View west across central area of

Paleoindian dig at its conclusion.

|

Pointing out the Paleoindian stratigraphy.

The upper hand points to the "Folsom" zone,

the layer within which the main Paleoindian component

occurred at Pavo Real. The bottom hand points to a piece

of broken chert in a lower gravel lens. At least one

definitively man-made chert flake was found well beneath

the Clovis-age deposits.

|

Late afternoon view looking southwest

across the Paleoindian excavations at Pavo Real with

Leon Creek on the right. This photograph was taken at

the end of the project.

|

Paleoindian artifacts exposed in

a two-meter excavation unit at Pavo Real. After exposure,

the archeologists carefully plotted each item on a map.

|

Archeologists Bob Stiba (left) and

Glenn Goode take notes and plot artifact locations during

the Paleoindian excavations.

|

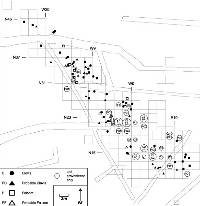

Distribution of artifacts that could

be assigned to Clovis and Folsom components. As this

map shows, the two assemblages occurred over essentially

the same areas. They were not separated vertically,

either.

|

Clovis points from Pavo Real.

|

Clovis end scrapers made on blades.

|

Miniature points (left) and two fragmentary

Folsom points (right).

|

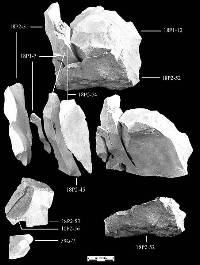

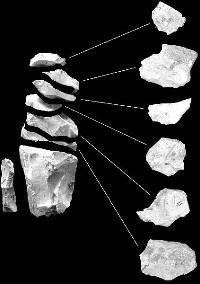

Refit Group 1 consisted of a core

and eight flakes that conjoined the core and one another.

This composite photo shows how the pieces fit together.

(The numbers are specimen numbers.)

|

Map showing the distribution of the

items found in Refit Group 2.

|

| |

Natural chert cobbles from

the limestone "bench" at Pavo Real that have been split with a

geological hammer. The natural dark gray color of the PRVEC (Pavo Real Variety

Edwards Chert) can be seen in the center of the broken pieces. The outer

rinds are heavily patinated, or weathered. All of the site's Paleindian

artifacts were thoroughly patinated and appeared white. |

The Paleoindian excavations at Pavo

Real drew numerous visiting experts. Here TxDOT archeologist

Frank Weir points out a stratigraphic circumstance to

geologist Glen Evans (felt hat) and archeologist Dee

Ann Story (with camera). Jerry Henderson (solid red

shirt) and Chuck Johnson (dark brown shirt) look on.

|

Refit Group 5 consisted of a blade

core, six core tablets and a blade. Here they are shown

fitted together. Core tablets are specialized flakes

that remove the top (platform) of a blade core in order

to create a new platform.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

In early Paleoindian times (about 12,000-13,600

years ago) small groups of Clovis and Folsom

people camped at Pavo Real for short stays during which they

refurbished some of their tools and weapons from the abundant

supply of chert they found at the site. Clovis and Folsom

are the names of archeological cultures or cultural traditions

named by archeologists for their distinctive lanceolate spear

and dart tips (projectile points). The finding of a few artifacts

below the main Paleoindian layer at Pavo Real suggests that

the locality was visited by people at an even earlier time.

These may have been early Clovis people, although we are not

sure.

Although archeologists think that Folsom culture

succeeded Clovis culture, artifacts from the two cultures

were found in the same layer at Pavo Real and could not be

"stratigraphically separated." In other words, the

Folsom materials did not occur in a separate layer overlying

that containing the Clovis materials. Perhaps the Clovis and

Folsom occupations of the site (and these may well represent

more than two visits to the site) were not separated by very

much time. Alternatively, sediment accumulation may have been

so slow that Folsom peoples camped on the same surface as

had Clovis peoples in earlier times, such that the artifacts

from both were intermingled.

