This spearpoint from the Gault site

is a classic Clovis point.

Click images to enlarge

|

Mike Collins points out an artifact

at the Gault site. The disturbed area is a trench where

machines have been used to remove overburden—the

site's massive Archaic deposits were thoroughly churned

up by artifact collectors over a 60-year period.

|

His license plate says it all—Collins

lives and breathes Clovis.

|

The Black Prairie was a grassland

for at least the last 15,000 years and still would be

today if the grazing, fire control, agriculture, and

concrete had not all but spelled its doom. Landowners

Bob and Micky Burleson (on right) have restored native

grasses on their property near the Gault site. Researcher

Marilyn Shoberg gathers Little Bluestem for experimental

work. Dense grasslands provided Clovis peoples with

a ready source of building materials—thatched huts

can be constructed in a matter of hours.

|

Looking out across the uplands from

the edge of the wooded valley at the Gault site.

|

For over 13,000 years people have

been picking up flint at the Gault site. And yet, modern

flintknappers have hauled away pickup loads of it. Still,

you cannot walk 10 feet along the edge of the valley

without stepping on flint.

|

Clovis points from the Gault site.

(Click to see full image.) The yellow staining is caused

by iron-rich groundwater, while the white encrustation

is calcium carbonate, which is also carried by groundwater.

In some areas of the site, the lower Clovis deposits

are beneath the water table and can only be reached

during dry spells and with the aid of pumping.

|

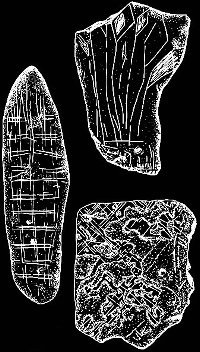

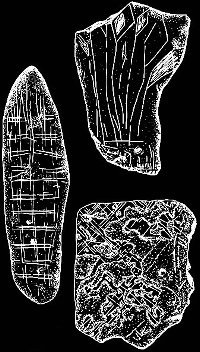

Clovis blade cores. These distinctive

artifacts are blocks of chert (flint) that have been

carefully prepared ("set up" by chipping and

edge grinding) for the removal of prismatic blades.

This highly specialized technology allows a skilled

flintknapper to maximize the amount of useful cutting

edge that can be generated from a single chert cobble.

|

Clovis blades, a few of the hundreds

of specimens that have come from the Gault site. These

were used as is, as cutting tools, or were further modified

to create a variety of more-specialized implements.

|

Incised stone. As you can see, these

are not random scratches, but carefully patterned, precise

lines almost certainly cut with sharp blades or flint

chips.

|

Incised stone.

|

Clovis blades were used to make various

kinds of tools including hide or endscrapers (the two

specimens on left) and gravers with tiny beaks (two

on right). The small, delicate gravers hint at some

sort of specialized work.

|

Researcher cuts Little Bluestem grass

with experimental blade.

|

Scapula (shoulder blade) of an Ice-Age

horse from the lower Clovis deposits at Gault.

|

Mammoth mandible exposed in soggy

lower deposits at Gault. Because of the high water table,

archeologists can only excavate in some areas of the

site during prolonged dry periods or with the aid of

continuous pumping.

|

One of several large excavation areas

at Gault. The Clovis deposits are in the lighter sediment

below the dark band and continue into the upper gravels

visible at the right.

|

Clovis point and Clovis biface.

|

One of two Folsom ultra-thin bifaces

from Gault (click for full image). Some experts believe

that Folsom bifaces are so thin because they were designed

to be light enough to travel with. In contrast, Clovis

bifaces (points, too) are often much thicker and heavier.

|

|

For most students of archeology, "Clovis"

conjures up a vision of a distinctive spear point like the

one shown on the left and of small groups of "big game"

hunters killing Ice-Age elephants as they migrated across

North America. For over five decades the Clovis-first hypothesis—the

idea that Clovis hunters were the first people to explore

the New World—has been a fundamental part of the story

of the peopling of the Americas. Clovis peoples with their

remarkably sophisticated hunting technology were seen as the

first pioneers, highly mobile hunters who walked to North

America via the Bering Land Bridge. Once below the Ice Sheet,

small groups of Clovis hunters and their families expanded

rapidly across the continent killing mammoths so effectively

that the species was pushed over the brink of extinction.

