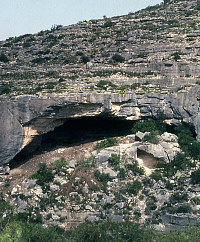

Hinds Cave as it looked in 1974 during the archeologist's first visit to the site. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

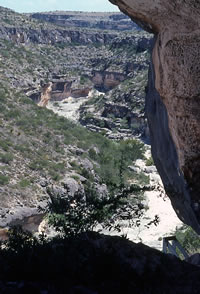

View down the side canyon in its normal bone-dry condition today. This photo was taken from Hinds Cave in the summer of 1976. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Winter fog hangs over the canyons near Hinds Cave, which is just visible on the canyon wall near the center of this 1980 photo. Note the eroded rocky terrain in the foreground and the scar of a ranch road. The upland edges were said to be covered in enough soil early in the 20th century so horseback travel was practical. In fact, there was enough grass then to support horse and cattle grazing. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

The fruits of the Texas persimmon ripen in late summer. This small tree or shrub would have grown thickly in the canyons. Seasoned persimmon wood is a dark, dense hardwood, and was used as to make digging sticks and other tools. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Swallows nest on the ceiling of Hinds Cave. These birds migrate south in the fall and return in the spring. Photo by Phil Williams. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

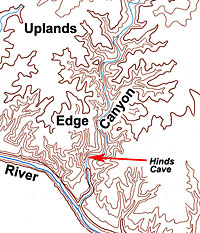

This topographic map shows

the location of Hinds Cave relative to the four environmental

zones: uplands, edge, canyon, and river.

|

This banded rock rattlesnake reluctantly retreated from Hinds Cave when the archeologists arrived each summer. Although most of us consider rattlesnakes dangerous because of their poisonous venom, the native peoples who stayed at Hinds Cave may have considered them food resources. The bones of the rock rattlesnake and three other species of rattlesnakes were tentatively identified from the Hinds Cave deposits. Snake vertebrae were also found in several coprolites. Photo by Phil Williams. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

The Blue Hills, a low set of hills within the high uplands about 20 miles north of Hinds Cave. This area lies within the high divide between the Devils and Pecos rivers and appears to have been used mainly by hunting parties. Photo by Joe Saunders.

|

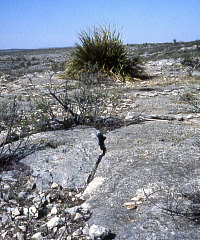

Bedrock surface on the upland-canyon edge on the Hinds Ranch. As recently as the early 20th century there was still enough soil present along the canyon edge to make horseback riding possible. Today these surfaces are largely denuded, a process which sometimes brings archeological evidence to light. In the foreground are several stone tools classified as "formal unifaces" that functioned as knives for trimming plants such the clumped up sotol visible in the background. Photo by Joe Saunders.

|

| |

|

The old idea that people lived year round in the shelters, as more or less permanent base camps, is seen today as unrealistic. If even a small band of hunter-gatherers lived for long in one spot in one small canyon, they would quickly exhaust the easy-to-eat foods and burn up all the easy-to-harvest firewood.

|

| |

A pool of water along the Pecos River near Hinds Cave. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Like many other items found in Hinds Cave, this mussel shell suggests that people went to and fro between the cave and the river on a regular basis. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

|

Hinds Cave occupies a classic Lower

Pecos Canyonlands setting—a narrow side canyon off the lower

Pecos River some 20 miles above where that river

joins the larger and even more deeply incised Rio Grande. The generations

and generations of native peoples who lived

here led physically demanding lives climbing in and out

of the canyons and trekking across the twisting and turning terrain

on daily rounds. While the dry rockshelters that preserved so much

material evidence of ancient life continue to dominate our perception of their

lives, prehistoric peoples must have spent as much or more time in the rolling

uplands. To understand

the natural setting of Hinds Cave, one must consider the ecology

and physical constraints of the wider landscape as well as that

of the small, sheltering canyon that houses the site.

