|

Over the millennia, hundreds of people

stayed in Kincaid Shelter, using the protected locale

as a base for hunting animals, gathering plants, nuts

and seeds, making tools, refurbishing gear, and carrying

out other tasks of daily life. Others may have merely

stopped there overnight during a longer journey. Like

their modern counterparts, many of these prehistoric

campers left behind a scattering of trash as well as

a few more meaningful items that perhaps were lost or

forgotten in the shelter's recesses.

Yet what was trash to prehistoric and

later peoples often holds special significance to researchers

today. Even broken or spent weapons carry important

technological and stylistic information which helps

researchers understand life in the past. Discarded tools

and toolmaking debris provide insights into the technologies

and economies of the various prehistoric visitors. Animal

bones inform researchers about the prehistoric diet

and may indicate changes in climate and the environment

over time.

Unfortunately more than half of the artifacts

recovered from Kincaid have no precise provenience,

that is, they were out of place, having been dug up

and discarded by treasure-hunters. Since the diggers

were searching for gold and silver, they left the Indian

artifacts behind in their backdirt piles. Prehistoric

peoples churned the shelter deposits as well, perhaps

digging pits into lower levels for hearths and, in the

process, displacing and mixing items left by earlier

visitors. For these reasons, many of the items from

the shelter cannot be connected to a particular cultural

group or time period.

In this section we present a gallery of

selected artifacts from Kincaid Shelter curated in the

TARL Collections. While investigators did not collect

or document all the items they encountered, as is the

more standard practice today, they did recover a meaningful

sample that provides a window into past activities and

peoples at Kincaid. The artifacts have yet to be fully

analyzed and reported, although T. N. Campbell did a

preliminary classification as part of an unpublished

report on Kincaid. Michael Collins and Gene Mear inventoried

and measured many of the chipped stone items in the

collection, and Collins did a more in-depth study of

the Paleoindian materials. Parts of these data are used

in descriptions below and in the Kincaid

Revisited section, which details Collins findings.

Weapons and Tools

|

|

In This Section:

|

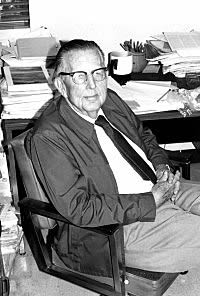

The late T.N. Campbell, professor

of anthropology at the University of Texas at

Austin, classified most of the Kincaid artifact

collection and, with Glen Evans, wrote up the

findings from the site. The report was never completed

or published. Archeologist Mike Collins, working

with Gene Mear, took over the effort in 1988.

Collins took this photo.

|

| |

|

|

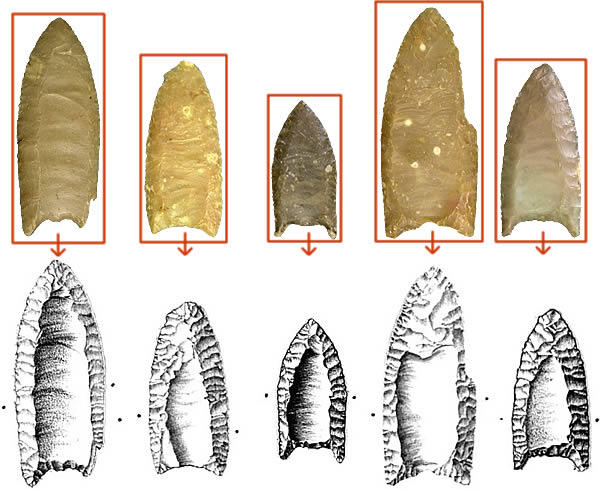

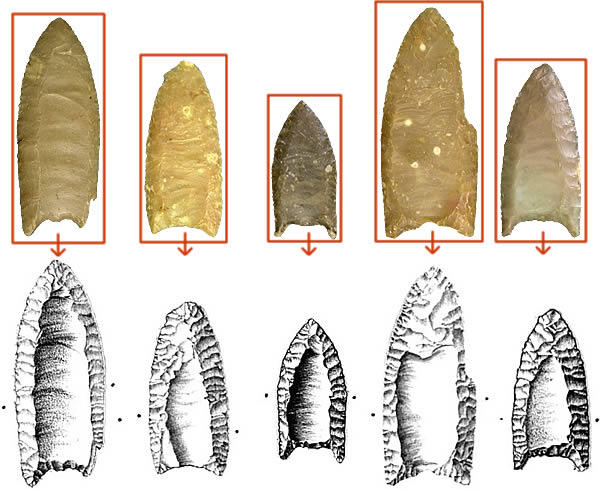

Five Folsom points were recovered from

treasure hunters' backdirt piles at Kincaid. The fluted

points are a distinctive "signature" of the Folsom culture,

bison-hunters and gatherers who roamed the North American

Plains roughly 12,000 years ago. Dots on drawings indicate

extent of grinding on lateral edges (from the bases). TARL

Collections. Photos by Aaron Norment; drawings by Hal Story.