Or so the standard story goes.

In the past decade, the Clovis-first hypothesis

has come under attack from many directions. There have been

multiple claims of earlier, pre-Clovis sites in North and

South America, none totally accepted, but several very credible.

And then there are the early skeletal remains found in North

America, such as the controversial Kennewick Man, whose features

are said to more closely resemble certain Caucasian populations

than later Native Americans. Adding to this, some stone tool

experts have made a case for a close resemblance between Clovis

technology and that of Late Paleolithic Europe. In the last

few years these claims, pro and con, have been reviewed in

Time, Newsweek, New Yorker, National

Geographic and on the Discovery Channel, among

others.

Meanwhile at the Gault site deep in the heart

of central Texas, Clovis culture is being reconsidered week

by week, midway through a planned five-year dig. The emerging

view hardly resembles the Clovis story known to generations

of archeology students. Instead of a new group of people exploring

an unknown land, we seem to see a people thoroughly familiar

with their surroundings. Instead of highly mobile elephant

hunters, we see what looks like a full-blown generalized hunting

and gathering culture living in the same kind of places and

doing many of the same kinds of things that characterized

Archaic-era life all across the continent a few thousand years

later. This is more than a new spin, this is a whole new way

of thinking about what is still, to many, America's earliest

recognizable culture.

The evidence presented here

is so new that most of it has yet to be reported, at least

not in a proper scientific sense. Research at Gault

site continues as does laboratory research and reporting. Several of the nation's leading Paleoindian

experts and specialists in various subfields and dozens of

their undergraduate and graduate students are working on different

aspects of the site. In other words, what follows is merely

a glimpse of what is to come, a peek behind the scenes and

into the head of Dr. Michael B. Collins, the lead researcher

who heads up the project. This is what he now (2001) thinks Clovis

life may have been like based on the emerging evidence. Like

any good scientist, he reserves the right to change his mind.

Collins fully expects the next few years will bring even more

surprises at Gault and elsewhere that will help paint a more

complete and accurate picture of the Clovis past.

Born and raised in Texas, Collins knew in high

school that he wanted to become an archeologist (see "A

High School Student Discovers Bone"). The Gault Project

brings together the three principal themes of his career:

lithics, early Paleoindians, and geoarcheology. His interest

in the early peoples of the New World started when he first

found Paleoindian artifacts around the playa lakes near Midland,

Texas, while still a teenager. He studied archeology and geology

at the University of Texas and then went on to get a Ph.D.

from the University of Arizona. As a stone tool expert he

is well known for his work with Tom Dillehay on the extremely

early Monte Verde site in Chile as well as a recent book,

Clovis Blade Technology (1999, UT Press). His interest

in geoarcheology, the marriage of archeology and geology,

developed as a natural outcome of his interest in Paleondian

cultures. Collins has worked on archeological projects in

many states, countries, and continents, none (with the possible

exception of Monte Verde) more exciting or important than

the Gault site. Being able to investigate a world-class archeological

site less than an hour's drive from either his Austin home

or his Williamson County farm is a dream come true for "Dr.

Clovis."

Ecotones and Endless Flint

To understand why Clovis peoples repeatedly

came to Gault and apparently stayed for quite some time, you

first have to know where it is and what it had to offer. The

Gault site is located in central Texas about 40 miles north

of Austin, halfway between Georgetown and Killeen (Ft. Hood).

It sits near the head of a small creek in a small wooded valley

just at the point where a number of springs come together

to form a clear, cool vigorous stream that has never gone

dry in historic times. This valley is one of many that cut

through the eastern flank of the vast limestone Edwards Plateau

that stretches far to the south and west. The Gault site is

in the northern part of the Texas Hill Country within the

Lampasas Cut Plain, where, as its name implies, the limestone

plateau is somewhat flatter and "cut" by many incised

stream valleys.

