|

FAQ: How and

why are archeological sites "recorded?"

Recording an archeological site involves

filling out a site survey form.... read

more>>

|

Initial excavations underway on

the north side of highway. Note the pool of water

in Leon Creek.

|

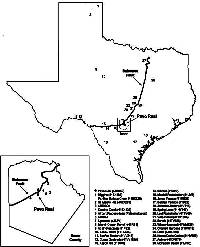

Map showing location of Pavo Real

and select other important Paleoindian and Archaic

archeological sites in Texas.

|

Archeological crew during excavation

of the Paleoindian component at Pavo Real. Top row,

left to right: Bob Stiba, Darrell Creel, Glenn Goode,

and Marshall Eiser. Bottom Row, left to right: Barbara

Baskin and dogs, Margaret Hausauer, and Jerry Henderson.

|

View south from Pavo Real across

the rolling terrain below the Balcones Escarpment.

To the south across the Gulf Coastal Plain, the natural

vegetation is dominated by thorny brush adapted to

hot, dry conditions.

|

| |

|

FAQ: What exactly

is a hearth?

The generally circular "beds"

or arrangements of cooking rocks that once formed....

read more>>

|

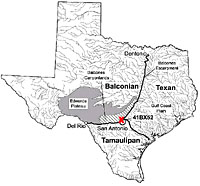

Site location relative to major

physiographic and biotic provinces of Texas. Click

for larger view.

|

View early in the investigations

of the western edge of the area that would become

the main focus of excavation. Note dry bed of Leon

Creek in background.

|

| |

Excavations in progress, fall 1979,

view looking northwest.

|

Excavation wall profile at Pavo

Real. The layer of rocks at the top is the outer edge

of a burned rock midden (Feature 4). The Paleoindian

deposit is marked by the red X. Elsewhere in the site

the two gravel layers above and below the Paleoindian

layer were more distinct.

|

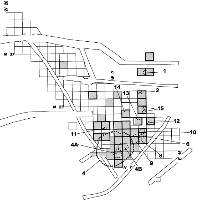

Plan map of main excavation areas

at Pavo Real. The trenches were dug by machines. Among

the hand-dug squares, those shaded gray show the Archaic

excavations. The Paleoindian excavations covered all

of the squares. The dashed and numbered areas show

the location of the Archaic features. Click to enlarge.

|

View of excavations near the end

of the field work as seen from cherry picker. Highway

construction is in progress in the background.

|

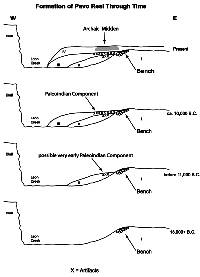

Schematic depictions of a cross-section

through the Leon Creek Valley at Pavo Real, showing

how the site formed through time. This reconstruction

is based on the geological evidence.

|

Twenty years after the soil monoliths

were boxed up and stored away, micromorphologist Heidi

Luchsinger of Texas A&M University carves out

small samples from which she will create thin sections

for microscopic examination. Micromorphology is the

study of sediments under a microscope to understand

how sediments and archeological deposits formed.

|

Consolidated sediment block removed

from the Zone 5 layer in one of the soil monoliths.

This 2-x-3 inch block shows that the Zone 5 sediment

became coarser and less compact toward the top of

the zone. The black tic marks at the top indicate

that the block is oriented correctly (i.e., top is

nearest the surface and toward the top of Zone 5).

Photo by Heidi Luchsinger.

|

|

Pavo Real was first recognized and recorded

in 1970 by two high school students, Bill Fawcett and Paul

McGuff, long after the original two-lane highway 1604 had

been built across Leon Creek. They had found the site after

TxDOT cleared a new, much wider right-of-way in anticipation

of expanding the road into an eight-lane thoroughfare. The

two students were searching the area for archeological sites

because they could see that subdivisions, roads, and shopping

centers would soon obliterate most traces of the many prehistoric

campsites present in northern Bexar County. They hoped the

information they recorded would be of use, as indeed would

prove to be the case. (Fawcett and McGuff both went on to

study archeology in college and become professional archeologists.)

The original site record was brief and noted

the presence of "fire pits" near the creek that

had created "a rise above the rest of the site."

On the surface it appeared similar to many other poorly

known sites in the area—just another seemingly unremarkable

place where prehistoric people had left behind evidence

of camping and tool making. A few years later, Dr. Thomas

R. Hester, then professor of anthropology at the new, nearby

campus of the University of Texas at San Antonio, visited

the site and recognized that the site might have deeply

buried deposits dating back to at least the early part of

the Archaic period. Hester alerted TxDOT archeologists to

the site's potential and urged the agency to investigate

the site prior to the construction of the highway.