Click on photos to enlarge and see reverse views.

|

|

A resharpened point

found in a backfill pile. Its tip is partially coated

with travertine (calcium carbonate), indicating it originally

derived from Late Pleistocene deposits. The flutes on

both faces (sides) were from multiple blows. Collins

has identified it as a Clovis point . Photo by Aaron

Norment.

|

This fragmentary Paleoindian

point base is made of a particular type of obsidian

which occurs only in Querétaro, Mexico, more

than 600 miles to the south. It was found in the Clovis-era,

Zone 4 deposits. It cannot be confidently assigned to

a particular point type, although it bears some similarities

and presumed affinities to Clovis. The right corner

was removed for sourcing analysis. Click to enlarge

and see drawings of unaltered specimen. Photo by Araon

Norment.

Click images to enlarge

|

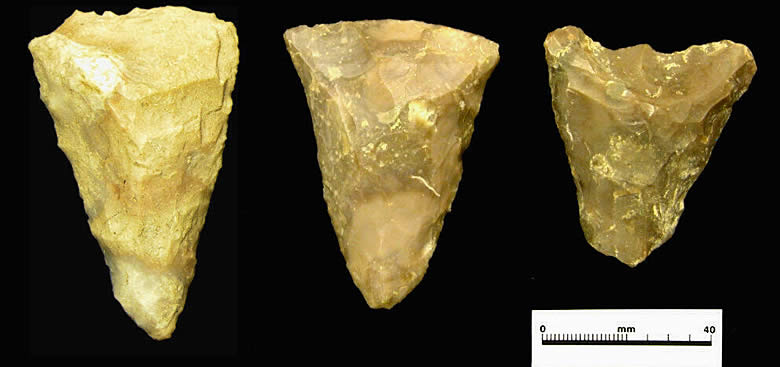

A distinctive polyhedral

core, from which a Clovis knapper removed a series of

long, parallel-sided flakes (blades), was found in Zone

4. The blades could either be used as tools for cutting

and slicing or could be knapped further and shaped into

bifaces, projectiles, and other tools. Photo by Aaron

Norment.

|

|

Angostura points. This style

of lanceolate dart tip was made during very Early

Archaic times some 9000 years ago. Some often

have fine, parallel flaking. Photo by Aaron Norment.

Click to enlarge and see more examples.

|

A simple flake is an effective

cutting tool. This specimen was recovered from

Zone 4 Late Pleistocene deposits. Photo by Aaron

Norment.

|

|

Prehistoric toolmakers used many different

tools and a variety of resources in their work. From

stone, bone, leather, sinew, shell, and plant fibers,

these early craftsmen created weapons and tools, baskets

and mats, grinding implements, clothing and sandals,

ornaments, and works of art. Few perishable materials

survived the damp conditions at Kincaid. We know from

other sites in the more-arid western regions, however,

that items of wood, fiber and other organic materials

would have made up the bulk of prehistoric hunting and

camping gear.

Chipped stone tools constituted the great

majority of artifacts at the shelter, including projectile

points, scrapers, knives, perforators, adzes, and a

variety of toolmaking gear and chipping debris. Prehistoric

stone knappers would have used rounded hammerstones

as well as bone and antler batons to remove flakes from

larger pieces of chert (flint) or other stone suitable

for flaking. Sharp-edged flakes derived from this process

made efficient cutting tools in themselves, or could

be chipped further and finished using finer tools, such

as antler tines. For other tasks, chipped stone burins

or gravers may have been used both for cutting and grooving

bones and for ornamental incising.

