In this section:

|

| |

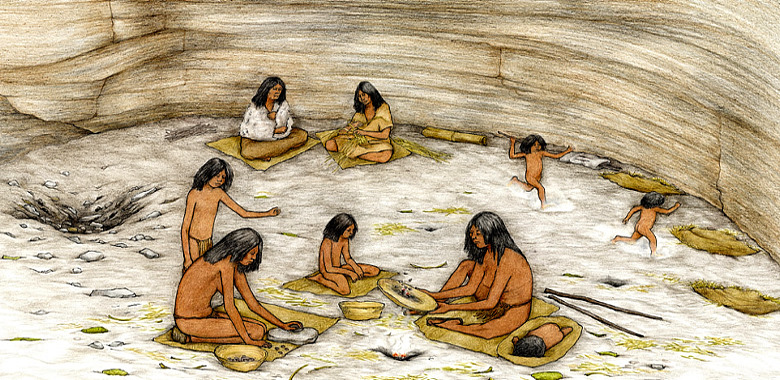

Artist's depiction of ritual life in a Lower Pecos rockhelter. Over the flickering flames of campfire a shaman cast his shadow on the back wall, where rock art murals echo his spiritual journeys. Although the walls of Hinds Cave were too rough for rock art, ritual life must have played out here too, even if archeologists didn't uncover any obvious evidence of it. Painting by George Strickland, courtesy Witte Museum of San Antonio. |

Artist's depiction of a canyon scene in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. The women uses a digging stick as a staff as she makes her way along a rocky tray. Around her head is a woven tumpline leading to the carrying basket on her back. In the background two of her children follow along and help mom on her daily round of gathering. Drawing by George Strickland, courtesy Witte Museum of San Antonio. |

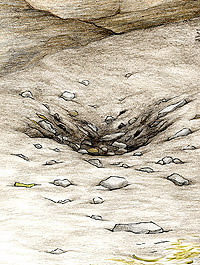

This is what it looks like—a "patty"— but this one was left behind in Hinds Cave by one of its former human inhabitants. Coprolites—dried human feces—represent an extraordinarily direct line of dietary evidence. This specimen is full of fiber, but it looks like it was less than solid when deposited. Such is life. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Artist’s rendering of an evening campfire and meal at a Lower Pecos rockshelter. Painting by George Strickland, courtesy of the Witte Museum.

|

| |

|

Spring snares were among the devices used to trap the small animals that lived in the Hinds Cave canyon. An artifact thought to be part of a share—a once-springy branch and attached thin cord—was found at Hinds Cave. Drawing by George Strickland, courtesy Witte Museum of San Antonio.

|

The remains of a small snare as found in a fiber lens in Area C. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Prickly pear pads were used for food, for packing material in earth ovens, and as floor coverings. The spines have been singed off this specimen and those found in the layer thought to represent an intentional floor covering that may have served mainly to hold down dust. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Excavation dust rises from the mouth of Hinds Cave in 1976. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

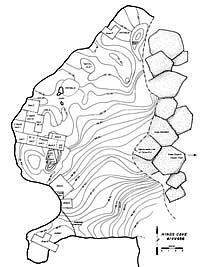

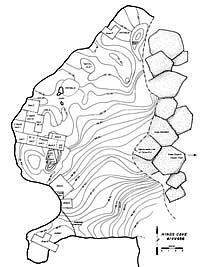

Detailed map of Hinds Cave showing topography, physical

features and excavation areas. The contour interval is 75 centimeters. The

line marked "Approximate Line of Talus Fill" coincides

with the drip line of the shelter overhang. Adapted from Shafer and Bryant

1977. |

Detail of mat woven from sotol leaves. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

.  "Sotol" or earth oven pit. Detail of illustration by Peggy Maceo. |

| |

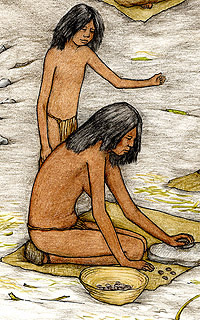

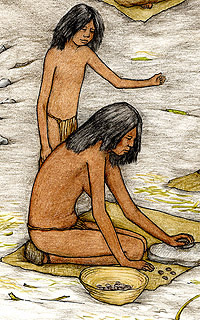

A girl watches and learns as her mother uses grinding stones to crush charred nuts. Detail of illustration by Peggy Maceo. |