Throughout the Paleoindian occupations, knappers

made use of chert obtained at or very close to the site. Lithic

(stone) artifacts are essentially the only preserved cultural

evidence upon which we can base our interpretations of the

lives and activities of those who camped at Pavo Real. Techniques

of stone tool manufacture and aspects of stone tool use can

be inferred in some detail; from these inferences, the setting

of the site, and comparative data from other early Paleoindian

sites, limited interpretations can be made regarding broader

aspects of the prehistoric lifeways represented at this site.

Pavo Real was subject to repeated flooding

during the era in which the Paleoindian occupations occurred.

It is situated on the inside of a bend in Leon Creek on a

point bar in a region known for flash flooding. What is preserved

of the site is a flat terrace surface bounded on its east

by a low bedrock bench and on its west by a steep bank dropping

off toward the creek. At the time of the Clovis and Folsom

occupations, the site area was minimally 50 meters long and

40 meters wide (about 160 by 130 feet). Materials left by

these early occupants were buried by overbank flood deposits

across the flat terrace. It is likely that some evidence of

the early Paleoindian occupations was washed away at times

when high-energy floods eroded the creek bank.

In 1979-1980 when Pavo Real was dug, there was

little challenge to the Clovis First theory that Clovis

was the first North American culture or to the widely held

ideas that Clovis was succeeded over much of its range by

Folsom, and that the archeological remains left by both of

these were characteristic of nomadic big-game hunters. Clovis

hunters were thought to have preyed on mammoths and Folsom

hunters on now-extinct species of bison. It was often hypothesized

that early Paleoindian hunters may have been responsible for

the extinction of these members of the terminal Pleistocene

megafauna (large Ice-Age animals).

Excavations at Pavo Real began in the belief

that only Archaic archeological deposits were present, a view

that was reinforced when a seemingly artifact-free gravel

layer was encountered in test units below artifacts and features

of early Archaic age. Such gravels were (erroneously) considered

by the site's investigators to be the geologic marker of

the glacial maximum (peak of last Ice Age) at 17,000 or

18,000 years ago. Near the close of scheduled excavations,

a Clovis point was found at the base of the Archaic deposits.

A hurried testing ensued in search of additional Paleoindian

artifacts and these were, in fact, found. Most of these were

found within a flood deposit that was below the gravel then

thought to represent the glacial maximum.

The dig was extended, excavation strategy was

modified, and several experienced archeologists were added

to the field crew, but no specific research goals were identified

and pursued. Machines were used to remove the remaining Archaic

deposits above the layer (called the Folsom zone or Zone

5) bearing the Paleoindian artifacts. Zone 5 was excavated

by hand, and a high proportion of the exposed artifacts was

mapped in place. A number of these artifacts included diagnostics

(distinctive artifact types) matching Clovis and Folsom assemblages

at other, sealed sites.

In much the same way that Clovis and Folsom

Paleoindian artifacts were accidentally discovered beneath

the Archaic deposits, another component of unknown affiliation

was found by chance in deposits underlying the unit containing

Clovis and Folsom materials. This lowest cultural component

was barely investigated and too little was recovered to suggest

what affinities it might have to other early assemblages.

For the most part, it seems to date from early Clovis times.

(A single, apparently man-made flake was recovered from a

still deeper deposit that clearly predates Clovis, but it

is hard to say much about a single flake.)

Analysis Results

Two of the preliminary questions addressed by

Michael Collins and his research team at the Texas Archeological

Research Laboratory were: (1) Were the Clovis and Folsom materials

in primary context (where they were originally dropped)

or secondary context (moved and redeposited during

floods)? and (2) Was there evidence of any stratigraphic separation

between the Clovis and Folsom components?

There is no geologic evidence that the cultural

materials were transported from elsewhere and deposited together

(such as by stream or flood action), nor was there any indication

of a stratigraphic break or separation between Clovis and

Folsom materials. These geological inferences are entirely

consistent with the archeological evidence. The physical condition

of the artifacts do not indicate that they were transported

nor is there horizontal size-sorting suggestive of stream

transport; further, the Clovis and the Folsom artifacts exhibit

the same degree of patination (weathering) and surface damage.