Bone tools such as these may have

been used for weaving plant strips into matting and

for leather working. The thin polished bone shown at

top is a needle, likely used in sewing.

|

Perforators, some of which

were made on the bases of gouges (lower left)

or projectile points (lower right), were found

throughout the deposits, and would have been used

for drilling or punching holes in wood or leather.

|

A heavy chopper such as this

one may have been used for cutting or pulverizing

fibrous plants.

|

|

|

|

An Early Archaic Merrell

point.

|

Early Archaic Martindale

points are distinguished by an expanding "fishtail"-shaped

base.

|

This heavily worn

Bell point was one of only a few points associated with

the Middle Archaic period. In pristine condition, it

would have had long barbs extending to its base.

|

|

|

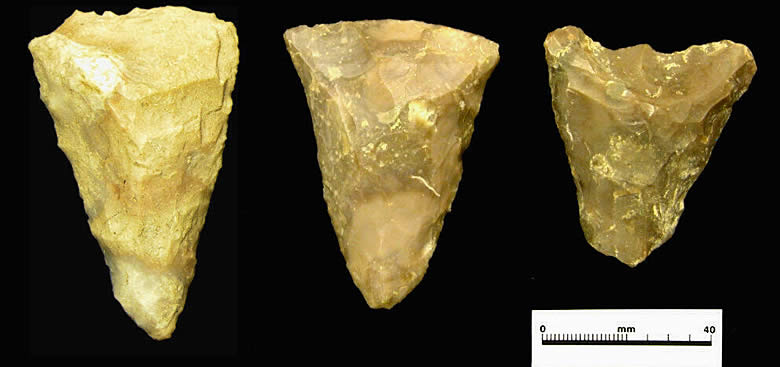

Pedernales knives? This series of Late

Archaic Pedernales points shows the changes in shape that

occurred with use, as their edges were worn down and then

resharpened. Archeologist Mike Collins believes the points

may have been recycled and used as knives after they were

no longer serviceable as projectile points. Photo by Aaron

Norment. Click to see closeup example of resharpening.

|

"Early Triangular"

dart points typical of the latter point of the

Early Archaic.

|

Several Late Archaic Montell

points indicate a type of use and reworking which

reduced them vertically, rather than laterally,

as in the case of the Pedernales "knives" shown

above. Projectile points often show impact or

snap fractures (including missing tips), caused

by striking an object (such as an animal), which

removed the tips. After such incidents, hunters

reworked points to create a new tip, but reduced

the overall size in the process. Click to see

more.

|

Arrowpoints, signaling the

shift to bow and arrow hunting technology about

1000 years ago, were found chiefly in the uppermost

layers. A variety of types are shown, including

Perdiz points (specimens A-L) that were part of

the tool kit likely used by buffalo hunters, roughly

700 years ago. Drawings by Hal Story.

|

|

Campbell identified almost 50 types of

projectile points from Kincaid, including dart points

and arrow tips. These diagnostics, or time markers,

span almost all known cultural intervals in the region.

A number of projectile points may have

served multiple purposes. For example, archeologist

Mike Collins believes that many Pedernales points—a

ubiquitous Late Archaic type found across much of central,

south, and west Texas—were recycled for use as

knives, judging from many specimens which have been

worn down and resharpened repeatedly along their lateral

edges. Several have been reduced to an almost lanceolate

form with no barbs or shoulders remaining, as shown

in the above photo.

In contrast, the series of later Montell

points shown at left (in the enlarged image) suggests

more predominate use as projectile points. This type

of use typically causes vertical reduction in size.

For instance as points were fractured on the tip or

snapped on impact, they were reworked to create a new

tip of a shorter point.

One unusual Paleoindian projectile point base recovered

from Zone 4 is made of obsidian, a type of black volcanic

glass that rarely occurs naturally in Texas. It is lanceolate

in form with a contracting base; both sides have been

flaked in parallel patterning. Although the morphology

of this point is enigmatic, its Late Pleistocene context

suggests an early type, such as Clovis. Trace element

analysis on a small fragment of the base indicated the

material derived from a geologic source in Queretaro,

Mexico, roughly 620 miles (1000 km) to the southwest.

According to archeologist Thomas R. Hester, who coordinated

the obsidian study, Paleoindian projectile points made

of obsidian are rare in Texas.