The cave is tucked the side of a

limestone canyon less than

a mile from the Pecos River. Today the narrow canyon is dry

except for short periods following heavy rains. The canyon

floor below the site is fairly level and the lower canyon walls

are only about 20 meters (65 feet) apart. The east wall of the

canyon slopes away from the center of the canyon, while the west

wall containing Hinds Cave rises almost vertically for some 30

to 40 meters (100-130 feet). The limestone bedrock that forms the

canyon floor is strewn with large rounded boulders and pitted with

shallow pothole depressions known as tinajas that

can hold water for days, weeks or even months following heavy rains. These shallow, temporary pools are a

boon to wildlife, as they must have been to the native

peoples who stopped at Hinds Cave.

Shelter

Technically, Hinds Cave is a rockshelter because it is much wider

(37 meters or 121 feet) than it is deep (23 meters or 75 feet). The small alcove at one end of the shelter is a true cave, but not much of one. Hinds Cave formed as a large solution cavity deep within in the Cretaceous limestone

bedrock that was gradually bisected and exposed by canyon-cutting

floodwaters and further shaped by eroding winds. These active geological

processes did most of their work over long spans of geological

time, tens of thousands of years before humans arrived on the scene. The

cavity has a high limestone ceiling and is quite typical of the

dry “caves” of the region except for its larger than

average size.

Hinds Cave is high and very, very dry—perhaps 99% of its deposits are bone dry and have remained so for thousands of years because of the large overhang of the roof. Even blowing rains scarcely penetrate the dusty

dry cave. There is evidence of minor seepage along the rear wall

of the shelter that fostered the growth of tiny white crystals

in rock fissures. This seepage pales by comparison to the active

springs that issue forth from the cracked walls of some shelters,

particularly those that lie deep in the main canyons.

The entrance to the shelter is about 20 meters (66 feet) above the canyon floor

and can be reached by one of two ways. From the bottom of the canyon,

the fastest route is a nearly vertical climb up the rugged cliff

face. From the uplands or from farther up the canyon, the best

approach begins at the mouth of an even smaller tributary canyon

that is more or less level with Hinds Cave. Following topographic

lines, the visitor must slither across the sheer rock on tiny ledges

loved only by sure-footed goats. Either way, access to Hinds Cave

is physically and psychologically demanding and that may have afforded

some protection to those who stayed here in troubled times past.

Hinds Cave faces northeast. Summer conditions in the shelter are hot, still, and sunny in

the early morning, and shady and breezy (if incredibly dusty) throughout

the rest of the day. It is undoubtedly the coolest afternoon spot

in the immediate area unless you are immersed in the Pecos River.

Space inside the shelter during both summer excavation seasons

had to be shared with rock rattlesnakes, scorpions, canyon wrens,

digging wasps, earth-moving bumblebees, and small bats. In the

winter it is a less

inviting place, and wildlife is gone from inside the shelter. Although temperatures remain fairly constant in

the tight confines of the protected alcove, the main body of the

shelter is cold and open to chilling winter breezes which blow occasionally

from both directions in the side canyon. That is, north to northwest

winds whip down the canyon while northeast to east winds seem to

flow up the canyon. Either way, the shelter’s usefulness

as a refuge from bitter winter winds in prehistoric times would

have been limited—there are far better situated rockshelters

elsewhere in the canyonlands.

Landscape

One can picture the local landscape around Hinds Cave as having

four major ecological zones or topographic layers. From higher to lower in the landscape these are the uplands, the edge,

the canyon, and the river. These

layers or zones framed the daily lives of the people who frequented

Hinds Cave. From the shelter an agile teenager, for instance, could quickly

move up slope and explore the upland-canyon edge and follow the

slope up to the high uplands which stretch for many miles. Or our teenager

could scamper down the steep face into the narrow confines of the

canyon. From there, in less than an hour she could walk down the

canyon floor, hop a few boulders, and follow the dry stream bed

as it “flows” down step-like bedrock layers and reach

the banks of the Pecos River.

These four zones had (and still have) only partially overlapping

sets of natural resources useful to humans—plants, animals,

rocks, and water. For instance, if you wanted fish to eat, like

one of the eight species whose bones were found in Hinds Cave,

you had to go down to the river. Likewise, if you wanted to find

a thick stand of sotol, your best bet would be on the steep rocky

slopes of the upland-canyon edge. Walnut trees favored the

sheltered side canyons, and antelope could only be found in the

high uplands. This is a bit simplified, but the major patterns

and zones are quite real, and all Hinds Cave denizens would have

known these like the backs of their weathered hands.

