-Pecos during the Late Prehistoric, or Formative period. Over time, the local, utilitarian El Paso brownware tradition evolved into more decorative types. El Paso bichrome, prevalent in transitional Dona Ana village sites of the western Trans-Pecos, incorporated red and black designs. The later El Paso Polychrome pottery made by pueblo potters achieved a greater level of stylistic sophistication. A large variety of decorated pottery was traded from more distant areas. Distinctive black and white Mimbres and later Chupadero pottery, prevalent in many mid-to late Formative period sites-was produced in the southern and east-central New Mexico area. Many of the painted designs on these vessels, including stepped fret rain cloud altars and geometric border designs, make an appearance also in pictographs of the region. Archeologist Marc Thompson, director of the El Paso Museum of Archaeology, has pointed out aspects of Mimbres duality and "twin" motifs appearing in Jornada Mogollon rock art depictions, several of which appear at Hueco Tanks. Elaborately decorated pottery from the Casas Grandes cultural center southwest of El Paso also was traded to villages and pueblos throughout the region and beyond. Craft specialists there also produced quantities of shell jewelry-bracelets, necklaces, and earbobs-with materials acquired from the Pacific and Gulf coasts. As reflected in its art, the Trans-Pecos in prehistoric times was infused with the ideas and innovations from many cultural areas. The Historic Mission period in the Trans-Pecos saw the union of native pottery styles with symbols borrowed from the Spanish, particularly the inclusion of Catholic motifs on (see Socorro Mission). To learn more about ceramics of the Trans-Pecos, see the Prehistoric Pottery section, which includes a chart of many types and their time periods. Body ArtTattoos and body paint are another form of artistic, cultural, and ritual expression. Particular body designs and symbols as well as piercings and hair colorings often signified clan or group affiliation, or were applied before rituals, ceremonies, or entering battle. Our knowledge of some of this body art comes from accounts of early explorers traveling through the Trans-Pecos. These early records occasionally made note of the appearance and customs of native peoples including the manner in which they ornamented their bodies. In the El Paso valley, early Spanish explorers encountered native groups living along the Rio Grande. The Suma were characterized by tattoo or paint on their faces that appeared as a dark mask. The Mansos were known for their distinctive red-plastered hair. In the La Junta de los Rios region, native peoples were recorded as having a variety of tattoos and body paint. The accoutrements of painting, such as mineral pigments and grinding tools, are commonly found in Trans-Pecos sites, both prehistoric and historic. Although some of these items may represent use for other artistic puposes, it is likely that a great deal relates to body painting. |

|

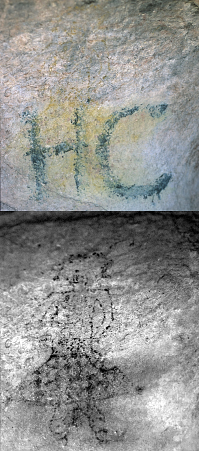

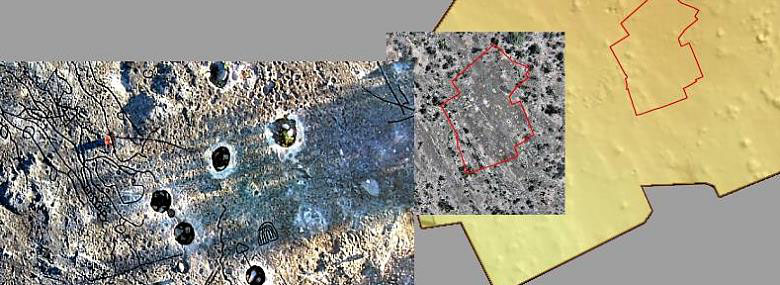

New technologies to capture ancient artistry. This composite of images—each of them insets from much larger data sets—shows the results of combining kite aerial photography and computer imaging to identify and document petroglyphs carved in large expanses of horizontal bedrock at the Graef Site in Reeves County. The three-dimensional map at right denotes the location of the inset, center, a photograph of the actual terrain. The zoomed photo at left details several of the petroglyph elements—meandering lines and discrete elements—shown highlighted in black. The photo below, right, provides a ground level view of one of the same petroglyphs. Photos and graphics by Mark Willis. |