A three-hour walk down the creek valley, the

limestone country ends abruptly at the Balcones Escarpment

and the Black Prairie begins. This geological fault zone is

one of the most impressive ecotones in North America, places

where different environments come in contact. Moving east

along the creek, almost everything changes in just a few miles—geology,

hydrology, soils, plants, and animals.

The Black Prairie, so named for its rich black

"gumbo" clay soil, was a grassland for at least

the last 15,000 years and still would be today if the grazing,

fire control, agriculture, and concrete had not all but spelled

its doom. Spanish explorers in the early seventeenth century

rode their horses through grass so thick and deep in many

places that only the mounted riders could see where they were

going. They found plenty of buffalo and antelope to hunt on

the Black Prairie but when they turned west and entered the

rugged up and down world of the Texas Hill Country, they had

to rely on deer and turkey. They found dense, towering bands

of hardwood forest along the streams and an oak savannah in

the uplands with mixed grasses and trees, many of them stunted

and confined to mottes by periodic range fires.

Moving from the grand scale to the local, the

Gault site itself sits on a smaller scale ecotone that is

still obvious today even to the casual visitor. The road to

the site leads through the typical rocky limestone rolling

hills with very little soil and lots of cedar (juniper), live

oak, mesquite and prickly pear. As you approach the site,

the road drops off into the valley—only about 45 feet

lower, but what a difference. The deep, well-watered soils

provide habitat for huge hardwood trees—burr oaks, walnuts,

pecans, ash, elm, bois d' arc, and a dozen more species including

willow and cottonwood. In a word, it is lush. While we don't

have an accurate idea of what the local vegetation was like

in Clovis times, the contrast between valley bottom and the

surrounding uplands would have been just as stark.

So the Gault site was located on ecotones, large

and small, in a small, protected wooded valley with a spring-fed

stream. But it had one other important thing going for it—a

nearly inexhaustible supply of extremely high quality flint

(chert). The flint occurs as stream-worn cobbles along the

creek and it weathers out of the bedrock along the valley

slopes and in the uplands surrounding the site. For over 13,000

years people have been picking up flint here and yet modern

flintknappers have hauled away pickup loads of it. And still

you cannot walk 10 feet without seeing pieces of flint. Some

of the larger nodules are the size of a fat watermelon.

They Came To Stay

Most known Clovis sites fall into one of four

categories. By far the most numerous are places where isolated

finds of Clovis points are made. The next most common are

kill sites, places like Lehner and Murray Springs in southeastern

Arizona or Domebo in south-central Oklahoma where elephant

bones and Clovis artifacts were found together. And then there

are Clovis caches, isolated places were Clovis points, bifaces,

blades, or blade cores are found in tight piles thought to

represent hidden stashes. Finally, there is the rarest category,

camps—places where Clovis peoples stayed put long enough

for considerable debris to build up. Some camps occur in rockshelters

and others in open settings, but most known Clovis camps appear

to be the result of fairly brief stays. In contrast, the Gault

site is clearly a major base camp, a place where people returned

repeatedly and probably stayed for lengthy periods of time.

How do we know? Well for one thing it is a very

large site. Imagine a football field. Now add a second one

beside it. Now add two more pairs of fields end to end. And

this is only the core area of the site measuring about 80

by 300 yards where Clovis materials are known to be concentrated.

The entire Gault site covers an area about 90-100 yards wide

by about 650 yards long. Not all of this area has been tested

yet, but enough to get a fairly good idea of what lies beneath

the surface. The evidence is not spread uniformly; some areas

have much greater artifact densities than others. And it is

also clear that some of the deposits have been washed away

by floods—concentrations of Clovis artifacts have been

found within gravel deposits along the creek. It is not just

large, but incredibly rich. The Clovis deposits average about

40 centimeters (16 inches) thick but are sometimes twice that

or more, and in places the deposits contain unbelievably large

numbers of Clovis artifacts. Collins guesses that the Gault

site may have already yielded as much as 60% of all excavated

Clovis artifacts known today.

