Prairie-plains frontier after 1855.

|

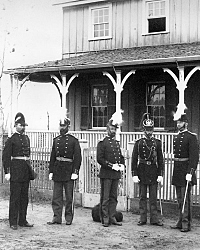

Powder magazine at Fort Belknap.

A powder magazine, or armory, was usually one of the

first, and most secure, structures erected at a frontier

army post. The magazine at Fort Belknap would have stored

the post's powder, lead, and other munitions. It is

the only original structure remaining at the fort site.

|

Ruins of house at Camp Cooper. The

post, established in 1856, was situated on a bend of

the Clear Fork near the heart of the Upper Reserve.

The site is now on private land. Photo by Bob Stiba.

|

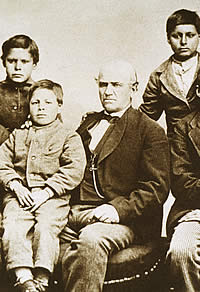

Cynthia Ann Parker with daughter,

Prairie Flower, circa 1860-1870. Parker, who had been

kidnapped by Comanches in the 1836, went on to adopt

Indian ways, marrying an Indian warrior and bearing

two sons, one of whom was future chief Quanah. Photo

courtesy Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.

|

|

Texas authorities were so anxious to have the Indians

gone that, in the abruptness of their departure, they

were forced to leave most of their possessions behind.

It would not be the last time the Tonkawa were so rewarded

for their fealty to Texans.

|

Cannon at Fort Belknap. Although

they were used infrequently during the Plains Indian

wars, artillery could usually be found at a frontier

Army post. Civilians obtained home-made cannon for their

private forts, to be used in the event of Indian attack.

The little guns produced smoke and noise, but seldom

any casualties.

|

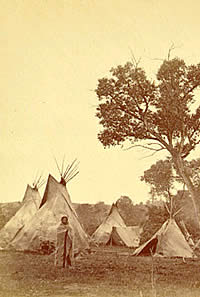

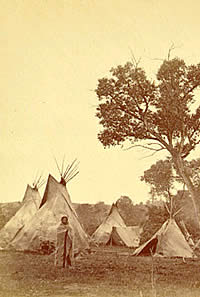

Comanche camp. Camps such as this

were targeted by the Army using a strategic policy of

striking the non-reservation Indians where they lived

in Indian Territory. Women and children were frequent

casualties of the aggressive campaigns.Photo by William

Soule, courtesy of Wichita State University.

|

Forts, roads and trails after 1866

in the Prairie-Plains region.

|

|

None of these posts—those of the new "second

line" any more than those of the earlier "first

line"—inconvenienced the Comanche and the Kiowa

in the slightest degree. During the years 1848-1855, only

two engagements with Indians were fought by troops from any

of these posts. One of those was an Indian attack on soldiers

at Fort Chadbourne. Phantom Hill, with poor wood and worse

water, was soon abandoned by the army. Fort Belknap was relegated

to guarding the reservations the state had established for

some of its Indians.

After years of prodding by U.S. officials, the

Texas legislature in 1854 authorized the creation of two reservations,

one on the Brazos River below Fort Belknap, and the other,

the "Upper Reserve," on the Clear Fork. The Brazos

Reservation housed some 1,000 Anadarko, Caddo,Tawakoni,Tonkawa,

and Waco Indians. The Upper Reserve was able to attract only

about 450 of the Penateka Comanche—"Honey Eaters"—who

had ranged mostly south of the Brazos River. The job of the

army was to keep these Indians on their reservations, and

to keep white settlers away from them.

The forts in the region soon took on a new role,

however. The arrival of the army's 2nd Cavalry late in 1855

presaged a dramatic change in military strategy. Its commanding

officer was Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, a veteran of several

Indian campaigns and a former secretary of war of the Republic

of Texas. Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee was second in command.

