"I was stunned by the beauty of the workmanship.

The hair on the nape of my neck bristled erect. I had

never seen anything like it, and instinctively knew

it was special."

—Gene Mear, on finding a 12,000-year-old fluted

Folsom point while screening backdirt at Kincaid Shelter

in the late 1940s.

From "All Things Considered, It was Fun While It

Lasted," a small volume in which Mear recounts, among

other experiences, how his work at the site changed

the direction of his life from studies in chemistry

to a career in geology.

|

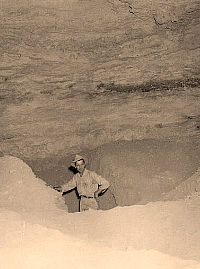

Gene Mear looks over a trench dug

through the shelter by the TMM . The young college student's

discovery of three Folsom points in the shelter is what

triggered the chain of events leading to systematic

investigations of the site. Photo by Glen Evans.

|

Map of TMM excavated units (marked

with dots) and location of treasure-hunters' pits (denoted

with horizontal lines) in Kincaid Shelter, as drawn

by Glen Evans. Click to enlarge and read key.

|

|

Only a small area of the surface deposit within

the shelter remained undisturbed, but fortunately there

had been comparatively little disturbance in the deeper

zones and in front of the shelter.

|

A crew member holds a screen over a wheelbarrow in front of the shelter where it will be filled with

another load of dirt. All sediments from the shelter

were screened for artifacts and then hauled to a dump

site below. TARL archives. Click to see full image.

|

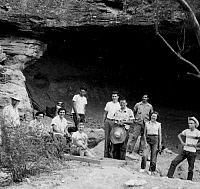

Visitors pose in front of the field

camp tents with crew member Powell Goodwin, right, during

the 1948 investigations at the site. TARL archives.

|

Hard day at the shelter. University

of Texas field school students take a break from excavations

during the 1953 project at Kincaid. The woman sporting

the horned-rimmed glasses, in center, is Dee Ann Suhm,

who went on to become a professor at UT-Austin, director

of TARL, and author of numerous landmark publications

on Texas archeology.

|

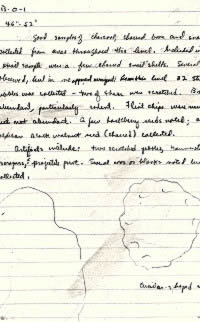

A page of field notes written by then-student Dee Ann Suhm at the U. T. field school at Kincaid in 1953. The young student's careful attention to detail was evident even then.

|

|

In December of 1947 while hunting on the Kincaid

Ranch, young college student Gene Mear and several of his

friends visited a rockshelter in a low, limestone bluff on

the Sabinal River. They examined some loosely piled-up dirt

that had been thrown out of a pit dug in the shelter fill

and found several flint artifacts and burned bone fragments.

His curiosity and latent geological instincts

aroused, Mear returned to the site several times, usually

accompanied by Kenneth Rochat, and screened quantities of

the loose, disturbed fill in the shelter. His labors paid

off: among the items he recovered was a complete, exquisitely

made Folsom point. "I was stunned by the beauty of the

workmanship. The hair on the back of my neck bristled erect.

I had never seen anything like it, and instinctively knew

it was something special."

After finding two additional Folsom points,

Mear reported his finds to Ellen Quillin, director of the

Witte Memorial Museum in San Antonio, and she, in turn, reported

the discovery to Glen Evans of the Texas Memorial Museum.

An experienced geologist who had also investigated

several important "early man" sites, Evans was excited

about the site's potential significance. Roughly 20 years

earlier in 1927 at Folsom, New Mexico, the same type of thin,

fluted projectile points had been discovered embedded in the

bones of extinct bison. Prior to that time, it was believed

that the first cultures in America were no more than several

thousand years old. The New Mexico discovery revolutionized

perceptions about the peopling of North America, pushing estimates

of the time of first migrations back into the Late Pleistocene.