The most compelling evidence for primary context is the large

number of refits, that is, artifact fragments that

fit together (conjoin), showing they were once part

of the same tool or were made from the same piece of chert.

The presence of pieces of large and small knapping debris

that conjoin one another and were found close together in

Zone 5 is a clear signature of artifacts in primary context.

Within Zone 5 there is no evidence of the vertical

separation of Clovis and Folsom artifacts. Geologically, Zone

5 accumulated intermittently over an unknown interval of time

beginning before and continuing after the majority of the

Clovis and Folsom artifacts were dropped. Probably the best

explanation for the component mixing at Pavo Real is that

natural deposition was slow enough for all of these cultural

materials to accumulate in a very few centimeters of sediment

but rapid enough that no stable surface formed.

Various techniques were used to date the Paleoindian

deposits and related geological layers at Pavo Real. Tiny

fragments of charcoal were found in the site's deeper and

earlier deposits, giving the original investigators hope that

these could be used to obtain radiocarbon age estimates of

the Paleoindian occupations. Unfortunately, the resulting

dates fell with early Archaic times, suggesting that the charcoal

was introduced into the lower deposits by pit-digging or other

disturbances. Years later, attempts to date snail shells (one

of the few organic materials that did survive) also were not

satisfactory for complicated reasons we won't go into. Finally,

a technique called OSL

(optically stimulated luminescence) dating was attempted.

OSL dating was more successful in that estimates for the absolute

ages of Zones 5, 7, and 9 were obtained. Unfortunately, this

dating technique does not yield precise age estimates and

results n rather wide ranges of possible ages.

It appears likely that the Paleoindian component

at Pavo Real was nearly totally excavated. Artifact counts

dropped off abruptly along the west, south, and east margins

of the excavated area. On the north, chert counts were still

high, but the proportion of these that were cultural in origin

was dropping off and the percentage of natural or stream-rolled

chert fragments was increasing. The exposed area of occupation

was roughly 50 m by 12 m. A majority of the artifacts were

found in a layer that was no thicker than 20 centimeters (8

inches).

To sum up the key findings regarding the Paleoindian

component at Pavo Real: (1) Clovis and Folsom artifacts were

found together in a loamy fluvial (water-laid) deposit with

no evidence for post-depositional (later) mixing or that they

accumulated on a stable land surface; (2) the Clovis and Folsom

artifacts were dispersed over an elongate area covering about

550 square meters (almost 6,000 square feet); (3) very little

of the Paleoindian component went unexcavated; (4) the Paleoindian

artifacts were buried by repeated overbank flooding of relatively

low energy; and (5) there is no indication that the stream

moved these artifacts prior to their burial.

Because of these factors, the Paleoindian artifacts

and two cultural features (both clusters of artifacts) can

only be attributed to the Clovis or to the Folsom component

on the basis of diagnostic features—lacking these, no

specific cultural assignment is possible. Collins made the

following assignments: there is 1 Clovis feature, 1 unassigned

feature, 145 Clovis artifacts, 57 Folsom artifacts, 99 unassigned

artifacts, and 22,933 pieces of unassigned debitage (roughly

16,000 debitage pieces are definitely cultural—the others

are probably natural fragments). There are also numerous large

stones scattered throughout the component that are too large

to have been moved by floodwaters without having also moved

lots of artifacts. Therefore, the majority of the large stones

are considered manuports, meaning they were carried

there by humans and perhaps used as anvil stones or weights

to hold down the edges of hide coverings.

Field investigators believed that the two Paleoindian

cultural features—concentrations of chipped stone—represented

distinct knapping events (occasions when one or more prehistoric

flint-workers sat down at the spot to produce or rework tools).

The first, Feature P3, consists of small, non-diagnostic flakes

from more than one piece of raw material. In the absence of

refits, there is no basis for attributing this cluster of

flakes to a single knapping event. The other, Feature P4,

consists of a core and various debitage pieces shown by refitting

to connect with a Clovis blade core and other debitage found

outside of the feature.