The companies of the 2nd Cavalry were dispersed

along a line that mimicked the "second line" of

forts, but generally placed the horse soldiers closer to established

settlements where grain for the regiment's animals was more

available. Lee, who was effectively in command for much of

the regiment's tour in Texas, took station at Camp Cooper,

established in 1856 on the Clear Fork near the heart of the

Upper Reserve. Most of the "second line" forts then

became bivouac, rendezvous, and supply points for the wide-ranging

troopers as they scouted for Indian trails, intercepting and

pursuing the raiders they could find.

Another strategic change was a policy of striking

the non-reservation Indians where they lived-in the Indian

Territory north of the Red River. The most ambitious of these

campaigns followed a Texas ranger model. In the spring of

1858, veteran Indian fighter John S. "Rip" Ford

received a gubernatorial appointment as "senior captain

commanding Texas frontier." With a hundred or so rangers,

and about an equal number of Brazos reservation Indians led

by agent Shapley Ross, Ford struck the Canadian River camp

of the Kotsoteka chief Iron Jacket in the Antelope Hills of

the Indian Territory. Iron Jacket and 75 other Comanche were

killed by the combined attack force, which lost two killed

and three wounded. An additional 18 Indians were captured,

mostly women and children, as well as about 300 horses. The

village and its contents were destroyed.

Four months after Ford's return, a force of

2nd Cavalry under senior Captain Earl Van Dorn moved into

the Indian Territory with a detachment of the 1st Infantry

and 60 Indian auxiliaries from the Brazos agency. The Indians

were led by the agent's 20-year-old son, Lawrence S. "Sul"

Ross. They spied a large number of Comanche-—Buffalo

Hump and his Penateka band—camped near a Wichita village

in the valley of Rush Creek. Van Dorn struck the Comanche

camp at dawn. The fight lasted for more than an hour, and

when the surviving Comanches fled, they left 56 warriors and

two women dead on the field. Van Dorn lost one officer and

four enlisted men killed. He, Ross, and nine enlisted men

were seriously wounded.

In the Spring of 1859, Van Dorn again led a

force beyond the Red River, this time attacking a Kotsoteka

village on Crooked Creek, in modern Kansas. Two enlisted men

died and 10 were wounded, along with two officers and two

Indian scouts. None of the Comanches escaped; 50 were killed,

50 were wounded, and 37 (32 of them women) were captured.

The army's aggressiveness did not stop Comanches

from raiding in Texas, nor their Kiowa allies. But on the

eve of the Civil War, the army and Texas rangers were trading

the Indians blow for blow. In mid-December of 1860, a company

of rangers under "Sul" Ross combined with a detachment

of the 2nd Cavalry to attack a Comanche camp on the Pease

River. The captured villagers included Cynthia Ann Parker

and her daughter. Ross reported that Peta Nocona was among

the 14 Comanche dead. Although his son, Quanah, later disputed

that assertion, evidence suggests that Peta died at or about

that time, perhaps from wounds received in that battle.

One of the last large undertakings of the 2nd

Cavalry was to assist in the removal of the Texas reservation

Indians to the Indian Territory. Almost from the beginning,

white settlers had coveted the reservation lands. Raids by

northern Comanche and Kiowa, as well as white thievery, were

blamed on the reservation Indians. The bands living on the

Brazos Reserve—the Tonkawa especially—were doubly

wronged, as they probably were innocent of most charges and

had served as valued scouts and warriors with the rangers

and the army.

Attacks on the reservation Indians increased

nonetheless, and in 1859 agent Robert Neighbors succeeded

in obtaining new lands for them north of the Red River. The

2nd Cavalry's Major George Thomas led an army escort that

accompanied the Indians on their journey. Texas authorities

were so anxious to have the Indians gone that, in the abruptness

of their departure, they were forced to leave most of their

possessions behind. It would not be the last time the Tonkawa

were so rewarded for their fealty to Texans.

Secession and the Civil War threw frontier settlers back onto

their own resources and methods. The state's efforts—establishment

of the Frontier Regiment of full-time soldiers and, later,

the militia-style Frontier Organization—were significant,

but they were not nearly enough to protect the settlers from

the newly emboldened Indian raiders. At war's end, settlement

clung tenuously to the outlying counties. With state-financed

defenses prohibited during the Reconstruction period, the

frontier began to depopulate and dissolve.