Campbell lists almost 100 cores of several

different types in the Kincaid inventory, including

several blade cores. One small, nearly expended, polyhedral

blade core was found in Zone 4 and is attributed to

Clovis peoples. The remaining blade cores from Zones

5 and 6 probably were made by Late Prehistoric Toyah

folk, who also used blade technology to make their tools

and weapons.

|

Middle and Late Archaic points

identified by T. N. Campbell and drawn by Hal

Story. Top row, Nolan. Bottom row (l-r), Nolan,

Langtry, Almagre. The alternately beveled stem

is a characteristic technical attribute of the

Middle Archaic Nolan type. Almagre likely is an

unfinished preform, or early stage, of a point

such as Langtry.

|

Flakes with trimmed edges,

serrations, and graver points likely made good

tools for hideworking, plant processing, and other

tasks.

|

Scrapers and gravers for a

multitude of purposes. The sharp points on the

tools (gravers) in the bottom three rows could

engrave shell or bone ornaments and stone pebbles.

Drawing by Hal Story.

|

|

|

Late Archaic points or knives, known as

Kinney type, illustrate the progression of wear and attrition,

as the edges are worn down and they are resharpened repeatedly.

Because of the flute-like, vertical flake removals from the

base, Kinneys have been mistaken for Paleoindian points. Drawings

by Hal Story.

Woodworking and Other Tasks

|

Examples of unifacial Clear Fork tools.

The specimens at left and center, from midden deposits (Zone

6), were probably used in an adze-like fashion to shape bone

or antler tools, based on a distinctive polish detected during

microscopic examination of the bits (the wider, beveled ends).

The stone tools would have been mounted in a wood or bone

haft to facilitate use. Photo by Aaron Norment.

|

Bifacial Clear Fork tools are

flaked on both sides, but have a beveled working

edge on one face. It is not known whether there

were different uses for bifacial and unifacial

forms of the tools, but there does seem to be

a difference in their ages. Although the specimens

shown were recovered from undatable backdirt piles,

bifacial Clear Forks from other sites were found

in early contexts and associated with Paleoindian

and Early Archaic points ( for example, the Wilson-Leonard

and Baker Cave sites). Photo by Aaron Norment.

|

A unifacial Clear Fork Tool

that has been rejuvenated after the bit (upper)

end was removed. As the tools were used, the bits

became more steeply beveled and less effective.

Knocking the bit off provided a fresh edge with

a very sharp, acute angle. Several broken ends

and bases were found at Kincaid. Sketches by Pam

Headrick.

|

|

Several types of bevel-edged tools, or

adzes, used in woodworking, boneworking, and perhaps

hide scraping, were recovered from Kincaid. One type,

known as Clear Fork tools or gouges (because of their

initial classification at sites near the Clear Fork

of the Brazos River in northwest Texas), encompasses

both bifacial (chipped on both sides) and unifacial

(chipped on only one side) forms used by prehistoric

peoples from Paleoindian to Late Archaic times. Another

type, termed Guadalupe tools because of their predominate

distribution in the Guadalupe River basin of south Texas,

are long, thick, and rounded with a sharply truncated

bit (or working) end. At other sites, these tools have

been found chiefly in Early Archaic contexts. More than

25 Guadalupe tools were found at Kincaid.

Prehistoric workers put these tools to

heavy use, as is evidenced by battering and wear on

the bits and by the reworking and gradual attrition

of the tools. Tool bits broke off during use or were

deliberately knocked off and re-sharpened by the workers

to create a fresh, more acute-edged, and more effective

working end, as is illustrated in the example above.

The specimen at right has been reduced by use and/or

successive resharpenings to a size roughly half that

of most of the other specimens.

UT-Austin archeologist Dale Hudler examined

40 of the 45 Clear Fork tools from Kincaid in 1996 as

part of a larger study to try to determine usage of

195 tools of this form. Microscopic analysis of the

bits, or beveled-edged ends, of the tools showed polish

and striations which was then compared to that on replica

tools used in a variety of experimental uses. Six Kincaid

specimens (one bifacial and five unifacial) had a distinctive

"smooth, linear polish" on the bit which Hudler

correlated with use on a very hard contact material,

such as bone or antler.

Hudler also determined that the unifacial

Clear Fork tools from Kincaid tended to be wider than

most others in the statewide study. However, variations

in shape, size, and bit end morphology of both unifacial

and bifacial Clear Fork tools have not yet proven to

be meaningful. More likely, these differences in morphology,

particularly in length dimension, simply reflect use

and resharpening.

|

These long, narrow, bevel-edged

Guadalupe tools were likely used for woodworking.