Pavo Real As A Lithic Workshop

Most of the behavioral evidence preserved and

recovered from the early occupational levels at Pavo Real

relates to the knapping of stone. This evidence is dominated

by tool-making debris produced by breaking up pieces of the

local variety of Edwards chert. While it seems likely that

the quality of the local chert was somewhat better (less weathered)

13,000 years ago than it is now, it was still plagued with

many flaws and a variety of textures. Consequences of the

flaws are evident throughout the knapping debris. In the general

region, better grades of Edwards chert were readily available

at the time to the people who camped at Pavo Real. Was Pavo

Real occupied because, or in spite of, the abundant but less-than-ideal

chert cropping out at the site?

The bulk of the Paleoindian assemblage from

Pavo Real is made up of non-diagnostic lithic debitage (generic

flakes, chips, and chunks of chert). Much of the evidence

stems from earlier stages of reduction in this material and

attests to similarities in the knapping process before the

distinctive pieces that characterize Folsom or Clovis take

form. There are also numerous simple tools such as unifaces

(shaped on only one face) and some bifaces (shaped on both

faces) that cannot be assigned to either Clovis or Folsom.

One curious set of Paleoindian artifacts consists

of four miniature lanceolate points that cannot be assigned

to Folsom or Clovis. Similar small-scale projectile points

have been found at other sites in Paleoindian contexts of

Clovis, Folsom, and Hell Gap cultures. The four miniature

pieces in this collection may include points made by knappers

of Clovis or Folsom affiliation, or both.

Clovis Lithic Technology

The majority (72%) of the 202 Paleoindian lithic

artifacts at Pavo Real that can be assigned to Clovis or Folsom

on the basis of morphology (shape) are of Clovis affiliation.

These include fluted projectile points, bifaces, bifacial

debitage, blade cores, blades, tools on blades, and blade

production debitage. The accompanying photographs provide

examples of most of these. The vast majority of the Clovis

artifacts are made on the local material.

All of the artifacts inferred to represent Clovis

biface technology (as opposed to blade technology)

relate to the production, use, maintenance, and discard of

fluted projectile points. There are two projectile points

that appear to have been discarded at the end of their usefulness.

Such pieces are typically found near sources of raw material

in association with evidence for point manufacture, exactly

the circumstances seen at Pavo Real.

Nine fragmentary Clovis bifaces found at Pavo

Real are consistent with the idea that the site was a workshop

where weapons were retipped. These fragments appear to be

Clovis point preforms (unfinished points) and a fragmentary

channel flake (specialized flake that creates the flute).

The bifaces are typical of unsuccessful attempts to produce

Clovis points.

There is substantial evidence for blade production

at Pavo Real. Both of the blade core forms, conical and wedge-shaped,

previously recognized in Clovis assemblages are present as

well as various kinds of blades, blade fragments, and blade-core

preparation flakes. The Clovis assemblage from Pavo Real also

includes blade tools such as end scrapers (blades with

one end that has been shaped into a circular tool edge). Most

of the end scrapers have a single notch on one edge, presumably

to facilitate hafting; they also have evidence of having been

resharpened.

Dale Hudler examined each of the blades tools

from Pavo Real under a microscope and found evidence of use

wear (such as edge damage and polish) on many of them. The

wear patterns he observed are considered characteristic of

contact with both plant and animal materials, with the latter

the more common. Such evidence shows that more went on at

the site than just tool making. The Clovis people who camped

here probably hunted nearby, butchered animals, gathered plant

foods, made tools or clothes out of leather and wood, and

so on.

Folsom Lithic Technology

Characteristic Folsom lithic artifacts present

at Pavo Real include fragmentary Folsom points, aborted Folsom

point preforms, channel flakes, thin retouched flakes, ultrathin

biface fragments, spurred end scrapers on flakes, large thin

unifaces, and multiple gravers. It is possible that some of

these could actually be of Clovis origins.