Wooden comb with traces of red ochre from the Speck collection, Hinds Cave. It is not known whether this artifact was used for grooming hair or some other purpose. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Hinds Cave has yielded a wealth of potential evidence of seasonality because people brought plant materials and foods into the cave that were available only during certain seasons. |

| |

The fruits of the Texas

persimmon ripen in late summer. This small tree or shrub would have

grown thickly in the canyons. Seasoned persimmon wood is dark and dense, and was used to make digging sticks and other tools. Photo by Phillip Williams. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Mesquite flowers normally appear in spring. The beans (seeds) are ripe in August and September. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Lechuguilla plant with a few outer leaves removed to show the white inner leaf base, the leaf part that is edible. The plant is well armed by spines at the tips of the leaves as well as along the sides, earning the nickname "shinbuster." Photo by Phil Dering. |

|

Here we summarize what has been learned

about daily living at Hinds Cave. Boiling down the

story of 9,000 years of intermittent use of the site leaves us

with a picture of a way of life very different from that which

we enjoy today. Generation after generation of native peoples—all

told at least 350 generations—made their living in the region by hunting and gathering.

Yet, this way of life was not fixed or identical for each group and each period. Researchers are only now beginning to accumulate

enough data to ferret out the finer changes

and trends through time. In the next few decades, archeologists should be able to explore the details and develop

more sophisticated understandings of the ebb and flow of human

life over thousands of years at Hinds Cave and

so many other localities in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Hunter-Gatherer Life

All of the peoples who stayed at Hinds Cave in prehistoric

times lived off the land and followed a nomadic lifestyle known

to anthropologists as hunting and gathering or foraging. Based

on what is known about similar peoples elsewhere,

the basic social group would have been an extended family band of 10 to 25 people. Band members were closely related to one another by kinship ties,

some genetic, some through marriage. Family bands would have consisted of some combination of grandparents,

parents, children, aunts, uncles and cousins.

Related family bands would have periodically joined together in

larger groups of up to 100 people or more on social occasions that

coincided with seasons of abundance, such as the late summer/early

fall ripening of prickly pear tunas, persimmons, and walnuts. Family

bands were related to one another through kinship, shared history,

and language. Anthropologists sometimes call these larger groups

macrobands. Each group, large and small, would have had its own identity, traditional

territory, and unique name, which we—thousands of years later—will never know. Only individual family bands would

have occupied Hinds Cave, but the cave may have been used by several

different family bands who shared partially overlapping territories.

Hunter-gatherer life is highly mobile, especially in environmentally challenging

areas such as the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. People

could not live in one spot for long without exhausting the local supplies

of food and firewood. Instead they must have moved their camps

quite regularly—every few days or weeks—to take advantage

of the resources changing with the seasons and during short-term climatic events. Part of the mobility was tied to seasonal rounds—moving across the landscape to areas

where different food resources could be found in abundance certain

times of the year. For instance, native pecan

trees grew in the deep sediments of the terraces along the

Devils River and other rivers and streams farther east that drain the Edwards Plateau. Pecan nuts ripen

in the fall and are much more abundant in some years than others.

Hunter-gatherers would have monitored the natural crop and planned

for particularly good harvests months in advance. When the season

came, groups would have moved camp to the prime areas.

But the changing seasons only tell part of the mobile lifestyle

story. In the arid Lower Pecos Canyonlands, climatic events can

be extremely localized and must have triggered movements

of people just as they do the movement of certain animals today. As area ranchers

know only too well, warm-season thunderstorms often fall in only

small areas or narrow swaths in this country. When one spot gets

more than its share of rain, plants bloom, shrubs and trees leaf

out, and grasses green up and grow thickly. Deer and other mobile

animals from miles around can move in quickly to take advantage

of localized abundance, especially during droughts and otherwise

tough conditions. Hunters and gatherers would have been equally opportunistic.

The people lived mostly outdoors in open campsites along the river

terraces and in the uplands overlooking the canyons. The main shelter

needed most of the year was simply shade from the intense sun.