Base camps, as the name implies, are places

where people stayed for a while and ventured out from, repeatedly.

One characteristic they have is "assemblage diversity"—lots

of different kinds of artifacts. The diversity already recognized

at Gault is astonishing. There are many Clovis points—finished

points, worn out points, half-made points, resharpened points,

and lots of fragments. And Clovis bifaces—big heavy bifaces,

small thin bifaces, bifaces broken in manufacture, and several

kinds of specialized bifaces. There are also hundreds of Clovis blade

cores and blades—large ones, small

ones, crested outer blades, thin inner blades, broken blades,

and used blades. And then there are the blade tools—end scrapers

made on blades, serrated blades, blades with sharp graver-like

beaks, and blades with incredible use-wear traces. The finding

of several adzes or wood-working tools was quite unusual—this

tool form was not known previously from other Clovis sites,

although it occurs more commonly at later sites. Another interesting artifact from Gault is a bone or ivory rod, found in the ancient

gravel deposits of the creek amid definite Clovis artifacts.

It is very similar to specimens found in other Clovis sites.

Among the unprecedented finds at Gault are the incised stones—smallish,

smooth limestone rocks and chert (flint) flakes that have various patterns and designs

formed by shallow lines almost certainly made with sharp flint

flakes. More than 100 of these "mobile art" objects

are known from Gault, from early Paleoindian contexts as well as later Archaic-age deposits. The Clovis-age specimens may represent the earliest examples

of representational art in North America.

The artifact diversity obviously means that

many different tasks were carried out at the site and probably

elsewhere by work parties who returned to Gault. The Gault

researchers are not ready to enumerate these tasks in much

detail, but some patterns are already clear. First and perhaps

foremost, the Gault site was a major tool-making locality—a

lithic workshop where a great many stone tools were made,

most out of flint. All stages of tool-making were carried

out from the first stages of "primary reduction"

(breaking up large cobbles into usable pieces) to the final

stages of putting the finishing touches on a completed artifact.

And beyond—there are many resharpened and broken tools

at Gault that show people were "retooling"—taking

the time to replace broken and worn parts (such as the tips

of spears) with sharp new ones. While evidence is less direct,

a great deal of wood working, binding, and so on must have

taken place there as well. Tiny gravers—very small, delicate

stone tools with sharp beaks—hint at some sort of specialized

work—scarifying (scratching the skin to draw blood or

allow tattoo pigment to absorb) or incising bone, wood, or stone?

Although bone preservation is generally poor

in the Clovis deposits, there are enough bones of mammoth,

horse, and bison to suggest that these animals were killed

not too far away and at least partially butchered at the site.

Many tools speak to hunting and butchering—Clovis points,

bifaces and sharp blades with meat polish, and heavy choppers

probably used to dismember large animals. Endscrapers made

on blades suggest that hide working was another typical activity.

One of the most promising avenues for documenting

the daily activities of the Clovis peoples who stayed at Gault

is through use-wear analysis of stone tools. Using this approach,

Gault staff researcher Marilyn Shoberg has already identified

three very different tasks that Clovis blades were used for:

butchering, grass-cutting, and woodworking. She looks at individual stone

tools under 200x magnification using a binocular microscope

with polarized light and special eye pieces designed just

for this kind of work. At 200x, the edge of a Clovis blade

looks like an alien world complete with craters and mountains.

These micro-topographic features are the actual surface of

the stone tool.

When stone tools are used repeatedly, once-sharp

edges become dull and rounded and polish forms. Different

kinds of contact materials create different kinds of polish—high

polish, dull polish, domed polish and more. And when hard

particles, such as sand grains adhering to a hunk of mammoth,

come into contact with the polished edges, they leave striations—scratches

and gouges. The orientation of these blemishes tells Shoberg

which direction the tool was being pulled (or pushed).

