Hunter-Gatherer Life along the Frio River |

View looking northeast across the Frio River Valley from Skillet "Mountain," a locally prominent landscape feature, prior to the completion of Choke Canyon Reservoir. Photo by Bob Stiba. |

|

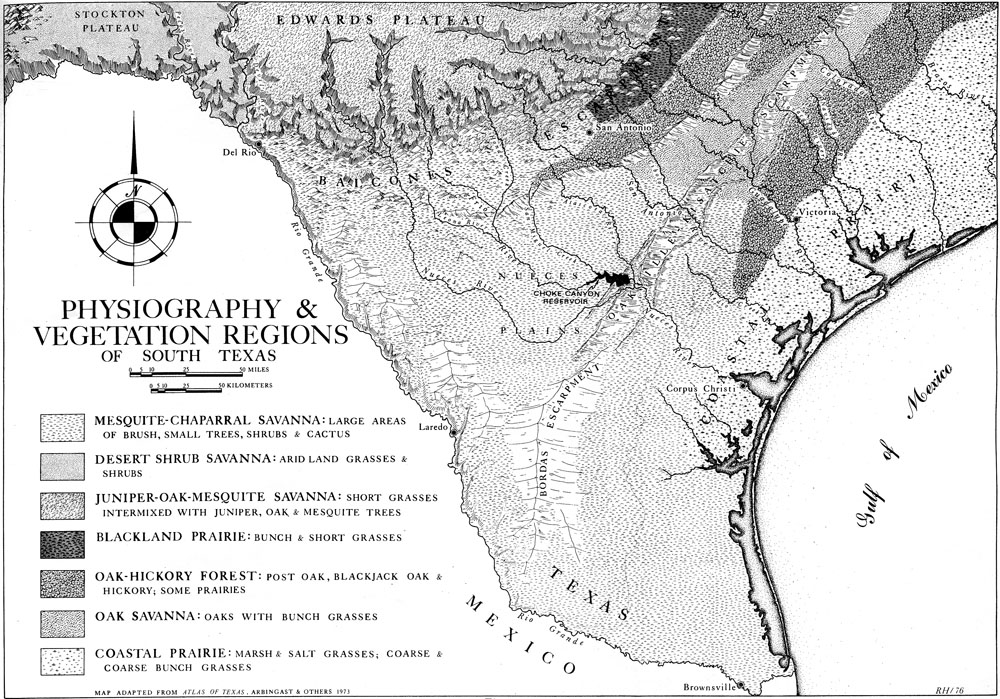

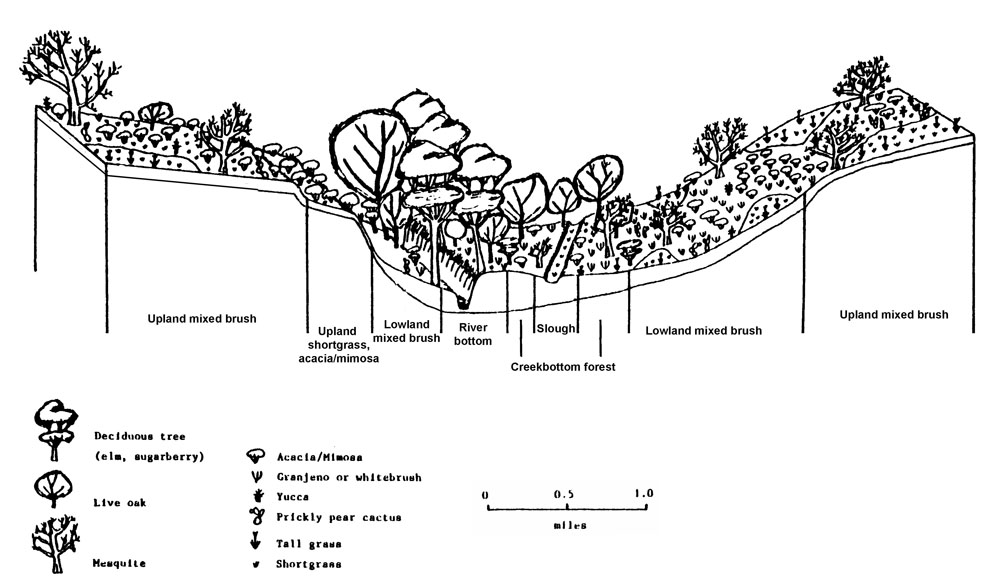

For hunter-gatherers, the coalescent valleys of the Frio, Atascosa, and Nueces rivers (near the aptly named town of Three Rivers) created a rich environment. Yes, dry periods were harder to survive than wet times, but compared to the upland areas of the South Texas Plains, the river valleys were always relatively resource-rich, even in hard times. The several hundred prehistoric sites found during archeological investigation of the Choke Canyon Reservoir on the Frio River attest to the suitability of this land in supporting ancient hunter-gatherers throughout prehistoric times. Local geologic formations, such as upland gravel deposits and gravel bars along rivers and streams, provided ample supplies of chert and quartzite, the raw materials needed for the manufacture of a variety of stone tools. Outcrops of sandstone and tuffaceous siltstone provided rocks used in making grinding implements. They were also used as boiling stones and as heating elements in earth ovens and hearths. Though plant remains are poorly preserved in the local archeological record, we can safely assume (on the basis of ethnohistoric data and findings in the Lower Pecos) that trees and plants provided abundant wood and fiber used for shelter components, tools, tool parts, baskets and other woven containers, cordage, nets, and mats. Clothing and footwear, such as they were, were made from animal hides and woven plant fibers. Warm cloaks and blankets were made of twined and woven rabbit furs or the fur-covered hides of deer and bison. These materials and technologies insulated people from the climate and aided in the extraction and processing of the wild foods that provided sustenance. There is no evidence or reason to believe that prehistoric people in the Choke Canyon area, or anywhere in the South Texas Plains, produced any of their own food through farming or raising livestock. That being the case, what wild plant and animal foods were available to prehistoric people along the lower reaches of the Frio River? The brush species, in modern times a blight on the countryside, were important food providers to prehistoric people. For instance, mesquite trees have a nutritious bean that was ground up to make a protein-rich flour for making breads and gruels. In the spring, the prickly pear cactus provided tender new-growth (and spineless) leaf pads that could be eaten raw or baked (known in Spanish as nopalitos). In the summer, the prickly pear yielded fruits that had both a sweet flesh and protein-rich seeds (called tunas in Spanish). Judging from early Spanish accounts, prickly pear was a major staple. |