In the late 1970s, federal and state laws

and regulations governing cultural resources were

in place, but the field of contract or cultural resource

management (CRM) archeology was still young and the "standard

operating procedures" were not yet standardized. Because

some of the funding for the highway expansion came from

the federal government, the impact of the construction on

potentially important "historic properties" (such

as archeological sites and old buildings) would have to

be considered under the National Historic Preservation

Act of 1966. Because site 41BX52 lay unalterably in

the path of the planned highway, TxDOT archeologists began

to evaluate the site's significance by carrying out test

excavations.

Before discussing the investigations further,

let's take a look at what archeologists call the "site

setting" of Pavo Real.

Site Setting

The general location of the Pavo Real site

figures prominently in the region's historical landscape

as well in as San Antonio's modern transportation network.

As part of it's unique natural setting, the site was located

on or near important but little known historic and, very

probably, prehistoric trails. The valley of Leon Creek,

which heads (begins) only 22 kilometers upstream from the

site, forms a natural corridor linking the Hill Country

of the southern Edwards Plateau, the Blackland Prairie to

the east and the Gulf Coastal Plain to the south. The site

is located within the Balcones Fault zone just below the

Balcones Escarpment, once known as the margin of Apachería

and Lomería Grande. The edge of the Edwards Plateau

is also known as the Balcones Canyonlands because of the

many deeply entrenched streams and rivers that drain the

plateau.

Historically, an old trail ran through the

natural pass formed by the Leon Creek Valley and linked

Bexar (modern San Antonio) and a Spanish Colonial presidio

popularly known as San Sabá (Presidio San Luis

de las Amarillas) in present-day Menard County. Early

settlers called this pass, la puerta (de las casas)

viejas (roughly translated as, "gateway

to the old houses" or "old pass"). The nearby

pass and the immediate vicinity of the Pavo Real site became

a documented Comanche trail leading northward from the springs

of San Pedro Creek in San Antonio. In the early history

of the settlement, the historical trail also may have been

called the camino de tehuacanas (an apparent reference

to the Tawakonis, a Wichita group commonly associated with

north-central Texas throughout the 18th century). By the

mid-19th century, this ancient trail became a major route

of German immigration from San Antonio into the Hill Country.

Today, the vicinity of the Pavo Real site

is the intersection of two major regional thoroughfares.

Interstate Highway 10 passes through the Leon Creek Valley

following the same basic route as the historical trail and

today, a few hundred years east of Pavo Real, carries an

average of about 181,000 vehicles per day. Loop 1604 West

runs along the Balcones Escarpment and today it carries

some 162,000 vehicles daily over Leon Creek and the former

location of the ancient campsite.

In addition to Pavo Real's location on a natural

corridor, three other factors help explain why prehistoric

peoples stopped to camp at Pavo Real: water, chert, and

ecotone. Leon Creek itself would have had water it

in year-round, even during droughts, at least in its deeper

holes. Until the early 20th century, Leon Springs (10 kilometers

upstream) and three other minor springs flowed freely (since

the early 1900s, groundwater pumping has severely reduced

or halted the flow of all springs in northern Bexar County).

Today very little water flows in Leon Creek except at times

of significant rainfall when it is subject to flash flooding.

The finding of water snails in the site's Paleoindian deposits

hint that there was a permanent pool of water at or near

the site early in its history. The relatively well-watered

valley would have provided habitat for many of the plants

and animals upon which prehistoric peoples depended.

The site area also has an abundance of chert,

the hard silica-rich rock often called "flint"

that prehistoric peoples used to fashion projectile points

and many tools. Chert seams are visible in the limestone

bluff opposite the site, cobbles and fractured chert pieces

are common in the gravel bed of Leon Creek, and, most importantly,

chert was available on the site along a natural limestone

bench that was exposed in Paleoindian times. The chert present

along the bench ranged from pebbles to small boulders up

to 40 centimeters (about 16 inches) across. As chert goes,

the local material is not of a particularly high quality.

It is highly weathered (turning it white and eventually

soft and chalky), often fractured, and sometimes contains

internal masses of a harder chert that makes flint knapping

difficult. Most of it is white to gray in color. Despite

its uneven quality, the Pavo Real chert was used intensively

by the Paleoindian groups who camped at the site and less

intensively by later Archaic peoples.

The third factor is that the site is located

along a broad ecotone or zone of mixed plant and

animal communities sharing characteristics of the Edwards

Plateau (Balconian biotic province) to the north, the Blackland

Prairie (Texan biotic province) and the Gulf Coastal Plain

(Tamaulipan biotic province) to the south. North of the

site, the plateau is rocky, hilly, and has mostly thin soils.