The patterns seen on archeological specimens

must be compared to experimental tools used for known purposes

on known materials. These serve as control or reference samples.

Magnified surface of a serrated Clovis

blade. This 200x view shows well-developed polish and intersecting

striations thought to result from cutting up meat. Photo by

Marilyn Shoberg.

The picture above is the surface of a serrated

Clovis blade. The shiny polish is the kind that is associated

with cutting meat—butchering. Notice the criss-crossed

striations. The triangular pattern left by the intersection

of the striations is very characteristic of a tool used repeatedly

to cut the meat of a large animal. The different striation

directions imply that the blade was held in different ways

or at least at different angles.

Now compare this with the first picture on the

right showing the magnified edge of a Clovis blade with obvious

polish. Notice that most of the surface is completely smooth

and the edge heavily rounded. The polish is continuous, smooth,

and has numerous small pits and medium-sized comet-shaped

pits. This kind of polish is consistent with use in processing

plant material high in silicates, and is often referred to

as "sickle gloss." The edge (at the bottom of the

picture) is heavily rounded, which means that this tool was

used for quite some time.

Finally, compare the first two photos with the

second (lower) picture on the right showing the magnified

edge of an experimental blade used to cut Little Bluestem

grass, the kind that formerly covered much of the Black Prairie.

After 2000 strokes, characteristic silica polish is just forming

in a continuous band along the edge of the blade, and pockmarked

areas of polish extend back from the edge. The areas of polish

are not as large and continuous on the experimental blade

when compared to that on the archeological tool, suggesting

that the experimenters have many more thousand strokes to

put in. But the characteristic form of the polish on the replica

tool, with small pits and linear features parallel to the

edge of the blade, is very similar to that found on the archeological

tool. This comparison supports the hypothesis that the prehistoric

blade was used to harvest and/or process grass or reeds.

Shoberg has just begun to look at the Clovis

tools from Gault. She and other researchers will spend hundreds

of days staring under the microscope, taking notes

and photographs, and comparing archeological tools with more

experimental ones. Tedious work to be sure, but the result

will be a much more complete view of what Clovis peoples were

doing with their finely made stone tools.

How Long Did They Stay?

Among the things that are missing from the Gault

site are organic remains, especially charred plant remains.

The preservation conditions are such that so far not a single

charcoal fragment has been found from the lower Paleoindian layers (although many matrix samples

have been saved for further analysis). Charred plant remains

could reveal many important clues and they could be used for

radiocarbon dating. At present there are no radiocarbon assays

of Clovis age from the Gault site. Several

lines of evidence suggest that Clovis peoples visited the

site over a long period of time and may have stayed here for

prolonged periods.

Update: Since the exhibit was created in 2001, the Gault project has obtained a series of infrared stimulated (IRSL) dates from soil samples, a process that can determine when minerals in the soil were last exposed to the sun. The resulting dates nicely match the relative dates indicated by the distinctive artifact styles and give dates of around 13,000 years ago for the Clovis occupations at Gault.

The stratigraphy of the Gault site is very complex.

Because it lies within a narrow stream valley with deep deposits,

permanent springs, and multiple channels coming together,

the character of the deposits can change dramatically over

the space of a few meters (6-10 feet). It was a "dynamic"

environment, meaning that things could and did change quickly.

Major floods, for instance, changed the stream course repeatedly,

ripping up old deposits and creating new ones. As the continuing

excavations connect now-isolated excavation units and as various

geological and soils experts study the many samples that have

already been taken, entire books will probably be written

about the stratigraphy of the Gault site. But based on what

we know today, there are at least three distinct Clovis "components"

at Gault.

That is, in various places in the site there

are at least three distinct layers containing Clovis artifacts.