|

|

|

|

Other edible fruits would have included agarita, spiny hackberry, yucca, tasajillo, and persimmon. Walnuts, pecans, acorns, grass seeds, and a variety of other seeds, beans, and nuts were also seasonally available. Shrubs and forbs growing along the river and in nearby upland prairies provided edible blossoms and foliage and, most importantly, a variety of tubers, bulbs, and roots (collectively, geophytes) that could be eaten raw or baked to make them fit for human consumption. These were important sources of carbohydrates, especially the geophytes, which were among the few plant resources available in the winter and early spring. Meat foods and animal products used to make tools, ornaments, clothing, and other coverings included many different land and water animals. Out of the Frio River and its major stream tributaries came fish such as freshwater drum, gar, catfish, bass, and minnows. Aquatic turtles, snakes, mussels (freshwater clams), and the occasional alligator were also taken. On land, the animal spectrum hunted, netted, trapped, or hand-caught ran from the mighty bison down to the lowly field mouse. In descending size order, the mammals included bison, whitetail deer, antelope, mountain lions, wolves, javelinas, bobcats, coyotes, raccoons, opossums, skunks, jackrabbits, cottontails, squirrels, rats, and mice. Of those, deer, rabbits, and rodents were the most dependable sources of meat. Bison herds came through the region only periodically when the grasslands of their regular habitat of the Southern and Central Great Plains were less attractive owing to drought and perhaps intensive hunting. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reptiles, such as lizards, frogs, terrestrial snakes, and tortoises were all taken. Turkeys, quail, doves, ducks, and other birds were hunted and trapped. The eggs of all birds, turtles, and snakes would have been collected and eaten with enthusiasm when found. Even land snails, especially the genus Rabdotus, were gathered, roasted (steamed or boiled), and eaten. Insects and their larvae were important foods at certain times of the year. Grasshoppers and cicadas are especially plentiful at times and likely contributed important proteins and fats to the hunter-gatherer diet. |