The vegetation is drought-resistant oak-juniper savanna

on uplands and slopes with hardwood forests in the better-watered

canyons and valleys. Along perennial streams are found cypress,

pecan, willow, and other trees dependent upon abundant water.

Among the streams and rivers that form the Balcones Canyonlands,

Leon Creek is rather small and intermittent. Not far east

of the site is a narrow band of the Blackland Prairie, which

was originally dominated by tall grasses. South of the site,

is the expansive Gulf Coast Plain, which is covered mainly

in drought-resistant thorny scrub brush and grasses except

along streams.

In summary, the Pavo Real site was located

on a natural transportation corridor in a location that

provided prehistoric peoples with convenient access to the

basic necessities of hunting and gathering life: water,

tool-making materials (chert and wood), plants and animals.

But don't get the wrong idea—Pavo Real was not a particularly

idyllic or favorable spot, it was just in a general location

that had lots of things going for it. There are (or were)

dozens of other prehistoric sites located along this stretch

of Leon Creek, some of them were probably more-favored spots,

to judge by the relative quantities and densities of refuse.

Many major prehistoric occupation sites occur along the

Balcones Escarpment, especially at the major springs and

along the larger streams and rivers. At times of drought,

the Balcones Canyonlands may have served as critical resource

areas because of the permanent water and wealth and diversity

of other natural resources.

Investigations

When TxDOT archeologists began to investigate

Pavo Real, they thought it was a typical Archaic campsite,

as it indeed proved to be (in part). Archeologist Jerry

Henderson was placed in charge of the fieldwork assisted

by Glenn T. Goode and several other TxDOT archeologists.

Initial backhoe testing in late May 1979 revealed the presence

of several shallowly buried middens and deeper deposits

suspected to date to the Early Archaic (about 7,000-9,000

years ago). As the TxDOT work progressed, the Archaic deposits

at 41BX52 were found to include at least one well-developed

burned rock midden (Feature 4) as well as several smaller

middens, all located along the terrace edge nearest the

creek. A hearth field of undetermined extent occurred in

the vicinity of the annular (ring-shaped) midden, the only

area of the site where the Archaic deposits were sampled

reasonably well.

Following the backhoe trenching in May, 1979,

the TxDOT archeologists began hand excavations at Pavo Real

to examine the middens and dig below them in hopes of finding

an Early Archaic component. [Most burned rock middens date

to the Middle Archaic period (about 5,000-7,000 years ago)

or later. The lifeways of earlier Archaic peoples was very

poorly known in the late 1970s and was the subject of considerable

interest.] For most of the summer of 1979, the archeologists,

aided by local TxDOT workers opened up a series of small

excavation units, mostly 2-x-2 meter squares, in different

parts of the site. They concentrated most of their effort

in and around the site's largest burned rock midden (designated

Feature 4).

By mid-August time was running out; fieldwork

was scheduled to be completed before the end of August.

Thus far the site hadn't turned up much that was particularly

interesting or different from previously excavated sites.

It was a typical burned rock midden site dating mainly

to the Middle and Late Archaic periods with some evidence

of Early Archaic occupation. But preservation conditions

were poor—almost nothing was found except burned rocks,

dart points and other chipped stone tools, and lots of tool-making

debris. In a few cases some charcoal was found in some of

the hearths that might yield radiocarbon dates.

Friday August 17th would be the last day for

the local workers, and the Austin-based archeologists expected

to wrap things up the following week. It was apparent that

many of the excavation units could not be completed within

the remaining time. Then, unexpectedly, a Clovis point

was found on August 15th within what had previously

been considered an Early Archaic deposit (only 45 centimeters,

or 18 inches, beneath the surface). This find was potentially

important because Clovis sites were rare—was this an

isolated find?

The archeologists were given a several-week

extension to determine whether intact Paleoindian deposits

were present. By late September they had found a Folsom

point and other early artifacts and determined that an isolated

Paleoindian component was present, sandwiched between two

gravel lenses. A Gradall (a large precision-digging machine

often used in highway construction) was then brought in

to remove most of the remaining Archaic deposits north and

east of Feature 4. Despite continued pressure to hurry up

and finish the dig so that highway construction could proceed,

the dig was extended by several months to investigate the

Paleoindian materials.

The second half of the dig, from October,

1979, to January, 1980, concentrated exclusively on the

site's Paleoindian component, which rested in a sandy layer

between two gravel lenses. Henderson was still in charge

of the work, but additional experienced professional archeologists

were hired on to help. At the time, the archeologists thought

the early materials dated mainly to the Folsom period and

so they called the sandy layer the Folsom zone. To

investigate the zone, they laid out a series of 2-x-2-meter

squares that systematically covered most of the area (in

contrast to the spotty approach taken with the Archaic dig).