Their nature implies that these formed over extended periods

of time, decades at least and probably centuries. In the lowest

and hence earliest Clovis deposits, there are the bones of

mammoth, horse, and bison, all species that became extinct

at the end of the last Ice Age. In the later, upper two deposits

the only large bones that have been found are those of extinct

bison. Given this, it is possible that mammoth and horse became

extinct (at least locally) during the Clovis era at Gault.

It is obvious that a considerable period of time elapsed during

the Clovis occupations at Gault, several hundred years at

least and probably more. Based on the IRSL dates,

the Gault site could have been occupied as early as 12,000 B.C. and as late as 10,900 B.C.

Textbooks will tell you that Clovis points were

specifically designed for mammoth hunting. Yet, in the upper

(and latest) Clovis deposits at Gault it appears that no change

in weaponry was made after the extinction of the mammoths.

The Clovis points are still the classic form and they are

found with bison remains. Collins thinks this is another indication

that Clovis technology was a generalized rather than specialized

one. The prevailing concepts are ripe for reconsideration.

This still leaves the question of the nature

of the occupations: were these intermittent, as seems most

likely, or continuous? Researchers aren't sure yet and may

never be certain, but there are indications that the occupation(s)

may have been lengthy. The most obvious is the sheer quantity

of materials and size of the site—this must have taken

either lots of visits or a fair number of people over lengthy

spans of time.

Another clue is the amount of exotic lithic

materials. One of the most characteristic aspects of the stone

tools at most Clovis sites is that the discarded, worn-out-stone

tools are more often than not made of exotic non-local materials.

Many studies have shown that Clovis peoples routinely carried

or traded flint and other stones hundreds of miles from their

sources. But at Gault, exotic materials are very uncommon,

even among the worn-out tools such as Clovis points that were

broken and dulled and resharpened until they were too small

to be useful. Although no counts are yet available, the overwhelming

majority of all stone tools and tool-making materials at Gault

are made of the local flint. This strongly suggests that Gault

hunters commonly started and ended their trips at Gault and

that they did this throughout the history of the site.

Putting It All Together: Clovis Reconsidered

Based on the evidence just reviewed and on arguments

and data presented by many other researchers in recent years,

a new view of Clovis culture is taking hold. Clovis peoples

may not have been the pioneers who first settled North America.

Leaving aside the direct evidence for preClovis sites, there

is this: Clovis artifacts are known from all 48 of the lower

states plus southernmost Canada, Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and northern South America.

These continent-wide localities occupy a tremendous range

of environments, from coastlines to mountains and almost everything

between. The inescapable conclusion from these facts alone

is that most Clovis peoples were NOT highly mobile, specialized

mammoth hunters—they were generalized hunter-gatherers

who must have relied on animals of all sizes and a great many

plants. The emerging data from the Gault site lend very strong

support to this interpretation.

In addition to what has already been mentioned,

here are several more examples of the kinds of evidence from

Gault that reinforce this view. Among the bones found in the

Clovis deposits are turtle bones, burned frog bones, burned

bird bones, and small mammals yet to be identified. In Clovis

faunal assemblages across North America, the most commonly

identified animals are not elephants—they are turtles.

And the Clovis diet was not based on animals alone. This,

of course, is obvious anyway because humans can't live for

long on just meat. But at Gault, use-wear studies are already

finding evidence of a wide range of contact materials including

the stunning example of the Clovis blade with the highly developed

use-wear signature of grass cutting. While grass-cutting may

not have been for food (the tall grasses of the Black Prairie

are ideally suited for thatching and bedding), it is another

indication of the diversity of behaviors that are being documented

at the Gault site.

It should not seem surprising at all that Clovis

peoples were more than one-dimensional. They were, as we are

learning at Gault and elsewhere, much more interesting people

who adapted to a wide range of environments and climates and

behaved like generalized hunters and gatherers of the later

Archaic cultures of North America. Contrast this with Folsom

culture, the quintessential specialized big game hunters of

the Plains. All known Folsom sites occur within or near the

Great Plains and prairies of the midcontinent. And all of

the Folsom sites with animal bones have extinct bison bones.