They are found almost exclusively in South Texas

sites, particularly within the Guadalupe River

basin . Photo by Aaron Norment. Click to see more

examples.

|

Drawing of a Guadalupe tool

from Kincaid, showing shape and angle of the bit

(upper) end and overall flaking. Illustration

by Pam Headrick.

|

|

|

Grinding and Milling Implements

Pecked and ground stone milling tools

were not common at Kincaid. The inventory consists of

three complete grinding slabs, or metates, four

fragments, and some 45 handstones, or manos.

With few exceptions, all were found in Zone 5 or are

unprovenienced.

The metates are worn; one shows use in

a back and forth motion, another in a circular motion.

A third has a circular basin that is roughly pitted.

The manos showed a variety of wear, including

grinding facets and striations, while others had central

pits, or slight depressions. These pitted specimens

may have been used as anvils, or platforms, for cracking

nuts. Many manos showed combinations of wear patterns.

Perhaps prehistoric cooks used these tools

for multiple purposes: a handstone for grinding seeds

and other foods, a platform for cracking nuts, and as

a surface for cutting fibrous materials, meat, or hide.

(Other examples of possible cutting platforms are shown

in Mysterious Stones section.)

|

Striations, stains and polish

cover this odd limestone tool that may have been

used for a variety of purposes, including grinding.

The striations, or cut marks, in the central pit,

suggest that a soft material may have been cut

on top of the stone. There are also pecks in the

depression, perhaps from pounding nuts. ( See

detail.) Click to enlarge. Photo by Aaron

Norment. |

Examples of grinding implements

from Kincaid. The shallow limestone metate, or

grinding slab fragment, at top has been worn down

from heavy use. The fragment is roughly 12 inches

(30 cm) in length. Manos, or handheld stones,

such as those at bottom, would have been used

to grind seeds, nuts,and plant bulbs into a flour-like

meal.

|

|

Prehistoric peoples must have

hauled this heavy cobble many miles to bring it

to the shelter. More than 12 inches (30 cm) in

length, the stone is basalt, or poryphry, a fine-grained

volcanic material that does not occur locally

but is found naturally in the Central Mineral

region (Llano Uplift) to the northeast. Highly

polished, the stone is also scratched and pitted

on one face, as if it had been used in grinding.

There are also small patches of red ocher stain,

indicating it may have been used to pulverize

pigment. Quite likely, this unusual artifact was

used in many different ways. Click to enlarge.

|

|

Ornaments and Special Objects

|

Ornaments made of freshwater

mussel shell may have been suspended on cording

and worn as jewelry. The object on left was from

Archaic levels in a terrace test pit, the one

on right from disturbed fill. Photo by Aaron Norment.

|

A polished, hollow bird bone has been grooved

and snapped on one end, perhaps to make a bead.

Bone beads strung on fiber cords have been found

in other sites, particularly in the dry shelters

of the Lower Pecos region.

|

This drawing of a grooved and snapped bird bone bead shows faint sets of lines decorating the object. Drawing by Hal Story. |

|

A number of objects from Kincaid were

less utilitarian and practical than stone tools and

weapons. Along with a quantity of engraved stones and

paint-making materials (see Mysterious Stones

section), there were several artifacts of shell and

bone likely worn for personal adornment as well as fragments

of a probable steatite pipe.

Two pendants made of very thin, freshwater

mussel shell had conical perforations drilled from the

concave surface of the shell. The objects may have been

worn suspended around the neck as jewelry. There were

also several pieces of bone that appear to have been

beads. These hollow sections had been grooved and snapped,

and were likely strung on a cord as a necklace.

Generally, the collection of bone and

shell artifacts was scant, however, and this is doubtlessly

due to damp conditions in the shelter which took their

toll on these and other, even more perishable items

made of fiber and wood.

Eight fragments of a vessel made of soapstone

(steatite), shown at right, appear to be the remains

of a tubular pipe that, based on rim sections, was roughly

2.5 inches (6.4 cm) in diameter. Soapstone is a metamorphic

rock, a talc which occurs in both eastern and western

parts of the United States. When freshly mined, it is

soft and can be easily shaped with hand-held tools.