The Folsom artifacts at Pavo Real are exclusively,

or very nearly exclusively, made of the local chert. Most

of these pieces indicate that the Folsom knappers had problems

similar to those encountered by Clovis knappers. There are

multiple examples of knapping failures caused by flaws in

the raw material. Evidence for early stages in the Folsom

reduction technology were not identified in this assemblage.

This is almost certainly because they are not distinctive

enough to be recognized as such.

Two fragments of Folsom points were presumably

removed from their hafts and discarded at the site. Also present

is evidence of Folsom point manufacture. This is similar to

the Clovis assemblage at the site and is also inferred to

be the result of retooling (removing broken or worn out tools

from the wooden foreshafts of weapons and replacing these

with new ones). Folsom preforms exhibit a number of

failures, some resulting from knapping error and some from

insurmountable flaws in the raw material. The Folsom channel

flakes recovered from Pavo Real seem to have been successfully

detached, suggesting that completed Folsom points were probably

produced at the site from the local chert.

Bifaces other than preforms include two fragmentary

ultrathin bifaces and two thin flakes with bifacial pressure

flaking. Ultrathin bifaces, as the name suggests, are

large and extraordinarily thin bifaces thought to be cutting

tools (knives). Use-wear evidence confirming this function

was not found on the Pavo Real tools, perhaps because the

evidence for that use was removed by resharpening.

Numerous end scrapers on flakes from Pavo Real

exhibit the classic attributes of Folsom end scrapers. Thin

retouched flakes and flakes with multiple graver tips are

also considered to be of Folsom affiliation. The retouched

flakes may be cutting tools while the items called gravers

are too delicate to be used in the engraving of any durable

material such as wood or bone unless extremely lightweight

incisions were produced.

Pavo Real as a Paleoindian Site

At a general level of comparison, the Clovis

assemblage compares favorably with Clovis camp sites (as

opposed to kill sites and other specialized site types). In

Texas, at least five Clovis camp sites are indicated in the

ecotone along the Balcones Escarpment (Gault, Wilson-Leonard,

Vara Daniel, Spring Lake, and Kincaid—see map in "Site

and Its Investigations"). The emerging pattern seems

to be that of generalized hunter gatherers who would find

an ecotonal setting such as Pavo Real ideal for the variety

of resources that could be accessed with relatively little

travel. This idea contradicts the prevailing model of Clovis

peoples as highly mobile big game hunters.

Pavo Real is consistent with considerable data

that now exists on Clovis and on Folsom site distributional

patterns. Clovis site distributions and Clovis subsistence

data across North America reflect generalized hunting and

gathering lifeways, not big-game hunting specialization. To

some of us engaged in the search for the origins of human

occupancy of North America, it seems highly improbable that

this pattern represents the adaptation of the founding populations

of the continent (as expected according to the Clovis-First

theory). Clovis culture is simply too well adapted to diverse

resources in too many kinds of environments to be recent arrivals

to those environments.

In its consistency with Clovis site distributional

data, Pavo Real reinforces this emerging pattern. The

keystone in the interpretive model of rapid Clovis expansion

into an empty continent is that specialized big-game hunting

is transferable to any habitat where big game are present,

but when the evidence is preserved, most Clovis subsistence

is based on small animals and probably also included plants.

Clovis knappers were intimately familiar with tool stone sources

all over the continent, including some that were relatively

obscure. Their familiarity with the resources of the continent

looks more like the end product of many generations of exploration

and learning.

Folsom, on the other hand, seems to

be the archeological manifestation of a specialized big-game-hunting

way of life. This in itself poses a challenge to archeology

since ethnographic analogs are lacking (no comparable human

societies survive). Pavo Real as a Folsom site seems consistent

with the distributional pattern of other Folsom sites and,

in that sense, adds to what is known about Folsom subsistence

strategies. As scholars struggle to better understand a truly

nomadic big-game-hunting adaptation, this distributional pattern

will be pivotal.