Instead of digging using mainly shovels, as was done with

the Archaic dig, they dug mainly with trowels and carefully

plotted the locations of many of the artifacts they found.

In addition to the archeological dig there

was also geological work done to try and understand how

the Paleoindian component formed. This mainly consisted

of using heavy machines to dig deep, but narrow, trenches

through various parts of the site followed by detailed geological

recording. Unfortunately, the geological work was not coordinated

with the archeological work, resulting in several missed

research opportunities. For example, the deposits identified

geologically as those most likely to show stratigraphic

separation between Clovis and Folsom occupations were not

targeted by the archeological excavations. Another missed

opportunity was the chance to effectively sample a deeply

buried deposit beneath the main Paleoindian deposit. Flint

flakes (tool-making debris) were found in a deep geological

test, but this was not followed up by excavation. These

materials could date to earliest Clovis times or possibly

even earlier.

One very far-sighted thing that did come from

the geological work was the taking of four soil monoliths.

Archeologist Grant Hall from the Center for Archaeological

Research at nearby UT-San Antonio lent his expertise in

this effort. Soil monoliths are columns of sediment that

were carved out of the walls of some of the trenches, solidified

with a plastic resin, wrapped in burlap, and then encased

in wooden boxes built around the columns. The accompanying

photographs show how this was done. Such samples provide

"witness columns" of intact sediments for future

studies. And, in fact, archeologists and soil scientists

20 years later were able to take samples from the archived

Pavo Real soil monoliths and apply sophisticated new analytical

techniques to study how the site formed and to date the

site's deposits.

After the Pavo Real dig ended in early 1980,

the materials were processed in TxDOT's archeological laboratory

and Jerry Henderson began initial analysis. Unfortunately,

other agency priorities intervened, personnel changed, and

the project remained uncompleted for two decades.

In 2000, archeologists from the Texas Archeological

Research Laboratory began to analyze the Pavo Real materials

under contract to TxDOT. Noted Paleoindian expert and geoarcheologist

Michael B. Collins directed the studies of the Paleoindian

materials. Pavo Real's Archaic materials were studied by

Steve Black, who had directed the excavation of another

Archaic burned rock midden site in northern Bexar County,

the Panther Springs Creek site, in 1979-1980 while the work

at Pavo Real was underway. Dale Hudler managed the project

and undertook a variety of special studies of projectile

points and other materials. Expert consultants were called

in to do other specialized studies, particularly those of

the soil monoliths. The work was completed in 2003, culminating

in a thorough scientific report and this web exhibit.

|

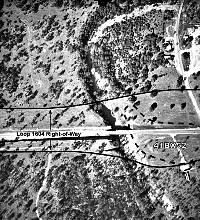

Aerial photograph showing site

vicinity as it appeared at the time of the 1979 excavations.

Note the sharp bend in Leon Creek just upstream (north)

of Pavo Real (41BX52).

Click images to enlarge

|

Archeologist Jerry Henderson during

the initial analysis phase in 1980. Unfortunately,

other priorities intervened before the analysis could

be completed and the site materials remained unstudied

for another 20 years.

|

View north from Pavo Real of the

Balcones Escarpment. The large limestone quarries

visible have provided building material for the growth

of San Antonio. Beyond the escarpment lies the Edwards

Plateau.

|

| |

Initial excavations underway on

south side of highway. Here the top of a "sheet"

midden, or thin burned rock accumulation, is being

exposed. Leon Creek is in the background.

|

|

FAQ: What is

a burned rock midden?

A burned rock midden (BRM) is basically

a refuse accumulation of fire-fractured cooking rocks

("burned rocks") that.... read

more>>

|

Two hearths uncovered in the Archaic

deposits at Pavo Real. The one in the background,

Feature 6, was a little over 4 feet across, while

the nearest one measured about 2.5 feet across. Such

small to medium-sized hearths are probably the heating

elements of small earth ovens.

|

The many excellent overhead pictures

of the Pavo Real were taken from the bucket of a "cherry-picker"

truck. Field director Jerry Henderson also served

as project photographer.

|

Geological trenching in progress

at Pavo Real in 1979. Geologist Chuck Johnson monitors

the progress.

|

Here one of the deeper soil columns

has been isolated to prepare it for being jacketed

and stabilized as a soil monolith.

|

|

Archeologist Grant Hall trims

the soil column before adding more boards.

|

Archeologists work to free the

soil monolith, now surrounded on three sides by boards,

from the excavation wall. Once free, a fourth board

will be added to create a protective box for the monolith.

|

|

Here is one of the soil monoliths

from Pavo Real, 20 years after it was boxed up and

stored. The darker soil at the top of the column is

that of the Archaic deposits. The Paleoindian layer

is just below the thick layer of gravel visible about

mid-way down.

|

|