The distinctive ecological characteristics of the four zones

are caused by underlying factors— terrain, geology,

soils, and water—that govern the distribution of natural

resources. Briefly, let’s consider each zone, starting at

the top.

The Uplands are broad expanses of essentially

the same limestone plateaus that stretch east and north all the

way to Austin and beyond. Nearest Hinds Cave, the uplands are sloped

and irregular near the canyon fingers and flatten out on the divides.

The high divides between the major river systems can be almost

flat and unbroken. Within the uplands are low hills such as the

Blue Hills that lie about 20 miles north of Hinds Cave on the

divide between the Pecos and Devils rivers. The uplands are typically

dry and have very little natural surface water except right

after rain along major draws.

Today much of the uplands are extremely rocky and rough with hardly

any soil and, as a consequence, relatively few remaining native

grasses. This is mainly a sad fact of modern history. Beginning

in the late 19th century, Val Verde County was heavily overgrazed

by livestock (cattle and then sheep and goats), denuding the grass

cover. After decades of grazing stress, the prolonged drought of the 1950s reduced grass cover to almost nothing. Then came the famed 1954 flood, the magnitude of which has been estimated to occur once every 2,000 years (or less often). Without grass to anchor the soil, it washed away in a mere blink of

geological time. It was an environmental disaster that permanently marred the landscape.

Only a century ago, visitors found the uplands

much more hospitable. Soils were thin, but they covered most of

the flatter bedrock expanses and supported an arid savannah—a

mix of grass, brush and stunted trees. In the flat uplands, far

away from the edges where there was more soil and more grasses

and low trees, deer browsed regularly as did antelope and, during

a few unusually wet periods when grasses grew thickly, bison. Male

hunters probably roamed great distances over the uplands in search

of large game. The distant uplands were, however, poor places to

find water or shelter most of the time and no one stayed there

for long. This was not place to live or camp for long (residential zone).

The Edge is a transitional zone between the high

uplands and the canyons. The terrain is sloping and rough, especially along

the canyon rims, because there is little or no soil and lots of

loose, sharp limestone rocks that have broken loose from the limestone

bedrock. The upland-canyon edge provides several types of rocks

used as raw materials. For instance, outcrops of chert (“flint”)

nodules are exposed along the canyon edge not far from Hinds Cave.

It is likely that limestone slabs and chunks used as cooking

stones were often collected along the edge. Limestone rocks

are common in the canyon, but it would have been a lot easier to carry rocks

down into the cave than to lug them up the steep canyon walls.

The eroded edges of the uplands probably never had enough soil to support

thick grasses. Instead this is where many arid-adapted species

such as prickly pear cactus, sotol, and lechuguilla grew in thick

stands. These stands were very important resources visited regularly

by Hinds Cave peoples. We know this because there are many campsites

on the edges of the uplands and many burned rock middens where

plants were baked. In fact, archeologists believe that the

upland edges were important residential zones. Here people could

spread out and stay comfortably near to the many resources found

in the canyons below.

The side Canyon that houses Hinds Cave was also

a residential zone, albeit one used only sporadically during the warm months of the year. It may have also served as a convenient place to duck into during times when a naturally roofed and shaded house or a hidden spot was needed.

Hinds Cave is one of many side-canyon rockshelters that people

occupied in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. But the old idea that

people lived year round in the shelters, as more or less permanent

base camps, is seen today as unrealistic. If even a small

band of hunter-gatherers lived for long in one spot in one small

canyon, they would quickly exhaust the easy-to-eat foods and burn

up all the easy-to-harvest firewood.

Our best guess today is that rockshelters were occasional stopping

places that were visited seasonally for a few days or weeks and

perhaps somewhat more frequently for temporary overnight shelter

from storms and as convenient stopovers during short excursions

into the canyons.

The side canyons did have many useful resources, beginning with

water. While the canyon containing Hinds Cave is dry today, its

tinajas (potholes) can hold water for weeks. As recently as 1953,

the canyon floor was a wetter place with a lot more soil and vegetation.

The famed 1954 flood, estimated to represent a 2000-year flood, was simply the final

nail sealing a coffin built by long-term overgrazing and soil erosion.