This was provided by constructing crude makeshift dwellings and

ramadas (shade arbors) with pole frameworks covered with whatever materials

were at hand: leafy branches, bundles of grass, woven mats, or

hides. We can infer this, paradoxically, from the absence of archeological evidence of

substantial structures and also because brush huts and ramadas were

seen by the early Spanish explorers in the region. Similar makeshift

structures have been documented during more-recent historic encounters

with many native groups living comparable lifestyles in northern

Mexico and the western United States.

When substantive shelter was really needed during wet,

cold, and extremely windy weather, the peoples of the Lower Pecos

Canyonlands could always seek temporary refuge in natural shelters

such as Hinds Cave. Some archeologists think the main occupations

of the dry rockshelters may have occurred during times of inclement

weather. The evidence from

Hinds Cave, however, suggests this particular shelter was used throughout

most of the year, especially during the warm-weather months. Rather than a retreat, Hind Cave probably served more often as a convenient

camping spot for family bands seeking out the resources of

the canyon and nearby landforms.

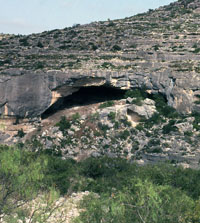

Use of Hinds Cave

We infer that Hind Cave served two principle functions during

most of its use life in prehistoric times—as an occupational

shelter and as a sheltered place to keep firewood, heavy tools like manos and metates, wooden tools, and small caches of food. It was not, however,

occupied permanently or continously throughout the year. Like other caves and

rockshelters in the region, it was used periodically and seasonally

by the bands whose territories included the shelter.

With its large overhang and overall size Hinds Cave did afford

ample protection from rain, although only the small alcove area

(the actual “cave” part) was naturally insulated from

cold and wind. Large rockshelters were more than mere places where

people sometimes lived. Hind Cave and other dry shelters were also

used for dry storage, as caching places for domestic equipment, ritual equipment,

and fuel, as well as final resting places for the dead. And, of

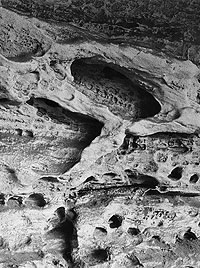

course, the smooth walls of many shelters and overhangs in the

Lower Pecos were used as natural canvases for painted scenes strongly

linked to ritual. Hinds Cave probably served as a ritual setting from time to time, but it has particularly rough, uneven walls that seem never

have to been painted. But it probably served all of the other functions

mentioned above.

There is no reason to think that

Hinds Cave or any other shelter was used for all of these purposes

at any point in time. Although the large shelters must have been

permanent, named places on the human landscape, through the centuries

and millennia they were used to meet many different needs. Outstanding

shelters such as Hinds must have been well mapped into the folklore

and mythology of the people, thereby passing on the cave’s

legacy to each generation.

Like virtually all of the dry shelters in the

Lower Pecos Canyonlands, artifact collectors removed most of the

perishable equipment and burials Hinds Cave once held. Most equipment—mats,

basketry, rabbit nets, digging sticks, grinding stones, and the

like was presumably stored only temporarily between uses, yet over

time things did get left behind. Some things must have been forgotten

or abandoned because they were no longer needed or their condition

deteriorated beyond usefulness. There is also evidence that unrelated

Indian peoples from the Plains moved into the region and displaced

its traditional inhabitants during late prehistoric and early historic

times. Such catastrophic cultural changes must have also led to

abandoned equipment and severed traditions.

We know the dry shelters were used to store equipment and house

burials because many items and some burials were found, documented,

and removed by early museum expeditions and archeological excavations

beginning in the 1930s. Minimal documentation also exists for materials

that some private collectors have donated to museums and for some

materials that archeologists have studied from private

collections.

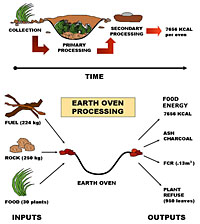

Natural shelters such as Hinds Cave may also have been used to

stockpile firewood in anticipation of periods of wet weather. This suspected habit would have made it possible

to carry out cooking during extended wet periods, especially the use of earth

ovens to bake the hearts of semi-succulants such as lechuguilla

and sotol. Earth oven cooking requires considerable firewood and

probably was most important during the late winter and early spring

when few other foods were available and stored foods were gone.