No Folsom caches are known, suggesting perhaps that Folsom

peoples were so mobile and so focused on "encounter"

hunting strategies, that they did not plan ahead by caching

materials for the future. Folsom peoples did not make much

use of the prismatic blade technology, perhaps because blade

cores are heavy things that don't travel well. The ultra-thin

Folsom bifaces are light and the thinning flakes struck from

them well suited for making Folsom points and other artifacts.

Clovis is anything but Folsom-like.

For now, this is where we leave the story of

Gault and of Clovis reconsidered. Clovis culture will never

be seen again in the same light, as it has for so long. The

Clovis-first hypothesis—with all its implications of

specialized big-game hunters—is all but shattered. While

it hasn't been proved beyond doubt that preClovis peoples

existed in North America, Clovis peoples weren't anything

like those described by the long-held ideal. If they were

the first pioneers, as many archeologists still believe, they

were exceptionally adaptable and extremely fast learners (not

to mention prolific breeders) for whom killing mammoths was

just one of many successful strategies. The results of work

at the Gault site in central Texas will help lead researchers,

students, and the public to a much more sophisticated and

accurate understanding of Clovis culture.

|

Controversies over the peopling of

the Americas have made the cover of Newsweek and have

been featured in many other major media outlets.

|

Gault Project Director Dr. Michael

B. Collins enjoys a pun while introducing TAS volunteers

to Clovis lithics.

|

Gault sits near the head of a small

creek in a small wooded valley just at the point where

three spring-fed brooks come together to form a clear,

cool vigorous stream.

|

The spring-fed creek that winds through

the Gault site has never gone dry in historic times.

In fact, the water table is often so high that the lower

Clovis deposits cannot be reached without continuous

pumping.

|

The deep, well-watered soils of the

stream valley provide habitat for huge hardwood trees—burr

oaks, walnuts, pecans, ash, elm, bois d' arc, and a

dozen more species including willow and cottonwood.

In a word, it is lush.

|

The vegetation in the rolling uplands

of the Lampasas Cut Plain is dominated by oak and juniper;

the latter has increased its density drastically since

the cessation of range fires.

|

A seam of flint nodules is visible

in this limestone outcrop near the Gault site.

|

Nodules of flint from near the Gault

site. The flint at Gault is shiny and gray with distinctive

wispy gray inclusions. In many of the pictures, the

Clovis artifacts look yellow or orange—they are

iron-stained by prolonged contact with iron-rich groundwater.

|

Large Clovis biface, possibly intended

to be further worked into a spear point.

|

Clovis blade cores.

|

Clovis blades and tools made on blades.

|

Incised stones. These may be the

earliest examples of representational art in North America.

Several dozen have now been found including several

that seem to depict animals. Drawn by Pam Headrick.

|

Magnified edge of Clovis Blade with

bright polish so well developed that it can be seen

with the naked eye. This 200x view shows extremely thick

polish and a heavily rounded edge thought to result

from the cutting of grass or similar plants. Photo by

Marilyn Shoberg.

|

Magnified edge of an experimental

blade used for 2000 strokes to cut Little Bluestem grass.

Here the polish is just beginning to form a continuous

band along the edge and the edge is just starting to

round. Photo by Marilyn Shoberg.

|

Mandible (lower jaw) from a young

adult mammoth found at the Gault site. This animal must

have been killed nearby.

|

These heavy, wedge-shaped tools appear

to have been used as choppers or cleavers, perhaps to

dismember large animals.

|

Stratigraphic section at Gault. The

Clovis deposits are in the bottom third of this profile.

|

Clovis point fragment made out of

clear quartz crystal, a material that does not occur

locally. Several quartz crystal flakes found at the

site hint that this unusual material was brought to

the site in a raw or partially worked state.

|

Unfinished Folsom point broken during

manufacture at the Gault site. Only a small Folsom component

has been identified at Gault.

|

|