In September 1948, Evans accompanied Mear to

Uvalde County to see the shelter, and the two cleaned off

a wall section of fill exposed in one of the old pits. The

shelter deposits were seen to be stratified (layered), with

bones of extinct animal species in place in the lower deposits

and cultural materials associated with bones of modern animals

in the upper layers. The possibility of gaining important

new information was obvious, and plans for excavation immediately

were initiated.

Controlled Excavations Begin

Excavation at the Kincaid site was done in two

stages. The first stage, in the fall of 1948, was sponsored

by the Texas Memorial Museum (TMM) and was directed by geologists

Sellards and Evans. During this first stage of excavation

most of the shelter deposits were removed down to the culturally

sterile fill near the bottom of the shelter, and deep trenches

dug in the terrace deposits in front of the shelter.

Before systematic investigations were underway,

Evans and the TMM crew evaluated the extent of disturbances

to the shelter fill. Several large pits had been dug inside

and near the shelter. In addition to the deepest of these

old pits and trenches, there were numerous smaller areas where

the fill had been dug into and otherwise disturbed. Only a

small area of the surface remained in its original position

but, fortunately, there had been somewhat less disturbance

in the deeper zones and in front of the shelter.

From people living in the area it was learned

that the pits and holes had been dug by "treasure hunters,"

men who were down on their luck and hoping for a change in

fortune. Hit hard by the Great Depression of the 1930s, they

hoped to find some of the legendary treasures described in

books by J. Frank Dobie and other authors.

Evaluating the damage, Evans saw that other

forces also had taken a toll on the shelter deposits. Small

rodents had burrowed into the shelter fill. There were also

larger burrows, probably made by badgers or coyotes digging

into the rodent dens. Some of the larger burrows had collapsed,

causing overlying deposits to be displaced. In some of the

open burrows, materials obviously belonging in the uppermost

layer had filtered down into lower layers or deposits. Roots

from brush and small trees growing on the slope in front of

the shelter had worked their way inside, causing considerable

disturbance, particularly in the upper two feet of deposits.

The first step for investigators was to remove

the old waste heaps and other disturbed materials in order

to minimize the danger of mixing artifacts and faunal remains

belonging in different stratigraphic layers, or zones. The

disturbed sediment was hauled out of the shelter in wheelbarrows

and passed through screens to salvage artifacts and bones.

The process of clearing out debris required more than two

weeks. After the debris had been removed from the shelter,

the entire surface of the undisturbed fill was painstakingly

swept clean with whisk brooms.

With a more-level floor in front of them, Evans

and his crew laid out a grid system made up of six-foot squares

across the undisturbed shelter fill. In order to be able to

study the stratigraphic relationships between deposits inside

and outside the shelter, they first dug contiguous rows of

successive squares to form long trenches, extending from the

back wall of the shelter. The two principal trenches thus

developed were between lines B-C and A-C, as shown on the

grid map above, left.

The crew then excavated the remaining squares

and plotted cross-section profiles. When possible, each square

was excavated in six-inch (15 cm) vertical cuts, or levels,

but thicker cuts were made at some places where large boulders,

tree roots, or burrows made the usual six-inch cuts impractical.

Excavated material was screened, typically through one-quarter

inch screens; artifacts were logged by provenience (location);

and sediments were hauled out of the shelter to a spoils dump

area.

The TMM crew succeeded in investigating and documenting

most of the shelter deposits, with the exception of several

units near the back where ancient travertine had hardened

and cemented the fill. The workers completely removed the

ancient stone pavement and excavated the underlying zones

to near bedrock in several areas. A section of fill near the

front of the shelter was left in place as a "witness

column" to preserve a record of the stratigraphy for

future investigators. Artifacts, animal bones, a sample of

paving stones, and field records were packed up and brought

back to Austin for analysis.

U.T. Students Join the Effort

Five years later, during the heat of summer,

the second stage of excavation got underway at Kincaid. Led

by anthropology professor T. N. Campbell, the effort was jointly

sponsored by the Texas Memorial Museum and the Department

of Anthropology of the University of Texas. Unlike the previous

work, the project was conducted as a summer field school to

train college students in archeological methods and techniques.