According to rancher Carrol Hinds, the narrow canyon bottoms were half "covered with rich bottom soil” before they were stripped

to bedrock and filled with gravel. Prior to being scoured out,

the side canyons were thickly vegetated by trees, brush, and vines, including

many species, such as little black walnut trees and mustang grapevines,

rarely found in the uplands.

The Pecos River and its alluvium-filled valley

was a major resource zone and must have also served seasonally

as a major residential zone. Carrol Hinds described the valley in the

early 20th century as a more productive area than it is today.

The river “ran between two strips of rich sandy loam that

was mostly covered with …grasses along with … high

weeds … [and] very few trees.” Trees were present but

weren’t as thick or as diverse as those in the protected

side canyons. Today the valley has been stripped of some of its

rich alluvium and choked with invading species of trees such as

salt cedar, but the river is still an inviting place to kayakers, fishermen,

and swimmers.

For hunting and gathering peoples of the past, the Pecos River

was a unique and bountiful resource. In the Hinds Cave archeological

record the most obvious riverine elements are the bones of many fish

and other aquatic species including mussels (freshwater clams), soft-shell

turtles, and frogs. Clearly, people went between Hinds

Cave and the river on a regular basis. The lower river valleys of the Devils and Pecos Rivers within the area now covered by Amistad Reservoir were major residential settlement zones.

The degree to which the Pecos River

valley nearest the site was also a residential zone is somewhat difficult to evaluate

as not much archeological research has been done directly along its

banks near Hinds Cave. Given the known magnitude of major floods

in historic times—the Pecos River at the mouth of Lewis Canyon

crested at 103 feet above its normal level in the 1954 flood—many

sediment layers where past evidence would have been concentrated

may not survive. Flood cycles, of course, occurred many times in

the past, a factor that native peoples would have been well

aware of.

|

Archeology students head down into the steep rugged canyon below Hinds Cave. This was said to be the "easy" route. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

The side canyon in flood below Hinds Cave, a rare event immediately following a heavy overnight thunderstorm. Today the canyon floor is mostly bedrock and gravel, but less than a century ago it was covered with soil and thick tangles of trees, brush, and vines. Overgrazing reduced the vegetation and allowed floods to scour out the bottom of the canyon. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Ceniza flowers color the uplands purple when rains come. In this 1975 picture the eroded rocky condition of land is obvious. A century earlier the uplands had much more soil and grass. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Sotol and yucca (on right) growing on the canyon rim near Hinds Cave. Sotol (Dasylirion) usually blooms in the spring, but in dry years it waits for rain and blooms when it can. Sotol was a very useful resource. Its strong leaves were trimmed of their thorns (or not) and used to weave mats or separated into fibers for making cord and sandal straps. Its dried stalk was used as a lightweight wood and as fuel. And its leaf base or heart was baked and eaten, especially during the Late Archaic period at Hinds Cave. Yucca was valued mainly as a source of tough fibers that come with a built-in needle (the thorn tip). TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

A small cluster of bats occupied a narrow cavity in the ceiling of Hinds Cave during the warmer months. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

"In the higher land were small pockets or areas of deeper soil that has been eroded away but the larger and more level spots of deeper soil is still intact to a great extent except where man has added permanent water or other changes that had a tendency to cause a greater concentration of livestock. In that case in most instances erosion of top soil has been extensive."

-Carrol W. Hinds

Excerpt from 1977 letter.

Read more.... |

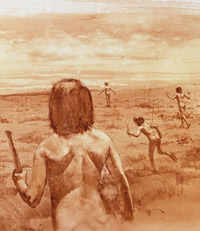

Artist's reconstruction of a rabbit hunting scene in the uplands. Artwork by George Strickland, image courtesy of the Witte Museum. |

Broken chert nodules visible in the foreground represent one of the resources that drew hunter-gatherers to the upland edges. Photo by Joe Saunders.

|

View looking northwest at Hinds Cave from the upland edge. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Although stripped of much soil, the side canyons still provide shelter and habitat for trees, shrubs, and vines that cannot thrive or even survive in the uplands. Here a flower blooms in the shade of persimmon trees. Photo by Phil Williams. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

View of the canyon bottom looking down from Hinds Cave. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

The Pecos River near Hinds Cave. Photo by Joe Saunders.

|

|