|

Research and DiscoveriesOur knowledge of the art of the Trans-Pecos has been greatly expanded since early travelers sketched the intriguing designs they saw on rocks and canyons, and since artists and archeologists such as Forrest Kirkland and A.T. Jackson began systematic surveys to record the art beginning in the 1930s. Researchers today, such as Mark Willis, Robert Mark, and Evelyn Billo, are applying new techniques to map sites on the landscape and even discover faded or unknown art. Austin archeologist Willis has worked extensively in the Trans-Pecos with kite aerial photography (KAP). Working at sites such as the Graef site in Reeves County with artist Reeda Peel, he combines KAP with photogrammetry to pinpoint locations, create maps and three-dimensional models, as well as photograph rock art panels and individual glyphs and painted symbols. Robert Mark and partner Evelyn Billo of Rupestrian Cyberservices have developed computer imaging enhancement techniques that has served to alert researchers to the vast amount of rock art that remains undiscovered. At Hueco Tanks and numerous other locations, they have "recaptured" art no longer visible to the naked eye and brought into focus pictographs that have faded or otherwise been damaged by humans or weathering. Learn more about their techniques and see more enhanced images in the Rock Art section of Hueco Tanks exhibit on TBH. Radiocarbon dating of pictographs is an evolving science being advanced by Texas A&M chemist Marvin Rowe. His work at sites such as Tall Shelter in the Big Bend, Hueco Tanks, and many others in the Lower Pecos have provided a suite of dates for researchers to work with. Due to the problems of dating carbon from "old wood" and possibility of contamination, however, the dates obtained are not considered fully reliable. Another studies are focused on individual artistic elements. Artist Debra Cool-Flowers, who has examined numerous Jornada Mogollon panels at Hueco Tanks, believes she may have found the "signature" of an individual artist, a crossed-T sign that she has identified on several of the pictographs. This and other stylistic characteristics in the paintings have led her to speculate that they may be the work of a "master painter" at the site, perhaps during the time of the circa A.D.1150 farming settlement at Hueco Tanks. Researchers continue to work with local landowners to gain access to private land and document art at newly discovered sites. Archeologists at the Center for Big Bend Studies, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and the National Park Service, working with independent archeologists such as Solveig Turpin, artists such as Reeda Peel, and members of local avocational groups, such as the El Paso Archaeological Society, have had significant success in this effort as they attempt to record and interpret the art of this massive region. |

|

Credits and SourcesThis section was created by TBH editor Susan Dial and developed for the web by TBH editorial assistant and web developer Heather Smith. LinksEl Paso Museum of Archaeology Rock Art Foundation Rock Art of Hueco Tanks Art of the Texas Plateaus and Canyonlands Print Sources(See also site sections linked above for more extensive lists of reference materials.) Bilbo, Michael, and Kay Sutherland Hyman, Marian, and Marvin W. Rowe 1997 Plasma Extraction and AMS 14C Dating of Rock Art Paintings. Techne 5:61-70. Hyman, Marian, Kay Sutherland, Marvin W. Rowe, Ruth Ann Armitage, and John R. Southon Jackson, A. T. Jensen, Amber, Robert J. Mallouf, Tom Guilderson, Karen Steelman, and Marvin Rowe Kirkland, Forrest, and W. W. Newcomb Jr. Mallouf, Robert J. Rowe, Marvin Rupestrian CyberServices Schaafsma, Polly Sutherland, Kay 1996 Spirits from the South. The Artifact 34(1-2). El Paso Archaeological Society, El Paso, Texas. Sutherland, Kay and Paul Steed Thompson, Marc Turpin, Solveig 1996 West of the Pecos: Prehistoric Adaptations in the Transition to the Eastern Trans-Pecos Region. The Journal of Big Bend Studies 8:1-14. 2002 Rock Art in Isolation: The Black Mountains and Red Hills of Hudspeth County. Journal of Big Bend Studies Vol. 14:1-31. |