Cold, wet stretches coinciding with an annual dietary low point

would have made efficient earth oven cooking next to impossible

except in naturally sheltered locations.

Floor coverings. Because the interior of the cave remained dry even in the worst

storm, it was very dusty. No moisture could penetrate the protected

floor and wind erosion of the soft limestone strata from which

the cave is formed created a fine dust layer on the natural floor.

When the natural dust was combined with wood ash from warming and

cooking fires, clouds of dust were created simply by walking across

the floor. To combat this rather inhospitable condition, groups

at different times seem to have covered parts of the floor of the cave with layers of plant materials.

In the Early Archaic, sizable floor sections were covered on two separate occasions with prickly pear pads

with spines removed. At other times,

grasses, and oak leaves were used to cover the floor, perhaps in

hopes of holding down the dust and making the cave more livable.

Living space. The large size of the covered overhang provided living space

and enough work space for the construction of earth ovens.

The steep slope in the front portion of the floor, however, limited

the actual living space. Based on the available floor area of the

relatively flat central rear portion of the shelter and a tiny

space in the alcove, there are perhaps 65-70 square meters (700-750

square feet) of prime space for basic habitation (sleeping, warming

fires, and ordinary cooking fires). It is estimated that Hinds

Cave was occupied by groups of no more than 12 to 15 people

at any one time. More could have crowded in during a bad storm or a

special occasion, but not for long.

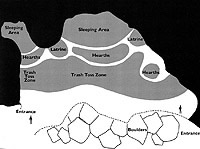

Clues as to the organization of living space have come from excavation observations and specialized analyses. Sleeping areas near

the back of the cave were identified by the presence of beds. These

beds were made by digging shallow pits and lining the bottom with

green boughs (small leafy branches). Woven mats or petate fragments,

prickly pear pads (with spines removed), and discarded sandals

were placed as a padded layer over the bows. Grass was used to

fill the pit and this layer was probably covered by a sleeping

mat when the beds were in use. These beds varied in size, depending

on the size of the person. An adult’s bed measured slightly

more than three feet in length and perhaps two feet across. Why

so small? To conserve body heat, the people who stayed at Hinds

Cave slept in a flexed position, just like many of us do today.

Extensive deposits and lenses of white ash were encountered across

the living areas of the site. We assume some of the white ash was

the result of warming fires allowed to burn and smolder. Placing

warming fires in front of the sleeping area, and heating rocks

to generate heat would certainly help one to survive a wintry night

in Hinds Cave.

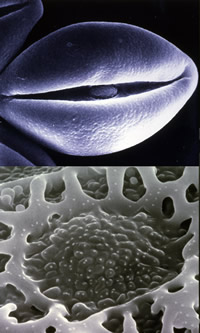

Earth ovens used to bake lechuguilla, sotol, and prickly pear

pads were constructed near the front of the north end of the cave. At least two large burned rock middens and associated

pit ovens were present within the overhang. Other burned rock layers

were encountered in the living area as well. Hinds Cave has some of the earliest evidence for earth oven cooking yet documented

in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Latrine deposits were recorded on the slope along the west wall

west of the main living area. The largest and most permanent latrine

was found on the break of the slope at the front of the living

area (Area B). While an occasional coprolite was recovered in the

living area, there is little doubt that certain areas within the

overhang, but on the edges of the main living space, were set aside

as latrines. The Area B latrine seems to have been used repeatedly

over a several thousand year span during the Early Archaic and

perhaps later.

Clothing and Attire

During much of the year hunting and gathering peoples living in

arid lands have very little need for clothes. They did not have

the same attitude about modesty that most of us do today. Adult

men probably wore simple loin cloths of fiber or leather, and women

wore small apron-like fringe garments or deer skin skirts

and little else. Deer and bison hide garments have been described

historically for hunters and gatherers in central northern Mexico,

but no such garments have ever been recovered in the dry shelters

of the Lower Pecos. Children must have usually gone naked. During

the few cold months of the year (December-February), animal hide

coverings would have been used by all, especially rabbit fur robes.