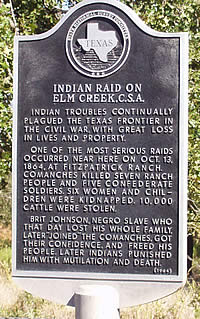

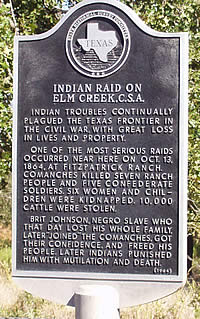

The October, 1864, Elm Creek Raid in Young

County was typical of the trauma of those years. A force of

Kiowa and Comanche estimated at 700 warriors struck a string

of farmsteads along Elm Creek near its confluence with the

Brazos River above Fort Belknap . Eleven settlers—men,

women, and children, black and white—were killed, and

seven women and children, including the wife and two of the

children of black frontiersman Britton Johnson, were carried

away. Eleven houses were sacked or burned. The raiders eluded

pursuit and returned to the Indian Territory.

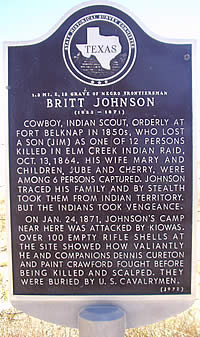

Johnson would make four trips into the Comancheria

to recover what remained of his family (the Indians had killed

his oldest son during the raid). All the white captives but

one also would be returned. Other frontier folk would not

be so courageous, skillful, resolute, or lucky as Johnson.

A compilation of reports from several—but not all—frontier

counties showed 163 settlers killed by Indians, 24 wounded,

and 43 carried off from the summer of 1865 through the summer

of 1867.

Although returning to Texas en masse in mid-1865,

the U.S. Army was slow to either recognize or respond to the

frontier situation. Mounted troops did not return to the upper

Brazos area until 1866, with modest detachments of the 6th

Cavalry posted at civilian settlements at Jacksboro, Weatherford,

and Waco.

|

Plains Indian Camp. The horse changed

the way of life of the Comanche, and came to be one

of the defining cultural attributes of the southern

Plains Indians. Painting by Nola Davis,

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

Site of the Upper Reserve, one of

two Texas Indian reservations intended to control Indians

on the northern Texas plains. The reservation was populated

chiefly by Comanches. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Robert Neighbors' gravesite in cemetery

near Fort Belknap. Frontiersman, soldier, and Indian

agent, Neighbors faithfully served the Republic of Texas

and the U.S. government during the 1840s-1850s.

|

Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, commander

of Camp Cooper on the Clear Fork of the Brazos.

|

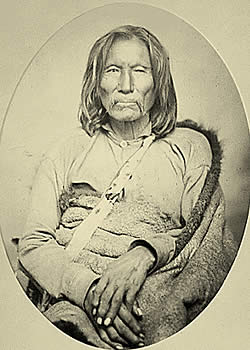

Johnson, chief of Tonkawa scouts

under Ranald Mackenzie in north Texas. Although the

skills of the Tonkawa scouts were greatly valued by

the Army, the tribe was ultimately betrayed by the United

States. Photo courtesy of Lawrence Jones, III. View

large image. |

Beef issue. Food, clothing, and other supplies were

used as inducements to attract Plains Indians to leave

their semi-nomadic lifestyle and move to reservations.

The women and children in this 1892 photograph are

butchering a cow or steer obtained during a reservation

"beef issue." Photo courtesy of NAA-SI.

|

Site of the Elm Creek raid in 1864

in which 12 people were killed and 6 women and children

kidnapped by Comanches.

|

|

Saturday Aug 5/65. The weather is hot and dreary.

Times are hard and bad. Indians thick and plenty trying

to brake (sic) our country. I heard they had robed (sic)

Ike Nickersons house the other day over on hubbard’s

creek. If we don’t get protection shortly and the

Indians continue to do as they have been doing for a

month back the country will certainly brake up.

-Excerpt from Diary of Susan E. Newcomb, Fort Davis,

Stephens County, Texas, 1865.

|

|