During the field school, the remainder of the

culture-bearing deposits of the shelter were removed, further

excavation was done in the terrace deposits in front of the

shelter, and five test excavations were made in the terrace

deposits under small bluff overhangs immediately east and

west of the main shelter.

Among the field school students was a young woman

destined to become a major figure in Texas archeology. Dee

Ann Suhm (later Story) received her basic training at Kincaid,

went on on to earn a Ph.D in anthropology, teach at the University

of Texas, and become the director of the Texas Archeological

Research Laboratory. Her field notes from Kincaid reflect,

even then, a careful eye for detail that she used effectively

in writing landmark publications such as An Introductory

Handbook to Texas Archeology, published in 1954 with Edward

Jelks and Alex Krieger.

Over the course of roughly four months of excavations during

the two field projects, a total of 55 squares were dug.

All collected artifacts were assigned numbers according

to their provenience, including a generic lot number to designate

materials found out of their original context. Evans estimates

that at least half of the artifacts were from the disturbed

fill, or backdirt scooped out and left in piles by the treasure

seekers.

A Voice from Beyond

While excavating the site in 1948, Evans remembers

having a brush with a furtive individual who, unbeknown to

the crew, was watching over the procedures.

He recalls: "I was digging a profile out

in front of the shelter when I heard a low voice saying, 'You're

diggin' in the wrong place.' It was one of the local people,

hidden in the brush—likely one of the people who had

dug at the site seeking treasure. But it was clear he wasn't

prepared to show me what he thought was the right place."

And of course, Evans notes, the true treasure

at Kincaid was very different than what the strange man was

after.

|

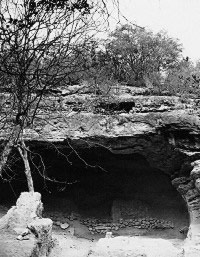

Backdirt piles left by treasure hunters

can be seen mounded in the front of the shelter (bottom

right ) after TMM investigators cleared away brush.

TARL archives. Click to see full image.

Click images to enlarge

|

Books such as J. Frank Dobie's Apache

Gold and Yaqui Silver, published in 1939, inspired treasure

hunters to dig for legendary riches in area caves and

shelters such as Kincaid. Original Tom Lea cover art

and frontspiece courtesy of Mrs. Tom Lea and the University

of Texas Harry Ransom Center, Dobie Collection.

|

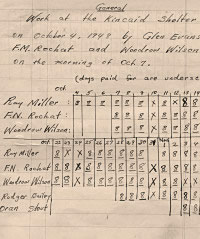

Work log and payroll (click to enlarge)

from Glen Evans' notes lists the small start-up crew

for the TMM project (including an individual named Woodrow

Wilson, presumably not related to the former U.S. president).

Paleontologist Grayson E. Meade was among those added

to the crew, and anthropologists Thomas N. Campbell,

Alex Krieger, and J. Charles Kelley were frequent visitors

to the site during TMM excavations. TARL archives.

|

|

Prior to the 1927 Folsom discovery in New Mexico,

it was believed that the first cultures in America were

no more than several thousand years old. That find revolutionized

perceptions about the peopling of North America, pushing

estimates of the time of first migrations back into

the Late Pleistocene.

|

Geologist Glen Evans stands in one

of the large pits left by treasure hunters inside the

shelter. Evans directed Texas Memorial Museum field

work at the site. TARL archives. Click to see full image.

|

Stones from the pavement, shown lined

up across the front of the shelter, were removed after

documentation so that the investigators could excavate

the layers beneath them. The small tree at left marks

the location of the "witness column" left

in place by TMM crews to preserve a record of the stratigraphy.

TARL archives.

|

The University of Texas Field School

crew, headed by anthropology professor Thomas N. Campbell

(left), poses in front of the shelter before beginning

excavations in 1953. The field school dug the remaining

shelter fill and excavated sections of the terrace in

front of the shelter. TARL archives. Click for more

detail.

|

Glen Evans, shown in trench in front

of the shelter. One day while working, Evans heard a

voice from the underbrush nearby, telling him that he

was digging in the "wrong place." |

|