Rabbit skins were cut into strips and twisted around a fiber cord,

and woven into blankets or robes. Deer and bison hides may have

been used as well, but there was no direct evidence of this at

Hinds Cave.

Few fragments of any kind of clothing were found at Hinds Cave

with one exception: fiber sandals. Worn-out sandals were among

the most common fiber artifacts recovered from the Hinds Cave

excavations. From the dozens and dozens of sandal fragments, we

surmise that everyone big and little wore sandals woven of locally available plants.

Leaves and fiber of yucca and Agave lechuguilla were the preferred

sandal-making materials. Sandal styles changed through time and

one manufacturing technique replaced another with the ebb and flow of human generations.

We do not know the hair styles of the Hinds Cave occupants,

and the styles probably varied through time. Human hair was a valuable

fiber used for nets and textiles throughout the

desert Southwest. Men and women may have used their hair to meet such needs.

Women may have worn their hair cropped or braided, while men’s

style probably varied more widely, depending on the group and time

period. Interestingly, one small wooden atifact with a comb-like working end caked with red ochre

was found at Hinds Cave.

It is very likely some of the Hinds inhabitants were tattooed. Tattooing

was a way of marking social group affiliation and marital status

among desert hunters and gatherers in southern Texas and north-central

Mexico. In earliest historic times, face and body painting was not uncommon among native groups

in the desert, especially when visitors were anticipated. These patterns probably represent traditions that stretch back thousands of years.

Seasonality

It is often very difficult or impossible to accurately determine the time(s) of

year that a prehistoric archeological site was occupied, especially

open campsites with poor preservation conditions. Fortunately,

Hinds Cave has yielded a wealth of potential evidence of seasonality because people

brought plant materials and foods into the cave that were available

only during certain seasons.

The big difficulty in determining

seasonality at Hinds is that desert plants do not respond to

the time of year as much as they do to rainfall. High annual variability in the amount and

timing of rainfall means that plant growth is sporadic. Years can

go by between the appearance of some species and between periods

of abundant growth. For many plants, flowering and fruiting cycles

can occur most anytime between early spring and late fall. Therefore,

precise seasonality determinations are not always possible even

with excellent plant preservation. Analysts

must qualify their seasonality assessments with phrases like “assuming

average conditions.”

Under “normal” conditions wild persimmon fruits,

for example, become available during the late summer (July and August). When abundant

persimmon seeds and fruit parts are recovered from the cave deposits or coprolites,

archeologists assume that late summer is the most likely season the remains

were deposited. Prickly pear fruits from June to September, but may last to October. Mesquite

seed pods ripen in August and September. Walnut and acorns ripen at the close of the warm season, from early

to late fall.

Prickly pear pads

(technically, stems) are available year-around and are not good seasonal indicators. The same is often said about sotol and lechuguilla, but we doubt

this was the case. While it is true that the leaf

bases and “hearts” of mature sotol and lechuguilla

plants can be rendered edible any time of the year, these plants

are marginal food resources even at the best times of the year. That

is, the amount of energy that must be expended to harvest and eat

these plants is almost equal to the amount of energy the cooked

plants yield. Drought stressed plants would have simply not been

worth the trouble. Therefore, it is much more likely that these

plants were mainly harvested during optimal conditions, just prior

to blooming. Normally, these plants bloom in the spring, thus they

are at their nutritional peak in late winter and early spring,

precisely the period when most other plant and animal foods are

scarce or unavailable.

There is another indication that Hinds Cave was sometimes used

during this same, early spring season: the use of live oak leaves

for flooring and possibly for bedding. Live oaks drop their leaves

in advance of flowering and pollinating at the onset of spring

in March. The large quantities of live oak leaves found in

certain Hinds Cave deposits, strongly suggest that this was one

season that the site was occupied.

