|

At the far west end of Choke Canyon Lake, not far from Tilden, Texas, is a picturesque mesa known as

Skillet Mountain. The Frio River runs below the north end of the mesa. This area of the Frio River

valley is only flooded at times when Choke Canyon Lake is at maximum flood stage.

While archeologists were working at Choke Canyon, the owner of the ranch encompassing Skillet Mountain

decided to clear some brush. This was accomplished using a bulldozer pulling a "drag" made of iron anchor

chain and train rails. In the process of clearing the brush, the bulldozer exposed an important Late

Prehistoric site which was given the name "Skillet Mountain #4." This site is a classic example of a Late

Prehistoric buffalo hunters' encampment. (As the site's full name implies, several other archeological sites were recorded around Skillet Mountain, but #4 was the only one whose name lives on, often in just the shortened form, Skillet Mountain.)

The site was situated on the higher ground inside an oxbow loop of an abandoned channel of the Frio River.

Since the hunters were camping at the site comparatively recently (somewhere between A.D. 1250 and 1500),

the camping debris was not as deeply buried as at older terrace sites such as Possum Hollow and Gates-Rowell. In fact, the remains were very shallowly buried, which is why they became partially exposed by

the bulldozer activity. Yet, due to river flooding, the camp was rather quickly covered by sediment and

the camping remains were sealed in place very well. Possibly because of soil conditions, or because the

remains were not very old, there was very good bone preservation at Skillet Mountain #4. The remains included very

obvious large bones from buffalo as well as the smaller bones of other animals. Excavations at this camp

yielded two hallmarks of the Late Prehistoric Period: arrow points and plainware pottery.

Though shallow - only about 40 cm or 15 inches deep - the Skillet Mountain archeological deposits

were stratified. The layering of the Late Prehistoric debris in this deposit indicates that there was

more than one episode of camping at the site. In between camping episodes, the river overflowed its banks and

left sediments that separated the camping trash left by each group who used the site. These various

encampments might have occurred over less than 100 years, but certainly over no more than 400 years. By

the standards of Choke Canyon prehistory, this was a very short period of time.

Overall, this Skillet Mountain camp was about 48 meters (about 145 feet) in length and 12 meters (about 36 feet)

in width. Forty-seven square meters of the site were excavated by archeologists. This excavation

revealed fascinating patterns of camping activity by the Late Prehistoric people who used the site.

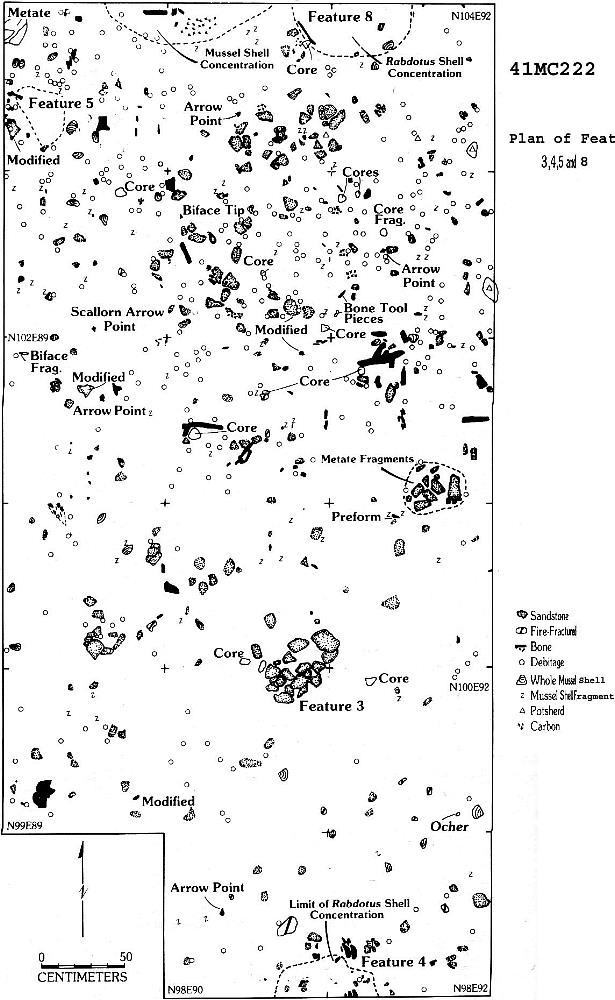

Eight features were defined, which were made up of various combinations of animal bone, sandstone

hearthstones, mussel and snail shells, chipped stone and ground stone tools, and chert debitage.

Analysis of the animal bones, ground stone tools, and mussel- and snail shell collected at Skillet

Mountain #4 shows that these Late Prehistoric people were living off of many of the same natural foods

that had traditionally supported Archaic hunter-gatherers for thousands of years. The good

preservation of animal bones gives a much fuller picture of the variety of animals that these people

hunted, netted, trapped, and caught. Buffalo was prominent. The big bones of these animals predominated

in the Skillet Mountain collection. In addition to buffalo, there were also bones of deer,

javelina, coyote or dog, bobcat, alligator, rattlesnake, rabbit, rat, turtle, lizard, frog, catfish, gar,

and other fish. Very likely this variety was also typical of Archaic people in the region, too, but the bones

of these animals haven't survived as well in older sites. Other parallels with the Archaic include

metates and manos, suggesting processing of seeds, beans, and nuts. Late Prehistoric people also relied

on river mussels and land snails in the same way as did Archaic people. |

Bulldozer at work chaining brush to promote grass growth for cattle, some 5-years before the lake would claim this area. This work exposed bison bones at the Skillet Mountain site and led to excavations.  |

|