Were the Clovis and Folsom components better

separated at Pavo Real, undoubtedly more could be said about

the structure of their camps and the nature of the activities

that transpired there. As it is, Pavo Real provides additional

evidence of the regional-scale land-use behaviors of Clovis

and of Folsom peoples. Pavo Real is probably also a strong

indication that Clovis and Folsom folk camped at numerous

localities in the Balcones Escarpment ecotone. Given the long

history and current pace of urban and suburban growth in this

part of Texas, to say nothing of 13,000 years of erosion,

many of these campsites undoubtedly have been lost and such

losses will continue.

There are deep alluvial deposits in the valleys

of larger streams where they emerge from the dissected edge

of the Edwards Plateau and change to a lower gradient along

the margin of the Gulf Coastal Plain. These are precisely

the settings where early sites have a better chance of survival

because they are deeply buried. Sites formed in such settings,

where rapid rates of deposition would favor better component

isolation, would also have better conditions for preservation

of such materials as bone.

Concerted geoarcheological reconnaissance along

the alluviated valleys of such rivers as the Brazos, Little,

San Gabriel, Colorado, San Marcos, Guadalupe, Medina, Sabinal,

Frio, and Nueces as well as lesser streams along the Balcones

Escarpment ecotone should identify areas where latest Pleistocene

to earliest Holocene age deposits exist. Additional Clovis

and Folsom sites will likely be found well-preserved and stratigraphically

well-isolated in these settings. Such sites have the potential

to expand and refine our understanding of Clovis and Folsom

adaptations as expressed in the Balcones Escarpment ecotone

and glimpsed at Pavo Real.

|

Clovis point as it was found at Pavo

Real.

Click images to enlarge

|

FAQ: What are

assemblages and components?

Assemblages are groups of artifacts

made and left behind.... read

more>> |

View north-northwest along long axis

of Paleoindian deposits. The limestone bench that bounds

the east side of the occupation area stands out clearly.

|

Archeologist uncovers the concentration

of Paleoindian artifacts at Pavo Real designated as

Folsom Feature 4 (Iater renamed Feature P4).

|

Gradall at work removing the Archaic

deposits overlying the Paleoindian component, Fall 1979.

|

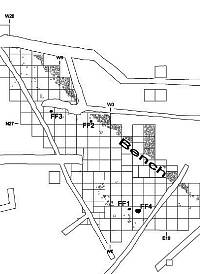

Distribution of Paleoindian features

as recorded during the field investigations. FF stands

for Folsom Feature. FF1 and FF2 were rejected as valid

cultural features during the analysis. The remaining

two features are clusters of knapping debris. Also shown

is the location of the limestone bench and numerous

manuports, large rocks obviously moved to these locations

by humans.

|

Large, partially reassembled chert

mass that Clovis knappers had broken apart at Pavo Real

early in the process of creating a blade core.

|

Selection of end scrapers made on

flakes and on blades. Those on blades are probably of

Clovis origin whereas those on flakes could be of either

Clovis or Folsom affiliation.

|

Selection of Clovis blades, including

some used as tools with little or no modification.

|

| |

|

FAQ: What is

lithic reduction?

Lithic reduction (or just reduction)

is the process of taking a relatively large, shapeless

piece of chert and... read

more>>

|

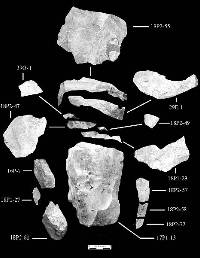

Refit Group 2 consisted of a blade

core, four core tablets, two platform preparation flakes,

and six blade fragments that have been refitted as shown.

|

Refit Group 4 consisted of an irregular

core and several flakes that conjoined the core and

one another. This composite photo shows the reassembled

piece and how the pieces fit together. (The numbers

are specimen numbers.)

|

Refit Group 5 disassembled. Compare

with photo, below left.

|

| |

| |

Jerry Henderson looks on

as a Gradall is used to remove Archaic deposits overlying the Paleoindian

component. |

|