Taking these factors together, the overall indications of seasonality represented

in the preserved plant materials suggest that Hinds Cave was occupied intermittently

at different times thoughout the year. The strongest seasonal evidence points to

warmer monsoon months from April-October. Late winter-early spring

(February-March) is the logical seasonal peak of lechugilla and sotol baking, of

which there is ample evidence. Definitive evidence

of late fall and winter (November-February) occupation is very hard to recognize. Few resources have seasonal peaks in those lean months when stored foods would have been highly valued.

|

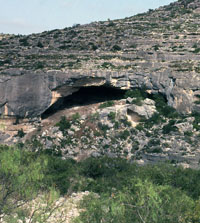

Hinds Cave looking northwest from across the canyon. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

A glancing ray of early morning sunlight highlights the remains of a grass-filled pit thought to represent a child-size sleeping bed. The people who stayed in Hinds Cave slept in the fetus position as evidenced by their small oval beds. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

| |

Family bands were related to one another through kinship, shared history, and language. Anthropologists sometimes call larger groupings macrobands. Each group, large and small, would have had its own identity, traditional territory, and unique name, which we—thousands of years later—will never know. Only individual family bands would have occupied Hinds Cave, but the cave may have been used by several different family bands who shared partially overlapping territories. |

Artist's depiction of a camp in the uplands such as the terrain overlooking the Hinds Cave canyon. The brush shelters may look flimsy, but they were mainly needed to create shade from the intense sun. the woman in the foreground is trimming sotol leaves, perhaps to use them for weaving a new sleeping mat. Painting by George Strickland, courtesy Witte Museum of San Antonio.

|

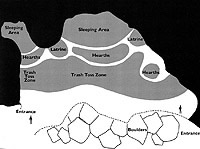

Schematic drawing showing an idealized model of how the living space in Hinds Cave was used by Early Archaic peoples. Image courtesy of the Witte Museum.

|

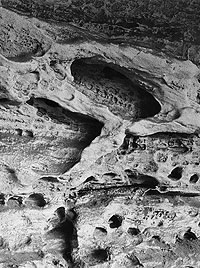

The limestone wall of Hinds Cave is pitted and uneven, totally unsuited for the vivid rock art found on the smooth walls of many dry rockshelters. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Artist's depiction of a woman morning the loss of her infant, who is wrapped in finely woven mats. An infant burial is said to have been found by a collector at Hinds Cave. Fragments of the mat wrap were radiocarbon dated to about 200 B.C. Drawing by George Strickland, courtesy Witte Museum of San Antonio.

|

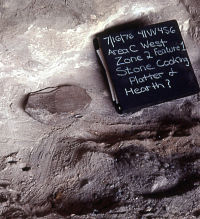

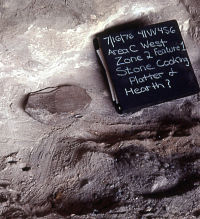

A small flat stone found in association with ash and charcoal may have been used as a griddle, or heated stone used for cooking. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

| |

Natural shelters such as Hinds Cave may also have been used to stockpile or cache firewood to be used when periods of wet weather would set in. This suspected habit would have made it possible to carry out cooking during extended wet periods, especially earth ovens to bake the hearts of semi-succulants such as lechuguilla and sotol. |

Artist's rendering of a child playing inside Hinds Cave. The material culture of children is often ignored by archeologists, but children added significantly to, and probably disturbed, the archeological record. Drawing by Peggy Maceo. |

Grass layer representing a sleeping bed exposed in trench wall. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

The flat, thin lenses seen most clearly on the left side of this close-up photograph are layer after layer of urine-compacted soil. The dark and light bands represent ash, charcoal and other living debris compacted by the repeated use of this area of the shelter as a latrine.This photo, taken late in the 1976 season, depicts the lower deposits in the south wall of Block B as exposed during the excavation of the north half of the block. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

| |

Worn-out sandals were often recycled as padding for sleeping beds. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Sandals were perhaps the most essential item of clothing for native peoples living in the rough terrain of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Drawing by George Strickland, courtesy of the Witte Museum. |

| |

Below freezing temperatures, such as occurred on the winter day this photo was taken, reminds us that people had to survive year-round in the seemingly harsh environment of the Lower Pecos with only what nature and their own technology could provide. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Ripe tunas. Prickly pear fruit, known as tunas or pears, begins to ripen in late summer to a deep red color and produces a very sweet, yet otherwise tasteless, purple-red juice. The tunas are eaten by many animals as well as people.

|

Cooked lechuguilla. Properly prepared, the lower leaves and the central stalk are sugary sweet and no longer contain toxins and soapy compounds. The taste is intensely sweet and a bit smoky. Photo by Phil Dering.

|

|