Tool marks can be seen on both the interior and exterior

of the Kincaid vessel. In Texas, natural deposits closest

to the site are in Hudspeth county to the west, or in

the Llano Uplift, some 65 to 100 miles northeast of

the Kincaid site.

|

This limestone pebble may have

been worn as a pendant, with cording passed through

the hole cleanly drilled near one end. Photo by

Aaron Norment.

|

Curved fragments of a soapstone

(steatite) vessel perhaps once formed a long,

tubular pipe for smoking. The fragments were found

near the top of Zone 5 Archaic deposits. Photo

by Aaron Norment.

|

|

|

Pottery

This large rim

sherd had deeply scored lines across the exterior,

a technique perhaps used to make the vessel less

slippery if it was used to carry water. Photo

by Aaron Norment.

|

One of two

sandy textured sherds found at Kincaid. Photo

by Aaron Norment. Click to see full image.

|

|

Fragments of

thin-walled, bone-tempered pottery typically are

termed "Leon Plain."

|

During the late part of the prehistoric

period (roughly A.D. 1300), Kincaid occupants began

using pottery vessels to store food, water, and other

resources. Investigators found some 50 pottery sherds,

chiefly in the upper levels of terrace deposits in front

of the shelter. At least three different pottery types

are present, representing perhaps eight or nine different

vessels. These include thin-walled, bone-tempered sherds

(typically referred to as Leon Plain) and a thicker

version with vertical lines scored across the exterior

(cf., Boothe Brushed). Other sherds had a sandy texture

and apparent grog temper (crushed pottery sherds mixed

into the clay paste). Prehistoric potters used various

tempering agents, or additives, including sand, grit,

crushed shell, and bone, to improve the clay texture

and cause more even drying and firing.

Pottery-making technology was late to

catch on over much of what is now central and south

Texas. The Caddo villagers of east Texas made exceptional

pottery as early as 1000 years ago. The pottery at Kincaid

was made during the latter part of the Late Prehistoric

(Toyah interval, circa 400 to 700 years ago) and some

of it (the Leon Plain sherds) can be attributed to mobile

groups who used Perdiz arrowpoints and a distinctive

tool set associated with buffalo-hunting. Similar sherds

were identified at the nearby La Jita site.

|

|

Buttons and Bullets: Historic-Period Artifacts

|

More-recent visitors to Kincaid

left behind a variety of trash including bullets

and shells, construction materials, and broken

bottles. Photo by Aaron Norment.

|

This brass button was identified

by Col. Marvin Crimmins of San Antonio as that

of a Confederate Infantry officer's jacket, as

signified by the letter "I."

|

|

A few historic-period artifacts were found

at Kincaid, indicating the presence of visitors—hunters,

fishermen, soldiers (or former soldiers), ranchers,

and picnickers—from the 1850s to modern times.

Along with a variety of ammunition, metal construction

materials, and glass, investigators found an 1857 half-dime

and a brass button from a Confederate infantry officer's

uniform. T.N. Campbell, in communicating with a militray

expert in San Antonio, learned that the button likely

is attributable to an officer on the staff of General

H.H. Sibley, who led a brigade through the area of Sabinal

in 1861 en route to New Mexico.

Ammunition found at the site included

cartridge cases bearing head stamps marked W.R.A. Co.

(Winchester Repeating Arms Co.) and variants, assignable

to the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

July 22, 1954

Dear Col. Crimmins,

I wonder if I might draw on your great store of military

knowledge for help in identifying a brass button found

in the top six inches of an archaeological site near

Sabinal. It appears to be from a military uniform. It

is 19.5 mm in diameter… . The top is convex and

has a loop for an attachment and is stamped "P.

Tait & Co., Limerick." Incidentally, at the

same level came a U.S. Half Dime, 1857…

Any light you may be able to throw on this button will

be much appreciated.

Sincerely yours,

T.N. Campbell, Chairman

|

An 1857 U.S. half-dime (both faces shown) was found by investigators in the upper layers of terrace deposits in front of the shelter. Photo by Aaron Norment. |

Letter from Col. Crimmins identifying

the brass uniform button found at Kincaid. Crimmins

noted that Confederate troops posted to Camp Sabinal

(near Kincaid Shelter) were not uniformed, therefore

the button may have dropped from the jacket of

troops in Gen. H.H. Sibley's brigade who passed

through Sabinal en route to New Mexico. The brigade

fought in a battle near Fort Craig in 1862. Click

to enlarge and read

full letter. |

|

|

| |